The Founding of the Qarakhanid Empire

When the Orkhon Uighur Turks were driven from Mongolia by the Kyrgyz takeover in 840 CE, they lost possession of the sacred earth-goddess mountain Otuken near their former capital, Ordubaliq. According to the pre-Buddhist and pre-Manichaean Tengrian beliefs of the Old Turks, whoever controlled this mountain was the theoretical ruler of the entire Turkic world. Only he and his descendants had the spiritual authority to assume the title qaghan, and only his tribe could provide political leaders for the other Turkic tribes. The spiritual force (qut) representing the fortune of the Turks as a whole resided in this mountain and would embody in the qaghan as his own vital force or charismatic power responsible for his success or failure.

The rulers of the two major kingdoms constituted by Uighur refugees, the Qocho Uighurs in the northern Tarim Basin and the Yellow Yugurs in the Gansu Corridor, did not qualify for this politico-religious title since their dominions did not extend to Mongolia. Neither did the Kyrgyz ruler of Mongolia itself, since the Kyrgyz were racially a Mongolian people and did not originally speak a Turkic language. They were a people of the Siberian forest, not of the steppe, and did not believe in the sanctity of Otuken.

There was a second sacred mountain, however, Balasaghun, on the Chu River in northern Kyrgyzstan near Lake Issyk Kul. It had been under the control of the Western Turks who had built several Buddhist monasteries on its slopes. As the mountain now lay within the Qarluq Turk domain, the Qarluq ruler, Bilga Kul Qadyr, in 840 declared himself “qaghan,” the rightful leader and protector of all Turkic tribes, and changed the name of his kingdom and dynasty to Qarakhanid (Karakhanid).

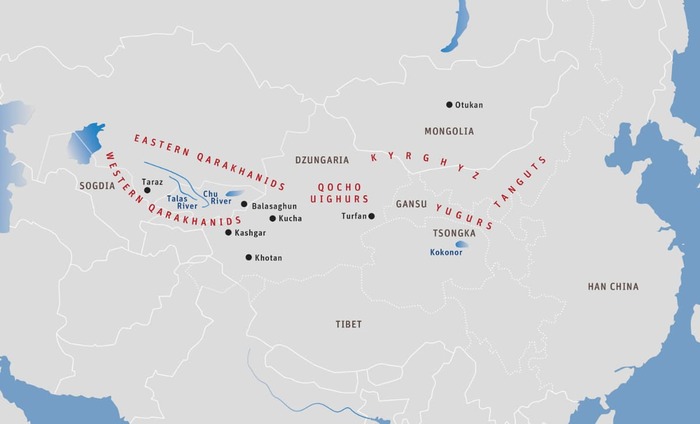

Soon after its founding, the Qarakhanid Empire split into two. The western branch had its capital at Taraz on the Talas River and included the city-state of Kashgar to the southeast, across the Tianshan Mountains at the extreme western end of the Tarim Basin. The eastern division, to the north across the Kyrgyz Range, centered around the sacred mountain of Balasaghun on the Chu.

Relations between the Qarakhanids and the Uighurs

Throughout their period (840 – 1137), the Qarakhanids never launched a military campaign against their former overlords, the Uighurs, although previously, as Qarluqs, they had frequently fought. Two of the four Orkhon Uighur refugee communities were very small and had settled within the Qarakhanid Empire – in Kashgar and along the Chu River Valley. It is unclear to what extent they became assimilated or if they sustained themselves as alien minorities. The Qarakhanids maintained, however, a cultural rivalry with the other two, much larger groups, the Qocho Uighurs and the Yellow Yugurs. They would try to use other, nonmilitary means to gain ascendency over them.

The Qocho Uighurs became highly urbanized in the northern oases of the Tarim Basin. Having abandoned their former martial traditions of the steppes and adopted Buddhism, they lived mostly in peace with the surrounding kingdoms. The Yellow Yugurs also became urbanized in the city-states of the Gansu Corridor, also became Buddhists, but were in almost constant warfare with their neighbors, the Tanguts, to the east who continually threatened them. Both Uighur branches had friendly relations with Han China, since local Han settlers in the area had helped them depose the region’s former Tibetan rulers and establish their kingdoms.

Together, the two Uighur peoples constituted the only Turkic group at the time with a written language and a high culture, which they had gained with the help of the Sogdian merchants and monks living in both their realms. The Qarakhanids lacked these qualities, despite their control of Kashgar, which also had a Sogdian presence. However, with possession of Balasaghun, they had a strong claim for the leadership of the Turkic people.

Early Relations between the Qarakhanids and Tibet

The Qarakhanids maintained the Qarluq custom of supporting a blend of Buddhism, Turkic shamanism, and Tengrism, as had the Western Turks before them. They also continued their traditional friendly relations with their former, long-term military ally, Tibet. The latter, although politically weak, still exerted a strong cultural influence on the areas immediately to the east of the Qarakhanids. For more than a century after the assassination of Langdarma in 842, Tibetan was the international language of commerce and diplomacy used from Khotan to Gansu. Due to the long Tibetan occupation of the area, it was the only common tongue in the region. Many Han Chinese and Uighur Buddhist texts were transliterated into Tibetan characters for the most widespread use, with some even being sponsored by the Kyrgyz royal family.

As further indication of the close link between the Qarakhanids and Tibetans, after Langdarma’s repression of the Buddhist monastic tradition, three central Tibetan monks escaped persecution by passing through western Tibet and accepting temporary asylum in the Qarakhanid territory of Kashgar. The Qarakhanids were sympathetic to their plight and Buddhism was stable enough in that area for them to feel secure. Proceeding eastward, most likely along the southern rim of the Tarim Basin, and instructing many of their compatriots in Gansu, they finally settled in the Kokonor region of northeastern Tibet, where the Tsongka Kingdom soon was founded. They were responsible for the survival of the monks’ ordination lineage that was revived in central Tibet from Tsongka a century and a half later.

The Saffarid Kingdom

After General Tahir founded the Tahirid state in Bactria in 819, the next local Islamic leader to declare autonomy under the Abbasids was Yaqub bin al-Saffar, who established the Saffarid Dynasty (861 – 910) from his stronghold in Sistan, southeastern Iran. His was an extremely ambitious military rule, which in 867 set out to conquer all of Iran. In 870, the Saffarids invaded Kabul. In the face of imminent defeat, the last of the Buddhist Turki Shahi rulers was ousted by his brahman minister, Kallar, who abandoned Kabul to the Saffarids and established the Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 – 1015) in Gandhara and Oddiyana.

The Saffarid leader plundered the monasteries of the Kabul Valley and sent Buddha statues from them as war trophies to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. This militant Muslim occupation of Kabul was the first serious blow against Buddhism there. The previous defeat and conversion to Islam of the Kabul Shah in 815 had had only minor repercussions on the general state of Buddhism in the region.

The Saffarids continued their campaign of conquest and destruction northward, capturing Bactria and ousting the Tahirids in 873. Their glory, however, was short-lived. In 879, the Hindu Shahis regained control of the Kabul region. They patronized both Hinduism and Buddhism among their people, and Buddhism revived throughout the area.

The Buddhist monasteries of Kabul soon regained their past opulence and glory. Asadi Tusi, in his Garshasp Name written in 1048, describes Subahar Monastery found by the Ghaznavids when they took Kabul from the Hindu Shahis approximately fifty years earlier. One of its temples had walls of marble, doors of gilt, floors of silver and, in its center, an enthroned Buddha made of gold. Its walls were decorated with representations of the planets and twelve signs of the zodiac, identical to the Zurvanite motif found in the throne room of the Iranian Sassanid palace, Taqdis, centuries earlier.

The Samanid and Buyid Kingdoms

Meanwhile, the Persian governors of Bukhara and Samarkand had also declared their autonomy from the Abbasids and had founded the Samanid Dynasty (874 – 999). In 892, the Samanid founder, Ismail bin Ahmad (r. 874-907), captured the Western Qarakhanid capital, Taraz, causing its ruler, Oghulchaq, to shift his capital to Kashgar. Ismail bin Ahmad then took Bactria from the Saffarids in 903, causing their harsh rulers to retreat to central Iran.

The Samanids promoted a return to traditional Iranian culture, but remained politically loyal to the Arabs. They were the first to write Persian in the Arabic script and did much to develop Persian literature. At the height of their rule, under Nasr II (r. 913 – 942), peace prevailed in Sogdia and Bactria, with a high level of culture.

The Samanids were Sunni, but Nasr II was also sympathetic to the Shiite and Ismaili sects. He was also tolerant of Buddhism, as evidenced by the fact that carved Buddha images were still made and sold in the Samanid capital, Bukhara, during this period. The Samanids were even sympathetic to the much-persecuted Manichaeans, and many found refuge in Samarkand during their rule.

The only religious group that felt unwelcome were the Zoroastrians, the followers of the religion of the Samanid founder before he converted to Islam. A large community of them emigrated to India, arriving in Gujarat by sea in 936. There, they became known as the Parsis. Shortly afterwards, Nasr II’s successor, Nuh ibn Nasr (r. 943 – 954), severely repressed the Ismaili sect of Islam.

Throughout this period, the Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad grew ever weaker. Soon after the downfall of the Saffarids in 910, the Buyids established their dynastic rule over most of Iran (932 – 1062). The Buyids were Shiites and, during their reign, effectively controlled the Baghdad caliphs. They continued to support the Abbasid interest in foreign learning, however, particularly science. In 970, a group of Baghdad scholars known as the “Brethren of Purity (Ikhwanu’s-Safa)” published a fifty-volume encyclopedia covering all fields of contemporary knowledge, including material translated from Greek, Persian, and Indian sources.

The Khitan Empire

Meanwhile, another important empire was rising in southwestern Manchuria that would soon affect the balance of power in Central Asia. This was the empire of the Khitans. Apaochi (872 – 926) united the various Khitan tribes in the area and declared himself “khan” in 907, a year after the fall of the Chinese Tang Dynasty. The Khitans followed a blend of the Han Chinese and Korean traditions of Buddhism together with their native form of shamanism. Apaochi had already built a Khitan Buddhist temple in 902 and, in 917, proclaimed Buddhism as the state religion.

The Khitans were the first known group to have spoken a Mongolian language. They had a highly evolved civilization with particular skill in metalwork. Wishing to keep a separate identity for his people, in 920 Apaochi commissioned a written script for the Khitan language, modeled after the Han Chinese characters, but far more complex. In the following centuries, it became the basis for the Jurchen and Tangut writing systems.

In 924, Apaochi Khan overthrew the Kyrgyz and conquered Mongolia. He was extremely broad-minded, however, and tolerated the Manichaean and Nestorian Christian believers left there after the departure of the Orkhon Uighurs. He also extended his suzerainty over the Gansu Corridor and the northern Tarim Basin, where the Yellow Yugurs and Qocho Uighurs submitted peacefully and became vassal states. In 925, he adopted the Uighur script as a second, simpler form of writing Khitan. He even invited the two Uighur groups to return to their steppe lands. However, having well adopted to sedentary urban life and perhaps also fearing a total Khitan takeover of the Silk Route in their absence, the Uighurs and Yugurs both declined.

The Khitan Empire quickly expanded in many directions. Soon, it included all of Manchuria, part of northern Korea, and a great of northeastern and northern Han China. Apaochi's successors declared the Liao (Liao) Dynasty (947 – 1125), which was a constant rival and enemy of the Chinese Northern Song (Sung) Dynasty (960 – 1126). The latter had succeeded in reunifying the rest of Han China after a half century of fragmentation.

Although the Khitan nobility that occupied Han Chinese territory became largely Sinicized, the Khitans outside of Han China kept their own customs and cultural identity. The Khitan rulers always maintained their imperial court and center of military power in southwestern Manchuria. They paid only lip service to Confucian ritual and emphasized instead strong Buddhist customs, which they blended with their traditional shamanic beliefs. Slowly, Buddhist values predominated. The last recorded human sacrifice at a Khitan imperial burial was in 983. The Khitan emperor, Xingzang (Hsing-tsang), took Buddhist precepts in 1039 and prohibited the sacrifice of horses and oxen at funerals in 1043.

Since the Khitans had been familiar with Han Chinese Buddhism for centuries before declaring their dynasty and also because the most extensive Buddhist literature was available in the Chinese language, Han civilization soon overshadowed Uighur elements as the main foreign influence on Khitan society. The Qocho Uighurs and Yellow Yugurs felt increasingly estranged. Subsequently, while maintaining diplomatic and trade relations with their overlords, the Khitans, they pursued a more autonomous course. They never rebelled, however, perhaps for a number of reasons. The Khitans had military superiority. Not only would the Uighur and Yugurs be unable to vanquish them, they would, on the contrary, be able to profit from having them as protectors. Furthermore, both Uighur groups, despite having adopted Buddhism, undoubtedly still had their eyes on the sacred Otuken Mountain in Mongolia, under Khitan control, and did not wish to lose all contact with it. Uighur Buddhism, like its Old Turk predecessor and the parallel Khitan form, combined Tengrian and shamanic elements into the faith.