Buddhism as practiced by the Mongols is a local variation of Tibetan Buddhism, having its own spiritual head and some differences in its rituals and ceremonies, monastic robes and, in relation to its monasteries, some differences in their arrangement, architecture, and decorative arts. Mongolian Buddhism evolved with its own special features in accord with local conditions and customs. This ability to integrate the teachings with local practices and local deities and to adopt them to a different culture has always been a characteristic of Buddhism as it has spread to different countries in Asia. Let us survey some of these special features.

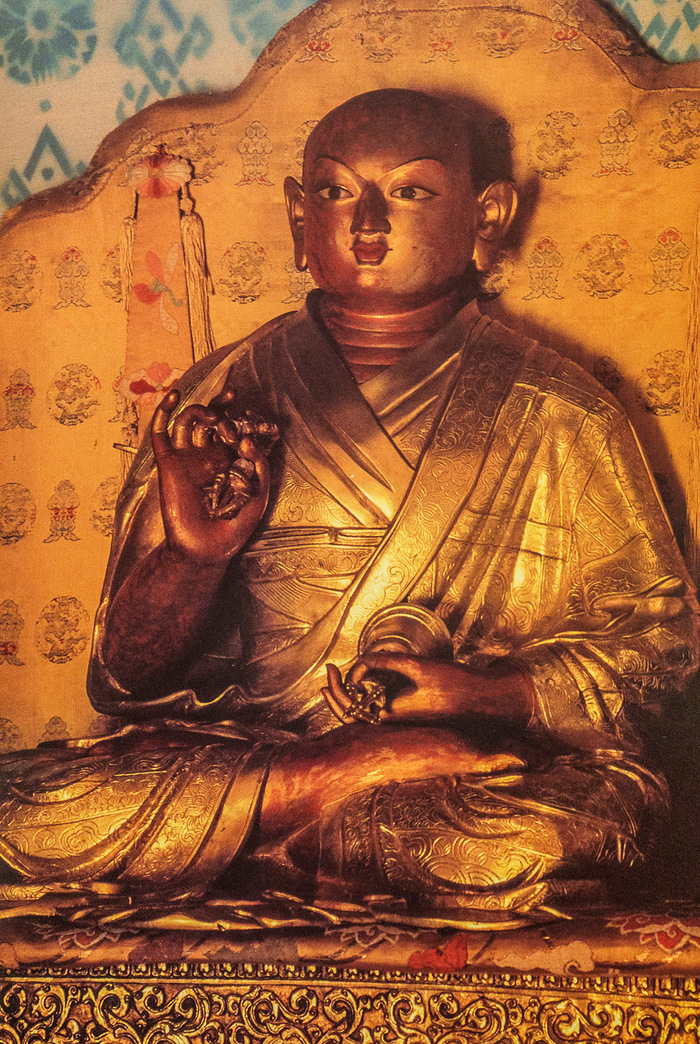

The Role of Zanabazar

Some of the distinctive features of Mongolian Buddhism, like those of architecture, and the arrangement and operation of monasteries, derive from the local circumstances and way of life. However, many other features are attributed to one specific historical person, Öndör Gegeen Zanabazar (1635–1723), the first Jebtsundampa Khutugtu or Bogdo Gegen (Bogdo Gegegen) of the Mongolians. By adapting Tibetan Buddhism to indigenous Mongolian customs and conditions and systematically incorporating local deities and rituals into it, he created a uniquely Mongolian Buddhism with special features in all aspects of ritual life.

Concerning his name and titles:

- Öndör Gegeen (Mong. öndür gegen < gegegen; The High Brilliant One) was his personal title.

- Zanabazar (Mong. ǰanabaǰar, Tib. ye-shes rdo-rje, Skt. jñānavajra; Deep Awareness Vajra) was his personal name.

- Jebtsundamba Khutugtu (Khal. jewzündamba khutagt, Mong. ǰibǰundamba qutuγtu), or simply Jebtsundampa, is the lineage title of the spiritual head of Mongolian Buddhism, of which Zanabazar was the first. The full title is a combination of the Tibetan title “Jebtsundampa” (rje-btsun dam-pa; literally, Hallowed, Ennobling, Impeccable One) and the Mongolian title “Khutugtu” (Khal. khutagt, Mong. qutuγtu, transliterated in Tibetan as ho-thog-tu, Tib. ’phags pa, Skt. ārya; Highly Realized One, Noble One). In short, “Jebtsundampa Khutugtu” could be translated as “Hallowed Noble One.”

- Bogdo Gegen or Bogdo Gegegen (Khal. bogd gegeen, Mong. boγda gegen < gegegen) is an alternative title for the Jebtsundampa Khutugtus. “Bogdo” (Khal. bogd, Mong. boγda, Tib. rje, Skt. svāmin) means “Master” and so “Bogdo Gegen” means “The Masterly Brilliant One.” The Bogdo Gegen is often referred to simply as the “Bogdo” or the “Bogdo Lama.”

Fifty years of communist suppression and the conditions at the time of the post-communist revival of Buddhism have affected the present state of the Mongolian traditions. Nevertheless, at the time of the revival a great emphasis was placed on preserving the special features of traditional Mongolian Buddhism and, subsequently, on maintaining them during the more than thirty years that have passed since then. The distinctive features introduced by Zanabazar form part of the national “Mongolian Buddhist identity” even today.

The Presence of Different Tibetan Buddhist Schools

Throughout history, different Tibetan Buddhist schools have been present in Mongolia, starting with the Sakya and Karma Kagyu schools in the 13th century. The Nyingma school was also present, but with Zanabazar in the 17th century the Gelug school became prominent and remains so until today. Only about one third of the temples in Ulaanbaatar (and even less in the countryside) currently belong to the Nyingma school. The same is true for the very few nunneries and laywomen’s centers, which are new establishments and not historical ones. There is only one Kagyu temple, but even this is not functioning daily, while the Sakya and Jonang traditions were lately reintroduced from India.

Religious Dignitaries and Organization

The Jebtsundampa Khutugtu, or Bogdo Gegen, is the third highest incarnation in the Tibeto-Mongolian hierarchy after the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas and was the highest Buddhist dignitary in Mongolia up to 1924. Although the first two Jebtsundampa Khutugtus were born in Mongolia, from the third incarnation onwards they were all born among the Tibetans in accord with the 1758 decree of the Qing emperor, Qianlong (1711–1799).

- The Eighth Jebtsundampa Khutugtu (1869–1924) briefly held the position of secular ruler of Mongolia from 1911 to 1921, during which time he held the title of Bogd Khan (Mong. boγda qan), meaning the Masterly Khan, or Masterly King.

- The Ninth Jebtsundampa Khutugtu (1924–2012) was officially installed in 1991, though recognized earlier in India, where he lived in exile, and enthroned in Mongolia in 1999. Thus, he became the leader of Mongolian Buddhists until his death, before which he only briefly lived in Mongolia.

- A tenth incarnation has not yet been found.

However, the abbot of Gandantegchenlin Monastery (Mong. γangdangtegčenling, Tib. dga’-ldan thegs-chen gling) – Gandan Monastery or just Gandan for short – the main monastery in the capital city Ulaanbaatar, is nominally referred to as the “head abbot” of the whole of Mongolia.

Concerning the name of the capital city:

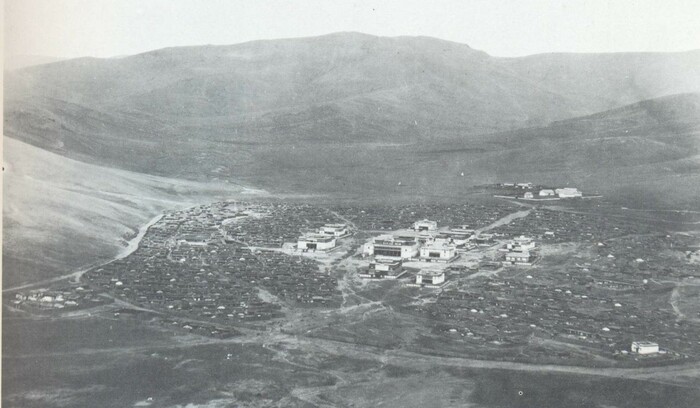

- Ulaanbaatar, meaning “Red Hero,” the present name of the capital of Mongolia, was the name given to the city at the time of the establishment of the Mongolian People’s Republic in 1924. Before that, between 1911 and 1924, it bore the name Niislel Khüree (Mong. neyislel küriyen / küriye), “Monastic Capital.”

- The original name of the city, founded in 1639, was Örgöö (Mong. örgüge) meaning “Palace,” and it became known in the West by this name in its Russian form, Urga.

- By 1706, the city became known as Ikh Khüree (Mong. yeke küriyen / küriye), the Great Monastic City, or Bogdyn Khüree (Mong. boγda-yin küriyen / küriye), the Monastic City of the Bogdo Gegen.

This duality of monastic leaders also existed historically. The Bogdo Gegen was the spiritual leader of the country and the Khamba Nomun Khan (Mong. qambu nom-un qan, Tib. mkhan-po chos-rgyal, meaning the Abbot King of the Dharma Teachings) was the head abbot (Khal. deed khamba, Mong. degedü qambu, the second word in the expression is Tib. mkhan-po, meaning abbot) of not only Ikh Khüree but of the entire country. Both resided in the monastic capital Ikh Khüree.

The Khamba Nomun Khan was the most important of the seven highest ranking lamas of the main assembly hall, the Ikh Tsogchin (Mong. yeke čoγčin, Tib. tshogs-chen) of Ikh Khüree. He was appointed by the Bogdo Gegen and, aside from Bogdo Gegen himself, he was regarded as the most significant cleric. The other six high-ranking lamas of the main assembly hall were the vice abbot (Khal. dood khamba, Mong. doγodu qambu) and the five Tsorj (Mong. čorǰi, Tib. chos-rje; Dharma master). This traditional pattern of the two leaders is still followed today, but as there is not an organized monastic system in the classical sense, the leadership of the Gandan abbot is partly nominal, though he is absolutely accepted and well respected countrywide.

Hundreds of Khutugtus and Khubilgans (Khal. khuwilgaan, Mong. qubilγan, Tib. sprul sku, Skt. nirmāṇakāya), incarnate lamas (tulkus), were also recognized and venerated in different areas and monasteries in pre-communist Mongolia. Among them were the thirteen main, privileged “Khutugtus with a Seal” (Khal. tamgatai khutagt, Mong. tamaγ-a-tai qutuγtu) – namely, the thirteen “Khutugtus” with a seal received from the Manchu emperors. They then served as administrative officials over the Buddhists in their areas (Khal. shaw’, Mong. šabi; literally disciple, alternatively also meaning subordinate area and subordinate people), running religious affairs independently from the Bogdo Gegen.

Apart from these privileged Khutugtus, there were many other Khutugtus recognized in Mongolia. The title does not connote that its holders are actually highly realized aryas, those who have nonconceptual cognition of voidness. Some scholars hypothesize that the Mongolian translation of the Tibetan “’Phags-pa” was chosen as the name of this title because of the veneration accorded to Chogyal Phagpa (Khal. choijal pagwa, Mong. čoyiǰal paγpa, Tib. Chos-rgyal ’Phags-pa) (1235–1280), known in Mongolia as Phagpa Lama (Khal. pagwa lam, Mong. paγpa lam-a / blam-a), the Imperial Tutor of Kublai Khan (Khal. Khubilai khan, Mong. qubilai qan).

Another important set of Khutugtus was known as the “Seven Main Khutugtus” (Khal. golyn doloon khutagt, Mong. γool-un doloγan qutuγtu), the “Seven Main Disciple Khutugtus of the Bogdo” (Khal. Bogdyn shawiin doloon khutagt, Mong. boγda-yin šabi-yin doloγan qutuγtu), or the “Seven Great Disciple Khutugtus” (Khal. ikh’ shawiin doloon khutagt, Mong. yeke šabi-yin doloγan qutuγtu). The term “ikh shaw’” (Mong. yeke šabi) in their alternative title, as we have seen above, can also mean “great subordinate areas” and is also applied to the people living in them. These seven areas were directly subordinate to the Bogdo Gegen, and these Khutugtus of the Seven Great Subordinate Areas administered the monasteries and the people in these seven areas.

The new incarnations of several of these Khutugtus, 22 in number as of 2022, related to certain old monasteries or lineages, have been recognized after the post-communist revival and most have been trained in the Tibetan monasteries re-established in India. Some are engaged in educating the new generation of lamas in Mongolia.

The term gegeen (Mong. gegen < gegegen) or gegeenten (Mong. gegenten < gegegenten), Brilliant One, is also used for incarnate lamas in Mongolian. We find it in the name of Öndör Gegeen and in the title Bogdo Gegen, but some other Khutugtus also had this title in their names.

In Mongolian, the word “lama” (Khal. lam, Mong. lam-a / blam-a, Tib. bla-ma) has a different meaning than it has in Tibetan. It refers to any member of the monastic assembly, irrespective of their level of attainment, their rank in the monastic hierarchy, the level of their pratimoksha vow or whether they are celibate or married. The term “emegtei lam” (Mong. emegtei lam-a / blam-a, female lama) is used for female members of the monastic community. In Mongolia, only lamas with full ordination vows keep celibacy. Novices usually do not, although there are a few exceptions.

Ritual Language, Recitation, and Melodies

Throughout history, Mongolians have created several writing systems. This means that today they use a different writing system from the classical one. The classical Mongolian or Uighur-Mongolian script (Khal. mongol bichig, Mong. mongγol bičig), which is vertical, was formed based on the Uighur script (deriving from Sogdian) which the Mongols adapted supposedly at the beginning of the 13th century. The Cyrillic script was introduced in Outer Mongolia in 1941 and is used today for modern Khalkha Mongolian. The classical Mongolian script is still used in Inner Mongolia, China. This classical or traditional Mongolian script basically mirrors the 13th century Mongolian language and does not follow the changes in the spoken language that have appeared since then. Therefore, it is basically a literary language above all dialects, and Mongolians who can read it pronounce it according to their own dialects.

After the democratic change at the start of the post-communist period, the Cyrillic writing was kept, but classical Mongolian writing is now taught again in schools, so educated people can read it and intellectuals use it. Those who attended school between the 1940’s and the 1990’s, however, can barely read it unless they learned it voluntarily as adults. In today’s Outer Mongolia the classical script is often regarded rather as a form of decorative writing. Young lamas now also receive public secular education, often in their own monasteries, where classical Mongolian writing is taught along with Tibetan writing.

Buddhist texts and treatises started to be translated into Mongolian as early as the 13th and 14th centuries. The Tibetan Buddhist canon, consisting of the volumes of the Kangyur (Khal. Ganjuur, Mong. ganǰuur, Tib. bka’-’gyur, the translated enlightening words of the Buddha) and later the volumes of the Tengyur (Khal. Danjuur, Mong. danǰuur, Tib. bstan-’gyur, the translated Indian treatises and commentaries to the Buddha’s teachings), were translated into Mongolian in the 17th and 18th centuries in different editions. All these were written in the classical Mongolian script.

Notwithstanding this, in spite of efforts and attempts from time to time in certain monasteries to conduct their rituals in Mongolian, the ceremonial language in Mongolian monasteries continues to be Tibetan, as it was throughout Buddhist history in the Mongol regions. The ceremonial books and manuals are all in Tibetan, the ceremonies are held in Tibetan, and training is conducted by the use and study of Tibetan ceremonial and philosophical texts. Religious terminology is mainly used in Mongolized Tibetan or is translated from Tibetan or, in a few cases, is of Sanskrit origin.

This situation has not changed with the post-communist revival even after fifty years of suppression. Because of this, devotees not only do not understand the ceremonies they attend, but also the language barrier makes it more difficult for them to improve their knowledge and understanding of the Buddhist teachings. However, in the past decades, basic Buddhist texts, ranging from prayers to complete philosophical treatises, have been translated into modern Mongolian and published in Cyrillic, enabling interested people to have a better understanding of the Buddhist teachings, which was not initially provided at the time of the revival. There is also a large project to translate the complete Tibetan Buddhist canon into modern Mongolian and publish it in Cyrillic. A great number of its texts have already been published. In addition, several institutions and centers are now providing longer and shorter courses in Buddhist studies and meditation for laypeople.

After the post-communist revival, several temples have attempted to conduct their prayers exclusively in Mongolian from texts written in the classical Mongolian. When texts are recited from classical Mongolian, however, they are pronounced in modern Mongolian but in a classicized form, and they include many elaborate expressions to express the terser classical language. They are also not always understandable due to the fast tempo of the recitation. This, however, resembles the situation among the Tibetans, where the classical Tibetan language of the Buddhist texts is even more different from spoken Tibetan, although the same writing system is used for both.

Two temples that experimented in conducting their prayers in Mongolian operated in Ulaanbaatar in the 2000’s, but both eventually closed down. In addition, after Gandan Monastery’s partial reopening in 1944, several texts were chanted in Mongolian, growing to more than ten since 1951. Its daily chant book still contains two of these in classical Mongolian script – the refuge prayer and Hundreds of Deities of Tushita (Khal. Gandanlkhawjaa(ma), Tib. dGa’-ldan lha-brgya-ma) the prayer of requests to the Gelug founder, Tsongkhapa. However, this practice of using the classical Mongolian script for these two prayers, which Gandan Monastery adopted because of a parliamentary decree at that time, did not become established in the long term and is currently not practiced.

More recently Züün Khüree Dashchoilin (Mong. ǰegün küriyen / küriye dašičoyiling, Tib. bkra-shis chos-gling), the second largest monastery in Ulaanbaatar, has started to recite two of its daily prayers – the same two as mentioned at Gandan – in Mongolian language, but from Cyrillic. They do this before starting their daily recitation of the rest of their prayers, which are all in Tibetan, including these two prayers in their original Tibetan versions as well. No other temples follow this precedent. All other Mongolian monasteries conduct their rituals exclusively in Tibetan, although sometimes, at certain events, a few chosen texts are recited in classical Mongolian or there are texts chanted in modern Mongolian from Cyrillic, with the aim of enabling laypeople to join in the recitation while understanding it. But otherwise, the ritual language is and seemingly remains Tibetan.

Nevertheless, despite the use of Tibetan language, Mongolian chanting has specialties that make it almost incomprehensible even for Tibetans. This is mainly due to the garbled, Mongolized pronunciation of Tibetan, but also due to the special styles of recitation and new melodies introduced by Zanabazar and later by the Fifth Jebtsundampa Khutugtu. The one introduced by Zanabazar is called the “old melody” (Khal. khuuchin yan, Mong. qaγučin yang) in contrast to the newer one by the Fifth Bogdo, the “new melody” (Khal. shine yan, Mong. šine yang). These differ from Tibetan recitation styles in their faster tempo. During the present Dalai Lama’s first visit to Mongolia after the revival, after participating in the first ritual of his visit at Gandan Monastery, he purportedly commented laughingly about the Mongolian way of chanting Tibetan, saying, “This was beautiful, but I did not understand even a word of it!”

The garbled pronunciation has also had an effect on the methods in which novices are taught Tibetan, as well as on the practice of monastic debate. As Mongolian language does not have all the phonemes or sounds of Tibetan, different Tibetan sounds are pronounced in the same way, resulting in many homonymous syllables. Therefore, when the Tibetan alphabet is taught or Tibetan words are spelled, the teachers sometimes need to use Mongolian words referring to the written form of the given letter (for example, “cha with two bellies”) or they need to add the Mongolian translation of a word beginning with the given letter (for example, “ja as in [the Tibetan word] tea”) to clarify which one of the Tibetan letters with the same Mongolian pronunciation is meant. Similarly, sometimes in monastic debate, Mongolian words or expressions are inserted for clarification to indicate which of the possible words with the same pronunciation is meant.

Ceremonial System and Ritual Texts

Among the Tibetans, individual monasteries differ in terms of the specific deities whose rituals the lamas perform, the specific rituals these entail and the specific lineages that these rituals come from. Daily chanting texts also differ from school to school and from monastery to monastery. In some cases, the rituals that are chosen depend on a special role the monastery plays, for instance the monastery of an oracle or medical or astrological colleges or temples. These differences in ritual practices apply to Mongolian monasteries as well. In Mongolia, however, during Zanabazar’s time, modifications were made to the general Tibetan ritual system regarding annual and monthly ceremonies and the prayers and texts chanted in the daily prayer sessions, and these were applied universally to all the monasteries in Mongolia.

For example, a main prayer of the Mongolian Buddhists, composed by Zanabazar and entitled “Bestowing the Highest Inspiration” (Khal. Jinlaw [or adistid, the Mongolized form of Skt. adhiṣṭhāna] tsogzol, Mong. ǰinglubčoγčol / ǰinglubčoγčal [or adistid for ǰinglub], Tib. Byin-rlabs mchog stsol), also called “A Prayer in Accordance with the Times” (Khal. Düitünji soldew, Tib. dus-bstun-gyi gsol-’debs), is recited daily in all Mongolian temples as are other Mongolia-specific texts, for example a eulogy of Öndör Gegeen and other eulogies and long-life prayers to the subsequent Bogdo Gegens. Prayers for the quick return of the next incarnation when one has passed away were also incorporated in the daily prayer sessions and other ceremonies.

Some ritual texts varied locally, such as eulogies of local Khutugtus and Khubilgans, incense offerings to the spirits of local mountains, golden drink libations, ceremonial cake offerings and other offering texts to local deities integrated into the Buddhist pantheon. These local variations are characteristic features of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries as well, but as already noted, Mongolians have a set of special texts recited daily in all Mongolian temples in addition to local variations. Mongolians also made their contribution to the Tibetan-language ritual literature, and some of their texts are also uniquely recited in Mongolian monasteries at other times, not in their daily rituals.

Many Tibetan ceremonies became modified in Mongolia with various new texts by Zanabazar and other Mongolian lamas added. Examples include the mantra recitation part added to the fifteen-day Great Prayer Festival (Khal. oroin yerööl or ikh yerööl, Mong. oroi-yin irügel < irüger or yeke irügel < irüger, Tib. smon-lam chen-mo) held starting at the Lunar New Year to commemorate Buddha’s defeat of six non-Buddhist challengers. All fifteen of the mantras that are recited then, and their unique melodies, were composed by Zanabazar. Another example is the playing of the cymbals 108 times in a melodious way, also introduced by Zanabazar, at the consecration (Khal. adislaga, Mong. adislaγa, Tib. byin-rlabs, Skt. adhiṣṭhāna) of the new annual ritual offering cakes that takes place on the 26th of the last winter month. Special Mongolian ceremonies were also introduced, such as one commemorating the death of Zanabazar on the 14th of the first spring month.

Further, unique types of tsam (Mong. čam, Tib. ’chams) ritual dance appeared in Mongolia with special characters, movements and melodies unique to Mongolia. Among them were the Jakhar tsam (Mong. ǰaqar, Tib. lcags-mkhar; Iron Palace Dance), named after the iron palace of the Lord of Death, Yama. This ritual dance is also called Khüree tsam, which could either be understood as the tsam where dancers move in a circle or as the tsam from the monastic city. This is because the word khüree (Mong. küriyen / küriye), meaning “circle” can also mean an “encircled place,” such as a monastic city, referring here to Ikh Khüree, the monastic capital from where this special tsam originated.

Monastic Robes of Lamas

The three main monastic robes (Khal. choigo, Mong. čoyiγ-a, or translated as Khal. nomyn khuwtsas, Mong. nom-un qubčasun, Tib. chos-gos, Skt. cīvara) worn by lamas in Mongolia originate from the Indian Buddhist tradition. These are:

- The lower garment (Khal. tangoi, Mong. tangγoi, Tib. mthang-gos, Skt. antarvāsa), a maroon skirt, commonly called a “shamthab” (Khal. shamtab, Mong. šamtab, Tib. sham-thabs, Skt. nivāsana) in Tibetan.

- The upper ceremonial garment (Khal. lagoi / lagai, Mong. laγai, Tib. bla-gos, Skt. uttarāsaṅga), a large yellow shawl, commonly called a “chögö” (Tib. chos-gos) in Tibetan, worn over the daily red shawl and only by fully ordained monks during the bimonthly confession ceremony, rituals such as the Maitreya procession or the 45-day summer retreat, and at teachings.

- The high ceremonial garment (Khal. namjir / namjar, Mong. namǰir / namǰar / namǰiyar, Tib. snam-sbyar, Skt. saṃghāṭī), an even larger yellow shawl, worn over the upper ceremonial garment and also only by fully ordained monks, but mostly only at ordinations and tantric initiations.

In addition, the Tibetan Buddhist monastic tradition has added:

- A maroon shawl (Khal. orkhimj, Mong. orkimǰi, Tib. gzan), worn daily by fully ordained and novice monks and nuns.

- A maroon or yellow vest (Khal. tongog / dongog, Mong. tongγoγ, Tib. stod-’gag) with protruding shoulders.

Note that for the pieces of robes taken from the Tibetan tradition, mostly the Tibetan name is used, as there is a Mongolian name only for the maroon shawl. All three types of shawls are worn across their body and the left shoulder, leaving the right shoulder free and uncovered.

Mongolian lamas use also a yellowish or brownish-colored sleeveless mantle with 108 folds, called janch (Mong. ǰangči / ǰangča). Any lama may own the yellow one, which is used against the cold, also in temples. In addition, the disciplinarian master (Khal. gesgüi, Mong. gesgüi, Tib. dge-bskos) in a monastery drapes it on his throne, lays it on the ground to make prostrations on it during certain rituals, and puts on it when reading out the names of donors for a given ritual. The brownish-colored one is only worn during tantric rituals and in Tantric and Kalachakra monastic schools.

It was thanks to Zanabazar that a reddish or yellowish-colored, modified form of the traditional Mongolian dressing gown, called deel (Mong. degel / debel), well-suited for the cold Mongolian climate, was added to the monastic dress. It is worn according to the weather conditions and there is no rule as to when to wear it. But when it is worn, it seems to replace the other basic pieces of monastic robes. It is worn over the lower garment or any simple pair of trousers or joggers, often with a Mongolian-style traditional shirt (Khal. tsamts, Mong. čamča) or a simple T-shirt replacing the vest. When the deel is worn, the maroon shawl is worn over it.

The lama’s deel differs in style from the traditional layperson’s deel in that it has no enger (Mong. engger) flap on the front side of the gown, but its edge runs straight from the left shoulder to the right armpit. In addition, the lining of the folded-back sleeves is blue. A more elegant variation of the lama’s deel, worn at great ceremonies by ranked lamas, is made of fine silk and has a wide black stripe on its front edge and possibly fur lining on the folded-back sleeves.

Arts and Decorative Arts

Other areas associated with ritual life also evolved with special features. For example, Zanabazar created two special writing systems, the more famous one being the soyombo (Mong. soyombo, Tib. rang-byung, Skt. svayambhū; self-arising) script, which has letters to represent the letters in the Tibetan and Sanskrit alphabets that do not occur in Mongolian. Though there remain different Buddhist texts written in this script, the soyombo script is used now, together with Tibetan, Sanskrit and Classical Mongolian scripts and sometimes also the Phagpa script, only for decorative writing found in monasteries in inscriptions, decorative paintings, and on prayer wheels. All these scripts, together with Cyrillic and perhaps Latin letters as well, can also be found on monastery name plates. The first letter of the soyombo alphabet – or rather the first symbol that is used to mark the beginning of a text – became the Mongolian national emblem and is depicted on the Mongolian national flag.

The other script Zanabazar developed is the horizontal square script (Khal. khewtee dörwöljin, Mong. kebtege dörbelǰin), or horizontal seal script, yet another of the many writing systems of the Mongols. It is called “horizontal” as opposed to the vertical square script (Khal. bosoo dörwöljin, Mong. bosuγ-a dörbelǰin) or Phagpa script (Khal. pagwa, Tib. ’phags-pa), which was created by the Tibetan Phagpa Lama in 1269 for Kublai Khan and used during the Yuan dynasty. Zanabazar’s horizontal square script also has letters for the Tibetan and Sanskrit letters not found in Mongolian, but it is hardly used at all.

Zanabazar was also an artist and sculptor. The special Mongolian style of Buddhist arts, called the “Öndör Gegeen school” or “Urga school,” derives from him. The artistic differences, however, are not so striking for a visitor to Mongolian temples since the basic rules of Tibetan Buddhist iconometry and iconography are kept.

Monasteries

Monasteries were also built, organized, and operated differently, having been adapted to the Mongolian conditions, traditions, and way of life. Not all monasteries were residential. In some cases, their lamas nomadized with their families and came to the monasteries only for ceremonies. There were also temples that were used only temporarily for occasional ceremonies, with only guard lamas that were resident for most of the year.

Some residential monasteries were built in a special design and were fenced off by a surrounding wall. In most cases, the lama residential districts (Khal. aimag, Mong. ayimaγ) were situated outside the walls and were built in a U-shape facing to the south. The buildings and yurts of the lamas that were grouped in these districts had their own aimag temples. The term “aimag” originally means “province” and was used for these monastic residential districts to indicate that all the lamas that lived in them came from the same province or smaller administrative division within them. These aimags were the old administrative divisions of Mongolia and are different from today’s provinces that are also called aimags.

Most of the monasteries, however, were not fenced off, but stood in an open area on the steppe, although some of the main temples might have been individually fenced off. The arrangement similarly followed the above U-shaped type, called khüree deg (Mong. küriyen / küriye dig), “arrangement in a circle,” with the residential aimag arranged around the center. Khüree is the Mongolian word for “circle” and deg is the Mongolized pronunciation of the Tibetan word “sgrig,” meaning an arrangement, or order. Later the term “khüree” became used in the meaning of monastery for large monastic cities, built mainly following this arrangement. There were also other types of arrangements, for example two typical ones for monasteries of the Gobi and other layouts for smaller monasteries. The Mongolians even have different words for “monastery,” depending on the size and the type of monastery it is.

Mongolian temple architecture also presents some special elements. It combined Tibetan and Chinese styles with characteristic Mongolian features and temple building types, for example yurt-shaped or octagonal wooden temples or the Maidar (Mong. maidar(i), Tib. byams pa, Skt. Maitreya) temples with a yurt-shaped dome on top of them. Smaller temple complexes operated in yurts, sometimes with small wooden or brick buildings for the kitchen or storage built next to them.

Monasteries were built with materials that were mostly available locally, although sometimes transported from distant places. The building materials included sun-dried or burnt bricks, mud, wood, and stone – either granite or slate. After the post-communist revival, there were very few surviving monastery buildings available to reopen. All other monastic assemblies were restarted in yurts or in newly built temples. Some of these temples that were opened after the revival have already closed because of the death of the old lamas who once headed them or due to a lack of financial resources, but new ones have also been opened from time to time.

Apart from a few larger monasteries in Ulaanbaatar and in other locations countrywide, monasteries today have only one or two temples and are nonresidential. Their being nonresidential is partly a cause or maybe rather a consequence of the lifestyle of present-day Mongolian lamas.

Purity of Monastic Discipline

Despite the differences in all areas of ritual life, it is still the Tibetan tradition of Buddhism and its various schools that are present and practiced in Mongolia. It is not possible for the vinaya rules of monastic discipline contained in the volumes of the Kangyur, the translated words of the Buddha, to be changed or compromised. Thus, differences in Mongolia from the Tibetan form of keeping the purity of the monastic vows, no matter what historical occurrences or social conditions account for them, cannot be considered as special features of Mongolian Buddhism but rather as a deviancy. Mongolian Buddhist monks do not keep celibacy, which is problematic from the point of view of adhering to the vinaya, especially as, at the same time, the monks still perform the sojin or sojong (Mong. soǰung, Tib. gso sbyong, Skt. poṣadha) confession ritual for purifying and restoring the vinaya vows twice a month, as in Tibet.

The extent of these deficiencies in purity is greater now than it was in the past. The roots of this increase lay in the recent history of Mongolia – in the way in which the post-communist revival was executed and in the modern social setting. While the Tibetan tradition, despite the persecutions and tragic events of the 1950’s, has managed to be preserved intact in exile, even though within restricted possibilities, Mongolian Buddhist traditions and lineages were completely broken for fifty years. The few surviving lamas were forced into secular life for decades, including getting married, and religion was restricted to rare secret meetings. When Gandan Monastery was reopened in 1944 as the only place of worship till 1990, its handful of lamas were carefully chosen by the authorities, not always based on their knowledge but determined by other factors. After 1970, the number of lamas grew gradually, but most of the new lamas that were accepted were young or middle-aged men already married and not the old surviving lamas.

Later, the mostly already married old former lamas who still knew the tradition enthusiastically took a main role in the revival of Mongolian Buddhism and this was indeed the only way the revival could be achieved keeping the traditional characteristic features. However, the revival was also helped by different Tibetan lamas and institutions, and in the last decades many Mongolian young lamas have studied in the Tibetan monasteries and monastic schools of India; yet, still there is no improvement in the question of adherence to the vinaya. Monasteries and temples remain nonresidential, with only a very few ones providing dormitories, with most lamas merely going to work there but otherwise living with their wives and children. Only the few lamas who have taken the full monastic vows of gelen (Mong. gelung, Tib. dge slong, Skt. bhikṣu) keep celibacy. As for now, this remains a considerable difference from Tibetan Buddhism.