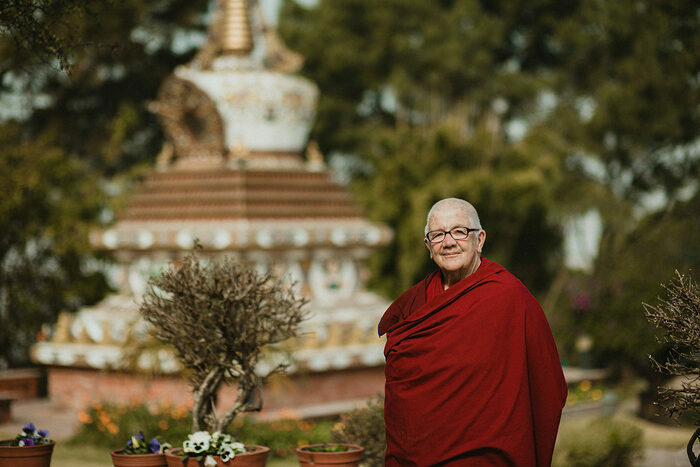

It is spring time in Kathmandu, Nepal, home to many ancient and sacred Buddhist sites. At this time of year, the pollution from the ever-growing city can be stifling, but Kopan Monastery, sitting atop a hill overlooking the valley, provides an oasis of peace away from the hustle and bustle. I’m here in the beautiful gardens waiting to meet someone I’ve heard many good things about, and whose book I read to prepare for the interview: Venerable Chönyi Taylor.

Venerable Chönyi Taylor, born Diana Taylor, is a Tibetan Buddhist nun, teacher and psychologist, who is known for her work bridging Western and Buddhist psychology, specifically in the field of addiction.

While studying for her degree in psychology in her native Melbourne, Australia, Dr. Taylor was also immersing herself in Buddhism under the direction of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, co-founders of Kopan Monastery and the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition. Following an impressive professional career in psychology and palliative care, she was ordained by His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1995. Now as a Buddhist nun, she continues her work in helping people with both Western psychology and Buddhist methods for attaining peace of mind.

Dr. Taylor is currently a lecturer and supervisor for the Australian Association of Buddhist Counsellors and Psychotherapists and is an honorary lecturer in Psychological Medicine at Sydney University. Her book on addiction, “Enough!: A Buddhist Approach to Finding Release from Addictive Patterns” combines cognitive therapies with Buddhist teachings and is suitable for self-study or as part of a guided program for anyone looking to break the cycle of addiction, whatever it might be.

Study Buddhism: You hold a PhD in psychology and you are an ordained nun, so you’ve got feet in both the professional and spiritual fields. For you, where do Buddhism and Western psychology meet?

Dr. Chönyi Taylor: When we're first studying Buddhism, we find that there are very practical teachings that can help us with the sorts of things that we experience here and now. Because, although we call it a religion, fundamentally it's a psychology.

Lama Yeshe said that Buddhism is the science of the mind because it's psychology and because humans are pretty much the same regardless of their cultural background. The reason why people get angry, get frightened, get depressed, are unhappy, or caught up in addictions all come from common processes in the mind.

By studying these processes, we learn how to utilize the mind, in order to change the mind. I think the Buddha was a very good psychologist. I once gave a talk to psychologists, saying the Buddha was the very first behavioral cognitive psychologist, because his techniques were the same. They're used in Buddhism, and they work because we're human beings. Whether it's CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), as we say in Western psychology, or the Buddhist variations on that, it doesn't matter, it still works. “What am I thinking about this? Is my thinking correct or not correct? How can I stop myself from overreacting? What can I put into place to stop it?” These are CBT questions, but they're also Buddhist questions.

That is so interesting. Despite being developed thousands of years apart and in completely different continents, the way you describe it makes it seem like these two systems are similar in many ways. In what ways, then, does Western psychology diverge with the Buddhist teachings on the mind?

Buddhism and Western psychology meet in terms of these behavioral patterns, which we want to change. Both of them have methods for dealing with this, but Buddhism goes one step ahead, where Western psychology doesn't follow. Buddhism says it's not only possible to change these patterns, but it is possible to get rid of them absolutely and entirely. You may still experience some pain if you break your leg, but you're not going to experience negative emotions due to the experience. You are not going to get angry or upset at the reason why you broke your leg.

So, the states of mind that go with pain become eliminated entirely, and because those states of mind are eliminated, we can develop more and more positive qualities. According to the teachings, we can go all the way and make the mind absolutely clear from any negative qualities. At that point we become a Buddha, which is rather nice to imagine!

So, there's a continuum, which is all spelled out in the texts, which can be a bit boring to study if you're not actually interested in the ways of getting to those higher stages. But if you stop and look at some of these lamas, particularly His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and ask, "How did he come to be the person that he is?" – his whole training as a child has been about compassion as well as wisdom and about how to develop compassion and use compassion. You see this in his eyes, and you hear this in his teachings if you ever have the opportunity to meet His Holiness, which I have had. He treats you as a very close, personal friend.

If we could do this with everybody it would make a huge difference, but in the West, compassion is not regarded as being of benefit so much. When we first studied animals, Darwin talked about animals as all savage, eating up other animals, and this is how they survive: it is the survival of the fittest. What was left out when Darwin wrote this was the kindness of animals. We didn't hear about the mother animal who feeds her babies. We didn't have the internet, where we can see amazing pictures of animals from different species looking after each other.

I actually have a slide which I use in my workshops: on one half of the slide there is a monkey who is rescuing a dog, and the dog is being held by the monkey. On the other side, there is a dog who is rescuing a monkey, the dog is holding the monkey in its jaws and taking it to safety. The photos are of different animals, but it just illustrates that compassion is part of the natural order, just as much as aggression is.

The need for compassion is only starting to become recognized in Western psychology. Particularly when it comes to addiction, there's more and more emphasis on the fact that people with addictions have often been in a state where they have not experienced compassion of any sort.

You just mentioned how Western psychology places lot of emphasis on working with the mind and less on developing a kind heart, while in Buddhism there is a strong focus on developing both wisdom and compassion. What is the role of the mind in the development of a kind heart and compassion?

The definition of the mind in Buddhism is that it is something which is clear and knowing.

"Clarity" of the mind means that all the thoughts and conceptions can be held by the mind, just as empty space can hold an object. "Knowing" of course is the awareness part of the mind. Within Buddhism the mind is different from the body. You can't examine the mind by doing MRI examinations. All that would reveal to you is that there's something happening in the brain, but it doesn't tell you what is happening. The only way to examine the mind is by looking at it.

As we look at our own mind and see the patterns, we start to see that other people have similar patterns too. Therefore, we become more understanding of other people as well. The more we look at our own mind and examine it, the more we understand our reactions such as when we get angry at someone in a situation such as when someone took our seats. We need to take the ego out of that situation, which is not easy to do in the middle of it: that's why we need to train. If I take the ego out of that, then I say,"OK, somebody is sitting in this chair. I thought I was going to be in this chair. She doesn't want to move, so therefore I have to find somewhere else to sit." It's simple.

There's no anger, it's just observing the situation and examining the reactions. You have to train to stop being depressed, stop being jealous, stop being upset about things. That's why we need to study the mind.

As an expert on both Western and Buddhist psychology, you wrote a book, “Enough!: A Buddhist Approach to Finding Release from Addictive Patterns,” a much loved practical guide to release us from the grip of negative habits and addictions that stop us from leading a meaningful life. Could you summarize what addiction actually is?

An addiction is simply a pattern, a habit. It comes from our ego which says, "I'm not going to be happy unless I get something." And the ego does this over and over again toward one thing. You can be addicted toward many things such as having a fast car, or you can be addicted toward having alcohol or drugs, but also you can be addicted to chocolate.

We call a habit an “addiction” when the result is harmful to ourselves. And when it's harmful to ourselves, it will be harmful to other people.

Could we say that addiction, in terms of Buddhist philosophy, is connected to karma?

Addiction can be very much related to karma both in the sense of being made easier by karma from the past, and also the addiction is creating the karma to repeat the same thing in the future.

Let's say in your previous lifetime you had a great fondness for chocolate, but your family was very poor. You rarely had chocolate, so it would be a big thing anytime you had the opportunity to have it. You'd be so happy as soon as you got it. This could lead you into your next lifetime already with the desire for chocolate. Then every time you have chocolate, it is deepening this desire. It is deepening the assumption that this will make you happy, and it is deepening the ego itself which says, “I have to be happy.”

This desire is, of course, a fundamental Buddhist concept and one of the causes of our dissatisfaction, so it’s easy to see how an extreme version of desire, such as addiction, could be destructive. How does addiction fit into the Buddhist teachings?

Buddhism is in fact about addiction. It is about undoing addictive patterns.

Of the three root afflictions, one is ignorance, which is obvious. One is anger, which is also obvious. The other one is usually translated as "attachment," but this attachment is not the same attachment as in Western psychology, such as in the case of the developer of attachment theory, John Bowlby. Rather, it is an addiction. A grasping, a needing, a “must have” type of thing.

You teach that changing compulsive behavior involves three tools: mindfulness, introspection, and equanimity. Can you tell us about these tools?

I started teaching courses balancing up my Western knowledge with my Buddhist knowledge, with the idea to come up with a step-by-step guide to find methods that will work.

The very first thing you do is to learn to breathe. The next step is finding ways to actually stop yourself in the middle of a pattern. That's not so easy. You stop yourself, you realize the thought pattern, and then you do the breathing. After that, you say, "Alright, why have I got this pattern?" This pattern is a habit, and we are trying to undo it. While we don’t worry about good habits, bad habits are a nuisance. There are of course neutral habits, like when you go from a manual car to an automatic car.

Actually, I drove a manual car for a long time and when I first tried an automatic, the first thing that happened was my foot kept looking for the clutch, which of course wasn't necessary. Even now, 15 years later, sometimes my foot goes looking for the clutch because I'm not thinking. Undoing that pattern is a matter of being reminded that we're falling into the pattern, and we can be reminded about this at earlier and earlier stages of falling into the pattern.

Apart from mindfulness and introspection, the third tool is equanimity. Equanimity essentially means having an even-minded emotional approach to things. So, if you are a chocolate addict and you see chocolate, as a chocolate addict automatically you would say “I want this!” and if somebody gets it before you do, you’d feel, “That's not fair!” In Western psychology it can be referred to as “catastrophizing,” which came from Jon Kabat-Zinn.

With equanimity we're just saying, "Well, there's chocolate here, I wonder if I could have some; no disaster if I can't.” Equanimity is part of learning that we don't have to be affected by this ego. So, when there's no ego, we're not grasping for the chocolate.

Talking of chocolate – which I love – I wouldn’t say I’m addicted. But at the same time, I do get cravings for it, especially if it’s after a long day and I’m watching TV. Most of us probably wouldn’t think of chocolate when it comes to addiction issues, but if we did want to overcome an addiction to chocolate, how might we go about it?

Lots of people have chocolate addiction! Imagine this: you know chocolate is stored up in the kitchen cupboard, and you keep a stash there, so that it's there when you want it. You've decided that you are going to give up chocolate but on this particular day, you've been busy working on something, you're tired, you want something for a quick hit, so you go into the kitchen, put your arm up to get the chocolate, and open the door with all the chocolates. And you suddenly remember during the process of opening the door that you've said, "No, I'm not going to do this." So then, you need to meditate on this moment of opening the door and what is happening there, going over and over this before opening the door, reminding yourself that “I'm not going to do it.”

After you've meditated on undoing the pattern of opening the kitchen door, you undo the pattern of reaching up. As soon as you go to reach up, you do a similar meditation. You go to reach up, you stop yourself before you get there, over and over again.

You might be able to go back to walking through the kitchen door, and from there you might be able to go back to finishing the work and realizing you're tired. So, you do these things at each stage, and that undoes the pattern which has been ingrained.

Once we've done that, we have to look at the emotions behind the pattern. Very often we get angry with ourselves, so that when we reach up to get the chocolate, we become very angry, "I'm stupid! Why did I do this? I didn't want to do this! I'm hopeless," and so on. And you feel worse, which means you want the chocolate even more.

When they’re so deeply ingrained, some of us might wonder what the point is of even trying to overcome addictions. What would you say to this?

If people or you are not being harmed, there's no problem. If you or others are being harmed, then there is a problem. So not every habit is an addiction. The problem comes when you do start to harm others. If you take the “ice” (crystal methamphetamine) epidemic, people take ice so that they can party on for the whole weekend without falling asleep. They don't even think that maybe they're going to become paranoid and kill somebody, or that it will leave them in a state of paralysis of some sort. They don't think about that.

We have to become aware of what addiction does and take responsibility for it. There are many people in society who say, "I don't have to take responsibility for other people." When we start looking at compassion, we realize that compassion is just as much a need for humans as aggression is, so we have to ask ourselves, “How am I developing this?"

You cannot, as a baby animal, grow up without a mother feeding you. It's just not possible. Somebody has given you this ability through the kindness of their heart. They've done this for you, and what do you do? You're just going around destroying everybody. What effect is that going to have? You're going to destroy other people: people will get angry, they will destroy people all over again, and the whole thing escalates. But if you practice kindness, then people will change their attitude toward you, and other people will change their attitude toward them, and that escalates.

Just by smiling at anybody you meet you can be an agent for change in this world. You don't have to be the President of the United States or the Prime Minister of Australia, where I come from, or any other bigwig you can think of. You can change this world simply by smiling at people.

If they smile back, we can be happy that they've been affected by this. If they don't smile back, maybe they've got some big issue they're working with. Nevertheless, the smile will soften that, rather than aggravate it. We don't have any choice but to recognize the power of compassion as being a major factor in building human relationships.

Nowadays, many of us are facing a rather new phenomenon: addiction to social media. Researchers have indicated that this can be more addictive than alcohol and drugs because of the ease of non-stop access to social media platforms through our phones. What are your thoughts on the many young people who feel a strong need to document their lives publicly and who take selfies every chance they get?

The addiction to social media is really, really funny, because teenagers have always wanted to know what they look like in the face of other people. They'll stand in front of a mirror for hours while getting dressed or look at a tiny pimple and wonder how to get rid of it, or whether their dress is at the right length for current fashion.

Therefore, I don't think this attitude is a property of social media. I think it's a property of the minds of the people who are using social media. They just now have a very powerful tool to do this. I don't know what these kids are going to do with all these selfies in the end! Put them on a hard drive somewhere, and then toss the hard drive into the ocean?!

They won't want to see them in another ten years. When books were first introduced, people were terribly worried that books would have a negative effect on the mind, that people wouldn't be able to remember anything, because they could read it in a book. People thought there might be things written in the book that they shouldn't read, and so on. You can dig through the internet and find quotes on that.

I think that the people who become addicted to screens are actually mainly addicted to something that keeps them out of society. If you think about it, if somebody spends a lot of time reading, we don't worry about a reading addiction. Actually, it can be an escape also, just as the internet can be an escape. I think the internet is a very, very powerful tool and can be used for a lot of good too.

The Buddhist teachings say that we all chase happiness but look for it in the wrong places. We get stuck on things that give us temporary pleasure rather than long term happiness, so does addiction arise from confusion about happiness?

Pleasure and happiness are very often mixed up together, and happiness is often used as a synonym for pleasure. Pleasure just means that I'm very hot, and somebody gives me an ice cream. It cools me down for a little while, I have pleasure in that. When I finish the ice cream, I'm hot again.

But there is a quality in happiness, which is deeper than that. Happiness is a state of mind, different from pleasure, which is with us all the time, without exception. That happiness is related to the joy of seeing other people being happy, or achieving what they want, or being released from their suffering in some way. That happiness also comes from recognizing the great kindness that we receive from other people, which we mostly don't recognize.

If I look at my robes, where did they come from? It's a combination of nylon and cotton, so the nylon would have come from a factory, and people would have had to build the factory, people would have had to pick the cotton, the cotton would have had to be spun, and all this had to be put together, and then it had to be dyed. There are countless people involved in just producing my robes. And without these people, I wouldn't have these robes.

Usually, we feel that we are alone, nobody cares about us. When we recognize this great kindness of others, then our hearts are filled with pleasure, because we know we're not alone, we realize we're part of an enormous system, where there is kindness.

And then there is the happiness, and this is probably the deepest form of happiness, that comes when we realize we don't need this ego that we thought we needed. The ego we assumed was inside us, which we have to save. We realize the whole thing is a myth. It doesn't exist. All its reactions, all its anger and jealousy and so on, become irrelevant.

We don't have those reactions anymore, and so we don't have negative feelings toward others anymore. So they're much less likely to have negative feelings toward us. But because we don't have those negative feelings toward others, we are happy non-stop. It just goes on, there's no reason to be unhappy.

In terms of getting away from a state of mind you don’t want to be in, many addictions have an impact on the brain and on the neurochemistry of the brain. So, if you're in a depressed state of mind, you might choose a drug that will increase serotonin, or you might choose a drug that will make you really hyped up, like amphetamines. This will then give you that feeling of being happy for a certain period of time, and often you need to take extra, because the brain gets habituated to the positive feeling.

A very common form of addiction is when you say, "I'll have a drink when I get home from work, it'll settle me down, I'll feel better." One may be OK, but sometimes that builds up and does become a problem. When this happens, we think that our happiness has come from the fact that we've got our supply of beer sitting there in the fridge. Then we'll be happy. But that happiness does not last. Happiness doesn't come from the alcohol or the sitting down and resting, even though the serotonin might be affected; the happiness comes from the state of mind. But because material things cannot change the mind, then the drugs themselves cannot do that. The only way we can change the mind is by observing how the mind works, by looking at the habits, and by changing the habits from negative habits, which is what addictions are, into positive habits of wisdom and compassion.

I imagine that addiction is often accompanied by a sense of shame. Can such an emotion push people to address their addiction, or does it hinder people from trying to get help?

The shame of addiction arises quite naturally when people become aware of the effect of their addiction on themselves and other people. Very often people who don't want to deal with their addiction say, "It doesn't matter, I don't have any shame about this," but inside they actually do. They're very ashamed of it.

With feelings of shame there is a very strong judgmental inner self, which says, "You've fallen into it all over again, you've been to Alcoholics Anonymous, you weren't going to drink again, three weeks later, here you are drinking." This very judgmental attitude aggravates the shame and makes it harder and deeper. Maybe this person has never had that sort of kindness and compassion that we talk about when we talk about mothers feeding their children.

But that's what needs to come in at this particular point. It's being kind to oneself – not kind to oneself in the sense of, "Oh it doesn't matter if I have this or not." But kind to oneself by not being judgmental. That sort of judgment is very harmful.

By studying all these negative emotions that we get, which cause us so much trouble, these are our cues into how our ego is controlling us. Sometimes when I've been teaching here in the monastery about these things, one of the things I do is say to people, "I want you to watch your mind when you go down to dinner. I want you to watch your mind every step of the way, how you are reacting to the other people around.

So, they get into a long queue and, on this particular day, let's say there are French fries. And everybody likes French fries, so the first people in the queue tend to take a large amount, and as you go down the queue, the pile of fries gets lower and lower and lower. What are the people at the end of the queue thinking? "How dare those people take more than their fair share, it's not fair! Why can't I get some?" All these sorts of questions arise from this ego.

This is why Buddhism can be very, very practical, when you understand how to apply it. Why do I get upset? Why do I yell as soon as I get out of my bedroom in the morning at everybody in the house? I'm already in a bad temper, I've already made assumptions about the day. It is my ego, which says that things are not going the way you want them to, and it's their fault. Not your fault, their fault always! So, until we stop and study the mind, we can't see how it functions.

Could you share a very short guided meditation for our readers to close this interview?

This is a very short meditation, just to stop for a moment.

Allow your mind to be calm.

That means just letting all that thinking go: all the worries you might have about addiction, all the things you think you ought to do, all the ways you feel that you're bad.

Bring in this calmness and the recognition that there is a lot of goodness in you as well.

When we become calm, the mind becomes clear. In that clarity, we can allow the goodness to arise. We can allow love to arise. Happiness for others. Forgiveness for ourselves. Just plain joy, that there is so much in this world which we can be joyful of.

Allowing the mind to settle down, to be clear, to recognize the goodness, and to allow the joy to be there, giving thanks that we've had this opportunity to do this together, that each moment of joyfulness is a moment where we change the world.

So, be happy!

Thank you so much for your time and for the fascinating insights into the addicted mind and how to overcome the force of our compulsive behavior.