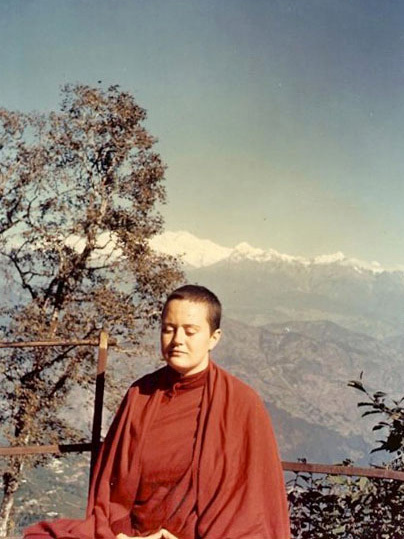

It’s late fall in Berlin, yet it’s still warm enough to sit outside and enjoy the fresh air and greenery. And what better place to do so than the garden of Bodhicharya Berlin, a beautiful Dharma center founded by Ringu Tulku (read his interview here!). Today, we are meeting with Lama Tsultrim Allione, the renowned Buddhist teacher, best-selling author, and founder of the Tara Mandala Retreat Center in Colorado.

Lama Tsultrim’s ground-breaking work in the integration of Western psychology and Eastern spiritual traditions has earned her international acclaim and recognition as a leading figure in contemporary Buddhist practice. It’s clear to see why – as we sat down to speak, I was struck by Lama Tsultrim's incredibly warm and open demeanor, as well as her infectious enthusiasm for the Dharma. Throughout our conversation, she shared insights and wisdom gained from many years of study, practice, and personal experience. Her deep understanding of Buddhist principles and practices, as well as her unique perspective on the role of women in Buddhism, made for a truly enlightening conversation.

In this interview, Lama Tsultrim shares her thoughts on a wide range of topics, from the ways in which we can work with our emotions to cultivate inner freedom, to the role of the feminine in spiritual practice, to Buddhist advice for dealing with deep grief. Her words are both insightful and inspiring, reminding us of the transformative power of Buddhist practice and the limitless potential for growth and transformation within each of us. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: Your first book, Women of Wisdom, explores the spiritual potential of the feminine through the lives of six Tibetan female mystics, and it was published a few years after the sudden death of your daughter, Chiara. What was the journey between your child’s passing and the writing of Women of Wisdom?

Tsultrim Allione: After Chiara died, I went through a huge crisis and really wondered about everything, about my practice, the choices I made, if it was a mistake to disrobe? Everything. Amongst those questions was where are the stories of women who may have had similar experiences to what I've had?

The Buddha's story wasn't helping me, because he left his wife and child in the middle of the night and went on his quest. I wasn't going to do that. And Milarepa's story wasn't helping me. He went to a cave, and I wasn't going to do that! I really began to feel that there must be some women's stories somewhere. Now, of course, it would seem obvious that we would need that, but at that time it wasn't an obvious thing, and I was the first one to really begin to ask those questions.

Do you think that the situation is better now? Or what can the Buddhist community do to address this imbalance?

First of all, there needs to be an admission of the fact that Tibetan Buddhism is patriarchal. Often, Buddhist teachers don't really want to admit it and say things like what they said to me when I was writing Women of Wisdom: "Basically, there's no problem. We have Yeshe Tsogyal, we have Machig Labdrön, we have Dechen Tsomo. And then…” Oh yeah, the list ran out!

Also, there's a lack of awareness of the capacity of women, which is now changing. We now have female khenpos and geshes, and finally women are becoming educated to the point where they can take those tests, and they are proving to be equally if not more capable of that level of study.

I think we need to get the full ordination back for women, and we need to have more women teachers, and we need to have the male lamas support that. Of course, not if they're not qualified, but not inwardly discarding them just because they're women, but to encourage and develop male and female disciples equally.

I think the men, the lamas, need to realize that there's a problem and take it on. It's like racism – until white people realize it's a problem for them, it's not really going to change.

In 2007, during a pilgrimage to sacred sites across Nepal and Tibet, you were recognized as an emanation of the Tibetan yogini Machig Labdrön. Can you tell us more about her life and accomplishments?

Machig Labdrön was a Tibetan woman who lived in the 11th century. She was a nun, and then she became a mother. So, she had that experience.

Then, she developed this practice called chöd, which is this template of feeding, not fighting. To me, it's not an accident that she was a woman, and that she came up with that method, because I think this idea of feeding and not fighting is a feminine tendency. To nurture, rather than the tendency to fight.

Her first teacher was actually a dzogchen master, a tertön (a revealer of treasure texts) named Drapa Ngönshe, who was a tertön for the Tibetan medical tantras. She actually learned dzogchen, which is interesting to me, because Machig Labdrön is usually associated with mahamudra, but her first teacher was dzogchen, and then she practiced the lineage of "zhi-byed sdug-bsngal," or "the pacification of suffering," that came from India through Āryadeva the Brahmin to Padampa Sanggye, who was Indian, but that was his Tibetan name.

Her teacher Sönam Lama was also a student of Padampa Sanggye, and the lineage is based on the teachings of Prajñāpāramitā. She called this lineage her father lineage.

Her mother lineage came through her own visions, visions of Tara and of the five dakinis and she wrote her own practices. The third lineage from Machig is called the lineage of experience, or "nyams," practices that came to her as meditation experiences.

She taught and gave those lineages to her sons: the father lineage from Padampa was given to her older son Gyalwa Döndrub, the mother lineage to her younger son Tönyön Samdrub, and the experience lineage to another male disciple. But she also had four important female disciples and she had a daughter, whom she also taught. Her lineage is actually our lineage, in that the terma cycle we practice at Tara Mandala comes through her daughter.

Machig Labdrön taught this practice of chöd. She founded a lineage in Tibet that dispersed after eight generations, when chöd went into the Gelug, Kagyu and Sakya traditions, and the Nyingma terma tradition. The main oral lineage that I’m familiar with is through the Third Karmapa in the Kagyu tradition, Rangjung Dorje, who wrote the first commentaries on chöd practice, and those have been passed down to us.

The term “chöd” literally means “to sever,” so what actually is chöd practice? Who are these practices for?

In the traditional practice, in the visualization, you’re offering your body to various different guests, chopping up your body and putting it into a skull cup, transforming it into nectar and then feeding a series of guests. Essentially, it's a practice of feeding, not fighting, that which assails us.

From that, I developed "Feeding Your Demons™," which you could say is a Western form of chöd. It's a five-step process to essentially do the same thing but using more Western modalities.

For somebody to really do chöd practice, it's challenging. The type of person who would practice the traditional chöd practice would be somebody already fairly mature in their practice. In a way, chöd practice is a way to test yourself, to test your development and your understanding, because traditionally you put yourself in what's called "nyen-sa," which means "difficult places" practicing this body offering. You actually should be afraid and work with that fear directly, and then you see how you do in those situations.

Can you tell us about your own experience of working with fear through chöd?

I did this retreat where you actually go to charnel grounds, and you sleep there all night. Or you go into strange caves and practice all night. You go to actual places that are meant to trigger fear. I had things happen to me in the process of it, where I was actually afraid.

Within that fear, which is always the attachment to the body, a tremendous potential power of liberation is created from that fundamental fear of, "Am I going to survive?" Letting that go and making offerings with the energy of that fear is very powerful. That's the traditional practice of chöd and the purpose of it: this confrontation process with fear, and then pushing through it. So, you meet it, and then you overcome it.

I am quite afraid of the dark, so I am not sure how I would handle going into dark caves at night! Your work in adapting transformative Buddhist practices for Western Buddhists resulted in the “Feeding Your Demons” method, which has become very popular. What are these demons exactly and what are we feeding them?

“Feeding Your Demons” has a five-step method in it for working with our demons, which are things like addiction, depression, and anxiety. “Feeding Your Demons” is a method that I developed when I realized that for myself and also for others, we were relating to the demons more as Buddhist concepts, rather than actual issues in our lives.

In this five-step process, you give form to, personify, ask questions to and then feed a demon, like a fear. It could be a fear of the dark, a fear of dying, it could be depression, it could also be a physical illness. With this method, you personify and then dialogue with it and essentially then dissolve your body and feed this demon.

Are there different types of demons?

There are different ways to classify demons, and Tibetans have a lot to say about demons! There are outer demons, inner demons, the demons of elation, and the demons of ego-clinging or arrogance.

Outer demons are anything that you perceive with your senses, that you react to. Historically or traditionally, they would say it's like a bear or a mountain lion, it's something outside that you react to with fear. It could be also more like a person that you're afraid of, or a situation.

Inner demons are demons that arise within the mind. They're not connected to a specific outer stimulation. Let's say you have depression that's not connected to grief, it's just within you, it's in your own mind. One of the ways in which these two are distinguished is that external demons are called demons that block, and the inner ones are demons that run on and on.

The demons that block mean that when you see that mountain lion, you freeze, you block, you grasp, you cling, and so your experience stops. It's like you're in an airplane

and there's turbulence: all of a sudden, your experience stops and you're in fear. The inner demon, the demon that runs on and on, is our minds, which just don't stop. So outer and inner demons are demons that block and demons that run on and on.

The third are the demons of elation or of aggrandizement. These are demons that can either be spiritually or materially aggrandizing. Things like fame, for a teacher, that's a potential demon. Or you have a special dream and then you think you're special. That's a more subtle and inner form of the demon that is generally associated with our spiritual development, clinging to that and enhancing the ego through that.

Then the fourth demon is ego-fixation or ego-clinging. In Tibetan it means arrogance. It's the very fundamental fixation that all the other demons develop from. I realized, after thinking about these demons for a while, that the reason this comes fourth and not first is that it takes that long to get to the root. Firstly, we can see the outer demon. If you're immature psychologically, you think the other person is the problem, the outside, right? And then you get maybe a little more insight, and you realize, "Oh no, it's in me." Then you keep going deeper and finally you get to this root. So those are Machig's four demons.

You often lead pilgrimages with your students. What is the significance of pilgrimage in Buddhism and what does pilgrimage mean for you?

Pilgrimage is going to a sacred place. The word for pilgrimage in Tibetan is "gnas-skor." "Gnas" means "power place," and I think this is a concept that maybe is a little difficult for us to understand in the West. At least for me, growing up in New Hampshire, we didn't have "gnas," we didn't have power places, we didn't have sacred places. A sacred place is often a certain confluence of natural things, like a cave or a river or a special place on the earth.

It's often also something that happened in that place. Pilgrimage is really going to these "gnas," these power places, and practicing and getting the blessings and the energy of that place.

Pilgrimage is meant to be, or traditionally was, difficult. It was hard. I remember when we were climbing Mount Kailash, and I was with Namkhai Norbu's sisters, and they were not riding on yaks even though they were old. They were saying, "No! It needs to be difficult, because purification is taking place with the difficulty."

Pilgrimage is an incredible practice because the places that you go to do really enhance your practice. For example, I had a specific experience at a cave of Guru Rinpoche, Padmasambhava, in Tibet, many years ago in 1992. Whenever I call Guru Rinpoche in my practice now, I go back to that cave and it's the portal that I reach him through. So, the places become kind of portals you can go back to in your practice and draw from.

You lost one of your daughters, Chiara, as well as your husband, David, who was your partner for 22 years. How did you deal with your grief? What advice do you have for us on coping with loss?

Grief is difficult. There's no two ways about it.

With both of them, it happened in the night, discovering they're dead the next day. That kind of death is very shocking. What helped me was to develop compassion. Before, somebody would say something like, "I lost my husband," and I would feel sad and say, "I'm sorry." But now I just get it. I know what that means, and it's in such a different way than I did before.

One important thing that helped me with my husband’s death and my daughter’s death is that I had the same thought of, "I'm not the only one." I thought of all the women who lose babies all the time in developing countries, after all that effort of pregnancy and birth. I was fortunate as a Western woman to not have that fear generally.

One of the things that helped me with David came out of a song that we sing at the end of practice, called "Taking Happiness and Sadness onto the Path," and it's basically a song that says, "Whatever happens, I'm happy, because I have the Dharma. If I die, I'm happy, because I can enter the dharmata at the moment of death." There's a line that says, "If I'm sad, I'm happy, because I can take the sadness of all onto myself and free them from sadness."

Then one night, about eight or ten months into the grief, we were singing that song and I thought, "Take the sadness of others onto yourself if you're sad”. But then I thought, "I can't do that, it's too much already, I'm barely surviving, I couldn't possibly take more." Every day, I felt like I was in a pressure cooker of grief. Then I thought, well, maybe you should try and just see what happens, so I tried to do a "tonglen" practice, which means taking the sadness of others and then giving back love and compassion. When I did that, I had the experience of imagining taking on the suffering of others who have lost their loved ones in worse situations too, and then giving back compassion.

My paradoxical experience was that I felt less oppressed by my grief. My heart opened, the pressure cooker top came off, and I began to feel some space around the grief, and also empathy for others. Somehow it was the release of the ego-fixation, which is there in grief also, into compassion, and that was a relief for me. That's something that I would recommend to someone experiencing grief.

In 1970, you became the first American woman to be ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun, but later you made the decision to disrobe and start a family. How does motherhood fit in with practicing Buddhism?

Balancing being a parent and being a practitioner is definitely a challenge.

It was a process that I went through: figuring out how I am going to be a parent and be a serious practitioner at the same time. I think it's partly bringing practice into the mundane. For example, when I was nursing my baby, I would visualize that I was nursing all beings and that this was an act of compassion. So, I could turn those hours of nursing into a compassion practice. I could work with the irritation that comes up as a parent, with patience. It's a perfect laboratory for emotions!

When I became a parent after being a nun, I had thought I had overcome all these emotions like jealousy, impatience, anger and so on. I realized I hadn't! And so it was very rich for me and humbling to realize I was just in very easy circumstances in my cave. And now I'm not getting enough sleep and have a mortgage.

The other thing is that it was important for me also to actually have time for meditation. So, I began to take off maybe a weekend or a day or an hour. I also kept a regular daily practice going most of the time when I was a mother. The kids would be crawling all over me, they'd be tearing down my shrine, but I did it. For me, that was important to keep that thread.

In your recent book Wisdom Rising: Journey into the Mandala of the Empowered Feminine, you teach about how to embody the enlightened, fierce power of the sacred feminine. How would you describe the sacred feminine and the sacred masculine and how they complement each other?

The sacred feminine is something we're just discovering what it is. It's been lost and oppressed for thousands of years. In terms of piecing together what the sacred feminine could be or is, the things that I see are emptiness, openness, an understanding of interconnection, interdependence, relationship.

We see that in the way that women function: they create relationships, within the family and within society. They are aware of how everybody's doing. Naturally as a mother you have to be aware. But the feminine also has sharp qualities: insight, the wisdom, the ability to cut through and see into the depth of reality. That's another aspect of the feminine.

The feminine, historically, has been associated with nature. So, when nature has been abused, so have women. Now we are at a moment on Earth, where we have a historical level of abuse of nature that's taken us really to the brink of disaster, and not only the brink but we're in it! And the abuse of women is also extreme, although there are some positive things happening.

So, the sacred feminine has many aspects. It does have this maternal and connecting compassionate aspect, it has also fierceness as a possible aspect, clarity, insight, and also the union of sexuality and spirituality. Another thing generally about the sacred feminine is that the spiritual is seen as imminent, meaning in the body. The masculine, historically, has seen the sacred as transcendent: nirvana, God, Allah. That it's somewhere out there, up there. The masculine sacred has been portrayed in that way, creating cultures where women and nature have been considered as obstacles to that transcendent ideal.

We see this in Buddhism too, the Buddha leaving his wife, leaving his child, and then wanting to get to nirvana. What’s interesting to me about Vajrayana Buddhism is there was a shift at that time into being in the body and into the idea of the world as sacred, the body as sacred. It's not any longer a decaying, disgusting representation of impermanence.

The body is the mandala, the body is the deity in Vajrayana. Therefore, it's probably not by coincidence that in the Vajrayana we have the presence of the feminine and women teachers. We don't know exactly the sources of Vajrayana, but it seems to have some roots in Shaktism, which is the worship of the sacred feminine, and also the Shaivite tradition.

The sacred feminine in the Tibetan teachings is "shes-rab," or wisdom, and the sacred masculine is "thabs," which is skillful means. The sacred masculine is that ability to manifest out of emptiness in a skillful way. I certainly saw this in my own life with my husband David. I had the vision of Tara Mandala Center in Colorado, and I was always having visions, and then he made it happen. He was the one making it happen. I think that's a capacity of the masculine. I think the sacred masculine also has the quality of protector, being able to protect the family but also really to think about protecting our world and doing that in a kind way. The masculine is also associated with compassion, because the feminine is emptiness in that the actual way that emptiness expresses itself is in compassion, and that's the masculine.

Lama Tsultrim, thank you so much for sharing with us your deep insight into Buddhism and its practices that allow us to transform our lives!