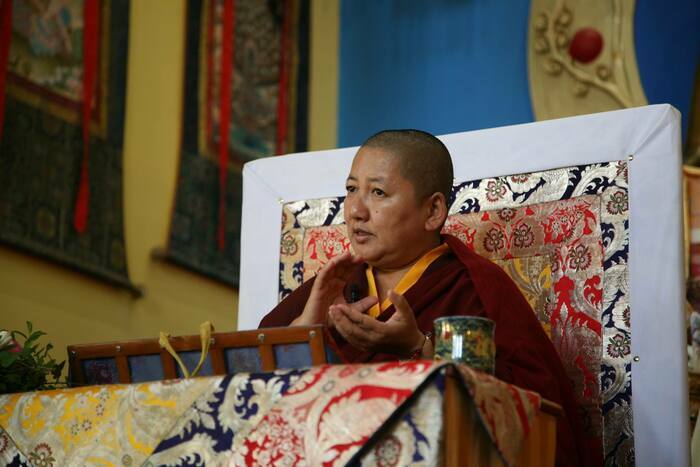

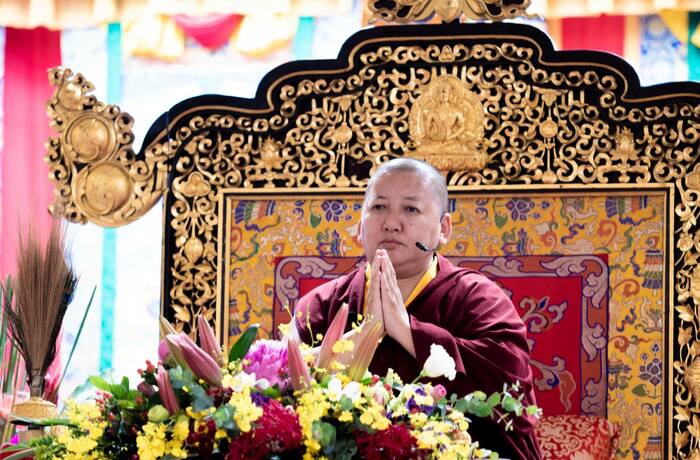

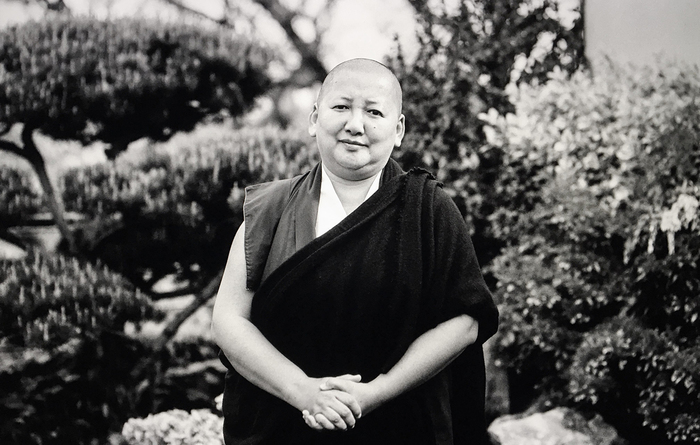

When I first became interested in Tibetan Buddhism, one of the first books that I read was This Precious Life: Tibetan Buddhist Teachings on the Path to Enlightenment, by a female Tibetan teacher that I had, at that point, never heard of. The powerful teachings within the book, expressed with such clarity and beauty, propelled me to want to learn more and more. And that is why I am so excited for today’s interview. We’re at Dharma Mati Buddhist center in the far west of Berlin, and we’re about to meet one of the highest female lamas of our age.

Her Eminence Mindrolling Jetsün Khandro Rinpoche is a holder of a unique lineage of female masters known as the Jetsünma line, and the daughter of the renowned Mindrolling Trichen Rinpoche, the throne holder of the illustrious Mindrolling lineage of the Nyingma tradition. At the age of two, she was recognized by His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa as the reincarnation of Khandro Orgyen Tsomo, a revered female master who spent much of her life in retreat.

As a holder of both the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages, she is actively involved with Mindrolling Monastery in India and the Samten Tse Retreat Centre in Mussoorie, India, which she established as a place of study and retreat for both nuns and Western lay practitioners. Khandro Rinpoche leads several charitable organizations in India as a legacy of the vision of her root guru and father Trichen Rinpoche, who felt it crucial for Buddhist practitioners to engage in actions benefiting others.

She is known for her direct, no-nonsense, and humorous teaching style. And here, in this interview, she doesn’t disappoint

Study Buddhism: Rinpoche, you have a lot of insight into the development of Buddhism in the West due to your extensive teaching tours around the world over the last few decades. Access to Dharma teachings seems to be growing exponentially, especially online. Is this very easy access to the Dharma necessarily a positive phenomenon?

Khandro Rinpoche: I started travelling in the late ‘80s, and looking back now, I am a little bit nostalgic about that period in time because when Buddhism appeared in the West, there was so much heartfelt inspiration. There were fewer Dharma centers, fewer teachers. I was very impressed by the caravan of people following the teachers visiting throughout the summer, having left their jobs and their families. At the Dharma centers there were no adequate accommodations – so the whole field around it used to be dotted with tents. In rain and snow, people would be very devoted and practice diligently.

In the last few years, in the last ten years especially, things have changed. Now we are very structured, there are enormous Dharma centers that are well-established, and provide very exhaustive, intensive programs and materials. While this is wonderful, I miss the simplicity of the old times, like being in a tent. I don't know how much of that is nostalgia.

People are studying and learning more. The Dharma has never been more accessible to the common people than it is today, or those who are not necessarily serious monks, nuns, and yogis, which I think is very good. Buddha's teachings have been able to come into being, merged with a sort of a community of people who are not the stereotypical religious people, which I think is wonderful.

At the same time, the Dharma being so accessible can have downsides. I don't know how many will be able to realize the preciousness of the Buddha’s teachings when we access it so easily. Of course, alongside with it, teachers and students will probably develop very skillful ways of communicating the preciousness of it.

What I see is that because teachings are so easily accessible, the tendency to treasure it and the kind of diligence it requires is waning. Also, I feel that the edges are still quite blunt. The real sharpness of wisdom that needs to come, that has the power of cutting through, is yet to be seen. What I do aspire and hope to see is that we don't get lost in the “corporate-ness” of it all.

Even if meditation and mindfulness have become widespread and well-known, I find that a lot of people – even those studying Buddhism – barely know what meditation is or what the point of meditation is. As a teacher, what kinds of misunderstandings about meditation do you commonly encounter?

Someone wanted to know more about meditation, so I asked them, "Do you meditate?" And he said, "No, no, no, no! I don't meditate. I can't sit still for so many hours." So that made me think about how people in today's world interpret what meditation is.

They think meditation is confined to sitting in an awkward posture for hours and hours. Well, that is one way! That's one of the poster postures of what meditation is. But meditation is about gentle observance and watchfulness. That's what I always emphasize. That prior to even thinking that you are a meditator, you have to exercise the natural human ability of being watchful and observant about simple things: how you're talking, how you're eating, how you’re thinking. For example, it is so drilled into us that when we meet someone we say, “How nice to see you!” Whereas the mind might be thinking something entirely opposite!

Meditation would be that you observe such a thing, and you question yourself, "Now, why did I do that?" Not that you would just go and say, "I was trying to avoid you," but observe why you could not make that expression an honest one. So, another aspect of meditation would be that as a human being, you could work with your own self to be more honest in any given moment.

Because you are the creator of your own experiences, it is you who create an experience that you are constantly pursuing, an experience of happiness or an experience of well-being or friendship or whatever is it. That's an important aspect of meditation that people need to understand. Of course, traditional forms of training the body, speech, and mind may also be helpful in this kind of a recognition and to make it fertile, productive and constructive.

As you say, we are the creators of our experiences: we can create suffering for ourselves just through the power, or rather confusion, of our own minds. I have a friend who on Fridays always screams, “I’ve had a week from hell!” What is the Buddhist understanding of hell?

I joke with my friends who have become Buddhist from a Christian background that they had to deal with one hell then, which was too much for them, and now they come to Buddhism, where we have eighteen hell realms. A "from the frying pan into the fire" kind of situation happens!

When you have a very narrow and limited understanding about the capacity of the mind's potential for conceptualization, you create a very small world around yourself, within which certain things are possible and certain things are not possible. In this case, don’t struggle to understand the Buddhist concept of hell realms. If you don't believe it, you don't believe it. That is one way to look at it.

Instead, try to understand the creative potential of your mind. Then make it bigger, come out of your own little world to begin to actually see the limitless potential of creation that your mind has.

For example, when you smile at a person you pass by and the person doesn't smile back at you, your mind can go into a whole storyline. How good or bad you are or the other person is, immigration problems, cultural differences. You can write a whole thesis on it!

That's how creative your mind is. If you look at that creative potential of your mind, then you begin to understand that it can create worlds of experiences of its own.

Hell, and the whole concept of hell is just such a miniscule example of the torture and the enormous suffering that our mind can actually create. If you interpret it that way, it's not hard to explain. Eighteen hell realms is just the top of the crust, as they say. They are just part of the limitless creation of diverse hells here and anywhere else.

Therefore, training our minds is the key to how we experience life?

Yes. Hopelessness is when you're entirely dependent upon everything and everyone else to obtain what you wish to experience. Mind training allows an individual to not be stuck in that state of hopelessness.

You're not dependent upon another person, but you really exercise your own ability and freedom. When you go from being entirely dependent to being free, to creating and molding your own existence, you bring to fruition your own expectations and aspirations.

True freedom comes when you understand your own inner abilities, you hone it and you let it really become the basis of your own existence.

I guess that sometimes it’s difficult to grasp how to exercise our own abilities and freedoms, and to realize just how precious it is to be born as a human. I think that a lot of us go through our days feeling quite “meh” about everything. How can we fight this feeling?

Life is precious, because it is in this human form that your senses, your experiences, your emotions, and your feelings are all rooted into your own mental awareness. That's an exceptional gift. The ability of making things happen, making this moment really happy and joyful and constructive is a potential that we all have as a human being. Non only do you have this potential, you also have the extra advantage of having the intelligence that recognizes it.

That makes it the most precious of all existence. Traditionally, I could count the eighteen qualities, but all of them come into that one single thing. It's that all causes and conditions equip you to be able to be the creator, the director, the painter, the sculptor of a moment. Who enjoys such a freedom and ability other than a human being? That's what makes human existence so precious.

Nowadays, social media is an integral part of life, especially for the younger generations. On the various social media platforms, we are constantly inundated with different information, views, and more recently, “truths.” How can young people learn to navigate this often-treacherous experience?

I would like to encourage young people to speak to each other, to be involved in the exchange of ideas and to question their experiences in life. These exchanges can never be constructive if you're limited in your own mind by thinking that somebody else has to create an environment where those questions can be addressed. To think that everything can be just typed into Google and then it'll pop up and you'll find a solution: it's not going to happen. Discovery requires you to get up and go.

Young people today need to really understand the importance of not relying upon leaders to show them the questions or the answers but must have the courage to really spearhead dialogue and research. You have to be leaders in your own self to be able to have the courage to question, to search for the answers.

Another issue we face nowadays is that with such easy access to information, we can see so clearly the social inequality, warmongering fear, and environmental destruction wrought upon the planet by what often seems like a handful of individuals. How can we develop compassion for those who cause such pain and suffering in the world?

It is not easy to have compassion without bias, if it doesn't begin a little bit earlier in your mind-stream. You have to work with the causal factors, and that's beautifully explained in the Mahayana teachings.

We really need to understand that we are the recipient of a lot of kindness from others, from our interrelationship with others, and understand that the concept in Buddhist teachings of “mother-like sentient beings” is not just poetic. The birth of any attitude of kindness and compassion is always born from a recognition of how much we are at the receiving end of others' kindness and compassion, whether of our actual mother or anyone else.

Even when we drink a cup of tea, we need to understand the larger picture of how many contributing individuals have gone into making that moment possible. When we ignore that fact, we begin to develop a very individualistic, hardened, island kind of a mind of our own.

That's what makes compassion and the practice of compassion difficult. It's because we think we are an individual, unattached and not in any way related or connected to others.

But when the connectedness and the interdependency of ourselves with everyone else is understood, we come to a point in our mind where we realize that we are receiving so much. We can say thank you and think about how best to repay all that we received. Without that kind of an understanding, then the patronizing attitude of, "I'm the good one who's always giving compassion, not getting anything in return" can easily come.

Would we call what you just talked about “ordinary compassion?” Buddhism talks about immeasurable compassion too. What is the difference?

Immeasurable compassion, from the perspective of it being an immeasurable quality, can't be confined to one word. For this reason, within the context of the immeasurable teachings, we have immeasurable love, immeasurable kindness, immeasurable joy, and immeasurable equanimity. It has to suffuse the essence of all these four, and even many more different qualities for it to be truly immeasurable compassion. The basis of everything that you would do, say, and think would be infused with a lot of thoughtfulness about others. If you say something, the underlying fragrance of that moment would be, “Would it be good to somebody else?”

I wanted to go back to misunderstandings about Buddhist topics. I think a lot of people who don’t know much about Buddhism think that it’s all quite nice and lovely and light-hearted, a kind of “do whatever you like” philosophy. And then beginners, when they actually look at the Buddha’s teachings, are taken aback and maybe even discouraged: it’s all suffering, impermanence, and death! What would you say to such people?

It's almost as if someone started a rumor saying that impermanence is bad news, and since then we’ve become convinced that Buddhism is just about impermanence and suffering, terribly gloomy subjects. Still, all the Buddhist teachers keep telling us that “impermanence is good.”

I think we need to think differently. We need to think of impermanence as:

"Therefore, this will also pass." Therefore, this suffering will also pass. Therefore, because there is death, there is rebirth, there is birth. Because this changes, something new can happen.

That’s probably why we celebrate the new year. It is about a new beginning, a freshness to a day. But we take that as a pretext to celebrate the potential of having another chance, and that is good news.

I think the whole idea of contemplating death and impermanence is to treasure the present moment. Thinking about impermanence and death is an important aspect of Buddhist contemplation. I love Milarepa’s story, where he says, "It is death and impermanence, and what happens at the time of death, after death, that inspired me to go into the mountains and meditate, until a time when I am no longer afraid of death anymore."

This is so beautiful. It has to be understood properly. The whole Buddhist view of contemplation on impermanence is that it allows you to see change, that everything is transient in nature, it's interchangeable, it's exhaustible.

I think human beings would have a greater ability to relax and have more humor in their lives if they understood this perspective of change and the transient nature of the self and everything else.

So, there's a little bit of sunshine or brightness in the contemplation of impermanence and death that has to be understood as well. Otherwise, if you look at it only from the point of view of making you feel bad and poorly and miserable, then that loses the whole purpose of the topic of contemplation on impermanence and death. There is really no benefit if your contemplation debilitates you.

As a Tibetan woman, you are rather unique as a teacher – over the last few decades, we can pretty much count on one hand the number of female Tibetan lamas that have taught in the West. As in the majority of religions and cultures around the globe, women have faced prejudice in Buddhist societies. How did you overcome any such prejudice?

Up until about the last two decades we've seen very few prominent women teachers.

I think it's due to a lack of education. Societies in the East, in India and in Tibet, and basically wherever Buddhism grew, were very patriarchal. A patriarchal society limits opportunities for women to study and be independent.

But you have to study, you have to be independent to manifest any kind of realization or understanding. You'll be wrong to imagine that bodhisattvas just drop down from the skies and automatically arise as women and men or whatever. A lot of hard work is involved in the sense of learning, practicing, and being in retreat. Being independent to experience and accomplish. Women often didn't get that opportunity, so there were limited numbers.

Fortunately, that seems to be changing. I really think opportunities for education have now really increased for women, and they're becoming very competitive and learned.

While there are textual sources which don't make any disparaging remarks or have any kind of a biased outlook towards women, it is actually quite the reverse within the mahamudra and the dzogchen traditions. But you need to view them as literary works of scholars and masters who have their own opinions because they were brought up in that kind of society.

There's a lot of, "May I not be born as a woman." It's a very common statement in some Buddhist prayers, which really shocks people who come to Buddhism thinking it's all about one truth and unbiased compassion, selflessness, and egolessness. And then they find such discrimination. Women find it very jarring, very disrespectful and discouraging. But you have to understand that these are literary works and interpretations of an individual's perspective.

I never allowed that to be any kind of a blockage. I have gone to my teachers, especially my father, complaining about it saying, "Look, this is what you all have been writing about women, and how is this not contradictory to just the other day's teachings that you have been giving?"

And Rinpoche would say that ultimately Dharma is view, and you have to examine it, think about it, you have to mull it over in your own mind, experience it, and then make a decision based upon your own understanding, rather than what somebody is trying to tell you. This advice has been tremendously helpful for me. These days I take it in a relaxed attitude or with some humor, and see it as an individual's interpretation, rather than necessarily the Buddha's words.

When His Holiness the Dalai Lama says he could reincarnate as a woman, it is a great message for women and for men who might have that question. It is the immeasurable kindness of His Holiness and his realization through which he is able to proclaim this.

On the other hand, we have to be very pragmatic about it. The institution of the Dalai Lama and who he is and manifests as, must never be limited to being an answer to only one question. The Dalai Lama has limitless responsibilities and activities that must reach out to the greater goodness. And if that greater goodness can be achieved by his coming back as a woman, wonderful. If, however, it is not timely, we can wait.

It's great to hear that times are changing and progress is being made. In a previous interview with Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, we talked about how nuns often do much better than monks in the exams, now that they have been given access to a full education. So, it really is all about education, as you say. Actually, under Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, nuns in Northern India have recently resurrected the dakini dance, a ritual dance practice that dates back to the beginnings of Vajrayana when it was performed by both female and male monastics. The word “dakini” is thrown around a lot – what does it mean?

I don't think many people understand what a dakini is. I hear all the time: “You're a dakini,” or, “A beautiful girl is a dakini,” or, “A wonderful strong woman is a dakini,” or, “Someone you respect and really see as an inspiration is a dakini.” Contrary to what people think, the concept of “dakini” is not limited to women or being feminine. Dakas and dakinis are synonymous. Anyone that has cut through the illusory deception is a dakini. It's not restricted to women and should never be used as a compliment that people make to women.

Also, perhaps people think a dakini is always very beautiful and gentle and kind and mother-like and nourishing and a strong woman and so forth. I don’t think these people have necessarily met one!

To finish up, could you tell us what you think the essence of Buddhism is?

The essence of the Buddhist teachings is all about encouraging an individual to be more insightful and introspective. To broaden one's mind to an understanding that requires a lot of delving into one's own self, one's own mind, one's own thinking patterns.

Unfortunately, resistance through our habitual stubbornness and habitual patterns is there. According to the Buddhist teachings, the opposite of wisdom is ignorance. So, you have a constant struggle between your innate wisdom that does have its own natural potential to be introspective and insightful, yet it hits the resistance of habitual ignorance.

Therefore, all the learning emphasized in the Buddhist teachings is about working through the excuses. The aim is not to acquire wisdom but to develop a powerful antidote to the excuses and the tremendous habit of stubbornness that just doesn't take things simply and as they are.

Therefore, it becomes necessary to study. It depends how stubborn you are, and how sneakily you can continue to defend yourself against what the truth is. As long as that streak in you continues, you have to study. Therefore, there is no end to studying!

Rinpoche, thank you so much for your unique insight into the world and the Buddhist teachings!