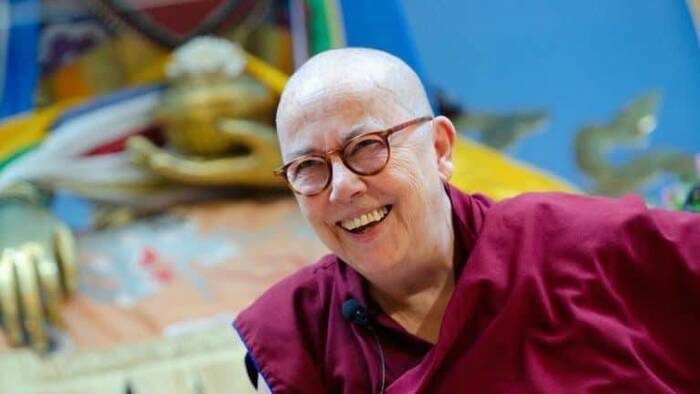

In a tranquil corner of Helsinki, Finland, I’m filled with a sense of anticipation as I prepare to embark on a journey into the world of Buddhism with a remarkable teacher, Venerable Robina Courtin. Venerable Robina is not your typical Buddhist nun; she's a dynamic and passionate individual, renowned for her captivating no-nonsense talks and her mission to make Buddhist wisdom accessible to people from all walks of life. As we sit down for an interview, it becomes immediately clear that I’m in the presence of someone who has dedicated her life to unraveling the profound teachings of Buddhism.

Venerable Robina's path to becoming a Buddhist nun began in the bustling streets of Los Angeles, where she was a self-professed "real-deal hippie" during the 1960s. Her quest for answers to life's deepest questions led her on a journey of self-discovery, ultimately leading her to Lama Yeshe, a Tibetan Buddhist Lama and a pivotal figure in the spread of Tibetan Buddhism to the Western world. Lama Yeshe's guidance left an indelible mark on Venerable Robina, and one particular insight she learned from him serves as the cornerstone of our conversation: "Practicing Buddhism equals becoming your own therapist."

Our dialogue delves into the profound implications of this statement. We explore how Buddhism offers not just a set of religious beliefs, but a practical framework for understanding the human mind and emotions. Venerable Robina sheds light on the transformative power of Buddhist practices, which empower individuals to navigate the complexities of their own minds, heal emotional wounds, and cultivate inner peace and well-being.

But our conversation with Venerable Robina Courtin doesn't stop at self-therapy; it ventures into the very essence of Buddhism itself. We uncover the radical nature of the Buddha's teachings and explore the notion that the Buddha was not merely a spiritual figure but also a revolutionary thinker who advocated for self-empowerment, compassion, and a profound understanding of the human condition.

Furthermore, we dispel the common misconception that Buddhism is a passive or detached philosophy. Venerable Robina passionately explains how Buddhism is, in fact, far from passive. It is a call to action, an invitation to engage with the world, and a framework for creating positive change in our lives and society at large. She highlights the dynamic nature of Buddhist practices, challenging the notion that Buddhism is merely an escape from the world’s problems.

As we dive deeper into these topics, Venerable Robina Courtin offers us insights that can resonate with seekers of truth from all backgrounds. Her eloquence and passion for these teachings shine brightly, making this interview in Helsinki an enlightening journey into the heart of Buddhist thought and practice. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: Your teacher Lama Yeshe published a popular book entitled Becoming your Own Therapist, and you’ve given many talks on the same subject. Could you explain the essence of this book and tell us how the Buddhist teachings can serve as a form of therapy?

Venerable Robina Courtin: “Being a Buddhist is being your own therapist," as Lama Yeshe put it, means to recognize that what goes on in the mind is the basis of your happiness and suffering. So, if you want to be happy, you change your mind.

To be your own therapist means that we have to learn to distinguish between all the thousands of thoughts that are flying around in our head from the time we wake up to the time we go to sleep. We are mostly ignorant of 99.9% of these thoughts. We only feel the symptoms of them when they hit our body, when we have serious emotions, because we don't look deeper. The Buddha's view is so simple: my suffering comes from these neurotic states of mind. They are the source.

There's this primordial misconception of a self that is so ingrained within us that we can't even give it a name in our culture. It is a bottomless pit of neediness, of feeling separate, of feeling dissatisfied. That's the most basic energy of attachment. When attachment doesn't get what it wants, which happens a thousand times a day, it’s called aversion. The strong aspect of aversion is anger, and the internalized version is depression. The way this works is so primordial, so nuanced, that we'll never begin to see it until we start getting some focus.

By stepping out of our head, and developing concentration, we then start to listen to, unpack, and unravel our own conceptual process which is informing our emotions. This is the actual job of being a Buddhist, which is not that easy. Then we're going to notice that we all run to the negative side. We run instantaneously to, "I'm no good, I'm not good enough, I haven't got enough, he doesn't love me enough." No matter how much we get, it's never enough! That's the default mode, and that’s the irony of ego. So, we've got to consciously change this process, which is not an easy job, but that's what we're doing, or at least trying to do.

You just mentioned that the source of our suffering, from the Buddhist point of view, is our own neurotics states of mind. Could you elaborate further on these states of mind and offer insights into some of the methods to overcome them?

When we understand the Buddhist view and Buddhist workings of the mind, we see that there is a clear distinction between the positive parts of me and what they would refer to as my neurotic, unhappy state of mind, which is a source of my own pain, and therefore the source of my problems with others.

The key thing that the Buddha is saying is that what goes on in our minds is the key factor in determining happiness and suffering. This is a massive point, because it's not what we believe. I believe you are the cause of my happiness, and you are the cause of my suffering, and what my mother did, and what my father did, and what happened at school, and all these external events.

But the Buddha says, "No. It's what goes on in your mind.” Those external things play a role, of course they do, but the key thing is what goes on in the mind. But knowing what goes on in our mind is not an easy job. Often, we don't even notice it until it's vomiting out the mouth! We don't even notice we're depressed until we can't get out of bed one morning. We don't pay attention until it's too late. Our emotions are the tip of the iceberg. They're informed by elaborate conceptual stories deep in the bones of our being. We need to have some space to start to listen to those, to have some form of inner inspection. This takes immense courage. These stories are so deep down, they're literally unconscious, so we have to go to that level.

That's why we have to learn meditation skills such as "concentration," not to make all the pain go away, which is one of the big misconceptions about mindfulness meditation, as though it's an alternative to a pill. The reason to go and get focus is so that we can listen to all the crazy stories deep down in there that we don't notice normally. Normally we have two options: vomit it all out or live in denial. We don't know any other way.

But with the Buddhist method, this marvellous, intelligent method, we become deeply familiar with the workings of our own thoughts and feelings, and then we work with them. We can learn to work with our minds and control our mind. It's amazing! The Buddha's view is so outrageous, so remarkable and radical, but we just don't notice it because we think of it as “religion.”

So, we need to get to know our mind and understand the mess deep inside – but then how does this lead to happiness?

The Buddha is saying that whatever goes on in our mind, every second, whether it's intellect or feelings or emotions or unconsciousness, is the main factor that determines whether we're happy or suffering. The whole framework of Buddhism is in terms of happiness and suffering. We look at ourselves and we'll go, "Yeah, I want happiness. No, I don't want suffering." And the Buddha says, "Great, well I've got some methods for you to change the way you see the world!”

Because right now, being a "samsaric person," you're living in la-la land. You think your mother made you, you think your brain is the mind, you think a creator made you, you think you began in your mother's womb, you think other people cause you happiness and suffering. He says we've basically got it all wrong. So, essentially, Buddhism is a way of interpreting the world. The reason you are a Buddhist, the reason why you'd study it, is so that you can reconfigure the way you see the world.

The Buddha says that once you're in sync with reality, the result is happiness, the result is bliss, the result is freedom from suffering. So how you think has got everything to do with happiness and suffering. That's why you study Buddhism.

All of this sounds quite scientific – it’s just about the mind. Would you say that people nowadays are attracted to Buddhism because it can be studied and practiced without the need to adhere to certain dogmas or theories?

You can be a 1% Buddhist, or you can be a 100% Buddhist. It's up to you, and what I find so empowering is this point. Why is that so? On the face of it, Buddhism looks like any other religion. You go to a Tibetan monastery, and it's dripping in holy things and rituals. But, actually, the fundamental difference to other religions is that the Buddha is not a creator. The Buddha doesn't assert a creator.

A couple of years ago, I heard His Holiness the Dalai Lama say, in passing, that it was these amazing Indians more than 3,000 years ago who were the ones who began this incredible investigation into the nature of self. They were the ones who created this extraordinary technique called single-pointed concentration that enables you to plumb the depths of your own mind. They actually mapped the mind. But what do we know in our culture about the Indians? Nothing. We know all about the Greeks and the Romans. The Buddha came out of this extraordinary Indian tradition, completely immersed in discovering his own mind, discovering reality.

Then he moved in his own direction, based on his own findings. So when I think of that, Buddhism is not a belief. It's not a belief system. The Buddha was a regular guy. So, if the Buddha was a regular guy who became a Buddha, then all the methodology is there for anyone to take, according to their own pace and liking. It's not a question of believing it, or a question of being 100% or 1% Buddhist. You do it at your own pace. It's basically being your own therapist, like Lama Yeshe puts it.

How does the Buddhist concept of karma intersect with the idea that our mind plays a pivotal role in our experiences of suffering and happiness?

What the Buddha says, his view, and this also comes from those amazing Indians who saw the same thing, is that sentient minds, consciousnesses, sentient beings, are mind-possessors. There are trillions of mind-possessors, humans are a tiny percentage. There are all the animals, other creatures, so many other sentient beings. These consciousnesses, these mind-streams, are not physical and are not the handiwork of a creator, nor are they handiwork of mommy and daddy. These are the usual options we have on this earth.

They have their own continuity, and these consciousnesses go back and back and back and back. That's the Buddha's observation; he didn't make it up, it wasn't revealed to him. Every millisecond of what goes on in those minds is what's called the law of karma. Whatever goes on in those minds will sow seeds in those minds or program those minds, which will produce the future experiences for those beings. So, as His Holiness the Dalai Lama said one time, "Karma is self-creation."

This takes a while for us to get our heads around, because we're so used to blaming mommy and daddy, blaming others, blaming external things. But the Buddha says, "We are the cause of all our happiness, and we are the cause of all our own suffering."

That's the basis of what practice is in Buddhism. Given that I'm sick of suffering and I do want happiness, guess what? I'm going to stop causing suffering, I'm going to try and cause happiness, because I realize I am in charge, I am the boss, I am the creator. This takes a while for our heads to get around, because it's such a different model.

But this is the Buddha's view, and he says it's a natural law. There's no punisher and there's no rewarder. It's not a moralistic statement at all, it's a natural law. The Buddha says we all create our own experiences, which is pretty intense because then we'll take responsibility, then we'll give up being angry, and resentful, and blaming, and being a victim. So, it's quite powerful.

You are well-known for your dynamic personality and sharp wit, and for working on a wide range of social projects such as the Liberation Prison Project, which has brought the Buddhist teachings to over 20,000 prisoners across the globe. Yet, in the West, there is often this idea that Buddhism is rather passive – that we just sit on cushions and close our eyes and detach from the world. What are your thoughts on this?

That's the most bizarre thing I've ever heard in my whole life! There's this lovely analogy in Buddhism that a bird needs two wings to fly – these wings are wisdom and compassion. The compassion wing is the action wing, that makes us get out there and be of use to others. But until I do something with myself, I can't even be helpful to an ant. That is the wisdom wing.

Probably what people think of as passive is the sitting down with your eyes closed looking holy, because that's the internal job. But that's the one we have to do first: I've got to know my own mind before I can help somebody else. It's not possible that I can help someone else if I don't know my mind. Being passive is the utter opposite.

Would you say that you need to approach teaching the Dharma to prisoners in a different way than, for instance, students that come to a Dharma center?

I think all humans are identical. What's fascinating about Buddhist psychology is that it refers to all the other beings as well, including animals. So, when you use the Buddha's model to know your own mind, you can understand a lion's mind, the dog's mind, the psychopath's mind, Mr. Trump's mind, because the model to know your mind is the same for all sentient beings as far as the Buddha's concerned.

We're all variations of the same theme. We've all got attachment, we've all got ego-grasping, we've all got anger, depression, low self-esteem, a bit of love, a bit of compassion. And luckily, as humans, we can access this. I think wherever you go, we're all the same. Whether I talk to people in prisons, I talk to intellectuals, I talk to scientists, I talk to children, there's no need to use any different language.

Some people might think that people in prisons deserve to be there. As in, they’ve committed crimes and belong in prison and, well, some of the worst criminals are not even worthy of forgiveness. How can we learn to forgive?

The usual view of religion is that there's a creator, that the world is made by a superior being, that I'm the product of a superior being, and therefore the superior being is the boss. I'm not being rude about that, there's nothing wrong with that, it's one view of the world.

My Jesuit priest friend, whom I have nice discussions with, I asked him, by definition, “What is a sin?” And he said, "By definition, a sin is doing what God said you shouldn't do. Going against the will of God." So, I think that's the view we have of doing “bad things.” In my mother's house when I was a little girl, and mommy says, "Don't do that," and when I say, "Why not?" we know her answer: "Because I say so." So, we have this dualistic view of good and bad.

There’s this idea that when you do a naughty thing, to be purified of it, you have to be forgiven by the person you harmed. But that's not the Buddha's view at all. So, people often ask where forgiveness is in Buddhism?

Well, the Buddhist view is based on compassion, which is based on the understanding of karma. The Buddha is saying that every sentient being comes into this world fully programmed with our own tendencies and our own experiences.

Everything we think or do or say brings consequences to ourselves. There's no punisher in Buddhism. There's no rewarder, there's no dualistic concept like that. Therefore, the process of changing yourself is that you first have to recognize that you're sick of suffering, and that's why you have to stop killing, lying, and stealing.

Then you have compassion for those you harmed, and you even have compassion for those who've harmed you, because you know they're going to suffer in the future. Then, of course, on the basis of compassion for them, that includes forgiveness. Of course it does, it would come naturally. So, it's a different kind of approach, on a different basis.

If you had one thing to convey to someone who does not know much about Buddhism what would it be?

The thing that I find amazing about the Buddha, this amazing human being coming out of an extraordinary tradition, delving deep into his own mind, is that he is saying that the final goal for humans, that he achieved, is to rid the mind of all the rubbish. Now this is an insane concept. If I go to a therapist and I ask for techniques to get rid of all ego, all fears, all anger, all attachment, all jealousy, I'd be considered mentally ill!

It's a shocking concept, utterly radical, but because it's framed in nice religious words, we don't hear it. But this is what Buddha's saying. So, for me this is immensely empowering that I'm not stuck with the irony of ego. The irony of ego is that we come into this life addicted to our misery, addicted to negativity, addicted to unhappiness. That's our trouble. But what I hear Buddha saying is that they're not at the core of my being. Anger, attachment, neuroses are not at the core of my being. The goodness is, the virtue is, the intelligence is. So, when we hear that, it can give courage, it can give inspiration, that we can change. We can change, and I have to do the changing.

Dear Venerable Robina, thank you so much for this powerful wisdom and the encouragement to take control of our own lives!