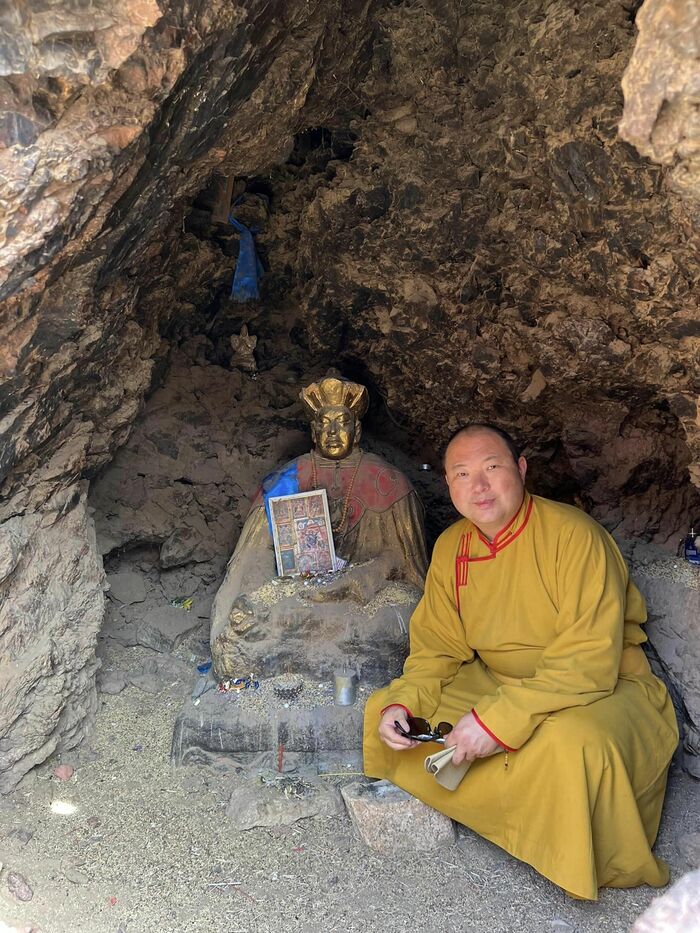

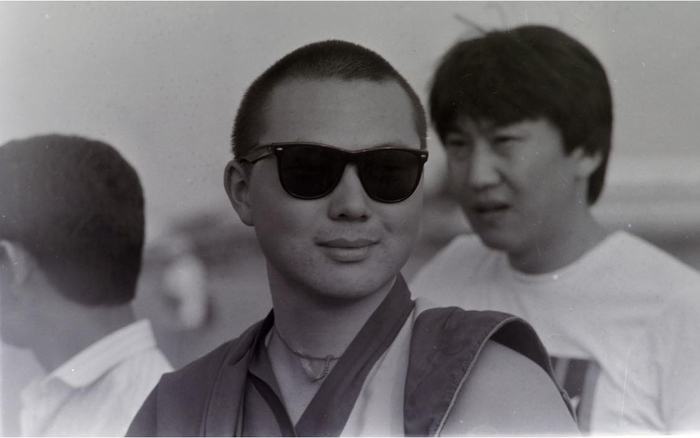

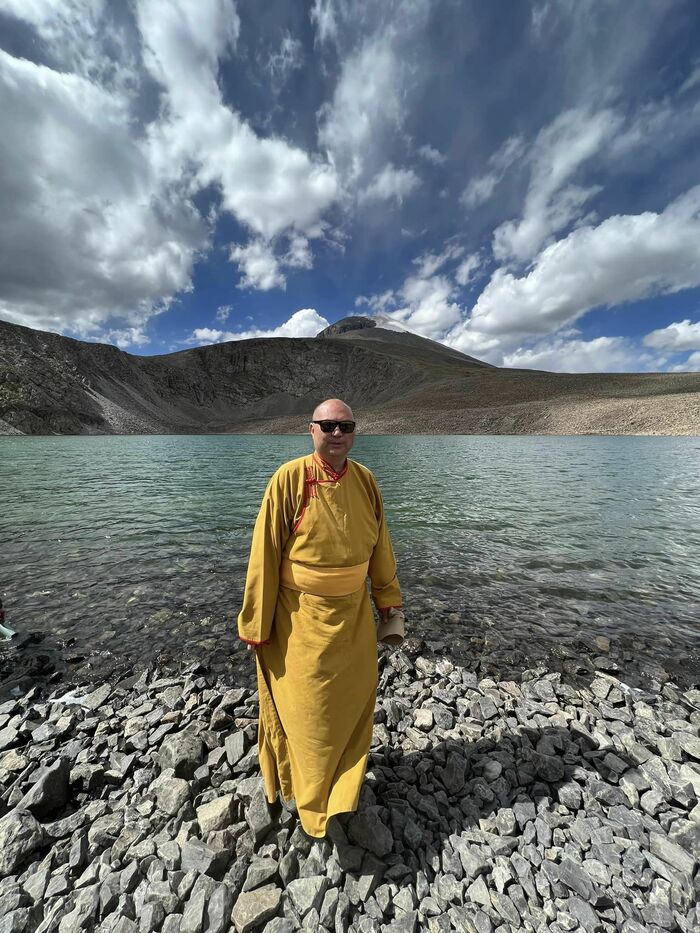

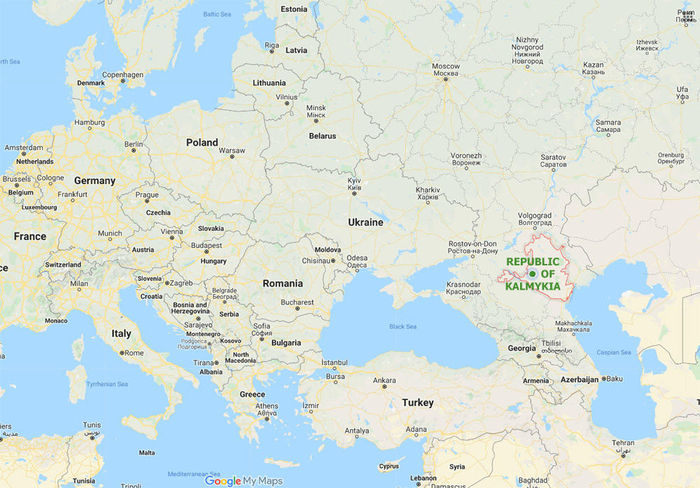

This interview with Telo Tulku Rinpoche is a captivating exploration into the life and contributions of a remarkable spiritual leader, a man who until very recently was the Shadjin Lama – the Head Lama of Kalmykia. Born in the USA in 1972 as Erdne Ombadykow, Telo Tulku Rinpoche would go on to play a pivotal role in the revival of Buddhism in Kalmykia, Buryatia, Tuva and Mongolia, inspiring countless individuals along the way.

Our conversation begins by delving into Rinpoche's tireless efforts to reintroduce Buddhism to these regions, which had suffered under decades of Soviet repression. With unwavering dedication, Rinpoche strived to restore the ancient teachings and traditions, guiding the Kalmyk, Buryat, Tuvan and Mongolian people back to their spiritual roots.

However, in 2022, amidst his noble pursuits, Rinpoche faced a great personal and spiritual challenge. His open condemnation of Russia’s war on Ukraine, driven by his unwavering commitment to nonviolence and compassion, led to the loss of his position as the spiritual head of the Kalmyk people. It was a profound moment of sacrifice as he stood by his principles in the face of adversity, knowing that his actions were driven by a genuine desire for peace and harmony. He now spends his time between the USA and Mongolia.

In this poignant interview conducted in Moscow, Russia in 2018, Rinpoche illuminates the essence of being a true Buddhist, emphasizing that it transcends mere cultural heritage or the beliefs of one's parents. True Buddhism, he explains, lies in taking refuge in the Triple Gem – the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha – out of personal conviction and a genuine quest for enlightenment.

As the conversation unfolds, the topic of hope emerges as a vital thread weaving through Rinpoche's teachings and experiences. With profound insight, he expressed that hope is not merely wishful thinking, but a force that propels individuals toward positive change. He emphasized the importance of cultivating hope, for it is hope that fuels the courage and determination needed to overcome challenges and realize aspirations. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: At the teachings you give across the world, you often like to pose the question “Why are you a Buddhist?” to the audience. What’s the thinking behind this? And of course, is there a right or wrong answer?

Telo Tulku Rinpoche: Usually when I give a teaching or a talk among people who were born as Buddhists, the very first question I ask is, “Are you a Buddhist?” And the answer is always “Yes.” My second question is, “Why are you a Buddhist?”

And the answer I get is always the wrong answer, which is, “Because my parents are Buddhists, because my grandparents are Buddhists, therefore I am a Buddhist.” That is the completely wrong answer! So, I always follow up with the question, “Okay, let’s say your parents were thieves. Does that make you a thief? Let’s say your grandparents and your parents were thieves. Are you a thief also?” They get offended by that, and they say, “No, of course not, I’m a good person!”

However, when you ask a non-traditional Buddhist, someone from a non-Buddhist background, people who have adopted Buddhism as their religion or as their philosophy, they give the right answer. When I ask, “Are you a Buddhist?” the answer is “Yes, I’m a Buddhist.” “Why are you a Buddhist?” “Because I take refuge in the Three Jewels – the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha,” which is the right answer. Russians or those from non-Buddhist backgrounds, those who have adopted Buddhism, they give the right answer. And why is that? Because they’ve explored, they’ve studied, they’ve learned, and after fully investigating, after developing conviction, they adopted Buddhism.

And that is the right approach, versus the traditional Buddhists just saying, “I’m a Buddhist because my parents are.” They make it sound as though it is something genetic, which it’s not! And I always look at the traditional Buddhists and say, “Look, there’s something wrong here. We consider ourselves traditional Buddhists, and we make a big deal about it. But we don’t know anything about it. Whereas these people who have no relation to Buddhism, they give the right answer, and they know more, they studied more, they investigated, they’ve done deep research.

We have to study and learn a little bit more about what is part of our identity, what is part of our culture, what makes us a Kalmyk or a Buryat or a Tuvan. We organize lectures and different programs, seminars and workshops. We place great emphasis on inviting Buddhist scholars from different backgrounds, such as Dr. Alexander Berzin, Professor Robert Thurman, Tenzin Priyadarshi, Dr. Barry Kerzin, as well as many other geshes or tulkus, such as Kundeling Rinpoche, Jhado Rinpoche, Jetsun Dampa Rinpoche and so on. We invite different Buddhist scholars from different backgrounds, so people have a choice of the different styles, different methods, and different approaches.

You have many decades of experience in (re-)introducing and teaching Buddhism to Western as well as Eastern audiences. What is the most important attitude that Buddhist practitioners should have?

We should have the mindset to question the teachings. Buddha himself said, “Be critical, be open-minded, investigate, look into it.” Intellectual study is very critical when studying Buddhism, because just as Buddha explained, “Don’t follow my words simply out of faith and devotion, always investigate.”

There are a lot of things mentioned in the sutras. Do I believe in all of them? As a Buddhist, it would be non-traditional or not the right thing to say, “I don't believe in it.” But yes, there are some moments that I have doubts. I wouldn’t say that I don’t believe, but I do have some doubt. But for the major part, I have no doubt, no question whatsoever.

We should not follow Buddhism just because it says so in the Kangyur and Tengyur. It’s there, it’s preserved for us to actually study, not to just be put on the bookshelves and remain there as a collection. It is there for us to read, study, investigate and question, and through questioning, we can fully develop our understanding.

Rituals hold significant importance across the various Buddhist cultures of the world. Some people perform rituals for self-transformation, some as a wish-fulfilling exercise. Do rituals work, and what exactly is their purpose?

I think in every culture, not only Buddhist, rituals play a very important role. Of course, to a certain extent, rituals are important, but what is most important is the mindset and the motivation of the people both carrying out the rituals, as well as those participating in them.

I like to give a very realistic explanation. If becoming rich is as simple as performing a ritual, then every Kalmyk would have become a millionaire by now. Because since the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union until today, we have been performing many different rituals, saying, “May all sentient beings be happy, may all sentient beings be free from all forms of suffering, may they have a good and healthy life, may their wealth increase, may their spiritual wealth increase, may their material wealth increase as well.”

We have performed many rituals. But have all of those wishes been achieved or not? From the people who are performing them, from the people who are participating, from the people who are just simply in the presence of these rituals, there has to be a collective effort. And through collective effort, I truly believe that many things are achievable. But it’s not simply through one individual performing a fancy ritual. There always has to be a very strong foundation. And the foundation should always be the right motivation and the right intention.

So, what is the key thing in rituals? The key thing is to change as an individual, to become more warm-hearted, more happy, more compassionate, more loving. Therefore, if performing these rituals is going to make you more compassionate, more loving, more kind, then why not? But still, there always must be that strong foundation accompanying it, which is right intention and right motivation.

You took on an immense task as the spiritual head of the Kalmyk Buddhists, working to rebuild the different elements of the Buddhist religion throughout Russia following devastating destruction and oppression of the religion. How did you find the inner strength to take on such a task?

I am very optimistic. If you look at the global situation right now, it’s not only Russia that is going through a difficult time, it’s the whole world. We have to be optimistic; we should never give up hope. Once we give up hope, then nothing can be achieved, nothing can be developed, whether spiritually or materially. Without hope, the things that we want to achieve in life, the things that we want to rebuild and further develop cannot be achieved. I think hope is the main driver for everyone, whether they are religious or non-religious.

Of course, we may have ten goals. Will all ten of those goals be achieved? That is always questionable. But even achieving just one or two goals out of the ten is usually through being optimistic, hopeful, and very positive. I think we have been able to prove this to people. Throughout the 90s, Russia went through a very difficult period in terms of political challenges, economic challenges, and many other social challenges. Nevertheless, we remained hopeful, we remained optimistic.

Within the last 20 plus years, we were able to re-establish Buddhism as Kalmykia’s national identity, as their national culture, as their national religion. This couldn’t have been achieved without hope.

And never think that “I am nobody, I cannot change anything.” Every change begins with very small seeds. And I truly believe in that, and I encourage everybody who sees this message to be optimistic and not to give up hope. There is always a better tomorrow. And as they say in the West, “There’s a light at the end of the tunnel!”

When you arrived in Kalmykia, what was the situation on the ground like? Had there been any preservation of Buddhism during the Soviet period at all – externally in terms of temples and so on and internally in people’s hearts?

It was very difficult for Buddhists to maintain their faith during the Soviet Union. During the communist period, many temples, monasteries, and libraries were destroyed, and monks and well-learned scholars were assassinated, tortured, or arrested.

But inner belief and faith can never be taken away with violence. Because their faith was internal, people were able to preserve their faith, and communism was never able to destroy it.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Buddhists were able to express and revive Buddhism through their inner faith. But I wouldn’t say that faith was maintained in detail. It was maintained on a very superficial level, with not much information, because many of the books were destroyed, or many of the well-learned scholars who had the ability to give detailed explanations were no longer alive. So, if you asked an individual to give an explanation about Buddhism in detail, maybe they were not able to give a full description of what they believed in. Nevertheless, they believed in something, and through that faith and through that belief, Buddhists were able to preserve to a certain extent their identity, their culture, and their religion.

Can you tell us in more detail about the process of the revival of Buddhism in Kalmykia? What were your first steps to help re-establish Buddhism there?

The revival of Buddhism among the Kalmyk people was very spontaneous, and at the same time very fast-paced – also among all Russian people as well. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Buddhist revival opened many doors to people who, until then, lived as prisoners within their own country, with so many restrictions, including restrictions to practice, to learn, to perform rituals or even to read about the different and various religious traditions.

The revival gave an opportunity to explore not only their own religious beliefs, but also many other religious traditions as well. I would say that the period after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 90s was probably the most interesting period in Russian history, because people explored. It gave them the opportunity to explore not only different religions but different cultures, different languages, different traditions, different rituals, different cuisines. Through this exploration, they were able to better identify what they believed in, what their dislikes were and so on.

When I first became the Head Lama of the Kalmyk Republic, there were no learned scholars that were alive. One of the first tasks that we made was to gather a group of young students who were interested in Buddhism, who wanted to become monks. We sent them off to India to Buddhist monasteries, so they could get the proper training and get the experience of living among hundreds or even thousands of monks and leading a different lifestyle than they were used to. Over a period of time, once they completed their studies, they were able to come back to Russia and take the responsibility of helping me to reintroduce and rebuild Buddhism. I would say that progress has been successful to a certain point.

You were also pivotal in helping the revival of Buddhism in Mongolia. How did it compare to the efforts in Russia?

There’s a huge difference between the revival of Buddhism in Russia and in Mongolia because, in Mongolia, Buddhism was not completely destroyed. Of course, the majority of monasteries were destroyed, and the majority of the monastic communities were destroyed, yet to a certain extent, Buddhism was preserved. When the Vice President of the United States made a diplomatic visit to Mongolia in the 1940s, Mongolia’s government wanted to prove to the outside world that religious freedom existed, that Buddhism existed as part of Mongolian life. So a few monasteries were allowed to function and to remain open to the public, designed as a sign to show to the American Vice President, but after he left, the Mongolian government decided to keep those monasteries that way.

In Russia, and in Kalmykia as well as in Tuva, all the temples and monasteries were completely destroyed. Also, the majority of the Buddhist monasteries in Buryatia as well were destroyed. But also there, in Buryatia, a very small number of monasteries were able to function under the tight control of and observation from the communist government.

What was the biggest challenge you faced during the journey of reintroducing Buddhism to Russia and Mongolia?

I would say the most challenging part of reviving Buddhism in Russia and Mongolia is on a mental level. Because you are challenging a totalitarian-system mentality, a communist mentality, where the people grew up as atheists, as non-believers. To prove to people with this mindset that religion is important, that religion is not simply a faith but that it is also a science, it’s a philosophy, it’s a way of life, is a huge challenge. Of course, it takes time, the conversion or change of attitude does not happen overnight. It’s a very slow process.

Buddhism has a very realistic approach to life and to situations in general. Through logic and reasoning, and through a realistic approach, I think people were able to slowly understand and realize how pragmatic Buddhism is, and how it can be applied to their daily lives. Not necessarily as a religion, but simply as a philosophy and a science as well.

Buddhism has gained considerable popularity not only in traditionally Buddhist regions but also in non-Buddhist cultures in Russia and the West. Could you shed some light on what you believe attracts non-Buddhist audiences to Buddhism? What aspects or teachings of Buddhism do you think resonate with these individuals?

During the Soviet time, there were wonderful Buddhologists, Tibetologists and Mongolists who studied these various Buddhist traditions and topics. I think the interest in Buddhism among the non-traditional Buddhists was more on an academic or scholarly level, not as a faith system or belief system.

Now, there are people who follow Buddhism simply as a philosophy or as a science. What is Buddhist science? It is the science of the mind. Since 2017, Russian scientists – neurobiologists, neuroscientists as well as psychologists – have taken a very keen interest in Buddhism. I think this is due to Buddhism’s realistic approach. It attracts a lot of people.

Nowadays in the West, when the Dalai Lama gives a teaching, the stadium is sold out. Are all the people attending these meetings or lectures Buddhist? Probably not. Probably a very small percentage are practitioners or true Buddhists. The rest of them, they’re interested in the wisdom, they’re interested in the philosophy, they’re interested to learn more from the Dalai Lama. I think that particular mindset is the same here in Russia.

As you have traveled extensively around the world, you must have witnessed how Buddhism has been adapted and embraced in various Western countries. Could you share your observations on the differences you've noticed in the way Buddhism is practiced and integrated into Western cultures compared to its traditional roots?

My observation is that in the West they modify Buddhism to fit their mindset. When you modify it so much, you lose the true essence of the message or of the teaching itself. While modification is needed, it should not be to the extent that the true essence is completely wiped out. That’s very dangerous. On the other hand, the Tibetan way or approach is fully authentic, but the way it is presented to non-traditional audiences, in the West or in non-Buddhist countries, can be too traditional, to the point that people lose interest.

Russia plays a very important role because of its geographical location. We are like a bridge between the East and West. It’s not a fully Western mentality nor is it a fully Eastern mentality. Russia has been able to balance both mentalities and both cultures, so I think Russia plays a very important role in being able to understand Buddhism and being able to define Buddhism both in a more traditional and modern way.

Despite being surrounded by neighboring non-Buddhist regions, Kalmykia has managed to maintain strong relationships and foster dialogue with its neighbors. In your experience, Rinpoche, what do you believe is the key to achieving successful interreligious harmony? What factors contribute to fostering understanding and cooperation between different religious communities in a region like Kalmykia?

His Holiness Dalai Lama speaks about interreligious harmony or interreligious dialogue. I think it is very important for us to have this open communication, open dialogue. When I say “dialogue,” it doesn’t necessarily mean that we have to sit down officially, formally, and have some kind of a dialogue. The key methods in maintaining harmony and friendship are through human-to-human level dialogue, understanding, friendship, exchange of thoughts, exchange of ideas. Getting to know each other, getting to know each other’s different backgrounds, and getting to know them as individuals.

In Kalmykia, for example, in the “Interreligious Council,” Muslims, the Christian Orthodox and Buddhists are all represented. Of course, we have different views on religious traditions, different views on political issues, and different views on social issues as well. But nevertheless, we meet often. If we remained isolated from each other because the others had a different belief spiritually, politically, economically and socially, then there’s no way that we can develop and work together.

So, it is important for us to sit down together, have tea, have a basic conversation and exchange these different views. And through these sincere dialogues and communication, we have been able to achieve so much.

Kalmykia has no Buddhist neighbors. To the North, East, and West it is all Christian Orthodox, to the South we have the Muslims. We have been able to maintain stability, harmony, and friendship through open dialogue between people, between governments, between administrations – mainly between the religious leaders or the religious communities. I think we have set a good example to the people as well.

You just mentioned about the importance of human-to-human dialogue, and His Holiness the Dalai Lama often speaks about the importance of secular ethics to the survival of humanity as a whole. Could you explain this concept of secular ethics?

Yes, the Dalai Lama often speaks about secular ethics. Secularism is based on ancient Indian philosophy, where it speaks about having no barriers, not being based on any particular religious tradition or belonging to any ethnic group. Many other religious traditions don’t accept secularism, or they view the word “secular” as something anti-religious.

Of course, we need a clear explanation about what “secular ethics” means. The Dalai Lama’s explanation about secular ethics is not based on any religious tradition. Though he’s a Buddhist and a Buddhist leader, this particular approach or philosophy is not based on Buddhism. Instead, it is based on the simple human nature that we all possess, which is love, compassion, kindness, forgiveness, which actually every religious tradition promotes and teaches.

You have to give examples, or you have to be an example yourself to convince others what secular ethics or ethics mean. I was born in America, I grew up in India, and nowadays I live in Russia, and I often describe myself as, “Made in the USA, assembled in India, and distributed in Russia!” So, I understand the different backgrounds, and different mentalities, and different cultures. I’ve been able to understand and find the balance of sharing this experience with people. And I share this through logic, through reasoning, through experience, through stories in my life that have formed me, or changed me for the better. Through the wisdom that I have been able to use and apply in my life, whether as a tulku, as a father, as an individual, as a non-believer or as a traveller – in so many different ways. When I share these stories, they are not based on faith or religion, they are based on how we function as human beings.

Rinpoche, thank you so much for your time and your insight into Buddhism in Russia and the West!