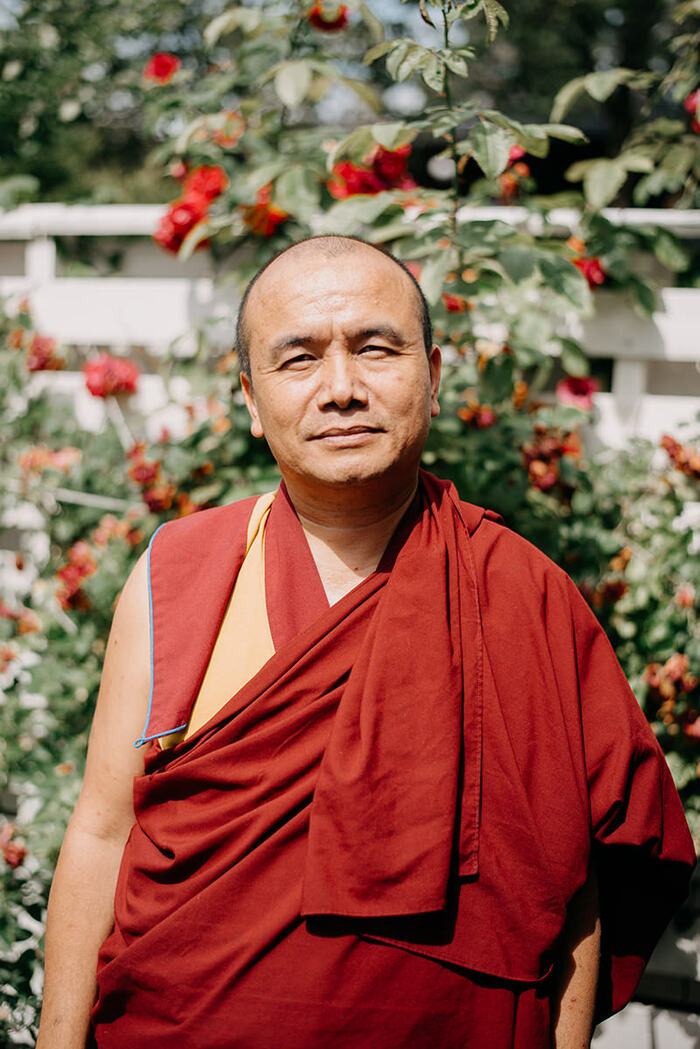

Amidst the serene beauty of a countryside garden in Oulunkylä, Helsinki, Finland, I had the honor of engaging in a profound conversation with Geshe Dorji Damdul, a distinguished Buddhist scholar and teacher with a passion for science. The setting seemed almost symbolic – a tranquil environment echoing the peace and wisdom we were about to discuss. A scholar of Tibetan Buddhism and an expert in both Buddhist philosophy and contemporary science, Geshe Damdul serves as the Director of Tibet House in New Delhi, India, a cultural institution dedicated to preserving and disseminating Tibetan culture and religion.

During the interview, our dialogue traverses the fascinating landscape where Buddhism and science converge and diverge. Geshe Damdul's insights into the parallels and intersections between these two realms are truly enlightening, and he eloquently articulates how both disciplines seek to understand reality and explore the nature of existence, albeit through different lenses. His nuanced perspective illuminates how, rather than being in conflict, Buddhism and science can mutually enrich one another, fostering a deeper understanding of both the external world and the inner dimensions of human consciousness.

Among the intriguing subjects we explore is the brain-mind paradox – a topic that is increasingly drawing attention from both neuroscientists and spiritual practitioners. His reflections on how understanding the intricate interplay between the brain and the mind can reshape our understanding of the self and offer new insights into the profound mysteries of our existence.

Yet another compelling topic we touch upon was the urgent need to introduce universal ethics into modern education systems. Geshe Damdul passionately articulates how infusing ethics based on compassion, empathy, and mindfulness into education could pave the way for a happier, more harmonious world. His vision of nurturing not just intellectual growth, but also emotional intelligence and moral values, resonates as a powerful antidote to the challenges facing contemporary societies.

As we immersed ourselves in Geshe Damdul's wisdom, the garden seemed to take on a deeper significance, echoing the interconnectedness that he so eloquently conveyed between the teachings of Buddhism, the progress of science, the mysteries of the mind, and the pursuit of universal ethics. It was a privilege to engage with this erudite scholar and compassionate teacher, and the echoes of our conversation continue to resonate as an invitation to explore the boundless potentials of knowledge, understanding, and harmony in our lives and in the world. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: Since childhood, you’ve had an enduring fascination with science. Could you elaborate on the parallels and distinctions between contemporary scientific pursuits and Buddhist philosophy in their shared quest to understand reality?

Geshe Dorji Damdul: Both modern science and Buddhist philosophy are looking for objective reality; they are looking for the truth, independent of what you think, independent of what you’ve learned. What is really out there, what is reality. This is something in common between these two disciplines. The next point of similarity between the two disciplines is that both of them search for reality not through dictates or dogmas, nor through mimicking earlier teachers or saints, but rather through reasoning. This is something that is a great commonality between Buddhist philosophy and modern science.

What, then, are the points of divergence between these two disciplines of modern science and Buddhist philosophy? In the Buddhist concept of reality, all phenomena can be classified into three groups: evident phenomena, slightly hidden phenomena, and very hidden phenomena. The Buddha explains all three types of phenomena, whereas modern physics is confined to evident phenomena and some of the slightly hidden phenomena only. Modern science doesn’t touch upon concepts that the Buddha talked about – most of the slightly hidden phenomena and all of the very hidden phenomena.

My personal take is that modern science is an extremely rigorous system, and it is one of the treasures of the world today. However, we shouldn't be naive, because even though science is a greatly rigorous system, that doesn't mean that it can explain every single phenomenon. Because in reality, science is confined to manifest phenomena and only some slightly hidden phenomena.

Another point that we need to keep in mind is that modern science develops. Let's take modern physics as an example. Earlier, we had Newtonian classical physics. Then, after about 200 years, with the advent of quantum physics and relativity theory, there was a sudden jump, a paradigm shift, from Newtonian physics to quantum physics. The concepts and the basic understanding of these two are very different. We have the foundation of Newtonian physics, on which so many developments came about. But what was once considered as the truth, later on, with quantum physics, is proved to be wrong. There's a paradigm shift happening. Likewise, at the moment, neuroscience cannot explain rebirth or the laws of karma and so forth, but in the near future, we never know the advancement and developments that might happen.

Neuroscience in particular is developing so fast. We don't know where neuroscience will go. It may come to an understanding of the existence of a mind different from the brain. This is very possible, but for the time being, neuroscience is yet to reach that level of sophistication to be able to study this area.

In which particular areas do you perceive the potential for Buddhism and modern science to mutually complement and enhance each other?

His Holiness the Dalai Lama makes it very clear that modern physics, and for example its explanation of elementary particles, is extremely precise. The measurement of electrons, mass, the velocity at which it all moves are so well-defined in modern physics. Of course, the Buddhist study of particles talks about the subtlest or ultimate particle, and whether such a thing exists. But the way that physics explains particles in such minute details is not found in the Buddhist concepts in the Abhidharma. These are things that we can really learn from physics.

In terms of the concept of dependent origination, for example, physics has the relativity theory and quantum physics. Today, physics broadly covers these two areas. So how can we bring the two together? Well, physicists don't really have the answers yet. Albert Einstein was working on the Grand Unified Field Theory. In Buddhism, in the Heart Sutra, Buddha very beautifully taught that the same object can be seen from two different points of view. We cannot describe the same object seen from the point of view of the first reference, keeping in mind the second frame of reference, because the frames of reference are different.

Like quantum physics states, the same particle can behave as a particle or as a wave. So, we cannot use the same frame of reference to look at the same particle to see that it's behaving in two ways. If you design your experiment in one way, then the particle can behave as a particle. But if you design the same experiment in another way, the particle can behave as a wave.

This is what the Buddha stated very clearly with the two truths. This understanding of the two truths in Buddhism can really help scientists and physicists to understand the broader picture of the various theories of physics and put them into perspective.

Now, looking at neuroscience, Buddhist psychology can be of benefit. Neuroscience, at the moment, is developing at such a great pace, but it needs direction. Neuroscience is looking at the brain, how the mind functions, and how the brain correlates with mental functions. The mental functions are important in Buddhism psychology, and there's a tremendous explanation of how the mind works. All these explanations can help neuroscientists to learn and, on that basis, they can look for the nuances themselves.

Many people see parallels between the propositions of quantum physics and Buddhist philosophy, particularly the tenets of the Chittamatra Mind-Only School. From your perspective, do you see any significant resemblances between these two?

The main similarity is the relationship between subject and object. When you look at a flower, it gives you a very pleasant feeling. However, the same flower seen at the level of chromosomes is very scary to look at. It's like a brown, scaly-looking structure, almost snake-like, and it's very repulsive to look at. And then you go deeper, and you see the atomic level. When you see the same flower at an atomic level, you can see it as electrons, protons, neutrons and so forth, the pleasant feeling disappears. It's not repulsive, it's not attractive, it's neutral. It's the same object, whether you see it as a whole flower or as individual atoms.

The exact same object can trigger three very different emotional states. The question, then, is, "What is really there from the side of the object?" If we say that all three emotions are correct, how can three things that oppose each other be the reality of the same object? The answer is that there are three different perceptions taking place. Perception is purely subjective, coming from the subject, not from the object. So, in Chittamatra philosophy, the flower existing on its own as something external out there is not true. It's just a perception of a flower and that occurs solely within the subject. The observed object is completely dependent upon the observer. This is the Chittamatra point of view.

In quantum physics, if there is an electron there objectively, we should be able to discern the momentum and mass precisely. But according to quantum physics, the observed object makes no sense independent of the observer. In short, as for the momentum and mass of the electron, we cannot really precisely discern these within any given time. If you speak about mass, you need to reconcile the momentum. If you speak about momentum, you need to reconcile the mass.

The way the object behaves is in dependence of the observer. The object is heavily dependent upon the observer. What does that mean? Well, physicists come up with different views. Some would say that, yes, the object is dependent upon the observer; the observer is like the mirror, and the observed object is like the reflection.

We need to understand both quantum physics and Chittamatra philosophy well. Quantum physics says that independent of the observer (subject), the observed (object) makes no sense. Chittamatra philosophy would say that independent of the mind, the object makes no sense. So, there is a very close semblance there, but we can't say that they're identical.

You have had a life-long interest in exploring the enigma of the mind-brain relationship. Are the brain and mind the same, totally different, or interdependent? Could you also shed light on the concept of the brain-mind paradox and its implications for our understanding of the self?

When I joined the monastery, I started this journey of seeking to understand whether or not there's a mind that is different from the brain. This is a very interesting journey of almost over 30 years now, exploring whether there's a mind different from the brain.

The brain and mind paradox is a very complicated issue. We can talk about the two current hypotheses of neuroscience. The first hypothesis is that there's no mind, there is only the brain. The second hypothesis says, yes, there is mind, but it is an emergent property or derivative of the brain. When the brain dies, the mind disappears.

First, we need to know the basics: what is brain, what is mind? To explain it in very simple terms, you can imagine going back in time and imagine that your mother is cuddling you when you were aged three or four, so vulnerable and dependent on others, and your mother is looking at you with so much love and affection. While you are imagining that, neuroscientists put you in the fMRI scanner. While you are thinking back to this memory, the neuroscientists can see your brain waves and the neural firings, where the neurotransmitters are transmitted from one neuron to the other, what kind of synaptic conditions are there, and so on.

The neuroscientist can see all of that so well, but they can't see what you're thinking. So, the point here is the distinction between the brain and the mind. You are the only one in this world who has this experience of what you are thinking. The neuroscientists have no clue. What you're thinking, which you have the direct experience of, which neuroscientists have no clue about, that is your mind. The brain waves, the synaptic connections, and the neurotransmitters being transmitted from one neuron to the other which neuroscientists can see, but which you cannot see, is your brain. This is a distinction. Next is the paradox.

The paradox is whether the mind exists as different from the brain, or as some derivative or emergent property of the brain. This is a very serious question. Many people have already heard about neuroplasticity. Earlier, the belief amongst neuroscientists was that the brain affects the mind, and that it works only one way – the brain affects the mind, but the mind does not affect the brain. Now with the advent of more sophisticated neuroscience, we see that not only does the brain affect the mind, but the mind also affects the brain.

Actually, I'm planning to write a whole book on this, the paradox concerning the brain and mind. I'm continuously learning and reflecting on the points and updates from neuroscience, and then thinking more about the great Indian Buddhist philosopher and logician, Acharya Dharmakirti's text, Pramanavarttika, Chapter Two. I'm trying to study both sides, coming up with my own reflections.

One of these reflections is about the sense of identity, the "I." I identify myself as a male, and girls will identify themselves as girls. Males, females. I'm Dorji, I'm Tibetan, and so forth. This is how we identify, and this identification becomes the center of the universe, the center of the world, and on this basis we operate: I need a job, I need to survive. I belong to this country. I want to travel. I need this.

What is this self? From childhood until now, I have had this sense of self. At the same time, this self is determined by the mind. This is the mind I was talking about, which the scientists cannot see, but which you can empirically experience. On this basis, with elements from the body, we see a self.

In terms of the body, at the time of conception in the mother's womb, we were just one cell. Now we have trillions of cells. Where did all these cells come from? From the food that we ate. The majority of the cells that constituted your body when you were a very young child have been replaced. The only cells left are some long-lasting cells, such as neurons. That's 3% to 5% of the body. Otherwise, you have a totally new body, but the sense of self is the same. If we have a totally new body, and the self is designated on the basis of the body, then there should be a new sense of self.

But it's not the case. So, the sense of self is not created by the body. It's created by something that we empirically experience as the mind. Yet this mind requires a support: the body and in particular the brain. With this support, the mind will remain within you until your body dies. And then as to how the mind gets transmitted to the next life, this is so beautifully explained by Acharya Dharmakirti in his book, Pramanavarttika, Chapter Two.

Compared to a hundred years ago, a very large percentage of people have access to modern education, which is seen as a gateway to equality, success and happiness. Yet, there has also been an exponential increase in the number of young people with mental health issues. What exactly is the problem?

When I was accompanying His Holiness the Dalai Lama as part of his entourage, we went to many places, and one question came up often from experts, whether medical experts, social workers, educationists or policy makers. The question was where are we going wrong? While modern education is meant to give rise to prosperity, harmony, and greater happiness, it seems that peace and happiness for humanity is going down.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama always says that it's because there are limitations to the modern education system. The modern education system is a legacy from the days of the Industrial Revolution, at which time the emphasis was primarily on material development and developing industry.

For material development, you need to have a good brain. You don't need a good heart! If a child is able to say 2 + 2 = 4, they pass. Whereas if a child has the capacity to become the second Martin Luther King Jr. or Mahatma Gandhi or Mother Teresa, and they say 2 + 2 = 4ish, they fail! Your heart won't be counted!

At the same time, His Holiness the Dalai Lama says we shouldn't turn the modern education system upside down, but it has to be supplemented with a curriculum and programs to develop the heart as well. We human beings have a brain and a mind, a body and a mind. For the body, we need material progress. For the mind, we need food for the mind, a good heart. So, His Holiness the Dalai Lama strongly emphasizes the need to incorporate programs for "universal ethics" into the education system. He says that the world is suffering due to this lack in universal ethics in the modern education system. He launched a beautiful program with the support of Emory University in the USA known as SEE Learning. SEE Learning means social, emotional, and ethical learning. They offer training to institutions wanting to introduce universal ethics into the modern education system.

Apart from adding universal ethics into the education system, what other suggestions do you have for students to create a more fulfilling and happy life?

People now are so engrossed with their own gadgets that they don't talk to each other; they don't look in each other's eyes. How can we rectify this very serious problem?

I would say that just as His Holiness the Dalai Lama introduced universal ethics into the modern education system, it would be good to encourage youngsters not only to stop using their gadgets at certain times and in certain places, but to let them see the drawbacks, limitations and side effects of using them.

I've visited an Indian girls' school in Dehradun, northern India, called Hopetown Girls' School. I was so inspired to see that the school encourages the students to take charge of the whole school for one morning. The students themselves design the program for the morning, and are encouraged to look at the demerits, weaknesses, drawbacks, and side effects of excessively engaging in gadgets, and how to protect oneself from the gadgets. It was a wonderful program.

And then, we could all have a day without gadgets. Just like we have World Health Day, World Parents Day, Teachers’ Day and so on, we can also observe a day without gadgets.

Talking of gadgets, most of us are constantly bombarded with bad news. We open our phones and bam! Environmental destruction, wars, political turmoil, famine, and so on. Sometimes it feels difficult to know where to direct our compassion, or sometimes we might feel some sort of numbness, or compassion fatigue. What’s the solution?

Well, this is really a question about sustainable compassion. You’re right, because sometimes it feels that the more compassionate you are, the more you engage in helping others, then the more likely it is to end up in burnout. We think, “Who's going to take care of me if I take care of others?” In Buddhism, we call it “skillful compassion.”

With skillful compassion, one should be very realistic, and also very practical and rational.

This is something to encourage to others, to youngsters and to elders and to everybody.

When we think that we're doing something for others, compared to when we think we're doing it for ourselves, burnout will happen much more quickly. Whereas, if we are able to see that, in helping others, we're actually doing it for ourselves, there will be very few burnout cases! This is simple human psyche. In a way, it's a human weakness. When you think, "I'm working for myself," you don't experience burnout so easily. When you feel, "I'm working for others," then burnout happens so quickly! Therefore, the basic underlying principle that we need to decode is that, actually, being loving toward others is ultimately a source of happiness for ourselves.

And being overly selfish – this is a source of misery. This is the principle that people need to have conviction in. When you develop that conviction, then the moment you're working for others, it will feel like you're working for yourself. When you feel that you're working for yourself, you don't feel burnt out. So, this is the basic principle. This is the key, which, if introduced to the world as a part of the modern education system, without a doubt will make the world a very happy place!

Dear Geshe Dorji Damdul, thank you for your incredible insight into the worlds of contemporary science and its parallels with ancient Buddhist teachings!