The Conversion of the Qarakhanids to Islam

During the 930s, Nasr bin Mansur, a prominent member of the Samanid royal family, defected to the Western Qarakhanids and was installed as the governor of Artuch, a small district north of Kashgar. He was undoubtedly trying to infiltrate behind the Qarakhanid lines in order to facilitate a further expansion of the Samanid Empire. Being a devout Muslim, the Samanid ordered a mosque constructed at Artuch, the first in the Tarim Basin. When Satuq, the nephew of the Western Qarakhanid ruler, Oghulchaq, visited the area, he developed an interest in the new religion and converted.

According to Islamic historical accounts, when Satuq tried to convince his uncle to change religions as well, the latter resisted, which led to a prolonged clash. The nephew eventually overthrew his uncle and assumed the title Satuq Bughra Khan. With his declaration of Sunni Islam as the state religion, the Western Qarakhanids of Kashgar became the first Turkic tribe officially to adopt the Muslim faith. This occurred in the late 930s.

Analysis of the Motives for the Conversion

Although religious fervor may have motivated Satuq’s actions, he undoubtedly had an additional reason – ambition for power. In order to achieve his aim of ruling the Qarakhanids, he allied himself with the Samanid infiltrator who also had a similar objective. To gain his trust, Satuq would need to adopt a strategy.

The Iranian Samanids had followed the Arab Abbasid custom of taking Turkic tribespeople as slaves and conscripting their warriors into their army. Although the Samanids were exceptionally tolerant of other religions, they would nevertheless offer these slaves nominal freedom if they converted to Islam. More than a thousand Qarakhanids living in Samanid territory had changed religions in this manner. If Satuq voluntarily submitted himself and his followers to Islam, he would easily gain the confidence of the Samanids and seal a military alliance.

Furthermore, if Satuq had ambitions of his own to turn the tide of Western Qarakhanid losses of territory and forge the Turks into a regional power, his move would be facilitated by unifying his people around a new religion. This was the time-tested pattern of previous Tibetan, Eastern Turk, and Uighur successes. The combination of Buddhism and shamanism had failed to provide the supernatural support for his uncle to keep control of his lands across the Tianshan Mountains; whereas with Islam behind them, the Samanids had succeeded in gaining the victory. The choice of new religions was obvious.

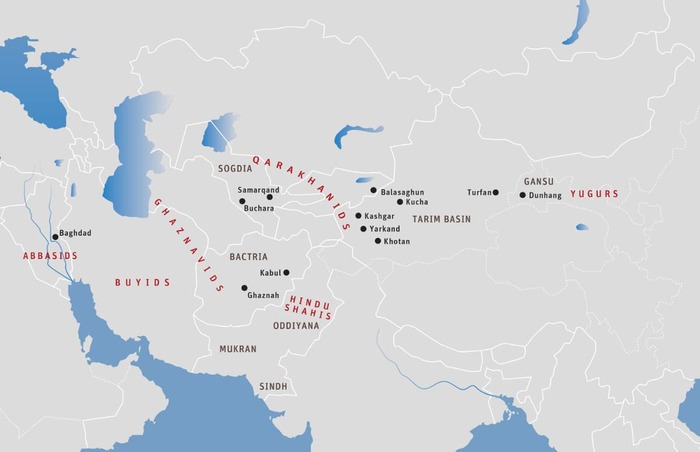

The Qocho Uighurs were currently thriving as the upholders of Buddhism and lords of the northern branch of the Silk Route through the Tarim Basin. Their ethnic cousins, the Yellow Yugurs, also strong Buddhists, controlled the Gansu Corridor where, after the northern and southern branches joined at Dunhuang, the Silk Route funneled into Han China. In order to rally the Turkic tribes behind his ambition, away from the Uighurs, Satuq needed a religion not only different from Buddhism. He needed one that also would allow him to reopen the alternative southern branch of the route and shift the focus of control of the trade from the eastern to the western sectors.

As the western terminus of the Silk Route in Sogdia was in Islamic hands, Satuq’s plan seems to have been to conquer Sogdia. Then, driving eastward from Kashgar, he could use Islam to forge a cultural unity along the southern branch of the route and on through the Gansu Corridor, with himself as protector and overlord. Just as the Uighurs had used the flag of Buddhism to win and consolidate their hold on the northern Tarim branch of the Silk Route, Satuq apparently hoped to accomplish the same for the Qarakhanids with the southern branch under the banner of Islam. First, however, in order to rally the Turkic peoples behind him, he required the Turks’ sacred mountain to turn the supernatural advantage to his side.

Consolidation of the Qarakhanid Islamic State

In 942, Satuq Bughra Khan, with the help of his Samanid allies, tried to conquer the Eastern Qarakhanids and gain control of Balasaghun. Being unsuccessful, he then turned against the Samanids themselves, helping local opposition groups to undermine their rule in Sogdia. This is added evidence that political ambition outweighed any feelings he might have had of religious kinship with his fellow Muslims.

Over the next decades, Satuq’s successors not only won Balasaghun and reunified the Qarakhanids, but also took Samarkand and Bukhara from the Samanids. As overlords and protectors of the Turks’ sacred mountain, they assumed the title qaghan by the end of the century. They could now turn their attention to their main objective, the southern Tarim branch of the Silk Route.