General Classification

Habits (bag-chags, instinct) are the type of nonstatic dormant factor (bag-la nyal) that is neither a form of physical phenomenon nor a way of being aware of something. As such, they are non-congruent affecting variables (ldan-min ‘du-byed).

[See: Congruent and Non-Congruent Affecting Variables]

Moreover, “habit” is a general term for both tendencies (sa-bon, seed, legacies) and habits. Only the Mahayana tenet systems assert tendencies and habits as two distinct categories of habits. Here, we shall discuss only the Mahayana systems, and among the various Tibetan interpretations of them, only the Gelug. Moreover, within Gelug, we shall occasionally point out unique assertions from the Panchen and Jetsunpa textbook traditions.

Further, there are

- habits from karmic actions, which give rise to karmic ripenings,

- habits from experiences, that give rise to remembering, and

- habits that are included in the two sets of obscuration. Here, we shall discuss only the third type.

Distinctions According to Sets of Obscurations

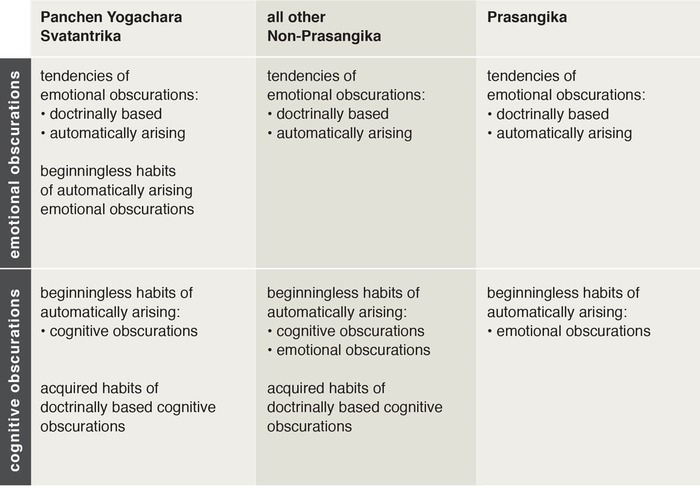

- Emotional obscurations (nyon-sgrib) – obscurations that are disturbing emotions and attitudes, and which prevent liberation – have both tendencies and habits.

- More precisely, among the emotional obscurations, doctrinally based ones (kun-brtags) have only tendencies; automatically arising ones (lhan-skyes) have both tendencies and habits. Doctrinally based obscurations derive from learning and accepting the incorrect assertions of a non-Buddhist Indian tenet system. Prasangika asserts that they may also derive from learning and accepting the assertions of a non-Prasangika Buddhist tenet system. Automatically arising obscurations come naturally, even to animals, without need to learn them.

- Tendencies of the emotional obscurations are included among the emotional obscurations.

- Except for Panchen Yogachara-Svatantrika, the habits of the automatically arising emotional obscurations are included among the cognitive obscurations. Panchen Yogachara-Svatantrika includes them among the emotional obscurations.

- Except for Prasangika, cognitive obscurations (shes-sgrib) – obscurations concerning all knowables and which prevent omniscience – have only habits. This is the case for both doctrinally based cognitive obscurations and automatically arising ones. These habits are included among the cognitive obscurations. In Prasangika, the cognitive obscurations are exclusively habits; they do not have habits.

- Except for Prasangika, the habits of the doctrinally based cognitive obscurations are acquired habits, and the habits of the automatically arising cognitive obscurations are beginningless habits. In Prasangika, the cognitive obscurations have no division into doctrinally based and automatically arising ones. This is because the cognitive obscurations consist solely of the beginningless habits of the automatically arising emotional obscurations.

Distinctions According to When They Produce Results

Until achieving a true stopping (‘gog-bden, true cessation) of them, tendencies may give rise to their results:

- occasionally

- or continuously.

Tendencies that give rise to their results occasionally may do so:

- with no beginning, but repeatedly reactivated at some time in only some lifetimes. Once reactivated, they give rise to their results only occasionally, until they temporarily stop giving rise to results at the end of that lifetime and are subsequently reactivated at some time during another lifetime.

- with a beginning in one specific lifetime, and then occasionally throughout that lifetime and all future lifetimes,

- with no beginning and only occasionally throughout each lifetime.

We shall call the first type “repeatedly reactivated occasional tendencies during some lives,” the second type “newly acquired occasional tendencies for all subsequent lives,” and the third type “beginningless occasional tendencies in all lives.”

Tendencies that give rise to their results continuously may do so:

- with no beginning, but repeatedly reactivated at some time in only some lifetimes. Once reactivated, they give rise to their results continuously, until they temporarily stop giving rise to results at the end of that lifetime and are subsequently reactivated at some time during another lifetime.

- continuously with no beginning.

We shall call the first type “repeatedly reactivated constant tendencies during some lives,” and the second type “beginningless constant tendencies for all lives.”

Until achieving a true stopping of them, habits give rise to their results continuously:

- with no beginning, but repeatedly reactivated at some time in only some lifetimes. Once reactivated, they give rise to their results continuously, until they temporarily stop giving rise to results at the end of that lifetime and are subsequently reactivated at some time during another lifetime.

- continuously with no beginning.

We shall call the first type “repeatedly reactivated constant habits during some lives,” and the second type “beginningless constant habits in all lives.”

Examples of the Different Types of Tendencies

For ease of discussion, we shall represent the tendencies of the disturbing emotions and attachment with the tendency of attachment.

Repeatedly Reactivated Occasional Tendencies during Some Lives

The tendency of doctrinally based attachment (‘dod-chags kun-brtags) gives rise to doctrinally based attachment. It begins to give rise to it only if and when, at some point in any lifetime, we learn and accept a non-Buddhist Indian tenet system assertion of a coarse impossible “soul” of a person (gang-zag-gi bdag rags-pa) and, consequently, develop attachment for that system. There is no first lifetime, however, in which the tendency is first laid. This is because all Indian tenet systems assert beginningless rebirth and thus their systems were never taught for a first time.

During the rest of the lifetime in which it has been reactivated, the tendency occasionally gives rise to doctrinally based attachment. It temporarily stops giving rise to attachment for the incorrect tenet system at the end of that lifetime. The tendency only resumes giving rise occasionally to this kind of attachment if and when, at some point in any other lifetime, it is reactivated and reinforced by learning and accepting once more an assertion of a coarse impossible “soul” of a person posited by a non-Buddhist Indian tenet system. At the end of that lifetime as well, it stops occasionally giving rise to doctrinally based attachment.

In Prasangika, this type of tendency also arises when we learn and accept a lower Buddhist tenet system assertion of truly established existence (bden-grub).

Newly Acquired Occasional Tendencies for All Subsequent Lives

Only Prasangika asserts this form of tendency.

In the case of tenet shravaka arhats (grub-mtha’ nyan-thos dgra-bcom-pa), the tendencies of automatically arising attachment give rise to subtle automatically arising attachment (‘dod-chags phra-mo). “Tenet shravaka arhats” are those who have gained nonconceptual cognition of only the lack of a self-sufficiently knowable “soul” of persons (gang-zag-gi rang-rkya thub-‘dzin-pa’i rdzas-yod-ki bdag-med) as asserted by one of the lower Buddhist tenet systems, but who lack nonconceptual cognition of the voidness of truly established existence as defined in Gelug Prasangika. These tendencies start to give rise to subtle automatically arising attachment occasionally during these practitioners’ first period of subsequent attainment (rjes-thob, post-meditation) after achieving tenet shravaka arhatship. Throughout the rest of that lifetime and each subsequent lifetime, they continue to give rise to subtle automatically arising attachment, and do so only occasionally, except during periods of total absorption (mnyam-bzhag) on the lack of a self-sufficiently knowable “soul” of persons as asserted by one of the lower Buddhist tenet systems. During such periods of absorption, they do not give rise to subtle automatically arising attachment at all.

The periodic recurrence of the subtle automatically arising attachment in periods other than total absorption on the lack of an impossible “soul” of persons as defined by the lower Buddhist tenet systems is in accord with the Prasangika assertion of nirvana with residue (lhag-bcas myang-‘das) and nirvana without residue (lhag-med myang-‘das, parinirvana).

- Subtle disturbing emotions are those that arise based only on grasping for truly established existence and on doctrinally based and automatically arising grasping for a self-sufficiently knowable “soul” of persons as asserted by Prasangika, without being also based on automatically arising grasping for a self-sufficiently knowable “soul” of persons as asserted by one of the lower Buddhist tenet systems.

- Note that the lower Buddhist tenet systems assert that grasping for a literally self-sufficiently knowable self is only automatically arising. One does not need to acquire it by learning and accepting the assertions of the self that are posited by a non-Buddhist tenet system.

- According to Prasangika, nirvana without residue (lhag-med myang-‘das) occurs during an arya’s total absorption on voidness, when there is no appearance of any impossible way of existing, or grasping for one. Nirvana with residue (lhag-bcas myang-‘das, parinirvana) occurs (1) during an arya’s nonconceptual total absorption on anything other than voidness, (2) during subsequent-attainment meditation, or (3) during periods in between meditation. During these times, there is appearance-making of impossible ways of existing, and grasping for one.

Beginningless Occasional Tendencies in All Lives

The tendency of automatically arising attachment (‘dod-chags lhan-skyes) gives rise to automatically arising attachment only occasionally, but with no beginning, throughout each lifetime.

Repeatedly Reactivated Constant Tendencies during Some Lives

The tendency of doctrinally based grasping for a coarse impossible “soul” of a person begins to give rise to this grasping only if and when, at some point in any lifetime, we learn and accept a non-Buddhist Indian tenet system assertion of a coarse impossible “soul” of a person. There is no lifetime, however, in which the tendency is first laid. During the rest of that lifetime, it continuously gives rise to doctrinally based grasping for a coarse impossible “soul” of a person. The rest of the description is the same as that for doctrinally based attachment.

In Prasangika, the same description pertains to doctrinally based grasping for truly established existence (bden-‘dzin kun-brtags).

Beginningless Constant Tendencies in All Lives

The tendency of automatically arising grasping for a subtle “soul” of a person (gang-zag-gi bdag-‘dzin phra-mo lhan-skyes) gives rise to automatically arising grasping for a subtle “soul” of a person continuously, with no beginning, throughout each lifetime. The only exception is during nonconceptual total absorption on the voidness of a subtle “soul” of a person, when there is not even the appearance-making of such an impossible “soul”.

In Prasangika, the same description pertains to the tendency of automatically arising grasping for truly established existence (bden-‘dzin lhan-skyes).

Examples of the Different Types of Habits

Repeatedly Reactivated Constant Habits during Some Lives

Only the non-Prasangika systems assert these.

The reactivated habit of doctrinally based grasping for an impossible “soul” of phenomena gives rise to doctrinally based grasping for an impossible “soul” of phenomena. It begins to give rise to this only if and when, at some point in any lifetime, we learn and accept a non-Buddhist Indian tenet system assertion of this type of impossible “soul”. There is no lifetime, however, in which the habit is first laid. During the rest of that lifetime, it continuously gives rise to this grasping, except during nonconceptual total absorption on the voidness of this impossible “soul”.

The reactivated habit temporarily stops giving rise this doctrinally based grasping at the end of that lifetime. The habit only resumes giving rise continuously to this grasping if and when, at some point in any other lifetime, it is again reactivated and reinforced by learning and accepting once more an assertion of an impossible “soul” of phenomena by a non-Buddhist Indian tenet system. At the end of that lifetime as well, it stops continuously giving rise to this grasping.

Beginningless Constant Habits for All Lives

In the non-Prasangika systems, the beginningless habits of automatically arising attachment gives rise continuously, with no beginning, to being bound in samsara. The only exception is a temporary one and that occurs during non-conceptual total absorption on the voidness of a subtle impossible “soul” of a person.

In the non-Prasangika systems, according to the Panchen textbook tradition, the beginningless habits of automatically arising grasping for a subtle impossible “soul” of a person gives rise continuously, with no beginning, both to being bound in samsara and to appearance-making of a subtle impossible “soul” of a person. According to the Jetsunpa textbook tradition, they also give rise to subliminal (bag-la nyal) automatically arising grasping for a subtle impossible “soul” of a person. The exceptions to this are the same as those concerning the beginningless constant habits of automatically arising attachment.

In all tenet systems, the beginningless habits of automatically arising grasping for an impossible “soul” of all phenomena give rise continuously, with no beginning, to appearance-making of an impossible “soul” of all phenomena, except during non-conceptual total absorption on the voidness of such a “soul”. This appearance-making is dualistic in the sense that the manner of appearance (snang-tshul) of how all phenomena exist is other than the manner in which they abide (gnas-tshul), i.e. the manner in which they actually exist. These beginningless constant habits also have a deception-causing facet from dualistic appearance-making (gnyis-snang-gi 'khrul-cha). This facet continuously, with no beginning, functions as the cause preventing the simultaneous cognition of the two truths of anything.

In the Prasangika system, the beginningless constant habits of automatically arising attachment function as the circumstance continuously supporting the “lack of clarity” (gsal-ba med-pa) of the mental continuum on which they are imputed. In this context, “lack of clarity” means the inability of the mental continuum to give rise simultaneously to the two truths of anything.