Sectarian Discord within Islam during the Early Abbasid Period

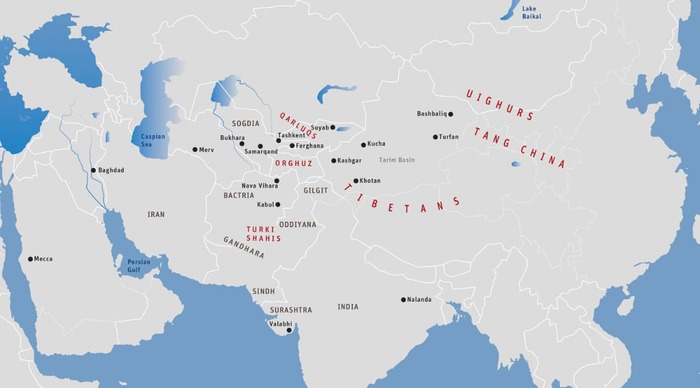

The Abbasids had succeeded in evicting the Tang Chinese forces from West Turkistan and the An Lushan rebellion in Han China had seriously weakened the Tang grip on Kashgar, Kucha, Turfan, and Beshbaliq. Nevertheless, it was not the Arabs, but the Qarluqs and Tibetans who took advantage of the power vacuum. The Qarluqs moved south, taking Suyab, Ferghana, and eventually Kashgar, while the Tibetans restrengthened their hold over the southern Tarim Basin city-states, especially Khotan, which they retook in 790. The Tibetans cut off all contact between the Khotanese royalty and the Tang court. The Tang, however, maintained a small outpost in Kucha and fought a protracted three-way war with the Tibetans and Uighurs over Turfan and Beshbaliq.

The Abbasids were never able to expand into any of the formerly Tang-held areas in West Turkistan because they became almost immediately embroiled in Islamic sectarian fighting in Sogdia. As soon as the second caliph, al-Mansur (r. 754 – 775), ascended the throne, he had Abu Muslim, the Shiite Bactrian who had helped the Abbasids establish their dynasty, put to death. Although his predecessor, Abu l’Abbas, had shown promise of nonpartisan treatment of all non-Arab subjects in his vast realm, al-Mansur reinstated the Umayyad preference for ethnic Arabs and the Sunni line of Islam. Subsequently, Sogdian opponents to Abbasid rule made Abu Muslim posthumously the defender of their Iranian culture against Arab domination. Using his martyrdom to rally their rebellions around avenging his death, they eventually regarded Abu Muslim as even a prophet.

Abu Muslim had originally used as his standard a black flag symbolizing the House of Ali. The Abbasids followed this precedent and used black for both their standard and dress. The Abu Muslim rebels, in protest, adopted the color white for their banners and clothing, which happened also to be the holy color of the Manichaeans and used for their robes. The Syriac epithet for Manichaeans was “Those with White Gowns.”

Manichaeism had many forms, blending with Zoroastrianism, Christianity, or Buddhism to resonate with people from different cultures. Its sophisticated ideas appealed to many intellectual officials in the Abbasid court, who developed an Islamic sect that combined Manichaeism with Shia Islam. The Abbasid authorities, as guardians of orthodoxy, eventually viewed the Manichaean Shiite sect as a threat. Branding it a heresy, they suspected its followers of anti-Abbasid sympathies akin to those of the Abu Muslim rebels in Sogdia and persecuted them. Although Manichaean Shia did not survive as a separate Islamic sect, many of its followers later absorbed themselves into the Ismaili sect of Shia. It, too, eventually became an object of severe persecution by the Abbasids.

During the reign of the next caliph, al-Mahdi (r. 775 – 785), most of Sogdia fell under the control of the white-robed rebels, led by al-Muqanna, the “Veiled Prophet,” an associate of Abu Muslim. The Oghuz Turks, who also wore white, gave military assistance to the rebels, although they never adopted Islam. By this time, the Sogdian rebels now followed a new Islamic sect, Musalemiyya, the customs of which did away with many orthodox traditions, such as praying five times a day. Thus, the Abbasid campaigns to quash the Sogdian rebels and their Oghuz Turk allies also became campaigns to preserve the purity of Islam.

In 780, the Abbasid forces put down a rebellion in Bukhara, but further uprisings continued. The Abbasids became preoccupied with suppressing these rebellions and with keeping the purity of Islam against the Musalemiyya and Manichaean Shia sects. Their urgency and harshness in dealing with heresies involving Manichaean elements was perhaps reinforced by former Zoroastrian priests who had converted to Islam and advised the government to follow the Sassanid example of authoritarianism in religious matters.

The Abbasid Destruction of Valabhi

In the early 780s, the Abbasid rulers in Sindh attacked Saurashtra and destroyed the large complex of Buddhist monasteries at Valabhi. After the fall of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty in 775, these religious institutions were without royal patronage and extremely vulnerable. This destruction, however, must be understood within the context of the uprisings in Sogdia and the persecution of the Musalemiyya and Manichaean Shia movements.

Valabhi was not only a center of Buddhist studies, it was also one of the holiest sites of the Shvetambara sect of Jainism. It had a very large number of Jain temples, not only Buddhist, and the Abbasid soldiers razed them as well. In fact, the Jain temples were in all likelihood their primary military targets. “Shvetambara” means “Those Dressed in White,” as monks of this tradition wear robes of this color. Undoubtedly misidentifying the members of this Jain sect as allies of the white-clad faction of Abu Muslim Musalemiyya rebels, their Orghuz Turk supporters, and the Manichaean Shiites, the Sindhi Arab leaders naturally would have perceived them as a threat and would have felt they must be eliminated. Once at Valabhi, they would not have differentiated the Jain temples from the Buddhist monasteries, and thus they destroyed everything.

As popular histories often cite the destruction of Valabhi as an example of Islamic intolerance of other faiths, let us examine the Abbasid religious policy as a whole in order to evaluate more objectively the historians’ judgment.

The Difference in Policy toward Manichaeism and Other Non-Muslim Religions

Despite their holy war against the Musalemiyyas and Manichaean Shiites, and in Saurashtra against the Jains and Buddhists whom they most probably confused as supporters of these sects, the early Abbasid caliphs continued the Umayyad policy of tolerance toward non-Muslim religions. They widely granted protected dhimmi status to their Buddhist, Zoroastrian, Nestorian Christian, and Jewish subjects. The only non-Muslims in their realm whom they persecuted were those who professed the Manichaean faith.

Unintentionally, the Arabs were continuing the anti-Manichaean policy of their predecessors in Sogdia, the Iranian Sassanids, and the Tang Chinese, but for different reasons. Firstly, the Manichaeans were undoubtedly identified in the Arabs’ minds with the Manichaean Shiites. Secondly, with its strong missionary movement and call to transcend the darkness and mire of this world, Manichaeism was challenging the appeal of orthodox Islam among the sophisticated Muslims in the Abbasid court. Any Muslim who leaned toward Manichaeism for spiritual matters was therefore accused of being a Manichaean Shiite, in other words an anti-Abbasid rebel.

The Strong Interest of the Abbasids in Indian Culture

Not only did the early Abbasids grant protected subject status to the non-Manichaean non-Muslims in their realm, they took great interest in foreign culture, particularly that of India. Although Arabs and Indians have had a great deal of economic and cultural contact since pre-Islamic days, with merchants and settlers from each group living in the area of the other, the Umayyad conquest and subsequent occupation of Sindh stimulated even greater exchange. In 762, for example, Caliph al-Mansur (r. 754 – 775) completed the construction of Baghdad, the new Abbasid capital. Not only did Indian architects and engineers design the city, they even gave it its name from the Sanskrit Bhaga-dada, meaning “Gift of God.”

In 771, a political mission from Sindh brought Indian texts on astronomy to Baghdad, marking the beginning of Arab interest in the subject. The Abbasid caliph realized the importance of more precise astronomical and geographic calculations for religious purposes, namely in order to determine accurately the direction of Mecca and the time of the new moon. He also appreciated that Indian civilization had the highest development of science in the region, not only in these subjects, but also in mathematics and medicine. The fact that these sciences had developed within a non-Muslim context did not at all preclude the Arabs’ openness to them.

The next caliph, al-Mahdi (r. 775 – 785), whose forces destroyed Valabhi, built a translation bureau (Arab. Baitu’l Hikmat) with scholars from all regional cultures and religions rendering texts, particularly on scientific topics, into Arabic. A large number of these works were of Indian origin, and not all their Sindhi translators were Muslims. Many were Hindus and Buddhists. The Abbasids were clearly pragmatic and interested in knowledge. Fundamentally, they were not opposed to Indian or other non-Manichaean foreign religions. Their caliphs seemed to take seriously the Hadith injunction of the Prophet to “seek knowledge, even if it be in China.”

This openminded, nonsectarian policy of seeking knowledge was not a passing fad, but continued with the next caliph, Harun al-Rashid (r. 786 – 809), who expanded it even further. His minister, Yahya ibn Barmak, for example, was a Muslim grandson of one of the Buddhist administrative heads (Skt. pramukha) of Nava Vihara Monastery. Under his influence, the Caliph invited to Baghdad many more scholars and masters from India, especially more Buddhists. There, the Buddhist scholars undoubtedly became aware of the trend toward Manichaean Shia among intellectuals of the Abbasid court and of the threat with which the authorities perceived them.

Having previously specialized in scientific texts, the translation bureau now began to produce works of a religious nature as well. For example, an Arabic version appeared at this time of the account of Buddha’s previous lives, Kitab al-Budd, based on two Sanskrit texts: Jatakamala and Ashvaghosha’s Buddhacharita. Parts of it were incorporated into the epic, Kitab Bilawhar wa Budhasaf, by Aban al-Lahiki (750 – 815), a poet of Baghdad. Although his version is no longer extant, many more were subsequently penned in many languages. The earliest surviving Arabic one is by Ibn Babuya of Qum (d. 991). This work passed from Islamic sources into Christian and Jewish literature as the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat, still retaining many Buddhist teachings. A further example of Abbasid openmindedness toward Buddhism is the Kitab al-Fihrist, a catalogue of both Muslim and non-Muslim texts, prepared at this time, which included a list of Buddhist works.

The Growth of Islam among Non-Muslims in West Turkistan

Harun al-Rashid was the greatest and most cultured of the Abbasid caliphs. Under him, Arabic poetry, literature, philosophy, science, medicine, and art all flourished. During his time, high Islamic culture had an evergrowing appeal to the non-Arab, non-Muslim aristocrats, landowners, and city-dwellers of West Turkistan, whose mentalities were totally different from that of the nomadic warriors of the steppes. Consequently, such persons gradually converted in ever-increasing numbers to the Muslim faith. The protected non-Muslim religions, such as Buddhism, remained strong mostly among the poorer peasant classes in the countryside, who followed them even more strictly than before as they started to become ethnic and religious minorities. They especially flocked to religious shrines for devotional practice.

Evaluation of the Destruction of Valabhi

The Abbasid destruction of the Buddhist monasteries at Valabhi, then, must be seen in the context of this larger picture. Islam was winning converts in Sogdia and Bactria at this time, not by the sword, but by the appeal of its high level of culture and learning. Buddhism was certainly not lacking in erudite scholarship and culture. However, in order to drink of it, one needed to enter a monastery. Nava Vihara, though still functioning during this period, was declining in prominence and was only one institution of learning. There were many Buddhists. The greatest Buddhist monastic universities of the day, such as Nalanda, were far off in the central part of northern India. Thus, the stronger and more readily accessible that Islamic high culture and study became in Central Asia, the more it eclipsed Buddhism among the upper, educated urban classes. This was, above all, a peaceful mechanism.

The destruction at Valabhi, then, was an exception to the general religious trends and official policies of the early Abbasid period. There are two plausible explanations for it. It was either the work of a militant fanatic general acting on his own, or a mistaken operation ordered because of the Arabs’ confusing the local “white-clad” Jains with supporters of Abu Muslim and then not differentiating the Buddhists from the Jains. It was not part of a jihad specifically against Buddhism.

The Arabic word jihad literally means “striving,” namely to serve Allah. It does not mean the type of holy war that is aimed at converting infidels by force to the only true faith. Rather, it is military action taken to defend fellow Muslims who are being attacked for practicing pure Islam or prevented in some way from their spiritual life. The Buddhists of Valabhi were not threatening Islam and were therefore mistaken objects for a justifiable jihad.

[See: Holy Wars in Buddhism and Islam: The Myth of Shambhala.]

The Abbasid Invasion of Gandhara

Although the Qarluqs and Abbasids had defeated Tang China at the Talas River in 751, the Qarluqs, having expanded into Suyab, Ferghana and Kashgar, soon broke their alliance with the Arabs and joined the Tibetans and their vassals, the Turki Shahis of Kabul. The White-Clad Oghuz, who had been supporting the Abu Muslim rebels, joined them as well in a concerted effort to gain control of Abbasid Sogdia and Bactria. The alliance therefore backed further Abu Muslim-styled rebellions against the Abbasids, such as the one led in Samarkand by Rafi bin-Layth from 806 to 808. Their combined forces even lay siege to Samarkand to aid the rebels.

Caliph al-Rashid died in 808 on his way to put down the rebellion. After his death, his empire was divided between his two sons in accordance with his wish. The two sons, however, made temporary peace with the Tibetans and their allies so that they could fight a civil war to gain total control of their father’s entire inheritance. Al-M'amun won and became the next caliph (r. 813 – 833). Undoubtedly blaming the Tibetan-Turki Shahi-Qarluq-Oghuz alliance for the death of his father, and associating the lot with the Abu Muslim Musalemiyya rebellions in Sogdia, he declared a holy war and sent General al-Fadl bin-Sahl to launch an all-out attack on the Turki Shahi state in Gandhara.

By 815, the Abbasids gained the victory and the Turki Shahi ruler, known as the Kabul Shah, was forced to present himself to the caliph at Merv and convert to pure Islam. As a token of his country’s submission, he sent a golden Buddha statue to Mecca, where it was kept for two years at the Kaaba treasury. It was displayed to the public with the notice that Allah had led the King of Tibet to Islam. The Arabs were confusing the King of Tibet with his vassal, the Turki Shah of Kabul. In 817, the Arabs melted down the Buddha statue at the Kaaba to mint gold coins.

After their success against the Turki Shahis, the Abbasids attacked the Tibetan-controlled region of Gilgit and within a short time annexed it as well. They sent a captured Tibetan commander in humiliation back to Baghdad. Although successful against the Tibetans and also in taking Ferghana from the Qarluqs, the Arab generals pressed their victories no further to the east or north. This was because the Abbasids were rapidly losing their grip on West Turkistan and eastern Iran as local military leaders were beginning to take over as governors of these regions and rule them as autonomous Islamic states.

The first region to declare its autonomy was Bactria, where General Tahir founded the Tahirid Dynasty (819 – 873). As the Abbasids withdrew from Kabul and Gilgit, turning their attention to these more pressing matters, the Tibetans and Turki Shahis regained their former holdings. Despite the forced conversions of the leaders of these lands, the Abbasids had not persecuted Buddhism there. In fact, the Arabs maintained trade with the Tibetans throughout this time, importing primarily musk. The Muslims and Buddhists even established cultural links with each other. Fazl Ullah, for example, translated into Tibetan at this time the Persian classics, Gulistan and Bostan.

Analysis of the Abbasid Campaign and Victory

Caliph al-Ma'mun had declared his campaign against the Tibetan-Turki Shahi-Qarluq-Oghuz alliance a jihad, a holy war. He was defending his Islamic subjects from heretical fanatics who were hampering their practice of the pure faith with campaigns of terror and rebellion. That was why, when he won, he not only insisted that the Kabul Shah convert to orthodox Islam, but also sent back the Buddha statue to be displayed at the Kaaba as evidence of the victory of Islam.

Reminiscent of what had undoubtedly inspired the Abbasid destruction of Valabhi, al-Ma'mun, however, probably misidentified his conquered enemies as members of the Musalemiyya and Manichaean Shia sects. His jihad against them would have been simply an extension of his father’s previous domestic campaigns. But, although the members of this foreign alliance supported the Abu Muslim rebels, they by no means followed their faith or Manichaean Shia. If they had, it would make no sense that throughout this period the Tibetans and Qarluqs were also fighting the Uighurs, the champion of the Sogdian Manichaean world.

The Tibetans were undoubtedly ignorant of the Islamic religious implications of the Sogdian rebellions. Furthermore, like the similar Tang Chinese effort sixty years earlier, the Tibetan attempt to destabilize Abbasid rule in Sogdia was not part of a program to win converts to Buddhism. It was purely a political and economic move to gain power, territory, and tax from the Silk Route trade. Tibetan religious leaders at the time were preoccupied with stabilizing Buddhism within their own borders and keeping it free from both internal corruption and secular control. Although these leaders participated in government, their sphere of influence did not extend to military matters. Their concern in external affairs was focused purely on cultural relations with Pala India and Tang China vis-a-vis the future of Buddhism in Tibet.

The Abbasids, in turn, were undoubtedly ignorant of the Turki Shahi and Tibetans’ religious beliefs. What they saw was simply foreign forces supporting a cult of religious fanatic rebels who were not only interfering in their subjects’ practice of Islam, but perhaps more importantly, trying to oust them from political power. The jihad was, in fact, directed at the Turki Shahi and Tibetans’ politics, not their Buddhist religion.

Al-Ma'mun was by no means a closedminded, religious fanatic. Like his father, Harun al-Rashid, he was culturally broadminded and continued to patronize the translation of Indian texts. His reign not only saw new heights in the scientific age of the Abbasids, but also an everincreasing dissemination of positive information about Indian civilization among the Arabs and their Muslim subjects. In 815, for example, the same year as the Caliph’s defeat of the Kabul Shah, al-Jahiz (b. 776) published in Baghdad Fakir as-Sudan ala l’Bidan (The Superiority of the Black over the White), which contained praise of the great cultural achievements of India. There were positive feelings about India, then, among the Abbasids at this time, and this would undoubtedly have extended to Indians of all religions, including Buddhism.

If al-Ma'mun’s jihad were against Buddhism itself, he should have aimed it not merely at the Tibetan-Turki Shahi-Qarluq-Oghuz alliance, but at the Indian subcontinent where Buddhism was much more in evidence and better established. However, after victory in Kabul, the Caliph’s forces attacked Gilgit and Ferghana, not Oddiyana. They had other objectives in mind.

Let us examine the situation in Tibet just prior to al-Ma'mun’s victories in Gandhara and Gilgit to appreciate the situation more fully. This may also help us to understand why the submission of the Kabul Shah and Tibetan military commander had hardly any effect on spreading Islam to Tibet or to its vassal states.