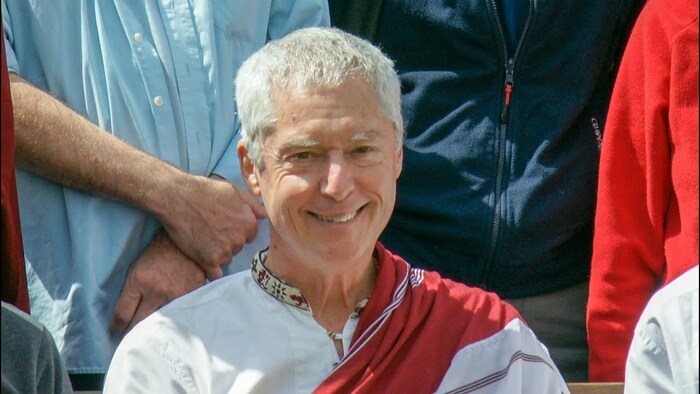

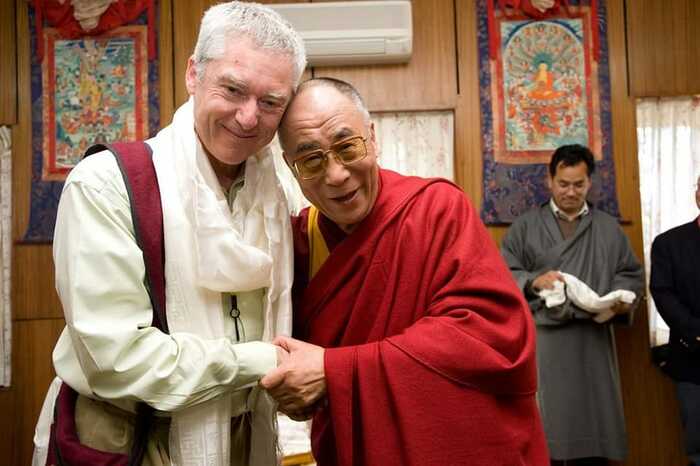

It’s a warm summer’s day, and I’m at Karma Tashi Ling Buddhist Center in Oslo, Norway, to meet one of our generation’s foremost experts on the power of meditation: Dr. Alan Wallace. Surrounded by serene pine forests that stretch as far as the eyes can see, we sit down to discuss his journey from studying science to immersing himself in the Dharma and everything he’s learned along the way.

An internationally acclaimed scholar, author, and practitioner, Dr. Wallace seamlessly bridges the realms of Buddhism, neuroscience, and the quest for a deeper understanding of consciousness. Drawing on his extensive expertise in both science and philosophy, along with decades of intensive meditation training in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, he founded the Santa Barbara Institute for Consciousness Studies, wishing to bring the wisdom of Buddhist mind-science to contemporary society. As a true modern-day explorer of the mind, he has dedicated his life to the pursuit of profound inner wisdom and the synthesis of ancient contemplative traditions with cutting-edge scientific research.

In this interview, we discuss in-depth the current mindfulness movement and problems people face with attention and focus, the power of shamatha meditation, and why we can look to the ancient Greeks for an understanding of true happiness. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: You were studying ecology at the University of California when you decided to travel to India to study the Dharma from Tibetan masters. What was it that drew you to the Tibetans and Tibetan Buddhism?

Dr. Alan Wallace: For as much as I love Tibetan culture, and I really do, that's not what brought me to India or to the Tibetans. And that's not why I studied Tibetan. I did it for the Dharma.

I come from a Christian background, and my father is a theologian. There are many virtues and there is great meaning and a lot of compassion and altruism in the Christian traditions. But there were elements of the Christian doctrine that just frankly didn't make any sense to me. I'm not refuting the religion; it just made no sense to me.

From the age of thirteen, I wanted to be a scientist, having been inspired by a science teacher. I felt that science was factual, authentic, rigorous. I was heading towards a career in environmental studies. The more deeply I went into it and the more knowledge I had in trying to save the environment, I started to realize that finding what the nature of our existence is, what the nature of the mind is, how I can fulfil this inner longing to find greater meaning in life, was not satisfied by science.

Science provides us with an enormous number of facts, while Western religions like Christianity, Islam and Judaism have tremendous meaning. Many people have meaningful lives because of their devotion to their religions and their God and so forth, but what I needed was both together. I wanted to have a view of reality that is authentic, that stands up to the most rigorous empirical and rational analysis. In Buddhism I found a path, a way of viewing reality, a way of living, a way of setting priorities that are profoundly meaningful yet very rigorous, standing up to scrutiny.

For many, the path to Buddhism begins in earnest with taking refuge in the Three Jewels, the first of which is the Buddha. Who is the Buddha?

I’ll tell you a story to answer your question. Once, there was a wandering seeker who saw the footprints of the Buddha. He tracked him like a deerstalker, and when he came upon the Buddha, he was very impressed by the Buddha’s presence. The seeker was so stunned, so filled with awe because I think he might have seen the Buddha rather like what we see in statues and so on. The seeker asked Buddha, "Are you a God?" because he did not seem like an average human being. The Buddha said, “No.” The seeker asked, "Well, are you a celestial being like an angel or something like that?" and Buddha again said, “No.”

He went on, "Are you some kind of earth or elemental spirit?" and the Buddha yet again said, “No.” And then he finally asked Gautama, the historical Buddha, "Are you a man?" and the Buddha said “no,” which was quite a shocker! The seeker was nonplussed, and he asked, "Well, then who are you or what are you?" and the Buddha said, "I am awake." That's the meaning of Buddha: one who is awake.

We live in an age of incessant stimuli and digital distractions and there is this prevailing notion that our attention spans – especially those of children and younger adults – are getting shorter. What are your thoughts on this?

There is a sense of restlessness, ill-at-ease, and an addiction – and I mean literally an addiction – to stimulation. We have this issue of children growing up in the world that my generation and now your generation is creating for them. I have an 11-year-old grandson. He didn't create the world that he's living in right now, so he's not responsible for it in any way, but he's immersed in it. When you're living in a large city like Los Angeles, Berlin or anywhere else like that, clearly it’s not the same as living almost anywhere 100 years ago.

In terms of just the sheer amount of information, the stimulation, the multitasking that's considered basically the way you have to live, I am sure that it does really disintegrate, or create an ongoing perpetual turbulence, an addiction to doing and doing, an inability to sit quietly and simply be present.

And I think there's a lot of evidence for that, because even in elevators we'll have music! You go to a doctor's office, and they know they can pull out 6-month-old magazines and people will still read them, because they just don't know how to sit quietly. And if that's true of my generation and now you're one generation younger, and my grandson another generation younger, there is an issue. It is a problem.

A very large percentage – I can't remember what it is – of teenagers now in the United States are clinically diagnosed as having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and in our materialistic, reductionistic, and sometimes flat-out idiotic civilization, they're primarily given drugs, rather than look at the underlying causes.

So, young people, children, adolescents, are they more scattered than people of my generation when we were children? I think probably so, but then it's also true that if my grandson sits down with his cell phone or an iPad and is playing video games, he's going into samadhi in those video games, and he can remain for one or two or more hours. It’s the same with watching a movie or doing things on the internet and so on and so forth.

So, they can stay focused on what they're really interested in and what they enjoy, but then can they be equally focused when it's learning multiplication tables, or learning spelling, or just having to listen to somebody, learning something they're not terribly interested in?

Because attention is not simply being able to attend to what we find entertaining. It's more like a muscle, and that is, if you've developed your attention skills you should be able to use that for sports, for mathematics, for preparing a good meal, for having a conversation, and for sitting quietly and observing your own mind. If all your attention is good for is that which you find very stimulating, as it gives a sense of arousal and entertainment, that's a poor substitute, and that's not going to have much mileage when you need to get a job, and maybe your job is not that interesting.

We all know that meditation offers a wide range of benefits, among them the strengthening of our attention and focus. Still, so many people struggle to establish a daily meditation practice. We come up with all sorts of excuses – work, family, social life, gym. As an expert meditator, what is your advice?

Everybody's busy, so get over it! We're all very busy, and human beings have always been equally busy, because everybody's doing something for roughly sixteen hours a day. And that means we're all busy. By and large we're busy with what we value, and we don't have time for what we don't value. If people are struggling just to exist – roughly half the human population is in poverty or near poverty – what’s going to be occupying their minds is simply making a living.

But many of us, including myself, don't have to spend every waking moment just to get food, clothing, and shelter. So how do we fill our leisure time? We fill it with what we choose, with what we prioritize. Some people want to make a lot of money, they want fame, they want influence, they want prestige, they want greater status. That's going to take up a lot of time. That's where their priorities are, so if they say, "I'm too busy for meditation," all I say is, "You simply prioritize something else more than meditation."

So, it’s a question to ask ourselves. Why would anybody prioritize meditation? Why take out five minutes, let alone an hour? When you are busy, you've made a choice and you're busy with what you prioritize. Well, if you are not happy with your choice, make a new one! So, if you have only five minutes to cultivate your mind, I just have to say you're not taking your mind very seriously. You're taking everything else more seriously – you’re taking your teeth seriously because you spend five minutes brushing your teeth, and you take personal hygiene seriously because you shower for 20 minutes!

We do that without really thinking, because we value our physical health, keeping clean and being socially respectable. Well, if physical hygiene is important, how about psychological hygiene? If all you can manage is five minutes, check your priorities. Do you really want to be happy? Are you finding the contentment you seek in the way of life you're already following? If so, then I rejoice for you, but if you're not content: consider giving more than five minutes.

Still, whatever you have, whether it's five minutes, 20 minutes or twelve hours a day, a practice that can be helpful quickly is to learn how to calm your mind. Get out of the default mode of rumination, of distraction, of restlessness, feeling ill-at-ease, and learn how to quiet down the mind. A way of doing that is mindfully attending to the in-breath and the out-breath, releasing and relaxing. Calm down and come to some inner silence, a kind of composure. Be present and you may find that's very helpful. You might find it even addictive, and that may not be a bad thing!

On this topic, you’ve been teaching shamatha for over 40 years with your workshops and writings, and you always remind us that it is an indispensable part of the Buddhist path. What actually is shamatha?

Shamatha is a Sanskrit term, it’s samatha in Pali, and the word literally means quiescence, tranquillity, serenity, calm, calm presence or peaceful presence. What shamatha refers to is an array of methods that are designed to develop your attention and metacognitive skills, your attention skills, so that whatever you wish to attend to, whatever it may be, you can do so without tightening up, getting restless, getting constricted, stressed-out, while maintaining a sense of ease and looseness. You can maintain continuity of attention and vividness of attention. In order to develop your attention skills through the methods of shamatha, you must also be honing your metacognitive, or introspective skills, so you can recognize when your mind is becoming distracted or dull.

Shamatha is quite universal. Contemplative traditions around the world, without using the term shamatha, recognize that you've got to learn how to really focus and stay focused in any type of contemplative practice. Buddhism is exceptionally rich in this regard. I regard it as a contemplative technology. It entails no belief system, no commitment to any ideology or institution or any group. It is simply a way of refining the mind in very specific ways that make the mind serviceable, flexible, supple, malleable, and useful for all types of activities. With shamatha, you'll be able to do anything you're doing better: as an athlete, a businessman, an artist, a scientist, a mother, a spouse.

Apart from its benefits for focus and as a foundation for insight meditation, can we expect any physical effects for our bodies? Are there any signs that our shamatha practice is deepening?

As long as we're alive, our minds are embodied minds. They're profoundly entangled with, and interrelated with, not only the brain but the entire nervous system, the entire body. In turn, the body is related to the environment. Therefore, if we're going to be training the mind, if we're going to be cultivating or refining the mind, there will be correlated shifts in the body in terms of one's nervous system if you use Western terminology, or a shift in “prana” if we use Asian terminology.

In the course of shamatha practice, as the mind becomes more supple, more light, more buoyant, filled with a greater sense of well-being, in fact you do discover that the body is also shifting – stress starts to decrease, and a sense of malleability, pliability, pliancy, suppleness, and buoyancy arises with this practice.

I've been teaching this practice for a long time, and often I hear people who are practicing fairly intensely, like six, seven, eight hours a day say, "Oh, I had this backache," or, "I had this frozen shoulder,” and, “I haven't even been doing yoga, but I'm doing a lot of shamatha and find my frozen shoulder is now melted and it feels really good.” Or they find they are much more supple, or their body overall feels much better.

Thus, shamatha is enormously helpful. And in terms of healing and balancing, it has wonderful effects both psychologically and physiologically.

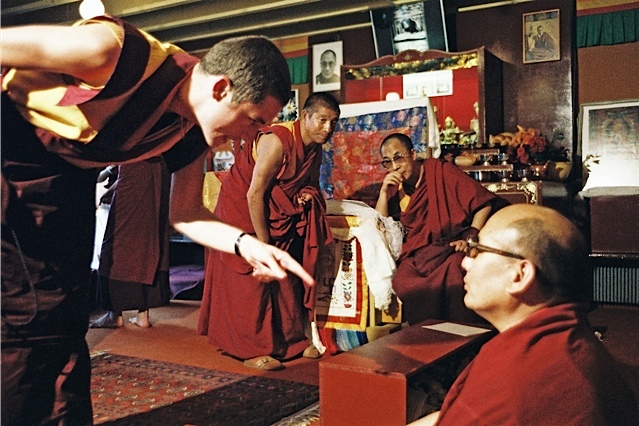

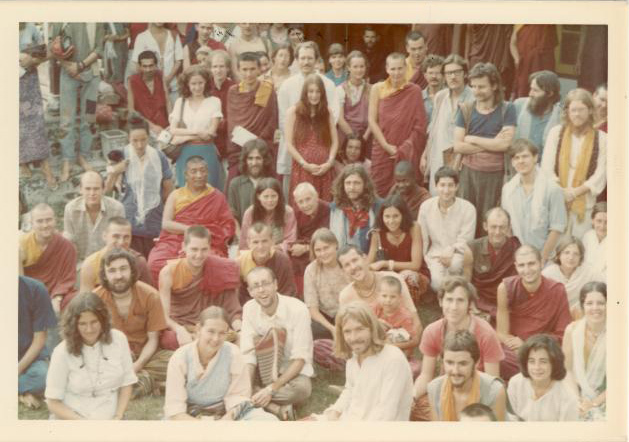

You studied Buddhism amongst Tibetan masters in India and lived as a Tibetan Buddhist monk for a decade. Since your return to the US, you have been teaching Buddhism in the West. Do you ever question if the Tibetan Buddhist teachings can be authentically transposed to Western cultures? Do these teachings from Tibet, transferred to other countries, remain authentic “Tibetan Buddhism?”

I do not think we should worry about whether we as Westerners can be "real Tibetan Buddhist practitioners." We have these terms, which are perfectly good terms: Tibetan Buddhism, Mongolian Buddhism, Zen and Chan and so forth. In a way, nobody but a Tibetan can practice Tibetan Buddhism, as in really nobody but an American can practice American Buddhism!

I would often say that I was born at the age of 20, because that's when I started immersing myself in Buddhist culture, living in monasteries and so forth. But, of course, that's not true. The 20 years of me living in the West before I went East don't evaporate. They have, of course, a very deep influence on you for the rest of your life. I know people like Matthieu Ricard and Tenzin Palmo, who've lived for decades in India and Nepal, and they're outstanding practitioners. But Tenzin Palmo is not Indian and she's not Tibetan, and Mathieu Ricard is still very French. Even when he speaks Tibetan, it's with a French accent! It's inescapable. And why not? Is he a good practitioner, an outstanding practitioner? Definitely. Tenzin Palmo – I hold her in the highest regard. But they're not just practicing Tibetan Buddhism. In her case, it's English Tibetan Buddhism. Matthieu, definitely French Tibetan Buddhism, and inescapably mine is American. Well, I've lived many years in Europe so perhaps it's kind of Euro-American Tibetan Buddhism.

And there's no problem with that, and we should feel at ease with that, because 1,200 years ago when Buddhism came to Tibet, it took a while until they started saying, “We're practicing 'Tibetan Buddhism'.”

They were practicing a foreign import that gradually, over time, took on more Tibetan characteristics, just as Buddhism here is taking on characteristics from the West. Some of these characteristics are how Buddhism is really getting diluted, commercialized, commodified, polluted, contaminated with all kinds of rubbish that we're throwing into it. On the other hand, Buddhism is also taking on a new evolution that is still authentically Buddhist, but is also authentically in the 21st century, not just trying to emulate Tibetans living in the 19th century.

How do you view the current mindfulness meditation movement in the West?

There is this great mindfulness movement now, and I think that's a nice way of saying it. Some people call it a mindfulness “craze,” but I don't want to be that uncharitable, because clearly a lot of people are getting benefits. It's become very popular, it's in the media, it's being scientifically studied, and its practical applications in the business world are being very much highlighted.

It looks, however, like it is something of a fad, and it is also coming under some severe criticism by people who are not unintelligent. I've read one article after another saying, “This is not just a bowl of cherries – this has some serious downsides to it.” And, so, the question we can ask is, "Well, what comes after mindfulness?" My answer is, “Buddhist mindfulness!”

Because, what we have right now is a definition of mindfulness that has never been Buddhist, is not Buddhist now, and will not be tomorrow. Just calling something Buddhist doesn't make it Buddhist, and if you make up your own definition of mindfulness that is nowhere to be found in any Buddhist tradition, or any of the teachings of the Buddha himself, then it's illegitimate to call it Buddhist just because you would like to or maybe because it's a good marketing tool.

There is now this definition that mindfulness is a moment-to-moment presence of mind, an attentiveness to whatever is arising in the field of your experience and attending to it closely, but without judgment. It’s just being present with whatever is happening here, and whatever it is, just being present. That's a nice definition! But show me any source older than 50 years old in the Buddhist tradition that says that's the definition of mindfulness, and I can tell you it is not to be found because it's not a Buddhist definition. It's a definition that's inspired by some people who like Buddhism, or it's inspired by extremely watered-down versions of vipassana, but I can tell you the Buddhist definition of mindfulness is entirely different.

The Buddhist definition is not sectarian. It can actually be found everywhere by scholars who know how to study well. The Buddhist version of mindfulnesess is: I'm now familiar with you. For example, every time I look at you, I'm not shocked, "Oh, who are you?!" I maintain a flow of awareness of you and maintaining that flow of attention – it’s voluntary – I’m focusing on you, your questions, your body language, your facial expressions.

I'm bearing you in mind, I'm holding you in mind, I'm sustaining this flow of voluntary attention without distraction, without forgetfulness. That's mindfulness. I'm being mindful of you.

Now, mindfulness can be retrospective: I remember my address. That's retrospective mindfulness, because the core Buddhist meaning of mindfulness is recollection, as in "bearing in mind." Am I bearing in mind my address? If I'm practicing mindfulness of breathing, I'm bearing in mind the in-and-out flow of the breath from moment-to-moment, but I can also bear in mind that I need to leave here at six o'clock to go off and give a lecture. I need to be ready at six to go out the door, and I'm going to bear that in mind. That's retrospective memory.

Buddhist mindfulness is discerning mindfulness in which we recognize which ways of speaking, physically behaving and using the mind are wholesome, which are conducive to my own and others’ well-being, and conversely which are afflictive, toxic, harmful to myself and others. Buddhist mindfulness entails discerningly recognizing, "This is wholesome, this is unwholesome," and then doing the sensible thing: following that which is wholesome, and then releasing as much as you can the unwholesome.

That's not being judgmental, it's being wise and discerning, and often the wisdom and discernment are completely left out in the modern mindfulness movement. Therefore, the modern mindfulness movement, which leaves out ethics, which leaves out the Buddhist way of life and the Buddhist worldview, is not actually Buddhist at all.

Your book Genuine Happiness: Meditation as the Path to Fulfillment explores what Buddhist meditation and science have to offer us in the pursuit of happiness. In the book, you use terms such as “hedonia” and “eudaimonia” from classical Greek philosophy to explore what happiness is. Can you explain their connection to the Buddhist notion of happiness?

To link it to our culture, to address the question of what happiness is, we can go back to Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. These very wise ancient Greeks made a distinction between “hedonia” and “eudaimonia.” Hedonia is not something vulgar or coarse, but a kind of pleasure we get that comes in response to some pleasant stimulation. It could be seeing your children grow up happy, it could be having an ice cream cone, it could be enjoying beautiful weather, it could be enjoying a difficult problem in mathematics, enjoying all kinds of things, but you're enjoying them because there's something there that's bringing you enjoyment.

That's one type of happiness. And to show that this is not trivial – the kind of happiness you have by having enough to eat, by having clothing, shelter, medical care when you need it and education, that's all hedonic, and we all know there's nothing trivial about that.

But then, we can ask, “Is that all there is to happiness?” And the ancient Greeks and many other great, wise people of the past including the Buddha, and many others in the East and the West, have highlighted that there's another whole dimension or domain of happiness, and the Greeks called it “eudaimonia.”

Eudaimonia is genuine well-being, something that comes from within. It's something we bring to life, rather than get from life, and it operates on different dimensions. We can have it if we lead an ethical way of life, a life that's oriented around the principles of non-violence and benevolence. That's basically all of Buddhist ethics, and many people can relate to that. If we just stop right there, that's good. If we really orient our lives around these principles, then there's certainly a sense of well-being.

The Buddha called it the joy of having a clear conscience. It is a joy. It's a sense of ease, a sense of contentment that my presence on the earth here has not been of harm; in fact, I think I've done some good. And even if I never meditate for a moment, that's already good. That is one dimension. There's the other dimension of eudaimonia that comes from cultivating the mind, cultivating the heart, cultivating powers of attention, samadhi, cultivating wisdom, cultivating compassion, and so on.

Even when you're in solitude, maybe even years of solitude, your mind itself is found to be a wellspring of happiness, of eudaimonia. And then finally, there is a sense of joy, even bliss, by experientially knowing the nature of reality: who you actually are, what's the nature of awareness, what's the nature of reality. The great sages of history have said the deepest form of happiness is the happiness of knowing reality as it is.