The Political and Religious Situation in Kashmir

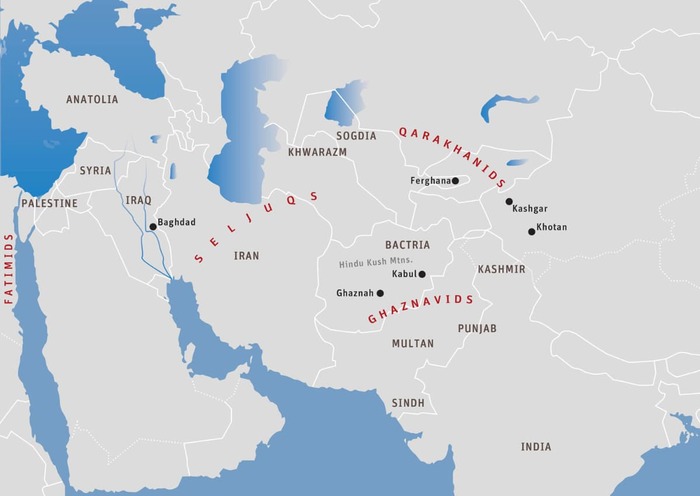

From 1028 until the end of the First Lohara Dynasty in 1101, Kashmir underwent a steady decline in economic prosperity. Consequently, the Buddhist monasteries suffered from minimal financial support. Furthermore, cut off by Ghaznavid territory from easy access to the great Buddhist monastic universities of the central part of northern India, the standards at the Kashmiri monasteries gradually declined. The last king of this dynasty, Harsha (r. 1089 – 1101), instituted yet another religious persecution, this time razing both Hindu temples as well as Buddhist monasteries.

During the Second Lohara Dynasty (1101 – 1171), and especially during the reign of King Jayasimha (r. 1128 – 1149), both religions recovered once more with royal support. However, the economic situation of the kingdom as a whole declined even further, continuing through the subsequent succession of Hindu rulers as well (1171 – 1320). Although the monasteries were impoverished, Buddhist activity flourished until at least the fourteenth century, with teachers and translators periodically visiting Tibet. Yet, despite Kashmir’s weakness for more than three centuries, neither the Ghaznavids nor their Muslim successors in India sought to conquer it until 1337. This is further indication that the Islamic rulers were more interested in gaining riches than converts from the Buddhist monasteries. If the latter were poor, they left them alone.

Seljuq Expansion and Religious Policy

Meanwhile, the Seljuqs expanded their empire westward, conquering the Byzantines in 1071. The Seljuq sultan, Malikshah (r. 1072 – 1092), imposed his overlordship upon the Qarakhanids in Ferghana, northern West Turkistan, Kashgar, and Khotan. Under the influence of his minister, Nizamulmulk, the Seljuqs built religious schools (madrasah) in Baghdad and throughout Central Asia. Although madrasahs had first arisen in ninth century northeastern Iran, devoted to purely theological study, these new madrasahs were oriented toward supplying a civil bureaucracy for the Seljuqs that was well educated in Islam. The Seljuqs had a very pragmatic approach to religion.

Having opened Anatolia to Turkic settlement, the Seljuqs went on to take Palestine as well. The Byzantines appealed to Pope Urban II in 1096, who declared the First Crusade to reunite the Western and Eastern Roman Empires and win back the Holy Lands from the “infidels.” The Seljuqs, however, were by no means anti-Christs. They did not, for example, eradicate Nestorian Christianity from Central Asia.

Nor were the Seljuks particularly anti-Buddhist. Had they been, they would have either led or backed their Qarakhanid vassals in a holy war against the Tanguts, Qocho Uighurs, and Ngari Tibetans, all of whom were strongly Buddhist and militarily weak. On the contrary, during their rule of Baghdad, the Seljuqs allowed al-Shahrastani (1076 – 1153) to publish there his Kitab al-Milal wa Nihal – a philosophical text in Arabic containing an account of the Buddhist tenets and, like al-Biruni, referring to Buddha as a Prophet.

The Nizari Order of Assassins

The extremely negative image the European and Byzantine Christians had of the Seljuqs and Islam in general was partially due to their faulty identification of all of Islam with the Nizari branch of the Ismailis, known to the crusaders as the “Order of Assassins.” Starting in approximately 1090, the Nizaris led a terrorist revolt throughout Iran, Iraq, and Syria, with youths intoxicated on hashish being sent to assassinate military and political leaders. They wished to prepare the world for their leader, Nizar, to become not only caliph and imam, but Mahdi, the final prophet who would lead the Islamic world in a millenarian war against the forces of evil.

Over the next decades, the Seljuqs and Fatimids launched holy wars against the Nizaris, massacring them in large numbers. The Nizari movement eventually lost all popular support. These holy wars also had a devastating effect on the Seljuqs and, in 1118, the Seljuq Empire split into several autonomous sections.

Meanwhile, the Ghaznavids continued to weaken in power. They lacked the human resources to rule even their diminished kingdom. The Qarakhanids also declined in power. Consequently, the Ghaznavids and Qarakhanids were forced to become tributary states to the autonomous Seljuq province in Sogdia and northeastern Iran.