If you’ve ever been to Thailand and been given an address to find, it takes almost a miracle to make sense of it – at least for non-locals! It’s also hot – especially for someone more accustomed to northern climes, and even more so when carrying heavy filming equipment. I’m in Bangkok roaming down bustling alleys looking for a house, and thanks to modern technology, I manage to make it on time.

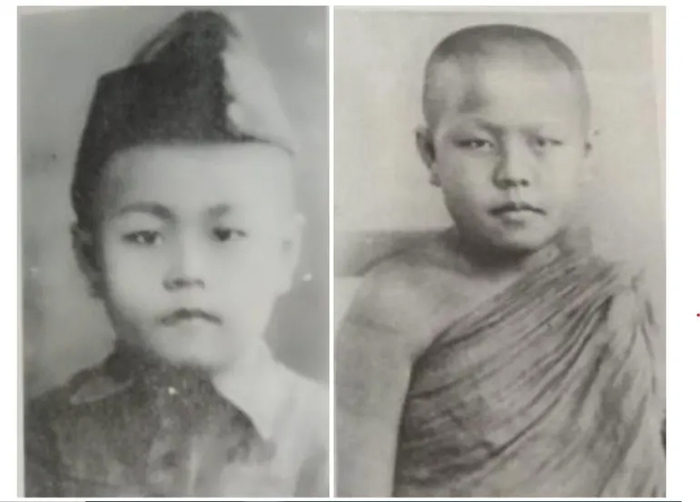

I’m greeted by Ajahn Sulak Sivaraksa, the highly respected and wildly outspoken social critic, activist, writer, and founder of various humanitarian movements across Southeast Asia. Born in 1933, Ajahn Sulak began his spiritual journey as a young monk in the forest tradition of Theravada Buddhism, and then went on to study law in the UK. Returning to Thailand, he founded the International Network of Engaged Buddhists, which connects Buddhists around the world and promotes the integration of Buddhist practice with social action for a healthy, just, and peaceful world. Over the years, Ajahn Sulak has become known for his unwavering commitment to social justice and environmental sustainability and is widely regarded as one of the most influential Buddhist thinkers of our time.

During our conversation in his serene garden, Ajahn Sulak shares his thoughts and experience on a wide range of topics, from the meaning of refuge in Buddhism to the status of women in Buddhist societies. He speaks eloquently about the experiences leading up to the inception of socially engaged Buddhism and shares his insights into how Buddhism can be applied to the modern world in various ways to alleviate suffering and promote well-being for all beings.

Throughout the interview, Ajahn Sulak's warmth, compassion, and wisdom were palpable, and his words served as a powerful reminder of the transformative potential of Buddhist practice in our lives and in the world around us. It was an unforgettable experience to sit with this remarkable teacher and hear his insights, and we hope that our conversation will inspire you to engage with the teachings of Buddhism in ways that promote greater understanding, compassion, and social action. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: For seven decades, you’ve been a leading voice for democracy and human rights in Southeast Asia, and especially your native country of Thailand. Could you tell us about the life events that shaped your worldview and your involvement with social activism?

Ajahn Sulak Sivaraksa: My father attended Christian schools and felt that I should follow in his footsteps, so I went to both Protestant and Catholic schools. I didn't like it because they were very old-fashioned. They beat you and wanted you to learn by rote!

Luckily or unluckily, the school was bombed, and we had to go live in a school upcountry. I refused to go. My father suggested, "Why don't you join the monkhood while you can't go to school?" and I said, "OK!" I joined the monkhood as a sāmaṇera, a novice, and I loved it so much that I didn’t want to disrobe. My father argued that while being a monk is wonderful, if later on you want to leave the monkhood and join the modern age, how could you make a living? He said that it would be better to come out into the world and learn more.

So, I came out of the monkhood after 18 months. At the age of 19, I left Thailand and went to Britain for my further education to study law. After eight years in the UK, I returned home and started a journal called the Social Science Review, which became very well-known. In Thailand, we had been living under a dictatorship for so long, and I introduced something with a different, liberal outlook, and so I too became very popular.

One day, a Thai prince came to me and asked, “What do you do?” I told him that I was the editor of an intellectual magazine, and he replied, "Sulak, do you know the farmers?" I said, "Well, I buy rice from them, I hope they're getting a fair price." And he said, "No, they're not getting a fair price at all. The government keeps the price of rice low, so that you middle classes stay happy. But the farmers have been oppressed. If you don't know how the farmers are suffering, then your intellectual magazine is in fact just intellectual masturbation."

So, I followed the prince's advice and got to know the farmers. That completely changed my outlook. I wanted to be with the poor. Since then, I've been arrested many times, simply because I side with the poor.

Yes, I read that you’ve been arrested many times, been forced into exile for a while, and faced 15 years in jail! Incredible. Throughout your life, you became very close with Thich Nhat Hahn, who himself was known for leaving monastic isolation to help victims of the Vietnam War, starting the “engaged Buddhism movement.” How did you develop this concept into the “socially engaged Buddhism” term you coined?

When French colonialism came to Vietnam, the Buddhists retreated. The Vietnamese who became Catholic and learned French got good positions in the government, while the Buddhists were left behind. Later on, the Americans came, and there was the Vietnam War. Thich Nhat Hanh said, "We Buddhists must awaken! We must not only prepare for the next world, we must also bring Buddhism to this world!" And he coined the term "engaged Buddhism."

He and I became great friends. I took these words from him, and I tried to make them a little bit more precise: "socially engaged." It means we engage with society and try to improve society ourselves. That's how the term "socially engaged Buddhism" came about.

I started the International Network of Engaged Buddhists almost 40 years ago now.

We have members all around the world, but it's still small. A lot of Buddhists still don't want to be engaged; they only want to sit down doing their own meditation!

I think in the West, many Buddhist practitioners regard Buddhism as something quite separate from society, or that the government and charities should be the ones handling social issues. As such, socially engaged Buddhism can sound new or even alien to many Buddhists, who might think that meditation is removed from everyday issues or politics. What is the reason behind this mindset?

Quite a number of Westerners have become Buddhist, particularly in England, like Mr Christmas Humphreys, the founder of The Buddhist Society some 90 years ago. He said to me, "Buddhists must learn to meditate and not get involved in society." He said that the Christians had gone wrong, because they were involved with society and politics, leading to the loss of the spirituality of Christianity. Therefore, he thought, Buddhists must not follow this bad example of the Christians.

Particularly in the West, people who join Buddhism tend to come from the middle and upper classes. At that time when I joined The Buddhist Society in London, the British Empire was still around. The British didn't realize that their empire created so much suffering around the world.

A lot of Buddhists in the West meditate. But I argue that only meditating, without understanding social suffering, environmental suffering, that's not Buddhism, it's escapism!

It’s like in Japan, where Buddhism on the whole deals with the next world, and the priests make a lot of money on funerals. They don't care for the present world. We Buddhists must care for this world, as well as the next world.

It’s rare for people – especially Buddhists – to speak badly of meditation! You just mentioned that meditation has the potential of simply becoming a form of escapism, so are there right and wrong approaches to meditation?

In our tradition, the key training in Buddhism is called tisikkhā: the threefold training in education. The first one is sīla, right conduct. Sīla in the modern context means learning

not to exploit oneself and others. For me, that is key. But in the West, they only concentrate on cittasikkhā, or developing mindfulness. But without sīla, mindfulness could be dangerous.

In Thailand, we have a group of monks called Dhammakaya. They help people to meditate in order to become richer and richer. That's awful! Or think of the Japanese who meditated and became so concentrated, and then went and sacrificed their lives to bomb Pearl Harbor. I think that's wrong. You see, meditation must have sīla. Without sīla, meditation can become wrongful meditation. In Buddhism, you have either sammāsamādhi, the right kind of meditation, or miccāsamādhi, meditation with a bad result. I think that's very, very clear in the teachings of the Buddha, as I understand them.

I’ve read that aside from Thich Nhat Hahn, you’ve spoken of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, the 20th-century champion of social justice and civil rights for the "untouchable" Dalit caste in India, as being one of your greatest inspirations. What is it about his work that speaks to you?

Many people among the younger generation are coming back to the essence of Buddhism. Not only in this country, but in Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, and particularly in India. As you know, a lot of Indian untouchables have now embraced Buddhism, a trend started by Dr. Ambedkar 60 years ago.

Ambedkar was an untouchable, but he was the most educated one at that time, because he got his PhD from Columbia University, studied at LSE, and he was called to the bar. But since he was an untouchable, he was still “the lowest of the low.” He said that although he was born a Hindu, he wouldn't die a Hindu. He embraced Buddhism, and he felt that Gandhi compromised too much by accepting the caste system.

Ambedkar said that he would never accept the caste system. When he embraced the teachings of the Buddha, more than 500,000 people joined him. 60 years later, there are more than 10 million Indian Buddhists, because Ambedkar found that the teachings of the Buddha give liberation.

The caste system is very oppressive, with the brahmins at the top, the kshatriya or warrior class second, then the merchant class, and at the bottom the shudra, the laborers. But even “worse” than that are the untouchables, who are seen as being beyond the four castes.

Ambedkar said that the French rhetoric of liberty, equality, and fraternity during the French Revolution was just rhetoric, because the French used violence. After killing the king, soon Napoleon came and there was more and more violence. Whereas the Buddha started the Sangha. The Sangha is an alternative society from the mainstream. Anybody who joins the Sangha, whether you are the son or daughter of a king, or the son or daughter of a prostitute, you are all equal in the Sangha. The Sangha uses fraternity, brotherly love and sisterly love, and this is expressed to the lay community. Brotherly love is a key teaching of the Buddha.

What other teachings of the Buddha inform or strengthen your commitment to social justice?

All of the teachings of the Buddha have helped me in my struggle for social justice in Thailand. The Buddha said that you are not a mature person unless you develop the brahmavihārās, the four immeasurable attitudes. The first step is mettā, loving-kindness. You must learn to love yourself and to love people around you. To love humanity is easy, but to love the people around you is difficult, because they've done all kinds of things to harm you. The next step is called karuṇā, compassion. Karuṇā means that you must share the suffering of the poor and the oppressed, to be with them. Not just helping them, but to suffer with them. Then you develop muditā, to have joy and to learn not to hate the oppressor. And then with that you develop upekkhā, you develop how to be mindful, how to have equanimity and know when to use mettā, when to use karuṇā, when to use muditā.

Unlike the Marxists, we don't hate the oppressor. We must be kind to the oppressor. But we must change the oppressive system. That is my understanding of how to change the predicament in the world now.

In the middle of the 20th century there was considerable trust that poverty and inequality could be eradicated, yet here we are, 60 years later, in pretty much the same predicament. In your book, Wisdom of Sustainability: Buddhist Economics for the 21st Century, you propagate Buddhist economics. Can you tell us more about this concept?

At one time, we thought that democracy would solve every problem. But it didn't work. Then the Americans gave the idea that development would be the answer. Instead of colonialism, they used the word "development." But for me, it's just a different kind of colonialism.

The Americans would tell you that you are underdeveloped and should be more capitalistic. The UN called the 1960s the "decade of development” but by the end of the decade, the rich had become richer, and the poor had become poorer. It's all wrong because it's only about materialism. That's why I admire the Bhutanese king, who said that we must develop Gross National Happiness, not Gross National Product. I think that's the key. We have to limit greed.

Luckily, there are now alternatives. In economics, E. F. Schumacher came up with "Buddhist economics" more than 40 years ago. It was economics, but as if human beings mattered. And now there's even Schumacher College in England, promoting alternative education. Likewise, in politics, there's a book by Glenn Paige called Nonkilling Global Political Science. Paige also became a Buddhist, living in Hawaii, and he became my good friend.

Buddhism teaches you to look for something alternative. So, if the world is getting more and more greedy, you must learn to limit greed. If the world is getting more and more violent, you must learn to change violence into non-violence. If the world is full of delusion,

just like modern education is full of delusion, and just like modern mass media is full of delusion, we have to try to change that into wisdom, the alternative to delusion. It's possible.

You just mentioned that the modern education system is full of delusion and that we need to look for alternatives. You founded the Spirit in Education Movement as an attempt to provide a transformative experiential education for students that also shines a light on the root causes of societal injustice. Can you tell us more about this movement?

A lot of young people now are tired of mainstream education and they're looking for something alternative. Western education is entirely about developing the head, not the heart. I'm one of those involved in alternative education. We call it SEM, the Spirit in Education Movement. The key point of this education is to develop good friendships, kalyāṇamitra. The students learn from the teacher, and the teacher learns from the students. We are honest with each other, that's the first step. Then we expose both teacher and student to suffering in the world. If you come from the middle classes, go to learn from the lower classes, how they suffer, and understand structural violence.

You are in the middle, and mainstream education teaches you to climb up to the top. But our approach is that we are in the middle, and we must realize that we are in the structure of oppressing the poor. We must go to learn from the poor. We must use the four brahmavihārās of loving-kindness, compassion, equanimity and so on.

You’ve talked about oppression and violence. Should we fight oppression with violence? In the modern age where we have access to such a huge amount of information highlighting the atrocities of oppressors across the globe, how can we avoid feeling hatred for the oppressor yet still take deliberative action?

First, we must learn that we also have oppression in ourselves. Because we don't cultivate ourselves properly, our egos become big. Sometimes we feel like we are nobody, so we want to be recognized. The ego is very essential here. But if you learn to breathe properly, you tame the ego. And you'll see that the ego is not real. Even if you cannot get to that stage, learn to make fun of yourself, learn to belittle yourself. Then learn to interrelate with others.

We are interrelated. Not only humans and humans, but we are interrelated with the trees.

Without the trees, we cannot breathe properly so the trees help us a great deal. This is what the Buddha teaches us, to learn from Mother Earth, from the trees, from the oceans.

Skillfully, we can change the oppression that exists within ourselves, and then try to change oppression on the outside. Inside and outside are interrelated. In my opinion, you cannot have one without the other. If you see things in black and white, as good and evil, that's dangerous.

When we denounce something as evil, subconsciously we ourselves become evil. When we hate somebody, subconsciously we imitate that person we hate. So, the Buddha said to just learn. That other person, no matter how bad they are, they also have Buddha nature. The Quakers say, "Everyone has God inside." Learn to see the goodness in others, and how to relate to them, how to develop kalyāṇamitra – to be good friends, and then things will change.

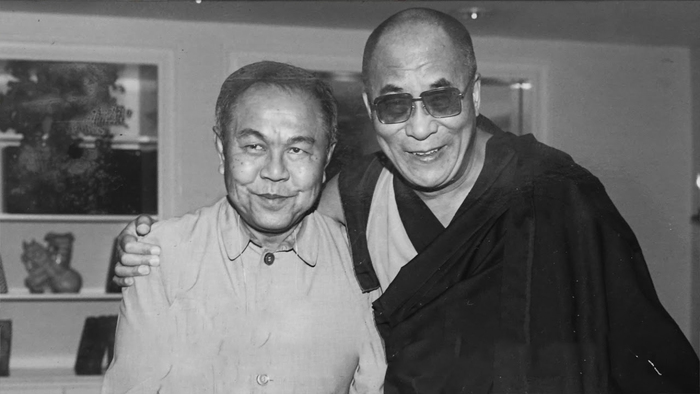

The Dalai Lama talks always of love. The future of the world depends on love, not on violence. Even the Chinese must learn to change. The Chinese, after all, had deep wisdom in the past: Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism. After Mao Zedong came, he destroyed so many things, killed and uprooted so many people in the name of communism. But I think the Chinese also have much wisdom, and one of these days they will go back to their roots. The Dalai Lama keeps on telling us that we must love the Chinese. Only with love will things change.

So, if we can see the good – or the Buddha nature – in others, and develop the brahmavihārās, that will be enough?

Well, the key word, particularly in Mahayana Buddhism, is upāya. You must learn to be skillful. If you care only for yourself, it's escapism. If you care entirely for others, and don't

care for yourself, that is ignorance. Once we become skillful, once we become less selfish and care more for others, we realize that we are interrelated. We change ourselves in order to change the world. I think for me, that is the essence of the teaching of the Buddha.

When we are interrelated, I care for you, you care for me, and we care for all sentient beings. That is the essential teaching we have to learn to apply appropriately and with urgency in the modern world.

Another important element of socially engaged Buddhism is what you often refer to as having spiritual friendships, kalyāṇamitra. Why is having friends so important?

My understanding is that people need good friends. The Buddha said that also. Ananda asked the Buddha, "Is a good friend – kalyāṇamitra – half of the holy life?" And the Buddha said, "No. A good friend is the whole of the holy life." A good friend is the one who tells you what you don't want to hear. He becomes your extra voice of conscience.

If you hear something you don't want to hear, you reflect. If they tell you nonsense, forgive them. If they tell us something that is our weak point, we must learn to change our weak point and make it strong. So that's why good friends are very important. The International Network of Engaged Buddhists started with our good friends. The Japanese used to care only for the next world. Then soon, they learned to care for the present world with us.

For many, spiritual friendship will bring to mind the Sangha, in which you take refuge, along with Buddha and the Dharma. What is refuge for you?

In Buddhism, we take refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Most people understand Buddha as a big statue, a historical man. But in fact, Buddha means "awakened."

The essence is that the Buddha is awakened, and the Dharma is the way leading you to awakening. But with this awakening, you need the Sangha, you need a community to live together in order to be equal, to have fraternity, and to liberate yourself from greed, hate, and delusion. When people feel weak, they go to big images, they go to big mountains and trees, asking for refuge. That could help you temporarily to make you feel secure, but the real refuge you take is in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Because the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha help you understand suffering, the cause of suffering, and the noble eightfold path to overcome suffering.

That's why you take refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. It's the real refuge. You come to understand your own power inside to change suffering into something beyond suffering. Not only personal suffering, but social and environmental suffering too.

You said that your work with the poor and the oppressed requires you not just to help others but to feel their suffering. How do you view and deal with the suffering of others or, indeed, our own suffering?

Instead of running away from suffering, we must confront it. Dukkha is not only personal suffering, it is also social suffering, environmental suffering. Dukkha is not only suffering, dukkha is unsatisfactoriness, a sense of lack, a sense of fear.

But the four noble truths tell you that you cannot escape these fears. Consumerism says you can escape by consuming more and more. It's all false. You must confront your fears and find out the cause. The root causes are greed, hate, and delusion. Confront them mindfully, with your head and your heart; confront them skilfully, then you can change something negative into positive. With less selfishness, with good friends, we can learn the alternative to suffering, which is something non-violent. Non-violence is something that might not look strong, but just as water can be still, so too can the current become very strong.

You are a well-known and outspoken advocate for the full ordination of nuns. What is Buddhism’s view of women and nuns in particular?

The Buddha regarded men and women as equal. 2500 years ago, this idea was very unusual. In Confucianism, we have male chauvinism. In Hinduism, we also have male chauvinism. I'm not quite sure about Islam and Christianity. But the Buddha said that men and women have the same ability to be enlightened. We can all become buddhas.

But we Buddhists don't live the teachings of the Buddha. In our Buddhist history, male chauvinism is everywhere. Unfortunately, the lineage of the female sangha disappeared about 1000 years after the Buddha and that made the men become even more chauvinistic. But luckily, if you go back to the root teaching, you can revive it.

In Sri Lanka, the bhikṣuṇī [fully-ordained nun] ordination disappeared, but now they've revived it. In Thailand, the mainstream sangha and government don't accept bhikṣuṇī ordination. Bhikkuni Dhammananda is a pioneer in promoting the bhikṣuṇī ordination in Thailand. I support it. We must learn the essential teachings of the Buddha and not let culture or institutions oppress the female sections of society. That is essential.

In Taiwan, there are six times more bhikṣuṇīs than bhikṣus [monks] and they've done wonderful things. There are no sexual scandals, no financial scandals. They work for social welfare, for social change. It's tremendous. In Taiwan, the Taiwanese Buddhists care very much about social welfare. The Tzu Chi Foundation has done wonderful things for social welfare. But ultimately you need social change, to change society non-violently. This is where Bhiksuni Chao-hwei is a leading lady in Taiwan. I think Buddhism needs to be involved in social welfare and social change.

If we men learn from women, we can become more mature, learn to be more humble and become more respectful to the other gender, which we have been exploiting unconsciously for so long.

Dear Ajahn Sulak, thank you so much for distilling your decades of work and experience throughout this short but enlightening interview!