The mind is the individual, subjective experiencing of “something” that is always changing, moment to moment.

The concept of “mind” is elusive, and different languages conceptualize it differently. The Buddhist term for mind in Sanskrit is chitta, and has a wide range of meaning. It includes sense perception, verbal and abstract thought, emotions, feelings of happiness and unhappiness, attention, concentration, intelligence and more. When Buddhism speaks about mind, it refers to every type of mental activity.

The focus is not the physical basis – the brain, nervous system, hormones and so on – nor the chemical or electrical activity involved. Buddhism doesn’t negate any of these, because of course they do exist and are integrally involved. Mind doesn’t refer to some immaterial “thing” that occupies the brain and produces its activity, either. Furthermore, Buddhism doesn’t assert a collective unconscious or universal mind.

What is Mental Activity?

If mind and mental activity is the individual, subjective experiencing of something, what exactly does it mean to be angry, for instance? It is the arising of anger and feeling it, which occur simultaneously. Together they describe one event in an ongoing stream of experiencing something. Whose experience? if I’m angry, it’s my experience, not yours. But there’s no separate me pressing an anger button on a machine called “mind” – we are simply part of the event of experiencing.

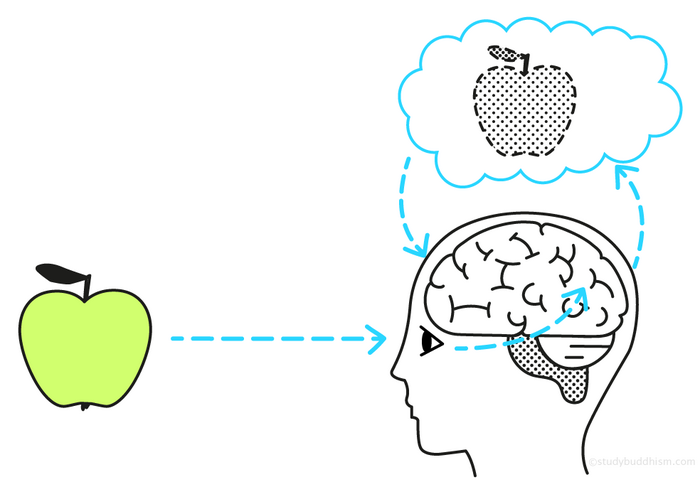

It’s similar to when we see something, like an apple. From a scientific understanding, light rays enter our eyes through our corneas, meeting the photoreceptor cells of the retinas. This triggers electrical impulses that convey optical information to the brain, where it’s processed. The subjective experience of this is the arising of the mental hologram of an apple and this is what it means to see it. The mind, however, is not an empty space somewhere in the brain in which this hologram of an apple arises as suggested by the expression “having something in mind.”

Mental holograms can also be representations of sounds, smells, tastes and physical sensations, even in our imagination and dreams. The image of the arising of a mental hologram can also describe the arising of emotions and levels of happiness or unhappiness, based on the secretion of hormones by various other parts of the brain. In any moment, the content of our mental holograms is a complex of many factors: an object such as a sight or a thought, with a blend of emotions, plus some level of happiness or unhappiness.

[See: What is Happiness?]

Neuroscience and Buddhism

Since the inauguration of the Mind and Life Institute in 1987 by the Dalai Lama and the Chilean neuroscientist Francisco Varela, international teams of scientists and accomplished Buddhist teachers have been exploring the interface between the mind and the brain. Neuroscientists have monitored the brain activity of both novice and experienced meditators, revealing that sustained meditation affects the neuroplasticity of the brain, forging new neural pathways that make it easier to generate concentration and positive emotions like compassion.

Thus far, the findings of Western science and Buddhism have supplemented and enriched each other, and joint ventures between Buddhist practitioners and eminent scientists are the hallmark of what the Dalai Lama calls for – 21st century Buddhism.

The mental activity of experiencing life is what Buddhism means by “mind.” This activity changes every moment and is always accompanied by various mental factors. Buddhism teaches us that we’re not victims of whatever life throws at us, but rather we play an integral role in how and what we experience in life. Through training our minds, we can radically transform our experiences for the better, and with sustained effort, this positive change will become effortless.

[For a more detailed introduction to the mind, see: "The Mind According to Buddhism" by Alexander Berzin.