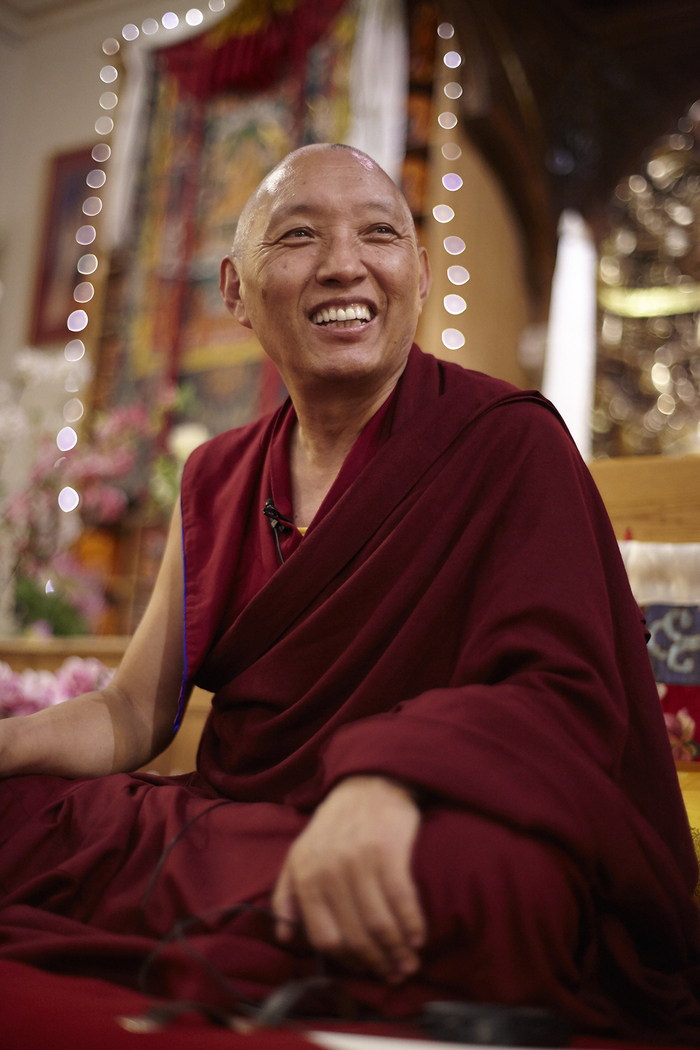

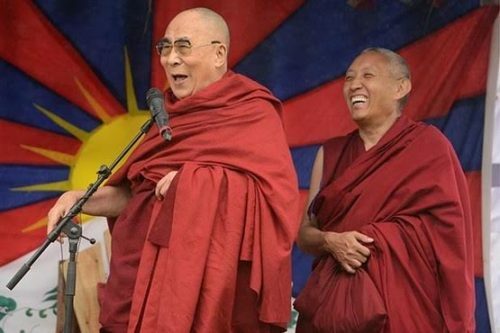

I’m feeling a little nervous, although I shouldn’t be. I should feel very at home, because I am in the place where my very own Buddhist journey started, and I’m about to meet the very teacher whose classes propelled me into the life I lead today. I’m at Jamyang Buddhist Centre in London, and I have an appointment with Geshe Tashi Tsering, who has been the resident teacher at this cherished Dharma center for over 20 years. And I’m lucky to catch him, as he is about to depart the UK for India, after accepting His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s invitation to become the Abbot of Sera Mey Monastery.

Born in Tibet, Geshe Tashi Tsering became a monk at the age of 13 in India. He holds the Lharampa Geshe degree from Sera Monastery, as well as a Master’s degree in social anthropology from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. The creator and original teacher of the two-year “Foundation of Buddhist Thought” course and the author of several books on Buddhist philosophy, psychology, and tantra, he is a widely beloved leader of the British Buddhist world. So much so, in fact, that in June 2019, he was awarded the British Empire Medal for services to Buddhism in the UK by Queen Elizabeth II. A learned scholar and a deeply experienced teacher, he is known for his humility, warmth, approachability, and ability to relate Buddhist teachings to lay people’s lives. And I, for one, am deeply grateful to him for his impact on my life.

In this interview, Geshe Tashi speaks about his optimism for the survival and future of Tibetan Buddhism outside Tibet, the importance of moving beyond simple mindfulness meditations, and common misconceptions about various essential Buddhist concepts.

Study Buddhism: In a society increasingly defined by external pressures and the pursuit of immediate gratification, how do you believe the ancient teachings of the Buddha and Buddhist practices offer a valuable counterbalance, encouraging individuals to find lasting happiness and fulfillment within themselves rather than relying on external validations?

Geshe Tashi Tsering: The basic teachings of the Buddha and the subsequent commentaries written by Buddhist teachers are still extremely relevant to this 21st century. Particularly to the 21st century, which, as you said, is extremely pressurized to have an emphasis on external needs. People are very stressed out by these kinds of social pressures, and pressure from big companies and so forth. Actually, our external needs are very much surface, temporary, and not very long-term.

So, the teachings of the Buddha and the associated Buddhist practices counteract or at least slow down that kind of need for some external thing or event to make ourselves happy, fulfilled or to feel, "I'm great!"

With the Buddhist teachings, eventually we look at more resources within ourselves, and through this we make ourselves feel confident, feel good, feel happy.

Reflecting on the evolution of Tibetan Buddhism in the West over the past few decades that you’ve taught, can you elaborate on the challenges you’ve encountered along the way? Moreover, how do you see the current trend of laypeople actively engaging with Buddhism, and what impact might this have on the future sustainability and integration of Tibetan Buddhism within Western societies?

Tibetan Buddhism in particular is very young in the West, it has been around for less than 50 years. While some Tibetan texts were translated into German, French and also English, establishing Buddhist centers and study programs, we can say, are still a very recent phenomenon.

When I first came here to London over 20 years ago, I thought, "OK, now I'm the resident teacher, I need to set up a structured study course." When I explored what there already was, there was very little. Throughout Europe, there was only one in Germany, in Hamburg, with Geshe Thubten Ngawang, who ran a structured study program. Otherwise, there wasn't a single study program! I was a little bit shocked.

Even now it is difficult to say whether Tibetan Buddhism is even well-established in the West. Many of the important texts are still not translated into English. Of course, there are more compared to the 1990s. The large majority of people who come to the centers, like Jamyang Buddhist Centre in London, are laypeople. They have their own ordinary lives; they can be married, single, have children, have work commitments, family commitments, but still, they come. They come to the center, week after week, month after month, year after year, to study Buddhism, meditation, and to join retreats.

In the future, if the trend continues in this way, the survival of Buddhism has a good outlook. Why do I say this? Because then Buddhism is taking hold within the lay community, the general community, and is not isolated to a small, specialist lifestyle like in a monastery. That kind of isolated, specialist lifestyle is not very stable anymore. When the community changes, when society changes, that lifestyle can be wiped out within a few years. It happened in Tibet. Therefore, it gives me a lot of positive hope that Buddhism will survive and continue, and the teachings of the Buddha will serve the wider community in the West.

In observing the growing interest in Buddhism, mindfulness, and spirituality as a whole among Westerners, what trends have you noticed? What is it that people are looking for?

When I came to the West it took quite some time for me to understand why Westerners are interested in Buddhism. I think it's still the case that there is some form of spiritual vacuum. Many people in the West do not find their forefathers' religions, such as Christianity, Judaism and Islam very relevant. But still, they feel they need some kind of spiritual or moral compass to lead their lives in a more constructive way.

When I first came here, even in English there were very few books. Now, there are plenty of ways for people who wish to explore different types of spirituality. They can Google them 24 hours a day, with millions of sites they can visit. This is something that we can say is relatively new.

In the last few years, the mindfulness movement has grown quite widely and rapidly. Not only mindfulness, but in general, meditation has become very fashionable. Many Hollywood stars and people who have some kind of name or fame have shown interest in meditation. Many of these people are looking for a quick fix to fulfill their needs. And it seems that Buddhism is one of the many solutions that people come to, to find their quick fix.

As you just mentioned, there are now uncountable sources of information – some more valid than others – for people to turn to. Are there hidden dangers to this form of getting acquainted with the teachings?

No doubt these days more people are turning to Buddhism, and how they approach Buddhism is quite different than when I first came to the West. Then, if you were interested in Buddhism, either you'd read books, or you'd go on a university course, or go to the Buddhist centers.

Nowadays, you can listen to and watch livestreams every day, from different teachers and different traditions. This has many positive results because if someone is really interested in studying Buddhism, they have easy access, which wasn't the case in the past.

At the same time, there are shortcomings to this, because people think that visiting a website or watching a livestream or just following a few simple mindfulness meditations is the extent of the teachings of the Buddha. And this isn't the case. The teachings of the Buddha are very wide, very profound, and it takes a long time to really gain their long-lasting benefits.

For instance, let’s look at mindfulness. Mindfulness-based stress reduction is extremely popular and very helpful, but quite often people believe this is what the Buddha taught, and that is all there is to the Buddha's teachings. But that's not true.

Therefore, the meditation they do is just scratching the surface. There's nothing that goes to the depths of the Buddha's teachings. There's nothing wrong with saying it comes from the Buddhist tradition or the ancient Indian spiritual traditions, but it is important to be clear that it is a very basic, simple thing from the teachings of the Buddha. It is not the full thing.

So, I usually advise people to try to understand that there are very profound, very sophisticated meditations to be learned within the teachings of the Buddha.

For as long as I’ve known you, to me at least you’ve been a beacon of peace and serenity. What is your advice on overcoming stress and anxiety?

The best way to reduce meaningless worries and anxiety is to make ourselves feel more confident and happier through our own inner resources. We need to cultivate a sense of stability within ourselves.

We can develop trust that, within ourselves, there are these amazing mental states and abilities – the ability to understand, the ability to experience not just our own feelings and thoughts, but also other beings' feelings and thoughts.

Also, we need to know that, by nature, all things have ups and downs. Awareness of this is very important. Right at the beginning, when things are going very well, be aware of this truth: “Yes, things are going well at this time, but one day, it will change.”

That is the teaching of the Buddha, what we call the nature of impermanence. Understand the nature of impermanence, that things are subject to change. Every now and then, try to be fully aware of that nature of impermanence. Even though things might be going very well, and we don't like things to change, change is the nature of things and events. Of course, we should do our best to continue our good life, but it is just reality.

If you go and look at museums, you see pictures, photos and paintings of the famous and successful, but now they're all gone. They had to leave everything behind. That is the teaching of the Buddha. It's very powerful and helpful to be fully aware of the nature of impermanence, that things and events are subject to change.

This is very powerful advice. Similarly, when we’re perpetually bombarded with images of friends and strangers on holiday and their achievements, how can we deal with feelings on envy?

Actually, it is useful and helpful to acknowledge the people you feel envious and jealous of, and understand that these people are also living beings, sentient beings. Although externally they may have things that you envy, they are also here within samsara, within cyclic existence.

Here, I'm not suggesting that you should feel great that they're also stuck in the cycle of suffering. Not in that way! But the understanding is very useful. Because for those people who have all those good things, those amazing things, instead of envy we should try to rejoice and appreciate. But for us it's difficult to have that kind of rejoicing and appreciation, and it's mainly because we haven't understood the full picture of the things that they have and the whole nature of the person who possesses the things.

If we have a better understanding of the person's entire nature, particularly from the Buddhist point of view of being in samsara or cyclic existence, and of the possessions that he or she has, a car or whatever, you'll see that they're also samsaric things. They also have the potential to bring a lot of pain and difficulties. If we have this understanding, I don't think we'll have envy or jealousy.

So, instead of feeling envious of others for having that brand new car or winter holiday, it seems as though we should have compassion. Could this form some kind of basis for the development of compassion for others?

Many of us, when we express compassion or love toward others, we don't have a good understanding of the suffering, pain and difficulties that other beings are going through. This is because we ourselves have not understood suffering very well in relation to our own life. To develop compassion and loving kindness, we first have to understand the sufferings, pain and difficulties that we ourselves experience. Our own suffering, our own pain, our own difficulties should be understood in more depth and detail, then we can try to apply that understanding to others.

So, the Buddhist way to approach cultivating compassion and loving-kindness is first to have love and compassion for oneself. Then, through that understanding, if we apply it to others, it will work, and there won’t be a strong attachment to others at the same time.

What does taking refuge mean for our daily lives?

Sometimes people treat taking refuge as though you are becoming something. That's not the case, really. It is teaching you how to live according to the teachings of the Buddha. Taking refuge in the Dharma, in the teachings of the Buddha, can be summarized into three main topics: concentration, living an ethical life, and cultivating wisdom. So, taking refuge in the Dharma means living with these three things in our daily lives. Taking refuge in the Three Jewels will benefit your everyday life.

What should be our main questions or considerations when we decide to take refuge?

In my case, I was born into a Tibetan family, so I was more or less “born as a Buddhist.” That's the culture. But taking refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha is not something that we can take as just part of our culture. It needs a deeper, clearer understanding of the teachings of the Buddha, initially by listening to others and eventually through one's own contemplation and reflection. Without these, taking refuge in the Three Jewels might just become a ritual.

There are two questions that need to be answered, very clearly and in-depth. The first question is, "Why do I need refuge?" I have a car, I have a house, I have a job, I have all these things. On top of these, why do I need refuge? Individuals have to contemplate and reflect on this and find the answer.

The second question is, "In whom am I taking refuge?" Am I taking refuge in this person who is leading the refuge ceremony? Or am I taking refuge in something or someone "up there," whom I'm never going to meet? To answer this question, individuals need to know the Buddha and the qualities of the Buddha, the Dharma and the qualities of the Dharma, the Sangha and what are the qualities of the Sangha.

It is very similar if you're going to buy things you need. You will do thorough research about the quality, quantity, price. It is exactly the same!

There are a number of key Buddhist concepts that can cause confusion when interpreting their meaning, maybe due to language barriers. One such core Buddhist concept is renunciation. Is it just about giving up worldly pleasures, possessions and pursuits?

The Buddhist concept of renunciation is not physically giving up everything. It is mentally reducing grasping, craving, clinging to some of those things and events, mainly to those that don't have that much meaning. It is entirely within ourselves to cultivate and nurture some kind of mental strength, a determination not to give in to strong craving, clinging, grasping to meaningless affairs and things and events.

It is perfectly possible for people who train their minds to be able to have lots of possessions, but still not have that kind of grasping. So, it's not just about running away from all the material things or attractive things. It is the mental cultivation of strength not to give in to attachment, grasping and craving.

How can we reduce such grasping in our everyday life?

Often it is said that the teachings on emptiness are the essence of the teachings of the Buddha. Although the teachings on emptiness are interpreted in many different layers and levels, the basic reason emptiness was taught by the Buddha is so that we don't grasp onto things and events, we don’t grasp at our own identity, our own status, good feelings, possessions. Because grasping is the key element that follows with our unpleasant, unhealthy emotions, thoughts and actions. The teaching of emptiness is there to reduce grasping in our everyday lives.

Tibetan Buddhism has a strong element of advanced Vajrayana practice and teachings. When is an individual “ready” for tantra?

Although there are other Mahayana Buddhist traditions, such as the Korean, Japanese and also Chinese traditions, that have some form of Vajrayana practice, the four classes of Vajrayana practice and teachings, as far as I know, are found only in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition.

If an individual is interested in practicing Vajrayana in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, it is very useful to set the ground well, to build the foundation well. Without the foundation, you can't build the walls and the roof. The foundation is the teachings that the Buddha taught in the Theravada tradition.

Then you need an understanding of the teachings that the Buddha taught in the Bodhisattvayana, such as bodhichitta and an understanding of emptiness. When these foundations are well-laid and prepared, then you don't need to ask, "I'm interested in Vajrayana teachings and practices, am I ready to go and seek them?" Your understanding of the teachings and the practices will lead you to realize, "Okay, now I'm ready." And that's the best way to make the decision instead of asking some a guru, "Can you do an observation for me, should I take this deity’s initiation?"

When people do this – go and ask a guru – I am quite surprised because while Westerners are, generally speaking, very much science-based, to just go and ask for an observation about whether to take an initiation or not is a very naive way to approach Vajrayana.Individuals need to nurture themselves through the teachings, through the practices, then they will know whether or not they are ready. They'll know if they even need Vajrayana practice or not.

Purification is a central element in Vajrayana practice. What is the meaning and significance of purification?

The practice of purification is found not only in Buddhist traditions. Almost all of the world's major religious traditions have some form of purification, confession and so forth.

In Buddhist Vajrayana practices, there are sections of the teachings and practices that focus on purification. The first, main step of purification is to acknowledge the mistakes we’ve made, whatever the circumstances. Because of our own faulty knowledge or without that but due to the strong influence of attachment, aversion and ignorance, we make mistakes. We commit unpleasant actions with our body, speech and mind.

The second thing is to have determination. Mistakes have been made in the past, but in the coming days, months, and years, I will try not to make such mistakes again. That determination is very important. When we have this acknowledgement that mistakes are made and a determination not to do similar things again, then we can apply what we call the antidote.

For example, if you've noticed that out of anger, you've done something very unpleasant to others, the actual purification is then to develop a strong sense of love toward them. Cultivating that kind of mental state is the actual purification.

People often have a concept that during purification they do some recitation or visualization or prostrations, and the negativities are in a very dark, strange, unpleasant form, but after these purification practices this very dark force or whatever is completely gone. It's not like that.

I will give an example of what purification is. You have a garden, and spring is starting. You want to sow some seeds for the vegetables for the summer and autumn, so you get packets of seeds and sow them in the soil. But a few weeks later, you look at the packet and you realize you've actually sowed seeds for winter vegetables, not summer and autumn ones. So, what can you do? You don't take care of them, you don't water them, you don't add fertilizer. So, what's going to happen? Even if they grow, they won't grow that much. And if you stop watering them, they will just stay as a seed.

Purification is similar in this sense. When you stop doing the same unpleasant things again and again and again, what has already been done won't have the full strength to bring results. That is the meaning of purification.

Geshe Tashi, thank you so much for your time and clear explanations of such deep Buddhist concepts. We wish you every success during your role as abbot of Sera Mey Monastery.