Feelings, Wishes, and Necessity

Even when we are attentive to a situation and we feel some level of happiness, interest, and compassion about it, and some level of willingness to become involved, we need to respond sensitively and appropriately. Frequently, we need to decide between three choices: doing what we feel like doing, what we want to do, and what we need to do. Decisions involving someone else add the further choices between what the person wants and what he or she needs. Some or all these choices may coincide. Often, however, they differ. Choosing either what we want or feel like doing over what is needed, or what the other person wants over what he or she needs, is a form of insensitivity. When we make such a choice, we frequently feel guilty. This overreaction happens because we experience what we need to do dualistically as what we should do. On one side stands a defiant "me" and on the other the unsavory action that we should do, but are not doing. Usually, a moralistic judgment accompanies the dualistic appearance.

Deconstructing the decision-making process, by using images such as a balloon bursting, resolves any tension over the issue of "should." In place of what we should do, this process leaves what we need to do. Yet, we might not know what we need to do or what someone else needs. To find out, we may rely on the five types of deep awareness, knowledge, experience, intuition, discrimination, and trustworthy external sources of advice.

Even when we know what we need to do, we may neither want to do it, nor feel like doing it. We may still feel tension, even if the issue of "should" does not complicate the matter. Do we need to be insensitive to our wishes or feelings? Is it an overreaction to feel frustration and disappointment at needing to ignore either one or both of them?

The issue is complex. Four combinations may occur between what we want and what we feel like doing. Suppose, for example, we are overweight and we know that we need to diet.

- We may want to keep our diet, but not feel like doing so when our favorite cake is served for dessert.

- We may feel like sticking to our diet, but not want to do so when we have paid much money for a hotel room and a breakfast buffet is included.

- We may both feel like keeping to our diet and want to do so when people tell us how fat we have become.

- We may neither want to keep, nor feel like keeping our diet when we are aggravated about something and want to drown our annoyance by eating cake.

In each case, we may choose either to eat some cake or to exercise restraint. How do we make a sensitive decision that we do not later regret?

Reasons for Feeling Like Doing Something and Wanting to Do It

Understanding the mechanism behind feelings and wishes helps to alleviate tensions between the two and between either of them and necessity. When we understand why we feel like doing something and why we might want to do something different, we can evaluate these factors. Weighing them against the reasons for what we need to do, we can then come to a reasonable decision.

The abhidharma presentation of mental factors and karma suggests the following analysis. The deeper we probe, the more sensitive and honest we are to the myriad psychological factors involved in making difficult decisions in life. For easier comprehension, we shall use the relatively trivial example of eating to illustrate the complexity of the issue. Appreciating the depth that any analysis must go in order to be accurate helps us to be thorough in considering the choices available in more serious decisions, such as concerning an unhealthy relationship.

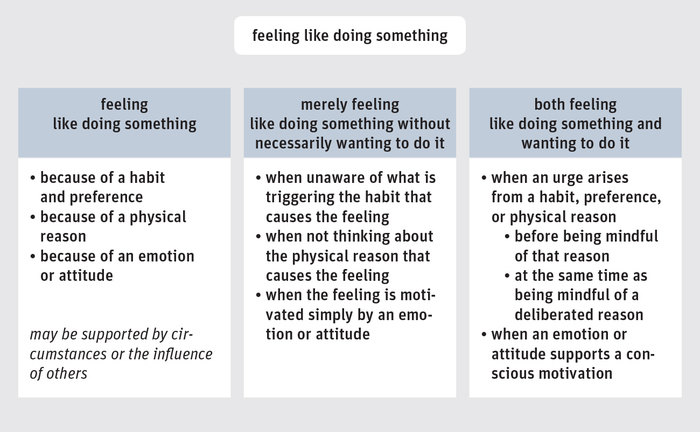

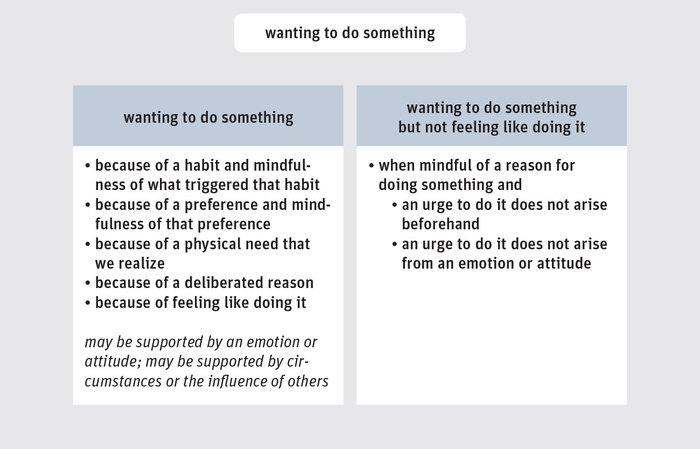

An urge is the mental factor that leads in the direction of a certain course of action. There are two types of urges: those that bring on the thought to do something and those that lead directly to doing it. Feeling like doing something brings on the former type of urge. Wanting to do it and deciding to do it accompanies the latter. Feeling like doing something arises when we are unaware of the reason. When we consciously feel motivated, we want to do it. Let us explore this distinction in depth.

Feeling like doing something may arise from a habit and preference, a physical reason, or the involuntary motivation of an emotion or attitude. For example, we may feel like eating something because of the habit and preference to eat at a certain time, because of hunger, or because of attachment to food. These three major causes may act either in combination with each other or independently. If we are in the habit of taking lunch at noon, we may feel like eating at that hour whether or not we are actually hungry and whether or not we are attached to food. On the other hand, when we are hungry, we feel like eating regardless of the time or our attachments. Further, when we are attached to food, we feel like eating at all times, no matter whether our stomach is empty.

When an urge to eat arises and we are unaware of the time or do not think about being hungry, we merely feel like eating. We do not necessarily want to eat. The same thing happens when the urge arises simply from attachment to food. Wanting to eat requires being conscious of a reason and feeling motivated by it.

We want to eat when we are mindful of what triggers our habit, of our preference, or of a physical reason for eating. For example, when we know it is noon or we think either about our preference for eating then or about being hungry, we want to eat. Similarly, we want to eat when we have a deliberated reason for doing so. For instance, we have no time later: if we are to eat at all, we must eat now. Awareness of feeling like doing something may also make us want to do it. Sometimes, we want to eat simply because we feel like eating. Although a psychological motivation for eating, such as attachment to food, is sufficient to make us feel like eating, it is insufficient to make us want to eat. We need another reason, such as it being lunchtime, and awareness of that reason. Attachment to food, however, may support our wish to eat.

Suppose an urge to eat arises from a habit, preference, or physical reason before we are mindful of that reason or it arises at the same time as we are mindful of a deliberated reason. In each case, we both feel and want to eat. For instance, we feel like eating because we are hungry. Subsequently, when we notice that it is noon or we realize that we have no time to eat later, we also want to eat. We may similarly experience both the feeling and the wish to eat when an involuntary psychological motivation supports a conscious, deliberated reason for eating. For example, we realize that we have no time to eat later and we are attached to food. We both want to eat and feel like eating despite it not being noon or our not being hungry.

On the other hand, if we are mindful of a reason for eating and an urge to eat does not arise either beforehand or from a psychological motivation, we want to eat but do not feel like doing so. For instance, although we realize that we have no time later, it is not our usual time to eat. We are not hungry and we are unattached to food. In this case, we want to eat, but do not feel like it.

Circumstances or the influence of others may support the arising of an urge to do something, whether we experience the urge as a feeling or a wish to do it. Without other causes, however, neither supporting factor is a sufficient cause for the urge to occur. For example, when food is on the table or when our friends are ordering at the restaurant, we may also feel like eating something and want to eat. Yet, not everyone responds in the same way. Without it being lunchtime, or without being either hungry or attached to food, or without having a deliberated reason, we will not feel like eating or want to eat even under these circumstances or in this company. What we decide to do is another matter.

Feeling like doing something and wanting to do it

Different combinations are possible between feeling like doing something and wanting to do something:

Choosing Between What We Want to Do and What We Feel Like Doing

Suppose we want to do one thing, but feel like doing the opposite. Let us leave aside for a moment the further complication of what we need to do. When we decide to do what we feel like doing rather than what we want to do, our habit, preference, physical need, emotions, attitude, or some combination of these factors, may be stronger than the deliberated motivation behind our wish or the emotional force behind that motivation. Our mindfulness of our reason for doing something may also be too weak or the circumstances or influence of others may be too overwhelming. For example, though we may want to lose weight, we may feel like eating a piece of cake. We choose to take a piece when our habit, hunger, greed, preference for a particular type of cake, our host's insistence, or some combination of these factors outweighs our vanity or mindfulness of how fat we are. When, in the same situation, we choose to do what we want rather than what we feel like doing, the strengths of the factors supporting each choice are reversed.

When we both want to do and feel like doing something, we choose not to do so when an extraneous motivation overrides all other considerations. For example, when we know that our host has specially baked the cake for us and would be hurt if we did not take a piece, we may decide to eat it despite wanting to keep to our diet and feeling like doing so.

Lastly, a deliberated motivation may cause us to do something though we neither want to nor feel like doing it. For instance, when we neither want to keep nor feel like keeping to our diet, we may refrain from eating anyway if we meditate on the disadvantages of being a slave to our greed. Here, our deliberated motivation of wanting to avoid these drawbacks outweighs any reason for wanting to break our diet, such as aggravation about work.

Doing What We Need to Do

We need to do something because it will benefit us, others, or both, or because of physical necessity or circumstances. For example, we may need to diet because losing weight will improve our self-esteem, will enable us to play sports with our children without losing our breath, or will improve our performance at work. We may also need to diet for health reasons or because we are traveling in an area where the food does not suit us. We do what we need to do when we are aware of the reasons for doing it, are convinced of their validity, feel motivated by them, and remain mindful of these three factors.

Someone may also force us to do what we need to do even if we do not see the need. For example, a strong-willed nurse or relative may bully us into eating when we are sick, even if we do not consciously wish to get well. This usually occurs because of physical or psychological weakness. We may be frightened of the person.

Unconscious motivations that derive from disturbing attitudes such as vanity may be behind our wanting to do something. They do not support, however, our needing to do it. They fuel, instead, our feeling that we should do it, such as vanity making us feel that we should go on a diet. On the other hand, certain attitudes, such as a sense of duty, family honor, or national pride, may make us feel either that we need to do something or that we should do it. This depends on whether we mix our outlook with confusion. Moreover, these attitudes are constructive, destructive, or neutral following from the ethical status of what we feel that we need or should do. Family honor may lead to helping the poor, vengeance killing, or living in a certain neighborhood.

At first, we may consciously have to motivate ourselves and exercise willpower to do what we need to do. Later, when we have built up new habits, we may spontaneously do what is needed and even feel like doing and want to do it.

Alienation from What We Want to Do or What We Feel Like Doing

Sometimes, we feel that we must suppress what we want to do or feel like doing and not "allow" ourselves to do it. We usually experience this as frustration. At other times, as a reward, we "allow" ourselves to do something that we both want to do and feel like doing, but in which we normally restrain ourselves from indulging. Then, when we actually do what we temporarily allow ourselves to do, we often feel irrational anxiety that someone will catch and punish us. We find it difficult to relax and enjoy what we are doing.

In addition, sometimes we feel that we have to force ourselves to do something that we know we should do, but that we neither want to do nor feel like doing. We often experience this with resentment. Moreover, often when we do what we feel like doing and not what we know we should do, we feel that we cannot control ourselves. Such experiences are often accompanied with feelings of guilt.

All such forms of alienation from our wishes, from our feelings, and from ourselves, stem from dualistic views. These are views of "me" and what I want to do, "me" and what I feel like doing, "me" and what I need to do, and "me" and what I actually do. In each case, the "me" and the choice of action seem to be concrete entities. Consequently, we experience the various seemingly concrete "me"s in conflict, fighting to control each other, with each "me" and what it wants, needs, does, or feels like doing bearing a concrete identity. When we identify with one of these "me"s that we imagine to be "bad," we feel guilty as the "bad" person who wants to do, feels like, or is doing something naughty. When we identify with one of these "me"s as the "good" person who must always be in control, we experience tension at having to be the police officer. We are never at ease with ourselves. To overcome these emotionally disturbing syndromes, we need the wisdom of nonduality.

Decision-Making

Decisions occur as the result of a complex interaction of mental factors without some concrete "me" in our head making the decision. This is true although the voice in our head worrying about which decision to take makes it appear as though a findable speaker is doing the worrying and making the choice. When a decision occurs, for instance to eat a piece of cake, all that happens is merely the seeing of the cake accompanied by the mental factors of discrimination and intention. These two mental factors arise from the interaction and comparative weights of:

- the habits, preferences, physical needs, emotions, and attitudes behind what we feel like doing,

- the conscious, deliberated, and nondeliberate motivations for what we want to do,

- the reasons behind what we need to do and our conscious motivation for doing it,

- any extraneous or deliberated motivations that might draw us to do something different from these three.

We experience our intention to eat, accompanied by the decisiveness of discrimination, as our will. Willpower then brings on the urge that directly leads us to act. We experience this urge as a decision.

Neurobiology similarly describes a decision from the physical viewpoint as the outcome of millions of brain cells firing. It agrees with Buddhism that no findable agent sits in our head making the decision. If we remain mindful of this common conclusion of both Buddhism and science, we stop viewing our decision-making dualistically. In this way, we avoid feelings of frustration, alienation, or guilt.

If we ask who made the decision to eat the cake, there is no denying that it was "me," not someone else. This conventional person "me," however, is not some findable agent in our head manipulating events. This "me" is like an illusion in that it seems concrete and findable, but in fact is not. Yet, it is not the same as an illusion. People make decisions; illusions do not.

Just because no concrete decision-maker sits in our head and our decisions arise dependently on causes and conditions, it does not follow that our choices are predetermined and inevitable. Predetermination implies that an all-powerful agent other than ourselves has independently decided for us. Neither we nor anyone for us, however, can make choices independently of the affecting factors. Furthermore, when we decide between what we want to do, what we feel like doing, and what we need to do, we subjectively experience making a choice. This is conventionally and existentially true. We do not know beforehand which decision we shall take. Nevertheless, no matter which decision we choose, all decisions arise from causes and conditions. Nothing happens arbitrarily without any reason. Therefore, all decisions are understandable. Moreover, we are accountable for them.

To make a sensitive decision, then, we need to check:

- what we feel like doing and why,

- what we want to do and why,

- what we need to do and why.

We then weigh the strengths of each, without becoming either overemotional or devoid of all feelings, and decide what to do.

Decisions are not always clear cut. Often we need to compromise. The first fact of life or "noble truth" that Buddha taught, however, is that life is difficult. We may feel sad at having to compromise our feelings or wishes, but there is no need to feel frustrated, angry, or alienated. As in accepting any unfortunate situation, we need to view our experience of sadness like a wave on the ocean of the mind. In this way, we avoid being battered. Our sadness will pass, like everything else.

Not Identifying with What We Want to Do or Feel Like Doing

The realization that no concrete "me" exists as a basis upon which to project a fixed identity allows us balanced sensitivity not only toward decision-making, but also toward ourselves. If we do not identify with the feelings or wishes that arise to do this or that, we do not judge ourselves as "bad" and feel guilty when the feelings or wishes are to do something bizarre or destructive. We see that urges and wishes to do things arise as the result of habit, physical needs, various forms of motivation, and so forth. An intention to act them out does not need also to accompany them. This realization allows us more sympathy and tolerance toward ourselves as we work to eliminate the causes for destructive urges to arise at all.

Not Knowing What We Want to Do or Feel Like Doing

Sometimes, when faced with a decision, we do not know what we want to do or feel like doing. When we are uneasy about this, we experience the phenomenon as alienation. We imagine we are "out of touch with ourselves." On the other hand, when we make decisions based purely on necessity, without considering our wishes or feelings, we may experience life as cold and mechanical. To overcome these problems we need to examine the possible causes for not knowing our feelings or wishes.

Feeling like doing something derives from an urge, which comes from habits, preferences, physical needs, emotions, attitudes, and so forth. While we are not liberated from our compelling habits, involuntary urges to do things constantly arise. Not all these urges have the same strength of intensity. When we experience not knowing what we feel like doing, we may merely be inattentive to a low-energy urge that is arising in that particular moment. To overcome the uneasiness that often accompanies the experience of not knowing what we feel like doing, we need to increase our sensitivity. We accomplish this by quieting our mind and being more attentive to the low-intensity urges that arise. We can then consider these feelings when deciding our course of action. In so doing, we experience our decision-making as a kinder and fairer process.

Feelings and Intuition

Intuition takes three major forms, each of which can also help us to make a decision. We may have an intuition about someone, such as that a woman is pregnant. Based on that, we may decide to help her carry a bundle. We may also have an intuition that something will happen, such as the doorbell will ring. Consequently, we postpone taking a bath. These first two forms of intuition are stronger than a suspicion. They have a quality of certainty to them.

An intuition may also be to do something, for instance to tell someone something about his or her behavior. Because of this, we may decide to speak to the person. A quality of certainty also accompanies this type of intuition. We intuitively know what to do; we do not merely have an opinion.

The English word "feeling" can be used in the context of all three types of intuition. We may intuitively feel that a woman is pregnant or intuitively feel that the doorbell will ring. We may also intuitively feel that we need to say something to someone. In each case, we do not merely feel these things; we feel them with certainty. In other words, intuitions are more compelling than feelings since they seem to derive from "inner wisdom." Moreover, intuitions often arise without an accompanying emotional tone. They may be intense or low-level, depending on our attention and mindfulness.

In deciding what to do, we also need to evaluate our intuitions. An intuition arises for unconscious reasons. Its source may be knowledge, innate deep awareness, or understanding built up from experience. However, what we take to be an intuitive feeling may also come from confusion or disturbing emotions. When we are paranoid, for example, our feeling that a journey will be dangerous may seem to us like an intuition of impending disaster. Intuition, then, may be a valid source of information or it may be incorrect. Although we need to consult intuition in coming to a decision, we also need care not to follow it blindly or impulsively.

Sometimes, we may feel like doing something, but intuition tells us something different. Here, too, we need care. One or the other may be correct, both may be partially correct, or both may be wrong. Intuition may be either an asset or a liability.

Compromising Our Preferences for Those of Others

When we are properly sensitive, we see what is troubling others and what they need. Their needs always take precedence over what they might say that they want. Sometimes, however, what they might want and need – for example, a show of physical affection or the space and time to be alone – is something that we find difficult to give. We may also not like giving it, not feel like giving it, or not want to give it. Moreover, because we do not like to receive the same ourselves, we may think that anyone who likes to receive it is immature or foolish.

Such a need or request from someone is different from asking for our time or money when we have none to spare. Although we may have certain psychological blocks, everyone is capable of giving someone a hug or of not bothering a person. To decide what to do, we need to evaluate our own and the other person's motivations and the possible outcome of any decision we might take. Although giving in to someone's needs or refusing them may make the person or us temporarily feel better, we need to do what is of long-term benefit for each of us.

Saying No

In deciding what to do, we need to be sensitive to our own needs as well as to those of others. Giving the person what he or she wants or needs – for instance, more of our time than we have available – may be damaging to our physical or emotional health. It may also restrict the time and energy we have for others. We need to say no sensitively, however, so that the person does not feel that a restriction is equivalent to a personal rejection. We also need to say no without guilt or fear of rejection.

One way to handle the situation is to give someone, particularly a friend or a relative, a set time each week exclusively devoted to him or her, for example breakfast each Saturday. We also make it clear that we have a weekly appointment afterwards, so that our time together is not open-ended. Setting limitations is the only realistic and practical way of leading our life. We cannot give everyone who wants to be with us equal time.

Prioritizing is difficult, especially when people are involved. Although family responsibilities, loyalty, and duty cannot be neglected, the main criteria are the other person's receptivity to our help and our effectiveness in benefiting him or her in some significant way. We also need to consider how much we gain or are drained by the encounter. This affects our general sense of well-being and our ability to interact more effectively with others. The teachings on karma suggest that, although everyone is ultimately equal, prioritizing also requires considering the benefit the other person and we can realistically give to others, now or later in life. This guideline applies to deciding not only how much time to spend with each person, but also how much energy to devote to ourselves.

Again, we need to be aware how our mind produces deceptive appearances of a seemingly concrete "me" who is overwhelmed with unfair demands and a seemingly concrete "you" inconsiderately making those demands. When we believe in this dualistic appearance and label ourselves and others in this confused fashion, we become tense and defensive. We have to ward others off with cunning excuses and, unless we are completely shameless, we naturally feel guilty. Deconstructing this dualistic appearance and trying to relate unself-consciously allow us to prioritize our time without feeling guilty. Changing our mental labels to "someone trying to help" and "people in need" is also helpful so long as we do not concretize the two.

On another level, our mind may produce a dualistic appearance of a seemingly concrete "me" who needs to be useful to justify our existence and a seemingly concrete "you" who can provide that elusive security by allowing us to serve. Fooled by this appearance, we may feel that if we say no to our friends, we will be rejected ourselves and thus lose any hope of gaining concrete existence from always catering to their demands.

Even if a friend does reject us, we need to focus on how life goes on. We are sad to lose contact with this person, but his or her disappointment, annoyance, or departure does not render us a worthless person. If Buddha himself was unable to please everyone, what do we expect of ourselves? Keeping these points in mind allows us to say no in a relaxed, sincere manner, without guilt or fear. It also allows us to understand and accept someone saying no to us, without feeling hurt.

Exercise 18: Making Sensitive Decisions

As a preliminary to making sensitive decisions, we need to divest decision-making from feelings of dualism. A convenient way to train is to work with an itch. We try to sit quietly without moving. When the inevitable itch arises, we try to notice how we both feel like scratching it and want to do so. Deciding not to scratch it, we try to observe how our mind automatically creates a dualistic appearance of a seemingly concrete tormented "me" and a seemingly concrete unbearable itch. Our mind tears the experience further apart by also creating the impression of a seemingly concrete controller "me" who will not give in to this annoying itch and of a seemingly concrete weak "me" who wants to surrender and needs to be controlled. If we identify with the seemingly concrete strong "me" and yet scratch the itch, we feel defeated by the weak "me." When this happens, we may experience the defeat with self-recrimination and thoughts that we should have been stronger. If we succeed in controlling the seemingly concrete weak "me," we may gloat with overbearing pride at how strong we are. In each case, the experience is disturbing.

We may deconstruct our experience by focusing now on the itch that we have decided not to scratch. It is merely a physical sensation that our tactile consciousness is producing and perceiving. Paying attention to it in this way, we try to notice that an intention accompanies our perception of the itch – namely, to endure the sensation and to resist ending it by scratching. This intention becomes more decisive when we pay attention to the itch as something impermanent that will eventually go away by itself. Analyzing in this way, we discover that no controller is directing the incident and restraining our hand from scratching. Refraining from scratching the itch, we try to focus on our experience as devoid of a seemingly concrete, solid "me."

Next, we consciously change our mind and decide to scratch the itch. Examining what occurs as we slowly scratch, we try to notice that the only change is the intention that accompanies our awareness of the itch. The intention is now to scratch it. This intention, fueled by the consciously motivated wish to stop experiencing this physical sensation, gives rise to an urge that immediately translates into the motion of our hand as we scratch. Again, no concrete boss stands behind the act, taking in information from the sensors in our skin and sending out orders to our hand. We try to focus for a minute on the fact that we are capable of making decisions without dualistic feelings.

An additional factor enabling us to make sensitive decisions is being relaxed with ourselves and accessing the natural talents of our mind and heart. Nervousness may make us indecisive and preconceptions may cloud our critical faculties. Therefore, as a further preliminary, we may repeat the practice without a mirror from the third phase of Exercise Nine. Relaxing our muscular tension, we use the "letting-go" and "writing-on-water" methods to quiet our mind of verbal thoughts, preconceptions, nonverbal judgments, projected roles, and expectations concerning ourselves and the decision we need to make. As in Exercise Fourteen, we then imagine any nervousness or emotional tension that might be left quieting down like a wave on the ocean when the wind has stopped. When we reach a calm, open state of mind and heart, free from tension, we rest for a minute or two with clarity.

Now we are ready to begin the main part of the exercise. We begin the first phase by focusing on a photo or on a thought of someone about whom we might have to make a difficult decision. Choosing, for example, someone with whom we are in an unhealthy or unsatisfactory relationship, we need to draw upon the various skills we have learned in the previous exercises.

First, we must decide whether something needs to be done. For this, we have to evaluate our impression of the situation. We begin by deconstructing any dualistic feelings we may still be unconsciously projecting. In other words, we try to stop seeing the relationship as a confrontation between a concrete "me" and a concrete "you." Imagining the balloon of that fantasy popping, we objectively check the facts, taking into account the other person's perspective and comments. Both sides undoubtedly have valid points. Placing the blame solely on one side is absurd. We may wish to consult an unbiased outside opinion. However, we need care not to lose our critical faculties and let bad counsel sway us.

Once we are certain of the facts, we need to determine with introspection:

- what we feel like doing,

- what our intuition says,

- what we want to do,

- what we need to do.

For example, we may feel like doing nothing. Yet, our intuitive feeling is that this will only make things worse. Moreover, we want to say something and we know that we need to do that.

We then evaluate the reasons behind each of the four. Making a list is helpful. Doing so may seem removed and analytical. Nevertheless, without some structure, we may simply take the easiest course of action – which is to do nothing – or torture ourselves with indecision.

- Feeling like doing something arises from habits, preferences, physical factors, and unconscious motivations. Circumstances and the influence of others may also contribute. Here, we may feel like doing nothing because of our habit of keeping quiet and our preference for avoiding confrontation. Examining ourselves deeper, we uncover fear of incurring the person's anger and also anxiety at the prospect of loneliness if he or she rejects us. Overwork and tiredness may also be contributing to our feeling of reticence.

- Intuition of what to do arises from knowledge, innate deep awareness, or understanding gained from experience. We intuitively know that keeping quiet will worsen the situation because we have seen this happen with others. Since what we take to be intuition may also come from a hidden attitude, we need to examine if this is the case. An unconscious drive to be in control may be reinforcing our intuition.

- A wish to do something arises from both conscious and unconscious motivations. Circumstances and the influence of others may also contribute. We want to say something because we can no longer tolerate the pain that the unhealthy relationship is causing us. Although we usually never acknowledge it, we may also feel oppressed. Moreover, several friends have been encouraging us to say something and the circumstances are right: we are spending the weekend together.

- Lastly, the need to do something comes from the benefits that both parties will derive. Even if the decision brings short-term pain, we need to aim for long-term benefits. Moreover, physical necessity and circumstances may also contribute to the need for action. Here, we know that we need to do something because the present situation is negatively affecting our work, our health, and our other relationships. Further, the relationship as it stands is unhealthy for the person too and for his or her relations with others. We love the person and wish him or her to be happy. Neither of us is happy now. Thus, our love and concern confirm the need. The person may feel hurt if we say something and we may feel sad afterwards. In the end, however, doing something now will benefit us both.

The first decision we need to take is whether to do anything at all. Having brought to the surface all the factors involved, we need to evaluate the positive and negative reasons for each choice. The main constructive reasons for action are the long-term benefits both of us will gain, our love for the person, and our honest concern for the welfare of both of us. Although our feeling of oppression may be a hypersensitive response, our intolerance of our present emotional pain is reasonable. Experience tells us that unless we do something it will only get worse. Our other friends' counsel corroborates this choice. The only negative factor behind doing something is our unconscious drive to be in control. To keep that in check, we need to listen carefully to what the other person has to say.

The advantage of saying nothing is that we avoid a potentially explosive confrontation, the other person's anger, and our possible future loneliness. The negative reasons for keeping quiet are our fears and insecurity. Since long-term benefits always outweigh short-term disadvantages, our anxiety is clearly a hypersensitive response. It is not a valid reason for inaction. The fact that we are overworked and tired suggests that perhaps we need to wait a short while, but we must do something soon. Weighing all factors, we see that the reasons for changing the relationship are more valid than the ones for doing nothing. We resolve to act.

Once we make up our mind like this and our motivation of love is clear, we are ready to decide what to do. The choices are either to try to restructure the relationship or to leave the person. To reach a conclusion, we need to adjust our ten mental factors and apply the five types of deep awareness. With a motivated urge, we focus on the person. With mirror-like awareness, we distinguish and pay attention to various aspects of his or her behavior. Using awareness of equalities and individualities, we further distinguish the patterns and yet respect the individuality of each instance. Pleasant contacting awareness and a feeling of happiness at the prospect of resolving the problem enhance our interest, mindfulness, and concentration. These, in turn, lead us to discriminate a course of action. We do this with accomplishing awareness. We then evaluate the wisdom and effectiveness of this choice with awareness of reality. Lastly, if the choice seems to be the most reasonable one, we set our intention to suggest it to the other person as we begin our discussion.

The decision-making process requires gentleness, warmth, and understanding, not the zeal of planning a battle. We must make sure that whatever we choose to propose is ethically pure – neither destructive nor dishonest to the feelings of the people involved.

To avoid insensitivity toward ourselves, we need to be clear about our limits. Yet, within those limits, we need to be prepared to say either yes or no about specific points as the discussion develops. We also need to choose an appropriate moment to broach the matter, when both of us will be receptive. Acting rashly may bring disastrous results. Most importantly, we need to approach the encounter without preconceptions. Maintaining awareness of reality allows us to give the person the room to change his or her ways, while realizing that no one changes instantly. It also allows us to remain open to his or her viewpoint and suggestions. If we find it helpful, we may rehearse possible things we will say and the steps we are willing to take ourselves. Nevertheless, as in settling any dispute, we need the flexibility not to follow a fixed agenda.

We try to imagine doing all this calmly and gently. Even if the other person becomes angry, hurt, or upset, we must resolve the problem. This requires courage and strength. Ridding ourselves of self-consciousness gives us that courage. When we speak and act nondualistically, we are no longer frightened or insecure. The abhidharma literature lists indecisiveness among the six most disturbing states of mind. When we waver or hesitate in making a decision about an unhealthy relationship, we lose time and energy in immature, painful psychological games. This prevents us from making progress in life.

If we later realize that we made the wrong decision, we need to accept our limited ability to know what is best. After all, we are not omniscient. Moreover, our decision was not the sole factor that affected what happened to the person or to us. Learning from experience, we can only try to use compassion and wisdom to go on from there.

During the second phase of the exercise, we sit in a circle with a group and focus on one of the members with whom we need to decide something. If we know any of them and have a dispute, we may work with that. If we have no quarrels or do not know anyone, we may deal with such issues as improving our relationship or establishing one. Approaching the challenge nondualistically and with warm concern, we try to assess the situation objectively and to evaluate what we feel, intuit, want, and need to do. We then try to use our ten mental factors and five types of deep awareness to decide a course of action and to resolve to do it.

We practice the third phase by directing our focus at ourselves, first in a mirror and then without one. Choosing a difficult decision we need to make about ourselves, we apply the same techniques. Useful topics include what are we going to do with our life, what work shall we do, where shall we live, whom shall we live with, shall we change jobs, when shall we retire and then what shall we do, and so forth. We need to apply the sensitivity skills we have gained through this program to help resolve the most difficult issues in life.

Outline of Exercise 18: Making Sensitive Decisions

Preliminaries

1. Divest decision-making from feelings of dualism

- Sit quietly without moving and, when the inevitable itch arises, note how you both feel like scratching it and want to do so

- Decide not to scratch it and observe how your mind automatically creates a dualistic appearance of a tormented "me" and an unbearable itch and then tears the experience further apart by also creating a controller "me" who will not give in to this annoying itch and a weak "me" who wants to surrender and needs to be controlled

- Deconstruct the experience by focusing on the itch that you have decided not to scratch and by noting that it is merely a physical sensation that your tactile consciousness is producing and perceiving

- Note that an intention accompanies your perception of the itch – namely, to endure the sensation and not to end it by scratching

- Observe that no controller is directing the incident and restraining your hand from scratching

- Refraining from scratching the itch, focus on the experience as devoid of a solid "me"

- Consciously change your mind and decide to scratch the itch

- Examine what occurs as you slowly scratch and note that the only change is the intention that accompanies awareness of the itch

- Focus on the fact that you are capable of making decisions without dualistic feelings

2. Relax to access the natural talents of your mind and heart

- Relax your muscular tension

- Quiet your mind of verbal thoughts, preconceptions, nonverbal judgments, projected roles, and expectations concerning yourself and the decision you need to make, by using the "letting-go" and "writing-on-water" methods

- Imagine any nervousness or emotional tension that might be left quieting down like a wave on the ocean when the wind has stopped

- Rest for a minute or two with clarity in a calm, open state of mind and heart, free from tension

Actual exercise

I. While focusing on a photo or on a thought of someone from your life about whom you need to make a difficult decision, such as someone with whom you have an unhealthy or unsatisfactory relationship

- Deconstruct any dualistic feelings you may be projecting onto the relationship as a confrontation between a concrete "me" and a concrete "you," by imagining the balloon of this fantasy popping

- Objectively check the facts, by taking into account your impression of the situation and the other person's perspective and comments

- Consult an unbiased outside opinion

- With introspection, determine:

- what you feel like doing

- what your intuition says

- what you want to do

- what you need to do

- List, on paper, the reasons behind what you feel like doing, such as

- Habits

- Preferences

- Physical factors

- Unconscious motivations

- Contributing circumstances

- Influence of others

- List the reasons behind what your intuition says:

- Knowledge

- Innate deep awareness or common sense

- Understanding gained from experience

- Hidden attitudes reinforcing your intuition

- List the reasons behind what you want to do:

- Conscious motivations

- Unconscious motivations

- Contributing circumstances

- Influence of others

- List the reasons behind what you need to do:

- Short-term benefits to each person

- Long-term benefits to each person

- Physical necessity

- Contributing circumstances

- To determine whether to do anything at all, evaluate the positive and negative reasons for acting and for not acting, paying particular attention to the short-term and long-term advantages and drawbacks of each choice:

- Weigh all the factors to determine which choice has more valid reasons backing it

- Resolve to follow that choice

- To decide what to do if the choice is to act, reaffirm your motivation, adjust your ten mental

factors, and apply the five types of deep awareness:

- With a motivated urge, focus on the person

- With mirror-like awareness, distinguish and pay attention to various aspects of his or her behavior

- With awareness of equalities and of individualities, distinguish the patterns and yet respect the individuality of each instance

- With pleasant contacting awareness and a feeling of happiness at the prospect of resolving the problem, enhance your interest, mindfulness, and concentration

- With accomplishing awareness, discriminate a course of action

- With awareness of reality, evaluate the wisdom and effectiveness of this choice, making sure that it is ethically pure – neither destructive nor dishonest to the feelings of the people involved

- If the choice seems to be the most reasonable one, set your intention to suggest it to the other person as you begin your discussion

- To avoid insensitivity toward yourself, be clear about your limits, yet be prepared to say either yes or no as the discussion develops

- Choose an appropriate moment to broach the matter, when both parties will be receptive

- Imagine approaching the encounter calmly and gently, without preconceptions

- Maintain awareness of reality throughout the discussion so as to give the person the room to change his or her ways, while realizing that no one changes instantly

- Remain open to his or her viewpoint and suggestions

II. While focusing on someone in person

1. Repeat the procedure while sitting in a circle with a group and focusing on one of the members with whom you need to decide something

- If you know any of them and have a dispute, work with that

- If you have no quarrels or do not know anyone, deal with such issues as improving your relationship or establishing one

III. While focusing on yourself

1. Repeat the procedure while looking in a mirror, to make a difficult decision concerning your life

2. Repeat the procedure without a mirror