First Contacts with Buddhism

After the fall of the Han Dynasty in 220 CE, Buddhism became strong in northern China, which was fragmented and ruled by a succession of non-Han Chinese people and states. The greatest patron of Buddhism among them was the Toba Northern Wei Dynasty (386 – 535), which spanned Inner Mongolia and northern Han China.

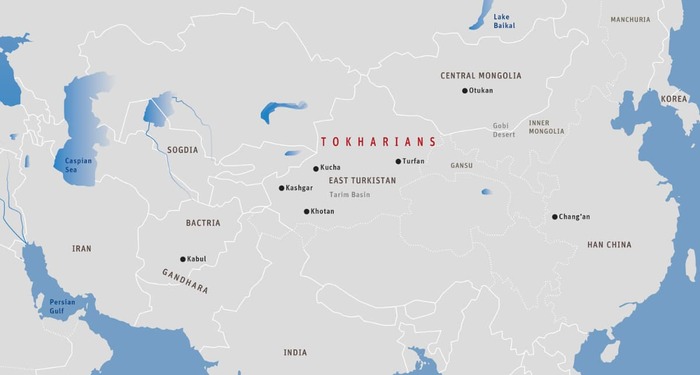

The Old Turks, the earliest recorded group to have spoken a Turkic language, emerged on the pages of history as a class of metalworkers living in the cities of the Toba realm. Their origin, however, was undoubtedly as a nomadic tribe from the steppes to the north since their sacred mountain, Otuken, was located in central Mongolia on the other side of the Gobi Desert from Toba-held lands.

The Old Turks followed a religious tradition that blended shamanism with what Western scholars have named “Tengrism,” a faith worshiping Heaven (Turk. Tengri) as the supreme God and venerating certain mountains as seats of power. Tengrism was never an organized religion and appeared in several forms among almost all the peoples of the Central Asian steppes – Turk, Mongol, and Tangut alike. In its Turkic form, it supported the Turkic social structure, which was built on the basis of a hierarchy of tribes. One tribe is dominant and its chief is the source of a hereditary line of rulers for all.

The Turkic form of Tengrism, then, regards any Turkic chief controlling Otuken as supreme ruler (Turk. qaghan) of all Turkic tribes and embodiment of society’s fortune. If Turkic society’s fortune declined, the qaghan was accountable and could even be sacrificed. His son would then succeed to his position.

With such a belief system, the Turks first encountered Buddhism in the Toba cities. This was specifically in its northern Chinese form emphasizing devotion by the public and subservience of religious clerics to the state. This social of Buddhism fit comfortably with Turkic Tengrian ideas of tribal hierarchy.

Dissatisfied with Toba rule, the majority of Turks moved west to Gansu, under the dominion of the Ruanruan state (400 – 551). The Ruanruans ruled the deserts, grasslands, and forest regions from Kucha to the borders of Korea, including a large part of Mongolia. As the Ruanruan gradually adopted the Tocharian and Khotanese forms of Buddhism found in the East Turkistani oasis cities they controlled and spread it throughout their realm, the Old Turks met with this Iranian-influenced form of Buddhism as well. In a Zoroastrian milieu, Buddha became a “king of kings,” a “god of gods.”

Bumin Khan overthrew the Ruanruan in 551. Assuming the guardianship of Mount Otuken, he declared himself qaghan and established the Old Turk Empire. Two years later, it split into an eastern and western division.

The First Eastern Turk Empire (553 – 630), founded by his son, Muhan Qaghan (553 – 571) and centered in Mongolia, inherited the Turkic spiritual legacy of shamanism and Tengrism. As this religious tradition lacked an organized structure, it was weak in providing a unifying force for building a new nation. Looking to the Ruanruan and Toba Wei states for models, the Qaghan realized that Buddhism was capable of the task. Therefore, as the Turks were already acquainted with the northern Chinese and Tocharian/Khotanese forms of Buddhism, the Qaghan was keen to establish more contact with this faith and fit it into the envelope of traditional Turkic belief. Just as Buddhist monks prayed for the welfare of northern Chinese Buddhist states, they could do the same for the Eastern Turk Empire. Moreover, just as Buddha’s entourage had expanded to include all Zoroastrian gods, with Buddha as their king, it could further enlarge to accommodate the multitude of Turkic gods (tengri) as well.

After the breakup of the Northern Wei Empire, its smaller successor states continued its patronage of northern Chinese Buddhism. Two of them, the Northern Qi (Ch’i) (550 – 577) and the Northern Zhou (Chou) (557 – 581), became tributary states of the Eastern Turks. As a sign of friendship, the Northern Qi minister built a northern Chinese-style Buddhist temple for the six thousand Turks still living in Chang’an. Muhan Qaghan gladly reciprocated the gesture by inviting several Han Chinese monks north to his stronghold in Mongolia to instruct his people.

The Adoption of the Sogdian Language for Secular Use

As successors to the Ruanruan, the Eastern Turks ruled the Tocharian oasis of Turfan. Many previous ethnic groups of nomadic peoples from the Mongolian steppes or the desert fringes, such as the Toba Wei, had adopted Han Chinese culture and then lost their identity. Aware of this precedent, Muhan Qaghan wished to avoid this happening to his people as well. Therefore, soon after establishing his Eastern Turk Empire, he turned to the Sogdian merchant community of Turfan to provide it with a non-Chinese written language for administrative and financial purposes.

The Qaghan chose Sogdian, as it was the only Central Asian language of the Tarim Basin at the time to have a written form. Its use was limited to the secular sphere, originally business, and was found not only in Turfan, but also all along the Silk Route. Local tongues, such as Tocharian and Khotanese, were still strictly oral at that time.

Religious Persecution in Han China and Sogdia

Between 574 and 579, during the reign of the second Eastern Turk qaghan, Tapar (r. 572 – 581), the Northern Qi and Northern Zhou tributary states of the Eastern Turk Empire instituted a persecution of Buddhism. It was primarily due to the influence of Daoist ministers jealous of government support of the monasteries. Many more Han Chinese monks and four visiting Gandhari Buddhist translators from Kabul, led by Jinagupta (528 – 605), fled from Chang’an to the Eastern Turk court. There, they joined ten Han Chinese monks who had just returned from India with 260 Buddhist texts for translation and who, like them, were also receiving asylum.

At approximately the same time as this development in northern Han China, the Sassanid emperor, Khosrau I (r. 531 – 578), was severely persecuting Manichaeism and what he considered heretical Zoroastrian sects in Iran and Sogdia. This caused a new wave of migration of religious refugees to the oasis cities of East Turkistan. Due to the efforts of the Manichaean missionary, Mar Shad Ohrmizd (d. 600), who accompanied the immigrants, the Sogdians – especially in Turfan – began for the first time to translate Manichaean texts into their language from the original Parthian and Syriac versions used in their homeland. They most likely took this step because they were convinced of the necessity for their religious community to be independent of the vicissitudes of politics at home and to become self-sufficient.

The First Written Translations of Buddhist Texts into Tocharian

In East Turkistan up until this time, Buddhist texts were written, studied, and chanted primarily in the original Indian languages of Sanskrit or Gandhari Prakrit, or sometimes in Chinese translation. There is no evidence of Buddhist scriptures having even been translated into Central Asian languages up to this point, let alone committed to writing. The first signs of such activity appeared only now in the mid-sixth century.

The earliest written Tocharian documents date from this period and are translations of Buddhist texts from Sanskrit into the Turfanese dialect. Perhaps the Tocharian Buddhists of Turfan were inspired by the Manichaean Sogdians in their midst to take this step, also to ensure their independent and individual cultural identity. Although earlier Tocharian Buddhist masters, such as Kumarajiva (344 – 413), had actively participated in translating Indian texts into Chinese, the Tocharians had continued to maintain their own form of Buddhism based on the Sanskrit scriptures. Because they viewed the oases along the northern rim of the Tarim Basin as their homeland and had no contact with their original European roots, and because their cities had been ruled by a succession of foreign dynasties, the issue of maintaining an independent cultural identity would have been important to them. The persecution of Buddhism in Han China undoubtedly added weight to their decision to write down their language and translate their scriptures.

The Sogdian Forgoing of Translating Buddhist Texts into Their Own Language at This Time

The Sogdian Buddhist community of Turfan, however, did not follow the Sogdian Manichaean or Tocharian Buddhist example of translating their scriptures into their language and committing them to writing. They did not take this move for another century for a complex of possible reasons. Let us postulate some of them.

Firstly, the Sogdians of East Turkistan were merchants and traders and, unlike the Tocharians, probably did not feel any particular allegiance to the city-states in which they lived. They never regarded them as their homeland, but looked instead to Sogdia. Establishing an individual identity, then, for an occupied homeland in which they were now living was not so pertinent to them.

Secondly, the expatriot Sogdian community in East Turkistan was multireligious. They were unified by their occupation and written language used for their trade. Unlike the Tocharians, they did not need to use religion for this purpose. Furthermore, unlike the Manichaean Sogdians who had no direction to turn to for religious support other than Sogdia and the rest of the Sassanid Empire, the Sogdian Buddhists of Turfan could look toward Han China. They seemed not to be particularly attached, then, to the language of their religious texts. They seemed to have felt equally at ease with the Sanskrit and Gandhari Prakrit versions used in their homeland, as well as the Chinese translations they had also helped to prepare. Despite the persecution of Buddhism in Han China and unstable religious situation in Sogdia, they apparently did not see any reason to translate their texts into their own language at this time.

If the Sogdian Buddhists of East Turkistan wished to take distance from the religious insecurity in their homeland, they could use more Chinese in their religious practice. Their Manichaean brethren, on the other hand, when faced with a similar situation, had no choice but to establish their own tradition in their own native tongue. In using Chinese for religious purposes, the Sogdian Buddhists apparently did not feel their cultural identity threatened, since that identity was based on factors from their secular life. In fact, the trend of the Sogdian Buddhists in East Turkistan to rely more strongly on the Chinese language and tradition in their religious lives quite likely received impetus from the wave of Manichaean Sogdian refugees into their midst. The newcomers also rejected the religious languages of their birth.

The Translation of Buddhist Texts into Old Turk

Tapar Qaghan, however, had different priorities from the Sogdians. As ruler of a newly established empire, he did not wish his subjects, the Eastern Turk people, to rely on the Chinese language in any way. His predecessor had followed the policy of using a foreign tongue in the secular sphere by adopting both the Sogdian language and the Sogdian script. As the Sogdians did not have their own state, there was nothing threatening in this move. With an influx of Han Chinese refugee monks into his realm, however, Tapar now felt the pressing need to establish an identity for his people independent from the Han Chinese in the religious sphere as well. He therefore chose a blend of the Indian, northern Chinese, and Tocharian/Khotanese forms of Buddhism, expanded to include Tengrian aspects. The persecution of Buddhism in northern China was reminiscent enough of the persecution of Manichaeism in Sogdia to convince him to follow the Tocharian Buddhist and Manichaean Sogdian examples in Turfan. He therefore established a translation bureau in his capital in Mongolia to render Buddhist texts into a uniquely Central Asian form.

To be consistent with the secular sphere and establish a unified high culture for his people, the Qaghan wished to use Sogdian for religious purposes as well. However, Buddhist texts in the Sogdian language did not exist at the time. The Sogdians were increasingly relying on the Chinese versions for their own personal use. If the Qaghan could not have Buddhist texts in the Sogdian language and if using the new Tocharian translations would only lead to the further complication of his people having to learn yet another foreign tongue, the only feasible solution for establishing cultural unity was to have Buddhist texts in the Old Turk language, but written in the Sogdian secular script. Therefore, he invited more Sogdians to Mongolia and asked them to adapt their alphabet to the specific needs of the project and help the refugee Han Chinese monks at the translation bureau accomplish this task.

The Gandhari master, Jinagupta, who had come with the Han Chinese and initially headed the bureau, could easily appreciate the Qaghan’s decision, having previously had long experience in Khotan and thus not being attached to strict Han Chinese forms. The Old Turk translations, then, blended Indian, northern Chinese and Tocharian/Khotanese Buddhist elements with aspects of Tengrism, as the Qaghan had wished. The project was so successful, Buddhism soon became popular among ordinary people and even the soldiers of the Eastern Turk realm.

Analysis and Summary

A common feature of Central Asian history is founders of new dynasties adopting a well-established, well-organized foreign religion as the official state creed in order to unify their people. This most frequently happened when their native religious traditions either were totally decentralized or were headed by influential conservative factions opposed to the new rule. The foreign power whose religion they adopted, however, could not be too strong, otherwise the new dynasty faced the threat of losing its identity and independence.

The Eastern Turks thus turned to the Sogdians, and not to the Han Chinese, to help them unify their empire. Another reason for this choice was undoubtedly that the urban Sogdian merchants had explained to the nomadic Turks of the steppes the significance of the Silk Route territory they had conquered and had convinced them of its importance. The Turk rulers quickly realized that integration with the Sogdians would be of great economic benefit to themselves.

Furthermore, although the main religion of the Sogdians was Manichaeism, not Buddhism, the Eastern Turks turned to the latter, not the former, as their unifying religion. This was probably because, despite the temporary setback of Buddhism in northern Han China during the 570s, Buddhism was the strongest religion of the area at the time.

The wisdom of the Eastern Turk choice of new religions was reinforced when, in 589, Wendi (Wen-ti), the founder of the Sui (Sui) Dynasty, succeeded in reunifying Han China by rallying victory behind the banner of Buddhism. The Indian religion had thereby demonstrated its supernatural power in fortifying yet another new dynastic house. The Turks’ wisdom in deciding to practice this religion in their own language and in the Sogdian script was likewise reconfirmed as they managed not to be consumed in the Sui military rally across northern Han China.

When Tonyuquq convinced the Second Eastern Turk qaghans more than a hundred years later to drop Buddhism and return to the customs and practices of Tengrism and the Turkic shamanic tradition, the main reason was that Buddhism had proved itself weak by permitting Tang China to end the First Eastern Turk Dynasty in the 630s. Success in providing transcendental power for military and political gain, then, appears to have been the main criterion used by the Turks and by other later Turkic and Mongolian peoples for choosing a religion.