Introduction

Buddhism was still flourishing in Mongolia even at the beginning of the 20th century. But between 1937 and 1939, Stalinist forces destroyed all the monasteries, with the exception of several temple buildings that remained partly intact, killed masses of lamas, and jailed or forced the surviving ones to return to secular life. This put an end to monasticism and the practice of Buddhism in Mongolia for decades.

There had been more than 1,000 monasteries and temples in the area of today’s outer Mongolia and the number of lamas was supposedly around 80,000. Among them, the monastic capital – known as Ikh Khüree (Mong. yeke küriyen / küriye), the Great Monastic City, or Bogdyn Khüree (Mong. boγda-yin küriyen / küriye), the Monastic City of the Bogdo Gegen – had about 100 individual temples, or assemblies, and monastic colleges in its two monastic districts. These two were Gandan (Mong. γangdang, Tib. dga’-ldan) and Züün khüree (Mong. ǰegün küriyen / küriye; literally meaning “eastern monastery” as it was the eastern one of the two).

Monasteries were the only settlements in the country and their temples were the only fixed buildings in the land of nomadic yurts. Not only religious activities but also all state administrative activities were executed in the monastic complexes since they also functioned as administrative centers and housed the lay population around them in separate districts. There were also smaller monasteries and temples, some situated far away from inhabited places, often only temporarily holding ceremonies. These were located in fixed places in relation to where the nomadic herding families moved four times a year.

Monasteries were the only places for education. Thus, the many branches of the sciences – like Tibetan and Mongolian writing, grammar, literature, poetry, philosophy, mathematics, astrology, and even medicine – were practiced and taught only in them.

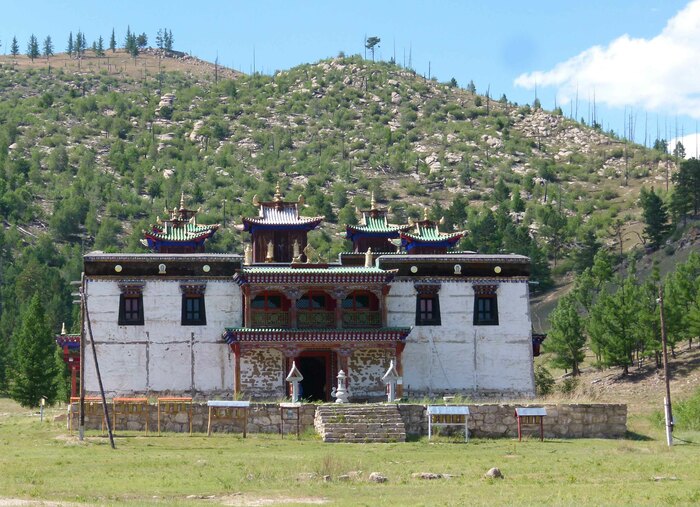

Monastic sites differed not only in their size and the number of their lamas, but also in the circumstances of their foundation, architectural features, and styles, many of which differed from the Tibetan forms. There were also local variations, with several types of building materials and arrangement or layout.

The Monastery and Its Environment – Sacred Places, Peaks and Waters

Though Tibetan sache, geomancy texts (Tib. sa-dpyad; “inspection of [the suitability of] land”) describe the signs that render sites suitable for founding a monastery and the way to choose such a site, in fact different factors were also considered. In the harsh Mongolian circumstances, in most cases the basic necessities had to be taken into consideration in order to establish a monastery or temple with thousands, hundreds or even a few resident lamas. Thus, monasteries were set up on sites where water was plentiful, which could be from rivers, creeks, or wells. If the landscape features made it possible, monasteries were founded in the foreground of hills or mountains that were situated to the north of the site or surrounding it, thus protecting them from the strong wind coming from the northwest. In the Gobi area and in areas with similar harsh conditions, this meant they could be founded only on the plains of the Gobi or on the Mongolian steppe where there was a well or some other source of water.

Small meditational retreat temples were built, however, on remote mountain peaks – for example, Töwkhön monastery (Mong. Tobqan, Tib. sgrub-khang; “meditation hall”) in Öwörkhangai province, Bat-Ölzii. Some were also built in hidden valleys, thus providing peaceful conditions for lamas meditating and practicing there. Apart from landscape features and availability of water, other circumstances such as trading routes and the network of relay stations also determined the planning and setting up of monastery sites.

The lama community had a special relationship with the monastery environment, maintained through rituals related to the sacred places, peaks, or waters around it, in which offerings were made to their local spirits. The surrounding hills and mountains were honored and, as such, were often called by the name khairkhan (Mong. qayirqan), literally meaning “gracious” but also used in the meaning of uul, mountain (Mong. aγula(an)). On their peaks, owoos, cairns, stone heaps (Mong. oboγ-a, Tib. la-rtse / lab-rtse / la-btsas) or sometimes wooden structures for the veneration of local spirits were erected. The monastery’s lamas would venerate one or more of these takhilgat owoos, “owoo where offerings are performed” (Mong. takilγ-a-tai oboγ-a), by conducting rituals for the gazryn ezen, local spirits, or sawdag, “earth lords” (Mong. γaǰar-un eǰen, sabdaγ, Tib. sa-bdag). These owoo venerations, called owoo takhilga (Mong. oboγ-a takilγ-a), took place annually and often including the traditional eriin gurwan naadam, “three manly games” (Mong. er-e-yin γurban naγadum) – horse racing, wrestling and archery. Therefore, were also called owoony naadam, “owoo games” (Mong. oboγ-a-yin naγadum). Masses of people gathered from around the monastery’s area for these games.

Owoos were and still are erected usually near different spectacular natural formations, such as at passes, crossroads, fords of rivers, spectacular rock formations, solitary rocks, gants mod solitary standing trees (Mong. γanča / γaγča modun), and springs. They are also found next to various sacred places, such as bulsh or kheregsüür, ancient burial places of the old nomadic empires from Bronze Age to Turkic (Mong. bulasi, keregsür), stone monuments, the so called “deer stones” of old civilizations, and also near destroyed Buddhist monastic sites.

The cult of owoos originates from the shamanic folk religion of the Mongols and is in connection with the veneration of local spirits, the cult of mountains and, as related to this, the veneration of ancestors. Later, owoo venerations were adapted and incorporated into Buddhist rituals as were other aspects of folk religion. The offerings that are placed at owoos also changed accordingly. Apart from stones, balin offering cakes (Mong. baling, Tib. gtor-ma), incense, sweets, dried curds, tea, khadag silken ceremonial scarfs (Mong. qadaγ, Tib. kha-btags), and prayer flags are placed on them as offerings. We also often find animal skulls on certain types of them placed by local herders. In the old times, animal sacrifices were also performed, but that changed with Buddhism and sacrifices were replaced by the tradition of seter, “freeing lives (of animals)” (Mong. seter, Tib. tshe-thar), where an animal chosen from the stock is offered ritually to the local spirits, is adorned with a khadag and is then never killed for food. People often also place money and glasses of alcohol on owoos, though this is traditionally forbidden.

Owoos, like everything else related to religion, whether Buddhist or shamanist, were destroyed during the communist times and then re-erected after the religious revival. Since then, their veneration and the connected rituals have been restarted.

Owoos are of different types, with different rules of usage. There are:

- Owoos built in remote places where only annual rituals are held, such as at Lunar New Year or summer, with prohibitions on who can approach them and make offerings at them. These include (1) owoos of given clans or kin groups, venerated only by men of a given clan to ensure the well-being and safety of their clan and (2) owoos venerated by men nomadizing nearby and not necessarily from the same kin group.

- Owoos situated at mountain passes, dangerous roads, or crossroads where any passers-by, including women, can make offerings anytime to ensure safe travel and conciliate local spirits for blessings on their travel. Here, lorry drivers also place car components, or people their belongings such as clothing or shoes, or ill persons leave their accessories like crutches after their recovery.

- Owoos built for the well-being of animals, and on which horse and cow skulls, scapulas, and other parts of animals are placed as offerings.

- Some owoos can be approached only on foot.

Today (2023), at some owoos lamas perform the annual offerings, but there are also separate owoos used by shamans and these look a bit different. Buddhist owoos have a sorogshin, life-tree (Tib. srog-shing) as their central axis, similar to stūpas and Buddha statues, and Buddha-figures and scriptures buried at their base.

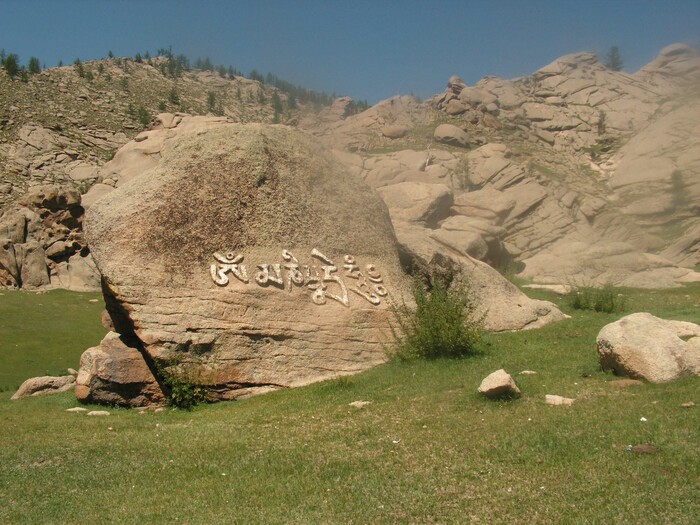

The owoos venerated annually by the lamas of a given monastery belonged to the type of owoos erected at remote places for the people of a given area. These are a different type from those for travelers situated by the roads. Tibetans have similar stone heaps or cairns as offering for the local spirits and “mani stone walls” built of stones with the OM MANI PADME HUM mantra of Avalokiteśvara on them, but the owoo cult of the Mongolians is different and bears the imprints of Mongolian folk religion.

Rashaan, holy springs or creeks (Mong. rasiyan, Skt. rasayāna), special rocks (for example uushai, human-shaped rocks), caves, peaks, and other isolated places where lamas held meditations for years were also venerated in the neighboring area. Such meditation caves later had small altars put up in them with offerings. Pictures of different Buddha-figures or masters were carved or painted on nearby rocks. Other rocks had maan’, Tibetan mantras (Mong. mani, Tib. sngags, Skt. mantra) carved on them. The Mongolian term is maant khad, from the Tibetan syllables ma-ni carved on them (Mong. mani-tai qada(n)). All these natural formations were believed to have their own local spirits.

The waters from these holy sites were used for preparing the different offerings and as takhilyn us, holy water as an offering (Mong. takil-un usun). In some cases, there were different wells for the lamas, called undanii us, “drinking water” (Mong. umdaγan-un usun), and it was usual to have a different well for animals. Some rituals, like the ceremonies for making dültsen, colored sand mandalas (Tib. rdul-tshon), were connected to the holy springs or rivers situated near the monastery. Upon the completion of these rituals, the sand mandala is destroyed, with the sand being taken in a ceremonial procession to the water where it is offered to the sawdag spirits of the land (Mong. sabdaγ, Tib. sa-bdag) and the lus, water spirits (Mong. luus, Tib. klu, Skt. nāga).

Meditation temples or hermitages, small zod, “cutting through” assemblies (Mong. ǰod, Tib. gcod) for practicing the chö system for cutting through ego-clinging, and temples for the veneration of lus water spirits (nāgas), called lusyn süm (Mong. luus-un süme), were built in remote places. Other monasteries were set up near roads to ensure that people could have easy access to them for making prostrations, visiting ceremonies and making donations for ensuring the long-term operation of the monastery or temple.

Types of Monastic Sites

The approximately 1,000 monasteries and temples at the time of the 1937 purges were very different from each other in terms of size, number of lamas, circumstances of their foundation, and layout arrangements. The various kinds of monastic sites ranged from large monastic centers of 1,000 to 2,000 lamas serving at the same time as centers of administrative divisions with settlements of laypeople beside them, through monasteries with hundreds or dozens of lamas, to temples serving people of a smaller area, or temples with temporary rituals only.

The old administrative divisions of Mongolia even at the beginning of the 20th century were totally different from those of today’s Mongolia (2023). In the old times, the area of the Khalkh, Khalkha Mongols (Mong. qalq-a), was divided into four large areas, the aimag, provinces (Mong. ayimaγ) of the four khan princes (Mong. qan). Today, there are 18 large and 3 smaller provinces, similarly called aimag, while Ulaanbaatar is an independent provincial municipality. The smaller divisions within the aimag are the sum, sub-provinces (Mong. sumun). The old aimag divisions were divided into smaller units called khoshuu, banner, battalion, administrative unit (Mong. qosiγu(n)), at the center of which was the khüree, monastic city (Mong. küriyen / küriye) of a worldly noble.

These monasteries, khüree, were often named after the given noble, including his Manchu origin title, such as:

- Khan, prince (Mong. qan)

- Noyon, lord (Mong. noyan)

- Wan, duke (Mong. wang, Chin. wáng)

- Beil / beel, Manchu title for third-grade princes (Mong. beyile)

- Beis / bees, Manchu title for fourth-grade princes (Mong. beyise)

- Gün, duke, Manchu title also for fourth-grade princes (Mong. güng, Chin. gong)

- Jasag, “lord of the banner” (Mong. ǰasaγ).

These aimag divisions and especially the khoshuu subdivisions within them had changed many times.

Monasteries serving as the seat of an incarnate lama, a tulku, also had great importance and these also were named after the given incarnate lama. These incarnate lamas bore various titles in Mongolian, such as:

- Khutagt, Khutugtu, Highly Realized One, Noble One (Mong. qutuγtu, transliterated in Tibetan as ho-thog-tu, Tib. ’phags-pa, Skt. ārya)

- Khuwilgaan, Khubilgan, Incarnate Lama (Mong. qubilγan, Tib. sprul-sku, Skt. nirmāṇakāya)

- Gegeen, Brilliant One (Mong. gegen < gegegen) or gegeenten (Mong. gegenten < gegegenten).

The largest monastic sites were always big centers in the given aimag and khoshuu, and in every khoshuu, apart from the central monastic city, there were further monasteries of different sizes. In the detailed monastic system, there were strong connections and well-defined subordinated relations between the different-sized monastic sites in the area of the same khoshuu.

Old Mongolian monastic sites from the 16th century till the beginning of the 20th century could be divided into the following categories according to their size:

- Khüree, monastic city (Mong. küriyen / küriye), serving as a large administrative center with about 800 to 2,000 lamas (with the old monastic capital housing 10,000 lamas) and numerous temples surrounded by the lama dwellings and, outside the monastery, by the districts of laypeople

- Khiid, monastery (Mong. keyid), with about 50 to 500 lamas and several temples, built sometimes also in remote places

- Süm or dugan, temple (Mong. süme, duγang, Tib. ’du-khang), with dozens of lamas

- Khural or jas, permanent or temporary assembly (Mong. qural, ǰisa) with only a few lamas and operating in one temple building being, mostly a yurt temple.

There were also several types of smaller assemblies:

- In some such small jas assemblies (also named as khural or süm), permanent ceremonies were held by a few lamas, while in other, temporary jas assemblies – which were guarded all year around usually by only one lama, a takhilch, preparer of offerings (Mong. takilči) or a sakhiul or manaach, guard (Mong. sakiγul, manaγači) – ceremonies were held only for some days, usually in the summer. They were conducted by numerous lamas coming for this purpose from the main monastery or the larger monasteries of the khoshuu and who, in summer, visited all of these small sites of their area.

- In some other temporary assemblies, tsagiin khural (Mong. čaγ-un qural, also named as tsagiin jas or tsagiin süm), lamas of the neighboring areas nomadizing with their own families only gathered at the great days to hold ceremonies.

- A special type of the smaller assemblies was the örtöö jas or örtöö khural (Mong. örtege(n) ǰisa or örtege(n) qural), which were established near örtöö, horse relay stations (Mong. örtege(n)), situated about 30 kilometres from each other on the route. Later, such temples were set up also along other main routes, such as Chinese trading routes.

- In some areas, there were small jas temples for every clan or tribe, called otog (Mong. otoγ), being the smallest units within the khoshuu. These temples were often named after the given otog name of the area.

- There were also small zod tantric temples called zodyn khural (Mong. ǰod-un qural), with many of them operating in a yurt, sometimes with a kitchen and other buildings put up beside it. These were permanent individual assemblies.

- In other cases, zod masters or zoch lam, chö lamas (Mong. ǰoči lam-a / blam-a, Tib. gcod-pa) lived near the large monastic complexes or at their borders, setting up their small white tents or their yurts and holding their zod rituals in them, perhaps with their few shaw’ disciple students (Mong. šabi; disciple). These rituals were more frequently called lüijin, “offering the body” (Mong. lüyiǰin, Tib. lus-sbyin) as a means to sever ego-clinging and concepts of solid existence. Sometimes, they even had their small permanent temples near the large monasteries.

- The most isolated temples were the hermitages, bearing also the name khiid. (Mong. keyed), with the term in this meaning being equivalent to Tib. dgon-pa, retreat temple, hermitage.

These names for monastery types were often included in Mongolian monastery names but were not unambiguous categories. Monasteries often had several name variants, perhaps with different monastery-type names included in them. Several of the above monastery types were unique for the conditions in Mongolia, such as the temples at relay stations or the many temporary assemblies. Also unique was the naming of monasteries after the local nobles or the head incarnate lamas, or after the administrative divisions, or even after the clans, although they all had traditional Tibetan names among their name variants as well. Large monasteries, however, did not differ much from the Tibetan ones in their main functions and training, only in their arrangements, architecture, and outer styles.

Monastery Types According to the Circumstances of Their Founding

Monasteries can also be categorized based on the circumstances of their founding. The following four types were described by A. M. Pozneev, who wrote a detailed description of Buddhism in Mongolia at the end of the 19th century:

- Gegeen or khutugtu monasteries, founded by the Khalkha Mongols as seats for different incarnate lamas, tulkus (gegeens, khutugtus or khubilgans)

- Manj khaany zarilgaar baiguulsan monasteries (Mong. manǰu qaγan-u ǰarliγ-iyar bayiγulugsan), called by Pozneev “emperor monasteries,” founded on Manchu order and maintained from the Manchu imperial treasury

- Khoshuu or sum monasteries (Mong. qosiγu(n), sumun), called by Pozneev khoshuun or sumun monasteries, founded by these administrative divisions or by Khalkha clans (otog)

- Monasteries founded by individuals, such as Mongolian nobles or princes.

Gegeen or Khutugtu Monasteries

Of these four types, the gegeen or khutugtu monasteries were the wealthiest due to the large šaw’ nar, subordiated areas (Mong. šabinar) associated with them. These areas were conferred by the founding nobles of the monastery, and they maintained the numerous lamas in them. In addition, due to the presence of the given Khutugtu, many devotees visited them and contributed to the wealth of these monasteries. As a consequence, many lamas resided in these khutugtu monasteries, and trade flourished nearby. The gegeen or khutugtu monasteries could also be of different sizes, thus consequently bearing the monastery-type names: khüree (monastic city), khiid (monastery) or süm (temple or shrine) in their names. Their residents, however, always resided in the monastery, and ceremonies were permanent as their operation was well funded.

Emperor Monasteries

In contrast, in many cases, the emperor monasteries – monasteries founded by the order of the Manchu emperor and funded from the Manchu imperial treasury – flourished only while funding was secured from the emperor. They became abandoned when this funding ceased, in which case the lamas left them, only returning for annual rituals. A main cause of this was that, although at their founding – mainly during the reigns of the Kangxi (Khal. Enx Amgalan, Mong. Engke amuγulang, 1663–1722) and Yongzheng (Khal. Nairalt Töw, Mong. Nayiral-tu töb, 1722–1735) Emperors – every khoshuu, on Manchu order, sent one lama each to the new monastery and paid his expenses from then on, nevertheless, in case of an outbreak of poverty in their home area, these lamas were no longer sent or supported by the different khoshuus. Usually, these lamas resided in yurts at these monasteries, therefore only some buildings remained from them after their lamas left.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, only those emperor monasteries that were founded on Manchu order for one of the khutugtus were operating. In the other emperor monasteries, only the great annual ceremonies were held.

Khoshuu, Sum and Otog Monasteries

The two main types of monasteries founded by individual parties or administrative divisions were the khoshuu and the sum monasteries. Respectively, these were the main monasteries of the larger administrative divisions or provinces and the smaller monasteries of the subdivisions or subprovinces. The khoshuu monasteries were numerous, as every khoshuu had one. During Pozneev’s time, this meant there were 86 such monasteries. These monasteries were always built, furnished and operated by the given khoshuu, with the income from ceremonies conducted by them contributing to their support. These monasteries were situated near or at the khoshuu center where the khoshuu noble’s residence and the khoshuu government buildings were located. Serving as large administrative centers as well, they received many visitors whose donations contributed to their well-being. Therefore, their operation was easily ensured.

Each of these larger monasteries had many lamas coming from the given khoshuu and settling in their own yurts by the monastery. The sum monasteries, on the other hand, were smaller assemblies of several small wooden temples situated at remote places on the steppe with 3 to 4 yurts around them. These were founded during the times of prosperity in the given sum with lamas from its area moving in and holding ceremonies. Their long-term maintenance, however, was not ensured, and therefore, over time, they became abandoned. Their lamas either left for larger gegeen or khoshuu monasteries, or some returned to their families nomadizing nearby, returning to the monastery and conducting occasional ceremonies on special great days.

The otog monasteries also belonged to this category, being monasteries of the smallest administrative divisions or clans within the sum and khoshuu divisions. Each otog might have its own temple in its area.

Monasteries Founded by Individual Nobles

The monasteries founded by individual nobles – the last of the four main types of monasteries – could also operate only so long as the noble founding them or his successors provided all the expenses of the lamas residing there and for the rituals. Otherwise, they also ceased operation and were abandoned. Many such monasteries went under the control of the sum monasteries. Thus, although they no longer had any residing lamas, lamas arrived at them from these sum monasteries at the annual great days.

As seen from the above, the circumstances of the founding of a monastery had a great impact on its long-term operation. Lamas of smaller monasteries usually left and later joined one of the khushuu or gegeen monasteries as they were more secure with a more frequent and better income. Life was happier and more eventful in them. The size of the monastery, number of its lamas and thus the possibilities of its operation had an effect on the ceremonial system as well. Many monasteries started with a large number of lamas but later became emptied with, ideally, ceremonies held on the annual great days with lamas who had already left the monastery gathering only for these occasions.

In addition to these above four types of monasteries, there were many other types of monasteries as well, as described above.

Time of Founding

The monastic sites that can be categorized as above were founded in different periods from the 16th century till the beginning of the 20th century. The main monastic cities were founded from the 16th to the 18th centuries, with the first monastery, Erdene zuu (Mong. Erdeni ǰuu, Öwörkhangai province, Kharkhorin, Mong. qaraqorum, near Karakorum, the ancient capital) founded by Awtai / Abtai sain khan (Mong. Abtayi sayin qan) in 1586 and Baruun khüree (Mong. baraγun küriyen / küriye, Öwörkhangai province, Kharkhorin) founded by Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar (Mong. öndür gegen < gegegen; The High Brilliant One) around 1650.

At the beginning of the 20th century there were still large and important monasteries being founded, such as for example several monasteries in Dundgow’, Delgertsogt, founded by Zawa Damdin Luwsandamdin (Mong. ǰaba damdin, Tib. (rtsa-ba) blo-bzang rta-mgrin, 1867–1937). Most of the small temporary jas temples were also founded then, though, as already seen, many of these had once been permanent operating temples.

Arrangement Types of Monastic Sites

Small assemblies operated in yurts or had only one or two small temples plus additional buildings. This was either because the residents were few in number or they were only temporary assemblies. However, larger monasteries in Mongolia had different special layout types depending on their size, function and other factors.

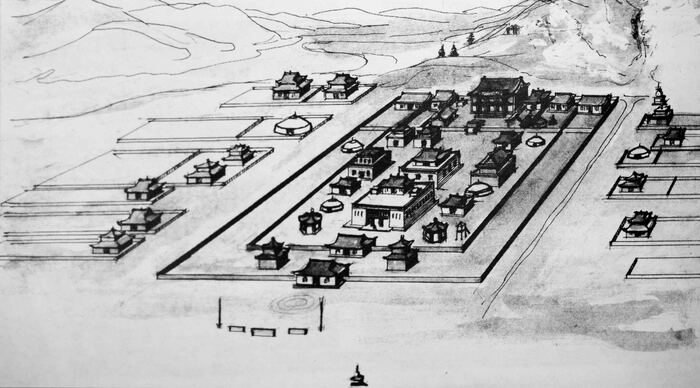

In general, the monasteries, their temples and other buildings as well as the courtyards faced to the south, as it is usual in Mongolia − even the yurts are put up accordingly. The tsigchin, main assembly hall (Mong. čoγčin, Tib. tshogs-chen) stood in the center, and other temples were built around it or perhaps in the same row. This later was the special arrangement for monasteries situated in the Gobi.

One special type of monastery founded on the order of the Manchu emperor consisted of a complex within walls, with even the lama dwellings situated inside, but otherwise this was not typical in Mongolia. A rare example of this arrangement is the partly intact Erdene zuu monastery, the walls of which consist of 108 stupas. These stupas remained intact and were renovated, as were several of its temple buildings. There are no remains, however, of the lama dwellings that were once also situated inside.

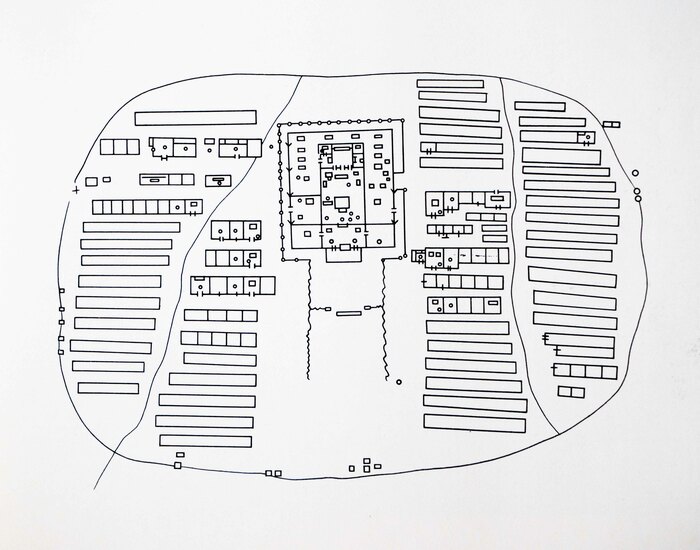

A more typical arrangement was where only the central part of the temple buildings was walled-off, and the lama dwelling districts (aimags) were situated outside, surrounding it. Some examples are:

- Amarbayasgalant monastery (Mong. Amurbayasqulang-tu) in Selenge province, Baruunbüren, left partly intact

- Dambadarjaa monastery (Mong. dambadarǰai, Tib. bstan-pa dar-rgyas) on the northern part of Ulaanbaatar with also some surviving temple buildings

- Dashchoinkhorlin monastery (Mong. dašičoyinqorling, Tib. bkra-shis chos-’khor gling), which once stood near Dambadarjaa monastery, to the north of it, but was completely ruined.

In other types of arrangements, even the central part was not walled off. The monastery stood in a zadgai, open area (Mong. ǰadaγai) with maybe some of the main temples individually fenced off. The material of the fences was similar to the material of the buildings in accord with what was available – stone, brick or mud.

Lamas lived in yurts, fenced-off small buildings or brick and mud cells, this latter being found mainly in the Gobi. In all the above cases, the lama dwellings stood in districts around the central part of temples in an upside-down U-shape facing to the south, in the so-called khüree deg, “arrangement in a circle” (Mong. küriyen / küriye dig). What was very characteristic is that all the aimag individual residential areas stood within separately fenced-off courtyards, and they all had their own temples surrounded by the dwellings. Lamas in an aimag all came from the same administrative division, with the word “aimag” itself originally meaning “province.” This is similar to the system in Tibetan monasteries where lamas live in different divisions called kangtsen (Tib. khang-tshan) and within them mitsen houses (Tib. mi-tshan), also according to the places of their origin.

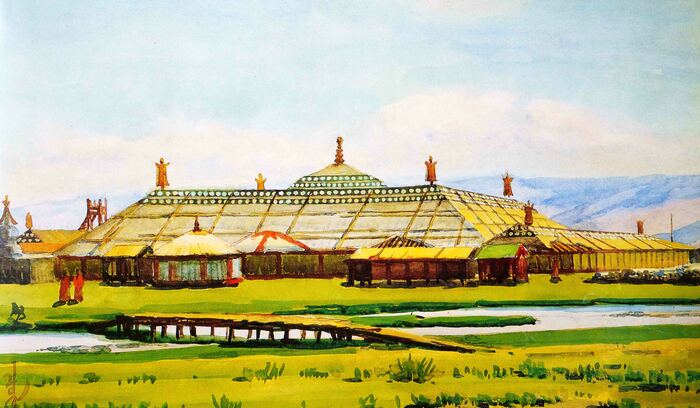

The lamas of the aimags gathered daily for ceremonies in their own aimag temples, except for those who belonged to one of the specialized monastic colleges of the monastery or to its main assembly hall, as these latter did not have their own residential districts or aimags. The best examples of khüree deg are the two distinct monastic districts of the old monastic capital with their main assembly halls and monastic colleges and other temples in the center, aimags and aimag temples around, and with the laypeople and merchant quarters on the outisde. Bereewen khiid (Khentii province, Ömnödelger), Lamyn gegeen monastery (Bayankhongor province), Daichin wangiin khüree (Bulgan province) and Khoshuu khiid (Dundgow’ province, Delgerkhangai) had the same arrangement as visible in old pictures or old paintings. In these, the temple buildings were not fenced off, but in Baruun khüree / Shakhyn khüree (Öwörkhangai province, Kharkhorin) and Zaya gegeenii khüree (Arkhangai province, Tsetserleg), for example, several of the temples were fenced off and surrounded by the aimags, also in the khüree deg arrangement.

In the Gobi area, instead of the khüree deg, two other arrangement types were typical. The temples stood in a row with the cells of lamas also in rows on the two sides and at the back. The other Gobi monastery arrangement type was again different. Here the temples stood in courtyards with the temples as well as the courtyard walls made of brick or mud and the brick cells or yurts of lamas were arranged in other conjoining and interconnected courtyards. Courtyards stood in rows, but the rows also were connected, as the courtyards were joined to each other often on each side with gates. Thus, these sites had a labyrinth-like arrangement.

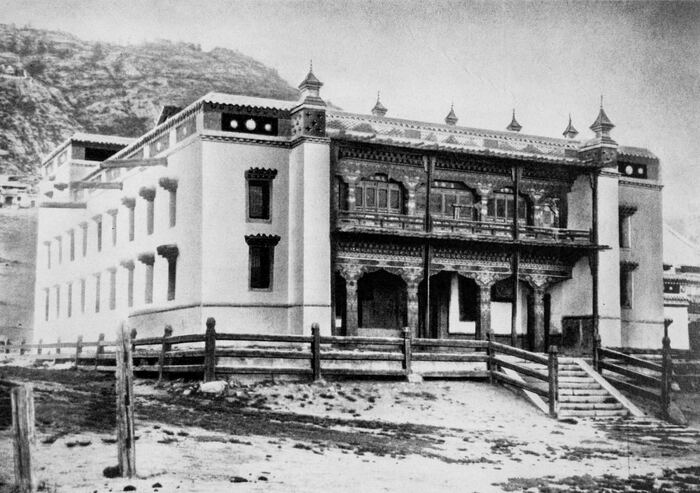

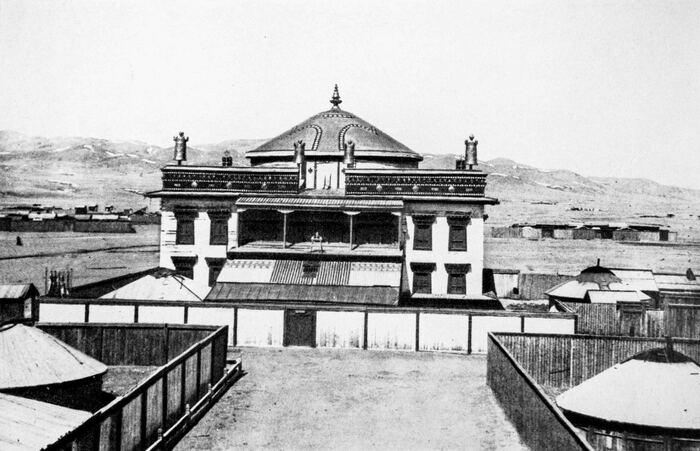

Architectural Styles

Mongolian monastery architecture used the Tibetan and Chinese styles and also combined them. Tibetan-style buildings were characterized by simplicity. Buildings had a flat roof, and the walls of the square-shaped buildings were trapezoidal, sloping outwards. The thick brick or stone walls were simply whitewashed, with the wooden beams, columns and window-frames characteristically painted reddish-brown. Temple buildings in Tibet originally could be three- or four-storied as well, with the stories built on top of each other in a terraced form with smaller and smaller stories, while in Mongolia they were usually only one- or two-storied. Windows were only on three sides of the buildings, with no windows on the north side, and they were placed relatively high. The wooden window frames also had a characteristic trapezoidal shape, being narrower at the top, and had nicely decorated windowsills. Buildings were decorated with friezes running around the top of the buildings under the roof, and with gilded symbols like the Dharma Wheel with gazelles, the victory banner and other symbolic decorations on the flat rooftops. Exclusively Tibetan-style temples were rare, however, in Mongolia.

The most characteristic feature of Chinese-style temples were the tiled tent-roofs with upward curving roof corners. On the south or entrance side, the roof protruded and thus a porch was added with wooden pillars holding the roof. The roof was often two-storied, with a smaller story at the top. Chinese-style temples were usually much lower than Tibetan-style ones. Chinese temples were richer in decorations. Roofs had gilded or green glazed tiles and were decorated with small, glazed sculptures of birds, animals, dragons, and mythical animals sitting at the edges of the roof. Columns and walls were painted in bright colors, red and yellow, and dragons were carved or painted on the columns and column-heads. Wooden doors were also painted in a reddish color. Monastery name plates above the entrance door were also characteristic, with the monastery name painted on the blue plates in golden letters in Manchu, Mongolian, Tibetan and Chinese. Often, on the two sides of the entrance two stone lions stood, as well as bronze or stone incense pots.

Chinese-style temples only had windows on the south or entrance side, with wooden bars on them. In front of the main entrance to the monastery, on the south, the yampai, protecting wall (Mong. yangpai, Chin. yĭng bì) stood with dragons painted on it, protecting against evil spirits. This basic Chinese temple style was, however, simplified and modified by the Mongols, for example by building two-story buildings and using less decorations.

A Tibetan-Chinese mixed style was also used. For example, the Tibetan-style building with simple white walls was completed with the characteristic Chinese-style roof. Glazed bricks were a characteristic element of Chinese-style architecture and were very decorative, but they were also used for mixed-style buildings where flat Tibetan-style roofs were replaced by tiled roofs. Usually, within a given monastery there were different Tibetan-, Chinese-, and mixed-style buildings. A characteristic example of this is the Gandan main monastery in Ulaanbaatar with Chinese-style gates, the mixed-style Migjid Janraiseg (Mong. ǰanrayisig, Tib. mig-’byed spyan-ras-gzigs, Skt. Avalokiteśvara) temple, and Chinese- and mixed-style temple buildings. The revived monastery now also has a recently built modern-style huge main assembly hall.

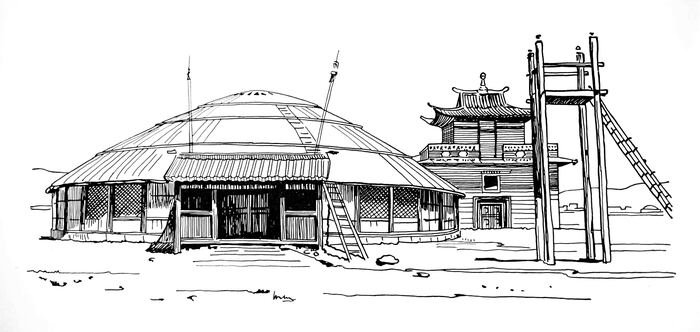

Apart from these significant styles, Mongolian monastery architecture developed its characteristic forms as well. For example, ger khelbert dugan, yurt-shaped wooden temple buildings (Mong. ger kelberitei duγang) were modelled on the traditional Mongolian dwelling, the felt-covered yurt. Yurt-shaped concrete or brick temples were also erected after the revival, following the same tradition. Hexagonal or octagonal wooden temples were another very characteristic type. A typical detail of both yurt-shaped and rectangular or polygonal wooden temple buildings was the gonkhon, protector house/chapel (Mong. γongqon, Tib. mgon-khang), a conjoined small chapel built at the north side of the temple building to house the images of the protectors of the temple and offerings.

Two additional characteristic Mongolian architectural forms must also be mentioned. One of these is a special type of main assembly hall, tsogchin dugan (Mong. čoγčin duγang, Tib. tshogs-chen ’du-khang) named after the main assembly hall of the old Ikh khüree, called Battsagaan, “Solid white” (Mong. batučaγan). It was named as such for being a white-colored, flat temple with a small and also flat superstructure. This name, battsagaan, became used for main assembly halls of other monasteries built in the same form.

The basic type of Maidar, Maitreya (Mong. maidar(i), Tib. byams-pa) temple was also very characterically Mongolian. They were usually two-story simple white temples, with their first floor built in Tibetan style with big trapezoidal windows. These housed a huge statue of Maitreya with a yurt-shaped and green roofed dome built at the top of the structure at the height of the statue’s head, thus surrounding the head of Maitreya. In Ikh khüree the big Maitreya temple was built in this style, but many other Maitreya temples in the countryside were also built like this. In modern Ulaanbaatar, Züün Khüree Dashchoilin (Mong. ǰegün küriyen / küriye dašičoyiling, Tib. bkra-shis chos-gling) monastery just built a modern version of this traditional Mongolian Maitreya temple form to house its newly installed Maitreya statue, thus rebuilding the Maitreya temple of the old Züün khüree monastic district.

Apart from all these, Mongolian monastery architecture had developed many other characteristic architectural solutions, for example for monasteries built in the Gobi area where almost everything was made of brick and mud.

In general, temples were built of bricks and mud, wood or stone as determined by local conditions. In most cases, different building materials were used within one complex. For example, the main temple building or some temple buildings were made of brick, other temples of wood, while the other buildings, dwellings of lamas, kitchens and other administrative buildings of brick and mud. Two types of bricks were widely used: ulaan toosgo, red-colored brick (Mong. ulaγan toγosqa), which was sun-dried brick, and khökh toosgo, blue or grey brick (Mong. köke toγosqa), which was fired brick. Bricks with different motives were used for decorative purposes, such as bricks with the soyombo symbol (Mong. soyombo, Tib. rang-byung, Skt. svayambhū; self-arising, being the first symbol of the soyombo alphabet invented by Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar) or with the vajra symbol (Mong. očir, Tib. rdo-rje, Skt. vajra).

Wood was used also in buildings of other materials for supporting structures and roofing, such as columns, pillars, and beams, and for windows and doors and their frames. Mainly pine wood was used from the northern taiga area. Stone was transported for building temples even from long distances and was used also for making the foundations for wooden or brick temples, for foundations of columns, or for making stone floors. Even now, at the site of totally ruined monasteries where stone had been used for foundations, these still mark the layout of the temples and buildings of the old monasteries.