The remainder of the Umayyad period over the ensuing years of the first half of the eighth century saw a bewildering frequent change of alliances as even more powers entered the fray for control of West Turkistan and the Silk Route. Through a review of the main events, it will become obvious that the Umayyad Arabs were not fanatic religious extremists campaigning to spread Islam to a sea of infidels, but merely one of many ambitious peoples fighting for political and economic gain. All the powers, including the Umayyads, made and broke alliances continually, not based on religion, but on pragmatic, military grounds.

The Shifting of Alliances and Control of Territories

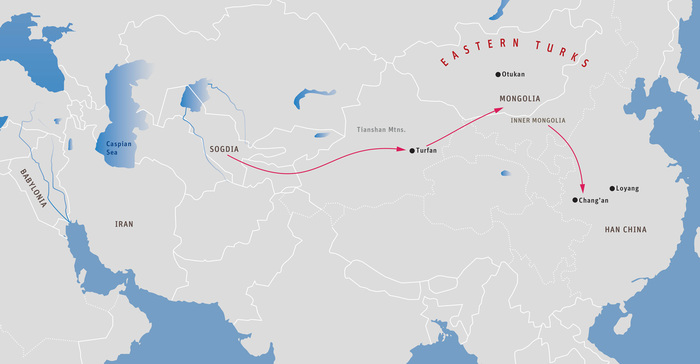

By the middle of Umar II’s reign (r. 717 – 720), the Umayyads controlled Bactria and the cities of Bukhara, Samarkand, and Ferghana in Sogdia. The Tibetans were their allies. The Turgish Turks held the rest of Sogdia, particularly Tashkent, as well as Kashgar and Kucha in the western Tarim Basin. The Tang Chinese forces were in Turfan at the eastern end of the Tarim Basin and in Beshbaliq across the Tianshan Mountains to Turfan’s north. The Eastern Turks held the rest of West Turkistan north of Sogdia, including Suyab, while the Tibetans maintained a presence along the southern Tarim route. A Tang sympathizer, however, was on the throne of Khotan. The Turki Shahis were confined to Gandhara. Except for the Umayyad Arabs, all the other power brokers in Central Asia were supporters of Buddhism to varying degrees. This seems, however, to have had no influence on the events that followed.

Taking advantage of the death of the Umayyad General Qutaiba, the Tang forces were the first to move. Setting out from their stronghold in Turfan and crossing East Turkistan north of the Tianshan Mountains, they took Kucha and Kashgar from the Turgish, attacking from the rear. Crossing the far western flank of the Tianshan into West Turkistan, they then captured Suyab from the Eastern Turks, Ferghana from the Umayyads, and Tashkent also from the Turgish.

At this point, the Turgish reorganized themselves under a different leader and a new group of Turks emerged on the scene, the Qarluqs (Kharlukh, Tib. Gar-log) in Dzungaria, who were also patrons of Buddhism. The Qarluqs replaced the Eastern Turks in the territory of northern West Turkistan beyond Tang-held Suyab and allied themselves with the Han Chinese. The Turgish, in turn, joined the Arab-Tibetan alliance. The Turgish then recaptured their homeland of Suyab and the Umayyads, in turn, took back Ferghana. Tashkent became temporarily independent. The Tang forces were left holding only Kashgar and Kulcha.

The Reassertion of Umayyad Rule in Sindh

In 724, the new Umayyad caliph, Hashim (r. 724 – 743), sent General Junaid south to reassert control over Sindh. The Arab-led forces succeeded in Sindh, but failed in their attempt to take Gujarat and West Punjab. As Governor of Sindh, General Junaid continued the previous Umayyad policy of exacting both a poll tax on the Hindus and Buddhists as well as a tax on pilgrims to the holy sites of both these religions.

Although the Hindu Pratihara rulers in West Punjab had the strength to drive the Umayyad forces from Sindh, they refrained from such action. The Muslims had threatened to destroy the major Hindu shrines and images if the Pratiharas attacked, and the latter considered the preservation of their holy places more important than regaining control over traditional territory. This is further indication that the Umayyad Arabs regarded the destruction of non-Muslim religious sites as primarily acts of power politics.

Umayyad Loss and Regaining of Sogdia

Meanwhile, with their confidence boosted by the return of their homeland in Suyab, the Turgish ended their short-term alliance with the Umayyads. Taking advantage of the deployment in Sindh of the major part of the Arab forces, the Turgish turned on the Umayyads, expelling them from Ferghana and nearby areas in Sogdia. The Tibetans followed the Turgish lead and also switched sides. The new Turgish-Tibetan alliance then turned on the Umayyads and, by 729, drove them from most of the rest of Sogdia and Bactria. The Arabs were left holding only Samarkand.

The Umayyads then allied themselves temporarily with Tang China to counter the powerful Turgish-Tibetan alliance. They defeated the Turgish at Suyab in 736. With the death of their king two years later, the Turgish tribes broke up and became very weak. The Han Chinese kept Suyab and continued their wars against the Tibetans, while the Umayyads moved back into Bactria and the rest of Sogdia. This prompted the Tibetans to reactivate their traditional alliance with the Turki Shahis by a visit of the Tibetan emperor to Kabul in 739 to celebrate a marriage alliance between Kabul and Khotan.

The Tang court now began a policy of supporting dissidents in the Umayyad-held cities of Sogdia. At one point, they even swept down from Suyab and pillaged Tashkent, which previously they had briefly held. Sino-Arab relations became strained. The conflict, however, was not based on religious grounds, but was purely politically motivated. Let us examine it more closely.

Analysis of the Tang Attacks on Umayyad-Held Sogdia

By exploring some of the policies of Xuanzong, the Tang Chinese emperor at this time, we can understand even more clearly that the late Umayyads were not aggressively seeking converts to Islam and that the Tang Emperor’s support of anti-Umayyad dissidents in Sogdia was not due to a Buddhist antipathy toward Islam.

Two events set the stage for the Emperor’s policies. Firstly, when Xuanzong’s grandmother, Empress Wu, had overthrown the Tang Dynasty by appealing to Buddhist millenarianism, she had exempted all Buddhist monks from taxes in order to win their support. Secondly, soon after the Emperor had ascended the throne, many Sogdians who had settled in Mongolia flocked to Han China. The Emperor’s responses to these two developments eventually led to his actions in Sogdia.

The Invitation of Sogdians to Mongolia and Their Subsequent Eviction

Although there had been Sogdian merchants along the Silk Route and in Han China for centuries before, a large influx of Sogdian immigrants came to the area in the mid-sixth century. Their influx was due to the religious suppressions of the Iranian Sassanid emperor, Khosrau I (r. 531 - 578). During the First Eastern Turk Empire (553 – 630), these Sogdians held a favored position with the Eastern Turks. Many were invited to Mongolia from their community in Turfan and were instrumental in translating Buddhist texts into the Old Turk language. The government used the Sogdian language and script for its financial business. During the course of the Second Eastern Turk Period (682 – 744), however, the powerful minister, Tonyuquq, steered its rulers on an anti-Buddhist course.

Tonyuquq blamed the Tang defeat of the First Eastern Turk Dynasty on the negative influence of Buddhism on the Turks. Buddhism taught gentleness and nonviolence, which robbed the Turks of their martial spirit. He called for a return to the traditional pan-Turkic cult of the nomadic warrior, wishing to use its strong ethos to unite all Turkic tribes behind him and fight the Han Chinese.

The Eastern Turks were the holders of Otuken (Turk. Ötukän), the Mongolian mountain sacred to all Turks according to their pre-Buddhist Tengrian and shamanist religions. Tonyuquq argued that the rulers he served were therefore morally obliged to uphold Turkic culture and values. Associating the Sogdians with Buddhism and the Han Chinese, he influenced Qapaghan Qaghan (r. 692 – 716) to drop the use of Sogdian and, for administrative purposes, employ instead the Old Turk language written in a Runic-style script. As the Sogdian population of Mongolia became increasingly unwelcome, they emigrated en masse to northern China in 713, settling particularly in Chang’an (Ch’ang-an) and Loyang (Lo-yang), the terminus cities of the Silk Route.

The Manichaean Factor

The Sogdian community in Mongolia had not been exclusively Buddhist. The majority, in fact, followed Manichaeism. This Iranian religion, founded in Babylon by Mani (217 – 276 CE), was an eclectic faith that adopted many features of the local beliefs that it encountered as it spread. It had two major forms – a western one in Asia Minor that accorded with Zoroastrianism and Christianity, and a later eastern one along the Silk Route that adopted strong Buddhist elements. Syriac and then Parthian were the official languages of the former, while Sogdian played a similar role for the latter.

Manichaeism had a strong missionary movement and the Sogdian followers of its eastern form, once in Han China, claimed it to be a form of Buddhism in order to win converts. They introduced it in this fashion to Empress Wu at the Chinese imperial court in 694 and, after their emigration from Mongolia, reintroduced it to the court in 719. This was after the Buddhist millenarian usurpation by the Empress had been overthrown and Tang rule restabilized. In 736, however, Emperor Xuanzong passed a decree forbidding Han Chinese from following Manichaeism and restricting the religion to non-Han subjects and foreigners. The reason given was that Manichaeism was a shallow imitation of Buddhism and was being spread as an imposter faith on the basis of a lie.

The Tang Emperor, however, was not sympathetic to Buddhism, and this criticism was not because of his wish to uphold the pure Buddhist teachings by cleansing it of heresy. There were many Han Chinese who were dissatisfied with the Emperor’s ambitious Central Asian campaigns because of the consequently high demand on them for taxes and military service. Xuanzong would have undoubtedly wished to avoid having a foreign, quasi-Buddhist religion available for Han Chinese that could act as a rallying point for focusing their dissent and possible rebellion.

The Emperor’s grandmother had deposed the Tang line by appealing to the cult of Maitreya Buddha. Since in Sogdian texts, Mani was frequently identified with Maitreya, and his grandmother had been favorably disposed toward Manichaeism, fears of a similar millenarian rebellion directed at him undoubtedly prompted the Emperor’s move against the Iranian religion.

Of the three religions of the Sogdian merchants in Han China – Manichaeism, Nestorian Christianity, and Buddhism – the first was by far the most aggressively oriented toward gaining converts. Several decades earlier, Arab and Iranian Muslim merchants had also started traveling to Han China. They came primarily by sea, not overland via the Silk Route, and settled in the coastal cities of southeastern China. A Muslim teacher, Sa’ad bin Ali wa Qas (d. 681), had even come with them. Yet, Xuanzong never issued a similar edict banning Han Chinese from following Islam. In fact, no subsequent Chinese emperor, Buddhist or otherwise, ever did either. They always followed a policy of religious tolerance toward Islam. This indicates that even if the first Muslims in Han China were involved in trying to spread their religion, this was not a major effort and never seen as a threat.

The Expulsion of Non-Han Buddhist Monastics from Tang China

As the years passed, the Tang Government became increasingly in need of funds to finance the Emperor’s ever more extensive campaigns in Central Asia. The tax-exempt status of the Buddhist monasteries from the time of Empress Wu’s usurpation seriously limited government income. Therefore, in 740, Xuanzong turned his support even more strongly toward Daoism, reimposed taxes on the Buddhist monasteries, and severely restricted the number of Han Chinese monks and nuns in his realm. He also expelled all non-Han Buddhist monastics as an unnecessary financial drain on the public.

Xuanzong’s support of anti-Umayyad dissidents in Sogdia, then, was clearly politically and economically motivated and had nothing to do with Islamic-Buddhist relations. The Emperor was not even a Buddhist and his deportation of Sogdian monks from Han China was certainly not a move to send them back to Sogdia to strengthen an anti-Islamic movement among Sogdian Buddhists. He expelled monks of other non-Han nationalities as well, not only Sogdians. Tang China was solely interested in gaining more territory in Central Asia at the expense of the Umayyads and controlling more of the lucrative Silk Route trade.

Final Events of the Umayyad Period

The last major event of the Umayyad period significant for future relations between Islam and Buddhism in Central Asia occurred in 744. The Uighur (Uyghur) Turks lived originally in the mountains of northwestern Mongolia, with some of their tribes wandering as far as the Tocharian-ruled Turfan region to the south and the Lake Baikal area of Siberia to the northeast. They were traditional allies of the Han Chinese against the Eastern Turks who controlled the Mongolian areas sandwiched between them.

In 605, as the first Han Chinese moved into the Tarim Basin in more than four centuries, the Sui Chinese emperor, Wendi (Wen-ti), had helped the Uighurs conquer Turfan, the center of Old Turk Buddhism. The Uighurs quickly adopted the Buddhist faith, especially in light of Wendi having declaring himself a Buddhist universal emperor. In 629, one of the first Uighur princes took the Buddhist name “Bodhisattva,” a title also used by Eastern Turk religious rulers. In the 630s, Tang China took Turfan from the Uighurs, but the latter still helped the Han Chinese put an end to the First Eastern Turk Dynasty shortly thereafter.

A half century later, the Second Eastern Turk Dynasty conquered the Uighur homeland with its aggressively pan-Turkic military policy. However, in 716, shortly after the Sogdians had fled Mongolia, the Uighurs won their independence. Subsequently, they continued to help their Han Chinese allies harass the Eastern Turks. Now, in 744, with the help of the Qarluqs in Dzungaria and northern West Turkistan, the Uighurs attacked and defeated the Eastern Turks and established their own Orkhon Empire in Mongolia.

The Oghuz tribe of Eastern Turks, known as the Turks of White Dress, migrated at this point from modern-day Inner Mongolia to the northeastern corner of Sogdia, near Ferghana. They soon played an important role in the complicated developments in Sogdia at the beginning of the Abbasid period. Furthermore, once in power, the Uighurs frequently fought with their vassals, the Qarluqs. The Uighurs and Qarluqs now inherited the roles of rival leaders of the eastern and western branches of the Turkic tribes. The Uighurs were in the ascendency, however, since they controlled Otuken, the Turks’ sacred mountain in central Mongolia near the Orkhon capital, Ordubaliq. The rivalry of these two Turkic people also set the stage for future developments.

Thus, the Umayyad era ended in 750 with the Arabs having lost and regained Bactria and Sogdia yet again. Their hold on the region was still precarious and their relations with the Buddhists, both among their subjects and their ever-changing allies and enemies, was still mostly based on political, military, and economic expediencies as before.