Introduction

Before the demolition of monasteries and monastic life in Mongolia in 1937, Mongolian lamas were trained to a high level in Buddhist philosophy or in other branches of Buddhist sciences countrywide in several monastic universities, where they took the highest exams in their fields of studies. Numerous Mongolian lamas wrote their works in Tibetan on various topics within these fields, including many important commentaries on root texts. Others carried out the duties of different ranks in the monastic assemblies, while others who lacked this level of talent or perseverance lived the everyday monastic life performing the rituals during chanting sessions and attending to different monastic duties.

Monastic Administration, Ranks and Duties

The monasteries were led by the head, usually bearing the title khamba, abbot (Mong. qambu, Tib. mkhan-po), tsorj, Dharma master (Mong. čorǰi, Tib. chos-rje), or lowon, master or chief teacher (Mong. lobon, Tib. slob-dpon, Skt. ācārya). Individual temples and even temple complexes were led by the tergüün, head (Mong. terigün), who could also bear the title khamba, abbot. In datsans (Mong. dačang, Tib. grwa-tshang), monastic colleges, the head was called shunlaiw, scholar (Mong. šunglayiba, Tib. gzhung-lugs-pa; “follower of the scriptural system”). Other important ranks were that of the gesgüi, disciplinarian master (Mong. gesgüi, Tib. dge-bskyos) and the unzad, chant master (Mong. umǰad, Tib. dbu-mdzad, “lead chanter”). There were two or four disciplinarian masters and two or four chant masters in the main assembly hall and usually two of each in the other temples.

As for the tasks these title holders carry out, the unzad leads the chanting, being very skilled in the melodies and method of chanting and well-versed in all the texts that are used in all the ceremonies held in their monastery, temple or monastic college. The gesgüi is responsible for keeping order in every aspect of monastic life in the temple, maintaining order during the ceremonies and carrying out punishments if necessary. The tsorj and lowon both have important roles in special events or ceremonies, where they perform specific ceremonial tasks or conduct the meditation practices necessary for performing the rituals.

Gergen / gyargan, teacher (Mong. gerγan, Tib. dge-rgan) was a title for elderly honored teachers. In every temple, the chombon / chodwon / chowombo, offering master (Mong. čombon / čodbon / čobombu, Tib. mchod-dpon), together with the takhilch, offering assistant (Mong. takilči, Tib. mchod-pa-po; “preparer of the offerings”), was responsible for the preparation and proper arrangement of the offerings. The assistants of the chant masters were the golch, chanters (Mong. γoolči), called in Mongolian literally as “central ones” after the fact that they sat in the innermost row of lama benches in line with those holding higher ranks, thus occupying central seats. They took a leading part in the recitations.

Geyeg, disciplinarian assistants (Mong. geyüg, Tib. dge-g.yog; “servant of virtue”) helped with the activities of the disciplinarian masters (gesgüi), while the duganch, shrine keepers or shrine caretakers (Mong. duγangči, Tib. ’du-khang-pa) were responsible for keeping the temples clean, ensuring that the proper ritual accessories were ready when needed and distributing books and accessories during the ceremonies.

These ranks in the assemblies, such as abbot, Dharma master, teaching master, disciplinarian master, chant master, offering master, etc., are the same as in Tibetan monasteries and thus the Tibetan terms themselves are used in Mongolian for most of them.

There are different words used in Mongolian for monastics or monks. Of all of them, the word lam, “lama” (Mong. lam-a / blam-a, Tib. bla-ma) is the most generally used one and its meaning is, in general, different from its Tibetan meaning. Thus, it refers to any member of the monastic assembly, of any age, level of vows, or rank. The term emegtei lam, “female lama” (Mong. emegtei lam-a / blam-a) is its related term, used for female members of the monastic community. There is also the Tibetan origin term ani (Mong. ani, Tib. a-ne / a-ni) in use for nuns and khandmaa (Mong. qangdum-a, Tib. mkha’-’gro-ma, Skt. ḍākiṇī) for female practitioners. While lam is of Tibetan origin, khuwrag (Mong. quvaraγ / qubaraγ) is a Uighur-origin term. This is a more elegant or honorific term, though it can be used for young monastic students, as well as generally for any member of the monastic assembly. The term toin (Mong. toyin), again for monks, is also of Uighur origin and is rarely used today. There is also a term, bandi (Mong. bandi), used only for young novices.

In a limited number of larger monasteries there was an oracle who, in trance, channeled the pronouncements of the choijin, Dharma protectors (Mong. čoyiǰung, Tib. chos-skyong, Skt. dharmapāla) who occupied their bodies (Khal. Choijin buukh, Mong. čoyiǰung baγuqu; “descending of the Dharma protector”) for this purpose at these rituals. These oracles were called choijin, the same as the term used for the protectors themselves or might have also been called gürtenbe / gürtemb, medium (Mong. gürtenbe, Tib. sku-rten-pa; “body support”). Monasteries with an oracle had a great reputation.

There were also different administrative duties in the monasteries. Administrators with the ranks zaisan, official (Mong. ǰayisang), daamal, manager, supervisor (Mong. daγamal) or demch, monastic supervisor, caretaker (Mong. demči) belonged only to the large monasteries, while the smaller ones might have had only a nyaraw, bursar, treasurer, stockkeeper (Mong. nirba, Tib. gnyer-pa) to deal with the property of the monastery.

Apart from the above main ranks and duties in the assemblies, there were many other occupations among the lamas. For example, there were burkhanch, artists (Mong. burqanči; “one making buddhas”) and uran bicheech, calligraphers (Mong. uran bičigeči) trained in uran bichleg, the art of calligraphy (Mong. uran bičilg-e). Some lamas performed ordinary tasks such as anchin, hunter (Mong. angči(n)), while some collected and dried herbs for healing purposes or to prepare arts, incense (Mong. arča; juniper). Others followed their interests and thus there were, for example, lamas using different types of prognostication techniques, such as using shoo dice (Mong. šo, Tib. sho), erkh, rosary (Mong. erike), nom, book (Mong. nom), dal, scapula (Mong. dalu), or shagai, ankle bone (Mong. šiγai / šaγai).

All the main ranks and administrative duties are the same in larger temples today (2023), according to size, number of lamas and possibilities. Thus, all temples have a head or abbot and at least one chant master and one disciplinary master, while the other ranks are filled only in much larger assemblies.

Ceremonies and Ritual Life

Apart from the daily chantings and the different monthly rituals on the saryn düitsen / düichin, monthly “great days” (Mong. sara-yin düyičen, Tib. dus-chen) – namely, distinguished days of the lunar month with the individual temples and monastic colleges within a monastery having different specialized rituals on those days − jiliin düitsen / düichin, annual festivals (Mong. ǰil-ün düyičen) were also held. These were the biggest and most spectacular events and the busiest days in the life of a monastery, some with a long preparation period and connected meditational practices. Some were festivals held in all traditions of Buddhism, such as those celebrating the events of Buddha’s life; some were the special rituals of Tibetan Buddhism solely, for example the anniversary of Tsongkhapa’s death; and again, others were new installments in only the Mongolian form of Buddhism.

Tsam, ritual dance (Mong. čam, Tib. ’cham(s)) was performed as one of the biggest festivals in only the larger monasteries – namely, in about one-fifth of the around 1,000 monasteries of Mongolia. They were held on different dates and scales, with different types of tsam performed following different traditions or rules (deg, Mong. dig, Tib. sgrig). Of the different types, it was the tradition of the tsam dance of Tashilhunpo monastery that came to Mongolia at the beginning of the 19th century. It became known and popular there as the Jakhar tsam, Iron Palace Dance (Mong. ǰaqar, Tib. lcags-mkhar), named after the iron palace of the Lord of Death, Yama (Khal. Erleg nomun khaan or Choijoo). It was also known as Khüree tsam, the “tsam where dancers move in a circle” or the “tsam from the monastic city, Ikh Khüree” (Mong. küriyen / küriye čam), Choijoogiin tsam or Erleg nomon khaany tsam, “the tsam dance of Yama” (Mong. čoyiǰil-un čam, erlig nom-un qaγan-un čam), or Khangalyn tsam and Dogshidyn tsam, “the tsam dance of the fierce ones” (Mong. qangγal-un čam, doγsid-un čam), these later referring to the fact that in this type of tsam other wrathful protectors also appear. These Mongolian tsam dances even had their own tsamig handbook (Tib. ’chams-yig) written by the twelfth abbot of Ikh Khüree, Agwaankhaidaw or Agwaanluwsankhaidaw (Tib. ngag-dbang blo-bzang mkhas-’grub, 1779–1838).

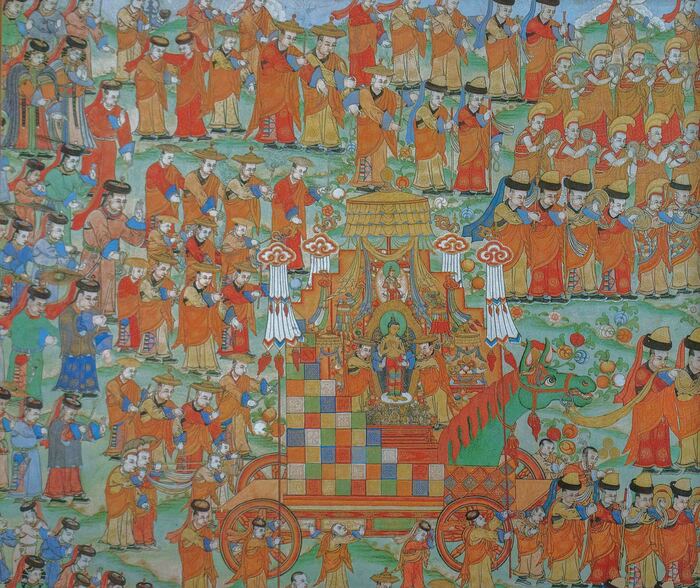

As for the other annual rituals, at the Maidar ergekh, Maitreya circumambulation (Mong. maidari ergikü), the statue of Maitreya, the future Buddha, was carried in circumambulation in almost every monastery, usually in the spring on the 16th of the first spring month or in the autumn, with a different tsam dance called Maidariin tsam, Maitreya dance (Mong. maidari-yin čam) held in many cases on the same day. The lamas circumambulated the monastery, followed by all the gathered laypeople, with the statue of Maitreya placed on a cart with a green horse head. In some Tibetan and especially Inner-Mongolian monasteries a white elephant is used instead. The accompanying ritual was called Jambiin chogo, “ceremony held in honor of Maitreya” (Tib. byams-pa’i cho-ga), and the accompanying recitations were made at the four main directions on the encircling road (goroo or gorlom). These were done to ensure rebirth in the Tüshid or Tögs bayasgalant oron, Tushita Heaven (Mong. tüšid, tegüs bayasqulang-tu oron, Tib. dga’-ldan), where the bodhisattva Maitreya is presently residing before coming to this world as the next Buddha, and to ensure the future meeting with his teachings.

During the Ganjuur ergekh, Kangyur circumambulation (Mong. γanǰuur ergikü), the volumes of the Kangyur (Khal. Ganjuur, Mong. γanǰuur) and other sacred books were also carried in circumambulation. This was celebrated in most monasteries also annually, sometimes on camel carts and sometimes carried by people. In some cases, the circumambulation took place around the given monastery or monastic city for a day, and in some cases the circumambulation circled the entire khoshuu, “banner, battalion, administrative unit” (Mong. qosiγu(n)), thus lasting for about a month. Other monasteries held their circumambulations at different schedules, for example the lamas of Zaya gegeenii khüree made the circumambulation around Bulgan mountain situated to the north of their monastery carrying the volumes of the Kangyur on the 15th day of each month.

Among the other important annual rituals were the ceremonies held at the end of the year. These included the three-day long khuuchin khural, “old ceremonies” (Mong. qaγučin qural), being the last ceremonies of the year, held on the 27th to the 29th of the last winter month. They included sor zalakh ritual (Mong. sor ǰalaqu, Tib. zor-’phreng), the ritual burning of the pyramidal sacrificial cake and structure, and the tsedor lkham ritual (Tib. tshes-gtor lha-mo) “the annual ritual cake offering to Śrīdevī” (Khal. (Baldan) lkham, Mong. lham, Tib. (dpal-ldan) lha-mo) on New-Year’s Eve.

The Lunar New Year started in monasteries with the first of the burkhan bagshiin dörwön ikh düitsen ödör, “the four great festival days of Buddha” (Mong. burqan baγši-yin dörben yeke čoγa, Tib. sangs-rgyas-kyi dus-chen bzhi / khyad-par-gyi dus-chen bzhi; “the four special festivals”). This was the fifteen-day oroin yerööl or ikh yerööl, Great Prayer Festival (Mong. oroi-yin irügel < irüger or yeke irügel < irüger, Tib. smon-lam chen-mo) or choinpürel molom yerööl, “prayers for showing miracles” (Tib. chos-’phrul smon-lam) held from the 1st through the 15th of the first month to commemorate Buddha’s defeat of six non-Buddhist challengers by mysterious methods that included performing miracles for 15 days.

As for the other three annual great festival days of the Buddha that were also celebrated and still are in every monastery:

- The 15th or full moon day of the first summer month celebrates three events of Buddha’s life – his birth, his enlightenment and his passing away

- The 4th of the last summer month celebrates Buddha’s first teaching the Dharma, the “first turning of the wheel of Dharma”

- The 22nd of the last autumn month celebrates Buddha’s “descent from the god realms.”

On all the above occasions, a special ceremony in honor of the Buddha, called Tüwiin chogo, “the ceremony of Buddha” (Tib. thub-pa’i cho-ga) or Burkhan bagshiin chogo (Mong. burqan baγši-yin čoγa), was held in the larger monasteries. Both tüwpa, the Able One (Tib. thub-pa, Skt. muni) and the Mongolian burkhan bagsh, “Buddha master,” are names for Shakyamuni Buddha.

On the 25th of the first winter month, the anniversary of the death of Tsongkhapa, or, as the Mongolians name him, Bogd Zonkhow (Mong. boγda zongqaba, Tib. tsong-kha-pa), was celebrated almost everywhere, as the majority of monasteries were Gelug ones. This festival was called Zonkhowyn düitsen, “the great day of Tsongkhapa” (Mong. zongqaba-yin düyičen, Tib. tsong-kha-pa’i dus-chen) or Zuliin khorin tawan, “the 25th offering of butter lamps” (Mong. ǰula-yin qorin tabun, Tib. (dga’-ldan) lnga-mchod; “offerings of the (twenty-)fifth (at Ganden)”). The tradition is, in the evening, to light hundreds and thousands of butter lamps and lights outside in honor of Tsongkhapa and to recite the short four- or five-lined Migzem (Mong. migǰem, Tib. dmigs-brtse-ma, short for dmigs-med brtse-ba; “non-referential loving kindness”) prayer to Tsongkhapa many times. The ceremony held on that day is known as Bogd lamiin chogo, “the ceremony of the Lama Master” (Mong. boγda lam-a / blam-a-yin čoγa), Bogd lam being also a Mongolian name for Tsongkhapa. It is also called Bogd Zonkhow lamiin chogo, “the ceremony of Tsongkhapa” (Mong. boγda zongqaba lam-a / blam-a-yin čoγa, Tib. tsong-kha-pa’i cho-ga).

Before the 1937 purges, almost every monastery in Mongolia had a considerable number of fully ordained lamas, gelen (Mong. gelüng, Tib. dge-slong, Skt. bhikṣu), and therefore almost every monastery held the 45-day Khailen or Yar khailen summer retreat (Mong. (yar) qayilan, Tib. (dbyar) khas-len); “(summer) commitments”) to strengthen the vows of lamas and to amend downfalls. Nowadays (2023), due to the small number of fully ordained lamas, the summer retreat is not often held in Mongolian monasteries. Meditational fastings (Mong. nünnei / nügnee, Tib. smyung-gnas) were also held in almost every monastery.

As the monastic colleges focused on specialized training, some of their monthly and annual rituals were connected to exams and other important events, therefore they had a remarkably varied ceremonial system in the monasteries.

Most of these rituals were the same as the Tibetan Buddhist ones or only modified in their details or the texts recited during them, but Mongolian Buddhism had special annual ceremonies as well. For example, on the 14th of the first spring month, Öndör Gegeenii ikh düitsen ödör, the Great Day of Öndör Gegeen (Zanabazar) (Mong. öndür gegen < gegegen-ün yeke düyičen edür), the ceremony called Dawkhar yerööl, “double prayer” (Mong. dabqur irügel / irüger), is held, which commemorates Öndör Gegeen’s death. It is called “double” as it coincides with one of the Ikh yerööl or Oroin yerööl, “Great Prayer” days (Mong. oroi-yin irügel < irüger or yeke irügel < irüger, Tib. smon-lam chen-mo).

Daily Life in the Monasteries

Apart from the annual ceremonies, there were also monthly rituals and other rituals specific to individual temples or colleges. On all other days, when there were no great festivals or ceremonies, lamas carried out daily life, busy with performing the daily rituals and chantings and with studying or carrying out their own duties. Rituals and studies started early in the morning. Lamas drank their manj / manz, “tea for the assembly” (Mong. manǰa, Tib. mang-ja), a salted milk tea that was the same as the traditional Mongolian drink, süütei tsai (Mong. sün-tei čai), and ate their daily food, tsaw, “hot meal” (Mong. čab, Tib. tsha-ba) in the breaks during the rituals. In the afternoon, some temples had another ceremony or lamas studied at their dwellings.

Monks knew the Tibetan script better than the Mongolian one. It was taught to them in priority to enable them to start memorizing the texts as early as possible and follow the chantings. The majority of the monasteries possessed the volumes of the Tibetan Kangyur and Tengyur, others had only a smaller library with the necessary texts. These ceremonial texts were mostly in Tibetan, but the Mongol bichig, the classical Mongolian or Uighur-Mongolian script (Mong. mongγol bičig) was also taught. The balance sheets and financial reports of monasteries were kept and written in classical Mongolian. Sometimes it also happened that they were in Mongolian language but written down in Tibetan letters. This also indicates that Tibetan writing was easier for most of the lamas. Unfortunately, at the destruction of the monasteries, these, together with the Tibetan sutras, were almost all burnt, but today archives keep such remaining texts as important documentation of the old monastic life.

The temple buildings were not heated, only the yurts were. This was due to the lack of firewood and to the fact that the usually large temples would have been impossible to heat using argal’, dried cow dung (Mong. arγal), which was and is still widely used in yurts. Therefore, in winter, ceremonies were held in yurts put up beside the temple buildings. One can meet such winter yurt temples in monasteries even today. Zul, butter lamps (Mong. ǰula) and denlüü, lanterns (Mong. denglüü, Chin. deēng long) were used for lightning.

Usually, several lamas, often relatives, lived together in a yurt, or a well-off lama could live in one on his own. It was usual for disciples to live together with their master and do all the housework for him, such as serving and cooking. For such work, the term togoo barikh, literally “to hold the pot” (Mong. toγoγan bariqu) was used, which meant not only cooking but also running the household and serving someone.

Interactions and Connections with Other Monasteries and Local Lay People

When monasteries were the only settlements in the country, the larger monasteries were at the same time also administrative centers of the state. Many were originally founded as residences for nobles. Consequently, monasteries, being settlements with lama residents, laypeople’s quarters and Chinese merchants nearby, played an important role in people’s lives. The monasteries and their lamas had different interactions and contacts with the local people, who either visited the temples from time to time or merely settled around the larger monasteries. Small temples, especially places for meditation built in remote sites, were only rarely visited by anyone.

The lay population did not reside in the monastic area itself but rather in the areas surrounding the monasteries. Poor families and beggars also could live nearby, mainly around the largest monastic cities. According to the monastic rules of celibacy, lamas were forbidden to establish any relationships with women. Those lamas who were interested in women or who had a wife could not live in the monastery but moved back to their families in the countryside. Nevertheless, they still came to the monasteries to attend the ceremonies either every day or just for the bigger ceremonies. Devotees often visited the monasteries for pilgrimage and worship, or for visiting their sons, brothers or other relatives who were members of the community there. The monasteries were operating partly from their donations. These donations included brick tea, dairy products, livestock, silk, juniper, flour, wheat, and so on.

Monasteries had livestock, meaning the so-called tawan khoshuu mal, five kinds of livestock of the Mongolians (Mong. tabun qosiγun mal) – horse, cattle, camel, sheep, and goat. The livestock were herded in remote pastures, with the herds and flocks of the different individual temples of a monastery usually herded separately at different sites. Some monasteries had tarialan, agricultural fields (Mong. tariyalang) cultivated by the Chinese or the Mongols and also forests for wood as building material and for renovation purposes.

There were connections between monasteries situated close to each other or in the same administrative area. In many cases, lamas visited each other’s monasteries or came for specialized studies for a period. Furthermore, there was a central monastery in every khoshuu, which was the biggest of the area, with other monasteries subordinated to it. The khoshuuny noyon, lord of the banner (Mong. qosiγun-un noyan) organized a naadam festival (Mong. naγadum) annually, with the three kinds of traditional games, which was of great importance for the lamas as well as laypeople.

Lamas occasionally came from Tibetan monasteries or mainly from Bogdyn Khüree, the monastic capital (Mong. boγda-yin küriyen / küriye) for some days or for longer periods to give wan empowerments (Mong. wang, Tib. dbang, Skt. abhiṣeka), lün oral transmissions (Mong. lung, Tib. lung, Skt. āgama), and teachings in certain monasteries. For these occasions, huge crowds gathered, usually from other monasteries in the area. Tibetan resident lamas also lived in a very few monasteries. Mongolian lamas also went to different Tibetan monasteries to pursue their advanced studies, especially to the three main Gelug monasteries of Tibet, Drepung and its Gomang college (Khal. drepung goman, Mong. drepung γoman, Tib. ’bras-spungs sgo-mang), Ganden (Khal. Gandan, Mong. γangdan / γangdang, Tib. dga’-ldan), Sera and its Je college (Khal. ser je / sera je, Mong. sera ǰe, Tib. se-ra byes), and also to Tashilhunpo (Khal. dashlhünb / dashlhümbe, Mong. taš(i)lhunb / taš(i)lhümb, Tib. bkra-shis lhun-po). Badarchin, itinerant lamas (Mong. badirči(n)) wandered huge areas for pilgrimage, collecting alms. They always stopped by monasteries as did wandering zoch tantric masters or practitioners who, for periods, also stopped by monastic complexes and held their ceremonies nearby.

There were Chinese settlements near larger monastery sites, as mostly Chinese operated the baayuu (Mong. bayuu, Chin. wă yáo), kilns where bricks were fired, and Chinese workers took part in monastery construction, and the carving and decoration of the temples, and also because of commercial purposes. Chinese merchants wandered the countryside mostly by caravans and stopped by monasteries to sell their products. At the larger sites, there were püüs or püüz, Chinese stores (Mong. püüǰe or püüse(li), Chin. pù zi (li)) in permanent places where animal products, such as wool and leather, were bought from Mongolians, and other products like tea, silk, flour, and candies, were sold to them. They exchanged articles or used brick tea as a means of payment. Later, Chinese, Russian, and other coins and money also were used as exchange.

Highly organized caravan routes with örtöö, relay stations (Mong. örtege(n)) every 30 kilometers crossed the country. Some caravans and örtöös were operated by a given monastery or by their shaw’, subordinated people (Mong. šabi). Russian merchants also wandered the country and stopped by monasteries.