Inciting and Incited Karmic Impulses

In A Discussion for the Establishment of Karma (Las-grub-pa’i rab-tu byed-pa, Skt. Karmasiddhiprakaraṇa) (Derge Tengyur vol. 136, 144B), Vasubandhu states:

Suppose you ask, “Well then, has the Bhagavan (Buddha, the Vanquishing Master Surpassing All) spoken of inciting karmic impulses and incited (karmic impulses)?” (Yes, he has.) Having been urged by the (first) two out of those mental urges that were previously explained as being of three kinds, the third one, since it had an initially engager, is a karmic impulse that an urging brings about.

(Tib.) /’o na ci ste bcom ldan ’das kyis sems pa dang / bsam pa’i las zhes gsungs she na/ sngar sems pa rnam pa gsum bshad pa gang yin pa de las gnyis kyis ni bsams la/ gsum pas ni rab tu ’jug par byed pas de ni bsams pa’i las zhes bya’o/

As Vasubandhu, A Discussion (Derge 144A), explains:

Mental urges are of three kinds: one that causes the coursing, (one that causes) the deciding and (one that causes) the moving.

(Tib.) /sems pa ni rnam pa gsum ste/ ’gro ba dang / nges pa dang / g.yo bar byed pa’o/

All three kinds of mental urges are directed at the body or speech. The mental urges that cause the coursing (’gro-ba) and the deciding (nges-pa) are for the karmic actions of the mind that course and scrutinize whether to commit a karmic action of the body or speech and decide to commit it. The mental urge that causes the moving (g.yo-ba) is for the karmic action of the body or speech in which the body or speech is moved to commit the action.

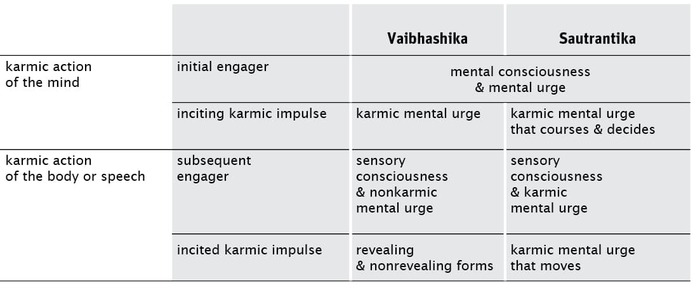

Sautrantika asserts that the first two kinds of mental urges are inciting karmic impulses and the third is an incited karmic impulse.

- An inciting karmic impulse (sems-pa’i las, Skt. cetanākarma) – literally, an “urging karmic impulse” – the mental factor of an urge that is the karmic impulse for a karmic action of the mind and that can lead to a further karmic impulse, one for a karmic action of body or speech.

- An incited karmic impulse (bsam-pa’i las, Skt. cetayitvākarma) – literally, a karmic impulse that an inciting karmic impulse brings about – the mental factor of an urge that is a karmic impulse for a karmic action of the body or speech and that is preceded by a karmic action of the mind with which an inciting karmic impulse is congruent.

Furthermore,

- The mental consciousness in the karmic action of the mind to scrutinize and decide to commit the karmic action of the body or speech is the initial engager (rab-tu ’jug-byed-pa, Skt. pravartika) of the body or speech.

- The sensory consciousness in the karmic action of body or speech in which one enacts what one has scrutinized and decided to do or say is the subsequent engager (rjes-su ’jug-byed, Skt. anuvartika) of the body or speech.

In A Discussion, Vasubandhu applies the two terms, “initial and subsequent engagers,” to the Sautrantika presentation of the three types of mental urges:

- The initial engager of the body or speech for committing a premeditated action of the body or speech is the mental consciousness that is affected by the first two types of mental urges – the mental urges that cause the coursing and the deciding.

- The subsequent engager of the body or speech is the sensory consciousness that is affected by the third type of mental urge – the mental urge that causes the moving.

In the Vaibhashika context:

- The mental urge that drives the initial engager mental consciousness is an inciting karmic impulse.

- The mental urge that drives the subsequent engager sensory consciousness is not the karmic impulse in the karmic action of the body or speech. The incited karmic impulses are the revealing form (rnam-par rig-byed-kyi gzugs, Skt. vijñaptirūpa) and the nonrevealing form (rnam-par rig-byed ma-yin-pa’i gzugs, Skt. avijñaptirūpa) of this karmic action of the body or speech.

The Sautrantika assertion is:

- The mental urge that drives the initial engager mental consciousness is an inciting karmic impulse.

- The mental urge that drives the subsequent engager sensory consciousness is the incited karmic impulse in the karmic action of the body or speech.

Analysis of the Debate Regarding Inciting and Incited Karmic Impulses

Unpacking the debate between Vaibhashika and Sautrantika concerning inciting and incited karmic impulses hinges on identifying the grammatical variants of the Sanskrit verbal root, cit, translated in this context as “to urge,” which can be reconstructed from the Tibetan translations.

- In a more general context, cit means “to cognize,” sometimes translated as “to think.” The Sanskrit general term for “mind,” citta, derives from this root and is translated into Tibetan as sems.

- The Sanskrit terms translated here as “inciting” (cetanā) and “incited” (cetayitvā) karmic impulses also derive from the root cit. Thus, they are translated into Tibetan respectively as sems-pa and bsam-pa, based on the more general meaning of cit, “to think.” Sems-pa connotes karmic impulses that think about committing a karmic action of the body or speech, while bsam-pa connotes karmic impulses for or in the karmic actions of body or speech that have been thought about.

The Tibetan terms, however, do not explicitly convey all the nuances of the Sanskrit grammatical forms. Therefore, to make the explanation of the above passage from Vasubandhu, A Discussion, easier to follow, we shall use the literal translation of the Sanskrit terms for inciting and incited karmic impulses – namely, an “urging karmic impulse” and a “karmic impulse that an urging brings about.”

In An Annotated Commentary on (Vasubandhu’s) “(Discussion for) the Establishment of Karma” (Las grub pa’i bshad pa, Skt. Karmasiddhiṭīkā) (Derge Tengyur vol. 138, 100A), Sumatishila explains:

As for “Well then,” this indicates another contradiction that others (Vaibhashika raises). As for “Well then, has the Bhagavan (Buddha, the Vanquishing Master Surpassing All),” the word “why?” needs to be filled in (so that the question becomes “Why has the Bhagavan…”).

This is (the contradiction): “In the case where (a karmic impulse that) an urging brings about is nothing other than another karmic impulse (that is a form of physical phenomenon), it is reasonable that it is called (a karmic impulse that) an urging brings about. That’s because it has been rendered into having the functional nature of a karmic impulse for (an action of) the body or speech by means of a mental urge. Yet (in the case where a karmic impulse that an urging brings about has) existence as something that is an urging, it is unreasonable that it is made to urge. Something that (already has) existence as that (as what it inherently is – namely, an urging) cannot be caused (to exist as what it already is).

This being (the objection), then with “mental urges previously (explained)” and so on, the masterful teacher (Vasubandhu) has answered. As for “mental urges that were previously explained as being of three kinds,” (they are of three kinds) since they have been divided into “mental urges that cause (the mind) to course” and so on. As for “(Having been urged) by the (first) two of those (mental urges),” it is by the two: the one that causes (the mind) to course and the one that decides. As for “the third one, since it had an initial engager,” it is the one that causes (the body) to move. As for “it,” it is the karmic impulse that causes (the body) to move.

(Tib.) /’o na zhes bya ba la sogs pas ni gzhan dag ’gal ba gzhan ston pa yin no/ /’o na ci ste bcom ldan ’das kyis zhes bya ba ni ’o na ci’i phyir zhes bya ba’i tha tshig ste/ bsam pa ni logs shig nas las gzhan zhig med pa ma yin pa de’i ltar na sems pas lus dang ngag gi las kyi rang bzhin du byas pa’i phyir bsams pa’i zhes bya bar rigs kyi/ gang gi ltar na sems pa nyid lus la sogs pa’i las yin pa de’i ltar na sems par byed par mi rigs te/ de nyid kyis de byed pa ma yin no zhes bya ba ’di yin no/ /sngar sems pa zhes bya ba la sogs pas ni slob dpon gyis lan btab pa yin no/ /sngar sems pa rnam pa gsum bshad pa zhes bya ba ni ’gro bar byed pa’i sems pa zhes bya ba la sogs pa’i dbye bas so/ /de las gnyis kyis ni zhes bya ba ni ’gro bar byed pa dang / nges pa gnyis kyis so/ /gsum pa ni rab tu ’jug par byed pas zhes bya ba ni g.yo bar byed pas so/ /de ni zhes bya ba ni g.yo bar byed pa’i sems pa’o/

The point of contention is how to interpret the causative element of cetayitvā, which is the causative gerund inflection of the Sanskrit root cit. In the context of both the Vaibhashika and the Sautrantika presentations of karma, the literal translation of cetayitvā is a “karmic impulse that is caused by an urging” or a “karmic impulse that an urging brings about.” Both presentations accept that the causal relationship between an urging karmic impulse and a karmic impulse that an urging brings about refers to the former being the cause for the latter to arise. The argument revolves around another issue. If the mental urge that drives the sensory consciousness in the karmic action of the body or speech is the karmic impulse that an urging brings about, as Sautrantika asserts, then how to interpret other connotations of the causal inflection of the term cetayitvā, a karmic impulse that an urging brings about, or that an urging causes?

Sautrantika argues that the causal relationship between the mental urge that is congruent with the mental consciousness in the initial karmic action of the mind and this mental urge in the subsequent karmic action of the body or speech is not that the former causes the latter to exist as something that urges. In this regard, it makes no difference whether the mental urge that drives the sensory consciousness in the karmic action of the body or speech is asserted as a karmic impulse by us or as a non-karmic impulse by you Vaibhashikas. Thus, Sautrantika accepts the Vaibhashika point that something (a mental urge) that has “existence as something that is an urging” (sems-pa-nyid, Skt. cetakatva) cannot “be made to urge” (sems-par byed-pa, Skt. cetayati), since it already has “existence as what it inherently is” (de-nyid, Skt. tattva), an urging.

The Sautrantika explanation of the causal relation between the two mental urges, however, is in terms of the three types of mental urges that engage the body or speech. The mental urges that cause the coursing and deciding in the karmic action of the mind are the urging karmic impulses and the mental urge that causes the moving in the karmic action of the body or speech is the karmic impulse that an urging brings about. The causal relation between the two mental urges is that of the initial engager and the subsequent engager of the body or speech.

Sumatishila echoes Sthiramati, who stated in The Meaning of the Facts, An Annotated Subcommentary to (Vasubandhu’s) “Autocommentary to ‘A Treasure House of Special Topics of Knowledge’” (Chos mngon-pa mdzod-kyi bshad-pa’i rgya-cher ’grel-pa don-gyi de-kho-na-nyid, Skt. Abhidharmakoṣa-bhāṣyā-ṭīkā-tattvārtha) (Derge Tengyur vol. 210, 11B):

Well, (says Vaibhashika), when (Sautrantika) expands (the range of) what are called “mental urges” and explain karmic impulses for (actions of) the body and speech as only mental urges, then being that like, there would be no such thing as a karmic impulse that an urging brings about. Since (that would be the case), then suppose (Vaibhashika) asks, “How is this not in contradiction with the sutra from which comes the line, ‘There are urging karmic impulses and (karmic impulses) that an urging brings about?’”

(Sautrantika) extensively replies, “It (an urging karmic impulse) is (a mental urge) that thinks, ‘because of that, I shall do like that.’” From having taken as its urging the scrutinizing mental urge that has thought, “I shall do like this and this,” then later another mental urge arises for enacting (that action), because it is the subsequent engager at the time of enacting it. That (mental urge) which engages the body (at that later time) is called “a karmic impulse that an urging brings about.”

(Tib.) ’o na gang sems pa zhes bya ba rgyas par ’byung ste/ ’dir lus dang ngag gi las ni sems pa kho na la bshad na/ de lta yin na bsam pa’i las gang yin pa de med pas/ sems pa dang bsam pa’i las so zhes ’byung ba’i mdo ’di dang ji ltar mi ’gal zhe na/ de’i phyir ’di lta bu zhig bya’o snyam zhes bya ba rgyas par smos so/ /dpyod pa’i sems pa ’di dang ’di lta bu zhig bya’o snyam du sems par bzung nas/ phyi nas gzhan bya ba’i sems pa ’byung ste/ bya ba’i tshe rjes su ’jug pa’i phyir ro/ /gang gis lus ’jug par byed pa de ni bsam pa’i las zhes bya ba’o/

Karmic Impulses for Actions of Speech

Vasubandhu, A Discussion (Derge 144B), then goes on to explain karmic impulses for actions of the speech:

The phrases of speech are individual instances of vocalizations, through which a meaning is made understandable. The karmic impulses (for them) are the mental urges that cause them (these vocalizations) to arise. They (the phrases) are also speech because they are (comprised of) units that are (vocalized) syllables or because they make one’s intended meaning into something that is verbalized. And as for “(speech) karma,” as before, it is a karmic impulse that gives rise to (motivates) speech, because, as before, the word “for” has not been made explicit.

(Tib.) /ngag gi tshig ste/ dbyangs kyi khyad par gang gis don go bar byed pa’o/ /las ni de slong bar byed pa’i sems pa’o/ /yi ge’i rnam pa yin pa’i phyir ram/ ’dod pa’i don rjod par byed pas na yang ngag go/ /las ni snga ma bzhin du ngag kun nas slong bar byed pa ni las te/ snga ma bzhin du bar gyi tshig mi mngon par byas pa’i phyir ro/

Sumatishila, An Annotated Commentary (Derge 100A–100B), elaborates:

Having extensively detailed karmic impulses for (actions of) the body and so on, now (Vasubandhu), wishing to explain specifically karmic impulses for (actions of) speech, says, “(The phrases of) speech,” and so on. As for “individual instances of vocalizations through which a meaning is made understandable,” they are (for example): “Alas, affected phenomena are nonstatic,” and so on. As for “that cause them to arise,” (it means) that cause speech to arise. As for “are (comprised of) units that are (vocalized) syllables” and so on, this indicates that speech is actualized as (being comprised of) units that are other things. As for “because they are (comprised of) units that are (vocalized) syllables,” (it means) since (speech has) the functional nature of being (comprised of units that are vocalized) syllables, therefore vocalizations in the manner of distinctly pronounced phrases are called “speech.” As for “since they make one’s intended meaning into something that is verbalized,” one’s intended meaning (signifies that) they (these vocalized phrases) verbalize to others the meaning that one intends to verbalize, since they make (those vocalized syllables) indicate (that meaning). In this (regard) as well, vocalizations in the manner of distinctly pronounced phrases are called “speech.”

As for “as before,” it needs to be filled in that just as how it was established that what affects the mind of an agent who exhibits a karmic impulse is that which is called “a karmic impulse,” so too it needs to be made evident here as well. As for “because, as before, the word ‘for’ has not been made explicit,” (it means) just as it was established in reference to a body karmic impulse (by the line), “because the word ‘for’ has not been made explicit, as in (the expressions) ‘medicinal treatment grain butter’ and ‘dust wind,’” so too it (the word ‘for’ in the phrase “karmic impulse ‘for’ the speech”) needs to be made evident in reference to a speech karmic impulse as well.

(Tib.) /de ltar lus la sogs pa’i las rgya cher rnam par phye nas/ da ni ngag gi las rnam par bshad par bzhed nas/ ngag ni zhes bya ba la sogs pa gsungs so/ /dbyangs kyi khyad par gang gis don go bar byed pa’o zhes bya ba ni/ kye ma ’du byed rnams mi rtag /ces bya ba la sogs pa’o/ /de slong bar byed pa zhes bya ba ni ngag slong bar byed pa’o/ /yi ge zhes bya ba la sogs pas ni ngag rnam pa gzhan du sgrub pa bstan to/ /yi ge’i rnam pa yin pa’i phyir zhes bya ba ni yi ge’i rang bzhin yin pa’i phyir na nges pa’i tshig gi tshul gyis dbyangs la ngag yod ces bya’o/ /’dod pa’i don rjod par byed pas na zhes bya ba ni ’dod pa’i don te brjod par ’dod pa’i don gzhan la rjod par byed/ rab tu ston par byed pas so/ /’dir yang nges pa’i tshig gi tshul nyid kyis dbyangs la ngag ces bya’o/ /snga ma bzhin du zhes bya ba ni ji ltar lus kyi las bstan par byed pa po’i yid mngon par ’du byed pa ni las so zhes las bsgrubs pa de nyid ’dir yang blta bar bya’o zhes bya ba’i tha tshig go/ /snga ma bzhin du bar gyi tshig mi mngon par byas pa’i phyir ro zhes bya ba ni ji ltar lus kyi las ni sman pa la’i ’bru mar lta bu dang rdul gyi rlung zhes bya ba bzhin te/ bar gyi tshig mi mngon par byas pa’i phyir ro zhes bsgrubs pa de bzhin du ngag gi las la yang blta bar bya’o/

Vaibhashika defines the karmic impulse for an action of speech as including both a revealing form and a nonrevealing form of speech. The revealing form of speech is taken as the type of sound with which one implements a method for causing the action of speech to occur. The method is to vocalize the sound of the voice. The sound of a voice is defined as the type of sound that has as its cause appropriated great elements and that is communicative of a limited being (a sentient being). It may be pleasing or unpleasing. “Appropriated” (zin-pa, Skt. upātta) means “taken as the physical support for a consciousness.” Thus, appropriated great elements (earth, water, fire and wind) are the great elements of a live body and not of a corpse or of an emanated body. A sound that is “communicative of a limited being” (sems-can-du ston-pa, Skt. sattvāvākhya) means a sound that, when heard, causes the hearer to know that it was made by a limited being.

Sautrantika defines the karmic impulse for an action of speech as the mental urge that affects a sensory consciousness to engage the speech to implement a method for causing the action of speech to occur. Sautrantika agrees with Vaibhashika that the implemented method for causing an action of the speech to occur is to speak. But rather than explaining the act of speaking in terms of the specific type of sound that it produces, Sautrantika explains the act of speaking as the vocalization (dbyangs, Skt. ghoṣa) of distinctly pronounced phrases (nges-pa’i tshig, Skt. niruktapada), through which a meaning is made understandable, and which are comprised of vocalized syllables (yi-ge, Skt. vyañjana) that communicate that desired meaning to others.

Karmic Impulses for Actions of the Mind

Vasubandhu, A Discussion (Derge 144B), continues with the explanation of karmic impulses for actions of the mind, specifically those actions of the mind that do not scrutinize and decide to commit an action of the body or speech:

(Mental) consciousness is mind because it is that which takes (the aggregates) as being “mine.” Or it is mind because it is that which causes further rebirths and encounters with objects (during those rebirths). The rest is like the words that were indicated previously.

(Tib.) /rnam par shes pa ni yid de/ nga yir byas pa’i phyir ram/ skye ba gzhan dang / yul la gzhol bar byed pa’i phyir yid do/ /lhag ma ni sngar ji skad bstan pa bzhin no/

Sumatishila, An Annotated Commentary (Derge 100B), explains:

Having established in detail (what) karmic impulses for (actions of) speech are, now for establishing (what) karmic impulses for (actions of) the mind are, (Vasubandhu) says, “(Mental) consciousness,” and so on. As for “(Or mental) consciousness is mind,” the meaning, “(Mental) consciousness is to be known as ‘mind’ (in the phrase ‘karmic impulses for actions of the mind’).” Suppose you ask how it is that (mental) consciousness is mind. (Vasubandhu) says, “because it is that which takes (the aggregates) as being ‘mine’” and so on. “Because it takes (the aggregates) as being ‘mine’ – namely, as being ‘me and mine’” means “because it takes (the aggregates) as being one’s own.”

(Tib.) /ngag gi las bye brag tu bsgrubs nas/ da ni yid kyi las bsgrub pa rnam par shes pa ni zhes bya ba la sogs pa gsungs so/ /rnam par shes pa ni yid de zhes bya ba ni rnam par shes pa la yid du rig par bya’o zhes bya ba’i tha tshig go/ /ji ltar na rnam par shes pa la yid ces bya zhe na/ de’i phyir nga yir byas pa’i phyir zhes bya ba la sogs pa gsungs te/ nga dang nga’i zhes nga yir byas pa’i phyir te/ rang gir bya ba’i phyir zhes bya ba’i tha tshig go/

A deluded outlook toward a transitory network (’jig-tshogs-la lta-ba, ’jig-lta, Skt. satkāyaḍṛṣṭi) is the disturbing attitude that grasps for some aspect of the transitory aggregates as being “me” or “mine.” Whether such a deluded attitude is doctrinally based or automatically arising, it can only be congruent with conceptual mental consciousness. Therefore, karmic actions of the mind entail mental consciousness, not sensory, because only conceptual mental consciousness can take the aggregates as being “mine.”

Although it is not explicitly stated, a deluded outlook toward a transitory network is the main component of the ninth of the twelve links of dependent arising, the link of an obtainer attitude (nyer-len-gyi yan-lag). Together with the eighth link, craving or thirsting (sred-pa’i yan-lag), this deluded attitude activates karmic potential for further rebirth.

Sumatishila, An Annotated Commentary (Derge 100B), continues:

As for “(that which causes) further rebirths and” and so on, it is because of this too that (mental) consciousness is to be known as mind (in the phrase “karmic impulses for actions of the mind”). As for “because it is that which causes encounters (with objects during those rebirths),” (it means) since it causes coming upon (them). “Because that (mental consciousness) is taken as the mind with which (a throwing karmic impulse) is congruent” (means) since (a mental consciousness) is that which causes another rebirth in the homogeneous class of a celestial being and so on and (that which causes the mind) to engage with objects such as (appropriate) forms of physical phenomena (during that rebirth).

(Tib.) /skye ba gzhan dang zhes bya ba la sogs pa ’di’i phyir yang rnam par shes pa la yid du rig par bya’o/ /gzhol bar byed pa’i phyir zhes bya ba ni ’bab par byed pa’i phyir te/ de ni sems dang mtshungs pa dang ldan par bya ba’i phyir lha la sogs pa’i ris mthun pa’i skye ba gzhan dang gzugs la sogs pa yul la ’jug par byed pas so/

A throwing karmic impulse (’phen-byed-kyi las), as the tenth of the twelve links of dependent arising, the link of (further) existence (srid-pa’i yan-lag; the link of becoming), is a karmic impulse that propels the mental consciousness into a next rebirth and ripens into that mental consciousness taking as its physical support the body of a limited being in a specific type of homogeneous class of beings, such as a class of celestial beings (gods). It arises from the karmic potential activated by the eighth and ninth links, craving or thirsting and an obtainer attitude.

Accompanying a throwing karmic impulse is a completing karmic impulse (rdzogs-byed-kyi las), which ripens into that mental consciousness taking a rebirth in which it will encounter objects appropriate to ones that can be experienced in that rebirth state. When reborn as a human or celestial being on the plane of sensory objects of desire (desire realm), these objects will be gross forms of physical objects. When reborn as a celestial being on the plane of ethereal forms (form realm), these objects will be subtle, ethereal forms.

Sumatishila, An Annotated Commentary (Derge 100B), concludes his explanation:

As for “The rest is like the words that were indicated previously,” the rest (refers to the rest concerning) mind and mind karma, that was indicated previously. It was indicated like this, “That which affects the mind of an agent (of an action) is a karmic impulse.” Likewise, “Because they are not initial engagers for (subsequent actions of) the body or speech, karmic impulses that are congruent with a mind (mental consciousness) are karmic impulses for (actions of) the mind.” Because here, (in the term “mental karma”) as well, the word “congruent” is not made explicit, it is indicated as a “karmic impulse for the mind” (and not as a “karmic impulse that is congruent with a mind).” As for “suppose (you ask)” and so on, it is raised as a challenge by others.

(Tib.) /lhag ma ni sngar ji skad bstan pa bzhin no zhes bya ba la/ lhag ma ni las dang yid kyi las te/ de ni sngar bstan te/ ’di ltar byed pa po’i yid mngon par ’du byed pa ni las so zhes bya ba ’dis ni las bstan to/ /de bzhin du lus dang ngag rab tu ’jug par mi byed pa’i phyir yid dang mtshungs par ldan pa’i las ni yid kyi las zhes bya ba ’dis kyang mtshungs par ldan pa’i sgra mi mngon par byas pa’i phyir yid kyi las zhes bstan pa yin no/ /gal te zhes bya ba la sogs pas ni gzhan dag rgol bar byed pa yin no/ /

As explained previously, the mental consciousness affected by a karmic impulse for an action of the mind that scrutinizes and decides to commit a certain action of the body is an initial engager of the body regardless of whether a method is actually implemented for causing that action to occur. Such a karmic impulse takes the body or speech as (1) the gateway through which it brings about an action of the body or speech, (2) its sphere of influence and (3) what it directs itself at.

In summary, Sautrantika asserts two types of karmic actions of the mind and thus two types of karmic impulses of the mind that are congruent with mental consciousness:

- One is directed at the body or speech and is the initial engager of them in the context of the three destructive and three constructive actions of the mind – thinking covetously, thinking with malice and thinking distortedly with antagonism. In this meaning, the Sanskrit term cetanākarma (Tib. yid-kyi las) has been translated in this series as an “inciting karmic impulse.”

- The other is not directed at the body or speech and includes the karmic impulse of the mind congruent with conceptual mental consciousness accompanied by a deluded outlook toward a transitory network – a component of the ninth of the twelve links of dependent arising. It also includes throwing karmic impulses and completing karmic impulses for a next rebirth – the tenth link of dependent arising. In this meaning, the term cetanākarma translates simply as “an urging karmic impulse,” “a karmic impulse that is an urging” (it brings about a rebirth), which would also be an appropriate translation of the term that includes both types of karmic impulses of the mind.