The train from Moscow to St. Petersburg winds through countryside lush with birch and pine, and, on this especially warm summer day, the sun-soaked landscape feels worlds away from the beautifully ornate palaces of the city itself. And on this trip, I’m not even here to visit the museums or estates. Rather, Dr. Andrey Terentyev, a pivotal figure in Russian Buddhism, has welcomed me to his dacha, nestled in the tranquil expanse of the Russian countryside.

At his country home, amid the scent of forest air and fresh dill from the local delicacies he’d set out, we settled into an afternoon of conversation. For decades, Terentyev has been a quiet but influential force in reviving Buddhism in his homeland. A lifelong scholar, he was drawn to Buddhism as a young man during the 1970s, an era when practicing any religion risked severe punishment in the Soviet Union. This passion led him on a clandestine path, one that included meeting Tibetan and Buryat lamas in secret, poring over smuggled texts, and ultimately inviting to the USSR the first Western Buddhist teacher, Dr. Alexander Berzin, to give underground teachings. Since the Soviet Union's collapse, Terentyev’s work and research as the founder of Narthang Publications has been crucial in helping to bring Buddhism to a wider audience in Russia than was ever thought possible.

During our conversation, we spoke about the harrowing years when Buddhism was driven underground and the unique Buddhist identities it took that evolved in Kalmykia, Buryatia, and Tuva, the regions of Russia traditionally influenced by Tibetan Buddhism. We also discussed the rich history of Buddhist texts and Tibetan medicine in Russia, a legacy nearly obliterated during Stalin’s purges but now experiencing a revival alongside a vibrant mix of other Buddhist schools. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: You embarked on your journey into Buddhism during your university years in the 1970s, a time when practicing Buddhism was strictly forbidden in the Soviet Union. What drew you to Buddhism under such challenging circumstances, and could you share more about both the barriers and encounters that shaped this period in your life?

Dr. Andrey Terentyev: I started university in St Petersburg in 1970 with the hope of studying Indian religions and philosophy. While we had a very good course on the history of philosophy, there was only one lecture on Indian philosophy! It was during this time that the Buryat Buddhist teacher Lama Bidia Dandaron, who wanted to revive Buddhism, was arrested and tried for organizing a Buddhist community. During the Soviet period, not only were almost all of the lamas arrested, but it was also forbidden to even just teach the Dharma. So, when I was at university, it was practically impossible to meet Buddhist teachers from outside the Soviet Union. They could only come as scholars.

Through the Asian Buddhist Conference for Peace organized by the Central Buddhist Board of Russia, some Buddhist teachers from Sri Lanka, India, and some other countries visited. Some Tibetan lamas also came, because the Soviet government was friendly with Tibetan refugees at that time, being opposed to Chinese communism. These were the only rare chances to meet Buddhist teachers from the outside.

I was fortunate at that time to meet Dagyab Rinpoche, and the older brother of the Dalai Lama, Taktser Rinpoche Thubten Norbu, who was also a scholar. While there was absolutely no chance of having official Buddhist teachings, some small personal teachings or clarifications on the Dharma could be received from these travelling scholars.

In an environment without access to teachers, Dharma courses, or even books, how did you manage to pursue a meaningful study of Buddhism? How did you overcome the limitations of such scarce resources?

In the 1960s, interest in Buddhism was awakening among a larger audience in the non-traditionally Buddhist areas of Russia among Russians in the Soviet Union. Most European Russians who became attracted to Buddhism and started to practice were mainly interested in tantric or Vajrayana Buddhism, because that was said to be the most advanced form of Buddhism.

We didn't have textbooks; we didn't have any texts at all! We had to study foreign languages, including Asian languages, in order to gain access to Buddhist teachings, so it was difficult. We Europeans are usually kind of extremists – whatever we do, we want to do it fast! In sutra-based Buddhism there is so much studying to do, but in tantra, you just do meditation, and you repeat mantras, and it is said to have a good effect.

The main problem with following tantric Buddhism was getting initiations, because that was nearly impossible. At the time, we didn't even know that Buddhist teachings actually existed somewhere else in the Soviet Union. In our university courses we spoke about Buddhism as though it existed a long time ago in some exotic countries. However, when people found out that there was some kind of continuation going on, that in Buryatia you could actually go to a Buddhist monastery, some people did manage to do so.

Some found Buddhist teachers – secretly of course – and started to study. These cases were very few, perhaps just a handful of people in Moscow and a handful of people in St. Petersburg. Any interest in Buddhism could not be officially shown by anyone, unless you were working in the lowest job and literally couldn't get any lower. That is why many Buddhist practitioners chose to work as street cleaners, or fixing boilers and central heating and so on, to avoid any possibility of demotion.

In the 1970s, what risks did people like yourself face for practicing Buddhism, and what kinds of consequences were imposed on those who were discovered?

When people tried to use what was called in the constitution the "freedom of faith,"

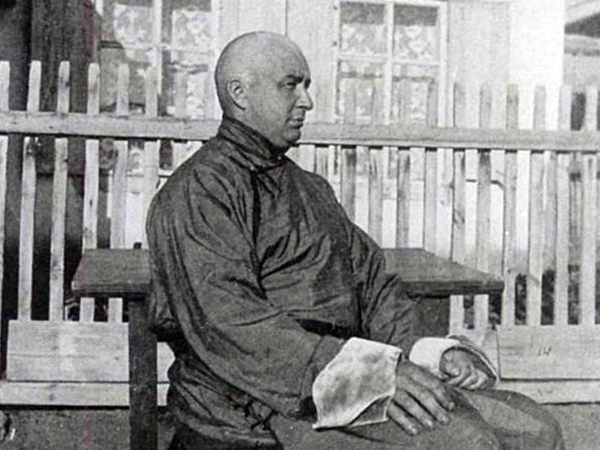

or the "freedom of conscience," the consequences were severe. Many people knew about the case of the Buryat lama, Dandaron. In 1974, Dandaron was teaching a group of Buddhologists. They were mainly Russians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians and Buryats. But when this group became recognized, all of them were arrested. Dandaron himself received a four-year prison sentence, and his main disciples were all placed in psychiatric institutions.

Therefore, people were very afraid of being persecuted for anything like this. I myself was also afraid, of course. I was working in the Museum of the History of Religion and Atheism which was the central place for state atheism in St. Petersburg, and maybe in the whole of Russia.

So, of course I had to keep my Buddhist practices a secret. I remember once at some work meeting, I was standing with my rosary in my pocket, but my pocket was torn, and my rosary slipped out! One lady, who was the secretary of a party organization, picked up the rosary. I was really afraid that my career was finished, but she was a nice lady, and she didn't tell anybody!

What was the earlier historical legacy and then the contemporary reality of accessing Buddhist texts and translations in Russia at that time?

The Buddhist tradition of translation in Russia actually started quite early on.

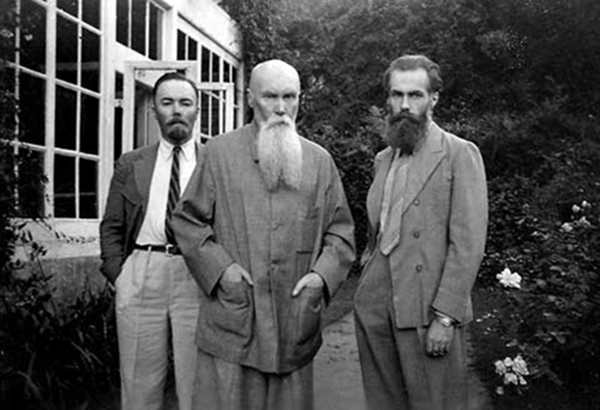

Starting in the 18th and 19th centuries, there were already pioneering works by writers such as Vasiliev, Schmidt and others. One of the first big Tibetan dictionaries was composed here, as was one of the first Sanskrit dictionaries. At the end of the 19th century, among the leading scholars of the Russian Orientalist Society, the best known was Stcherbatsky. The school, organized by Stcherbatsky, made some translations of very important Buddhist texts which were not studied anywhere else.

In fact, they organized the main international printing house for publishing Buddhist texts, called Bibliotheca Buddhica, to which many scholars from different countries contributed.

After the communists took power, everything was forbidden as it was regarded as religious propaganda. Most Orientalists were arrested, shot, or sent to concentration camps. Only Stcherbatsky himself survived, and then he died in 1942 during the war.

During the Soviet times, not one Buddhist publication was released. It only became possible again, after Gorbachev came to power, to have Buddhist publications, which I was heavily involved in.

Dr. Alexander Berzin, the founder of Study Buddhism, became the first Western Buddhist teacher to visit Russia, marking a new chapter as religious restrictions began to soften under Gorbachev. Could you share more about these early, secret teachings – what they were like, and what it meant for the Buddhist community in Russia at the time?

Dr. Alexander Berzin was like a Buddhist godfather to Russia. I managed to secretly invite him to Russia for the first time in 1987. We were only able to meet underground, very secretly. Not all Buddhists were invited to join, only the most “reliable ones,” the ones we could trust. A group of ten or so persons attended the teachings in Moscow and St. Petersburg, which he gave at private apartments.

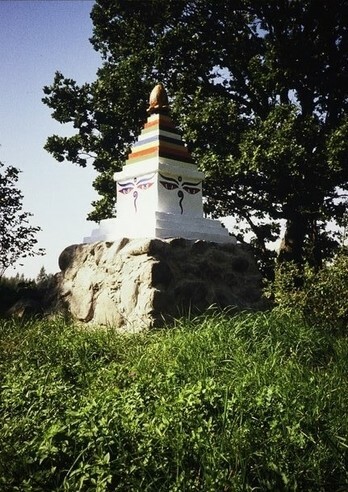

Alex was really impressed by our level, saying, "I think you are the most advanced group in the world!" Then, by the time Alex came again the following year, the situation had already changed. Now, we could rent a room and announce freely that there was to be a lecture on Buddhism. Then we travelled together, with me as his translator, all over the Soviet Union. We went to the Baltics, to Riga and Tallinn and other areas. We saw the first stupas built during the Soviet time in Estonia.

Later, we travelled to the ethnic Buddhist areas: Kalmykia, Tuva, and Buryatia. Alex's lectures were the first open lectures on Buddhism during the whole Soviet period. Many people visiting these lectures were reluctant to come as they didn't know if they would be punished: was it permissible to attend or not? So, they were very quiet, trying not to express any emotions.

However, immediately after Alex left, they applied to register Buddhist communities in Tuva, Kalmykia and Buryatia. Only after Alex visited! That is why I say he is the godfather of contemporary Russian Buddhism! Nobody was arrested, nobody was punished. Great enthusiasm grew. People liked to invite Alex because he gives clear explanations of the Buddhist teachings, and people value that.

Going back a bit, could you help us understand the state of Buddhism at the formation of the USSR – a period marked by the systematic destruction of monasteries and suppression of religion in Russia? What dynamics allowed Buddhism to persist for a time, and what ultimately led to its near eradication?

In the 1920s, the destruction of Buddhism didn't take place as fast as with other religions for specific reasons. Firstly, the Buryats, who were the most numerous Buddhist population in Russia in that period, were important people for the borders of Russia and for contacts with Asian nations. They would have been able to just move outside of the borders if they felt too heavily oppressed, and the Soviet government didn't want that. The Soviet government was also searching for a way for the army to go through Tibet to India, to attack the British in India. There were two or three secret missions sent to Tibet by the Soviet government back then.

So, the powers were reluctant to oppress Buddhism too much so as to not spoil relations with the 13th Dalai Lama. But by the beginning of the 1930s, when the Soviet government understood that the Dalai Lama would not cooperate and educated lamas in the Soviet republics revolted against collectivization, where land from the local people was forcibly taken to make "kolkhozes" or collective farms throughout the country, Buddhism was totally crushed. Almost all of the lamas were arrested, sent to concentration camps, or shot. No monastery remained intact.

For readers unfamiliar with the Buddhist history of Russia, could you introduce us to the three traditional Buddhist regions – Kalmykia, Buryatia, and Tuva – that later became part of the USSR? What unique role did they play within the broader Russian Buddhist community?

Before the Soviet period, Buddhism was practiced in three areas connected with people of Mongol origin, primarily the Buryats and Kalmyks. It is interesting that in Buryatia the official recognition of Buddhism dates back to more than 250 years ago. The Kalmyks were incorporated almost 250 years earlier into Russian territory than the Buryats were, and Buddhism was also recognized by the state then.

When the territory of Tuva was accepted as a protectorate of the Russian Empire in 1914, this third group of ethnic Buddhists in Russia – the Tuvans, who are the only Turkic people practicing Buddhism – joined the community of Russian Buddhist peoples.

In these three areas, Buddhism developed quite fast. Some intellectuals, writers, and noblemen were interested in the Buddhist teachings very much, so Buddhism started to spread among Russian people also. By the time of the Great October Socialist Revolution in 1917, we had around 20,000 monks and about 150 gompas or monasteries in these ethnic territories.

A Tibetan Buddhist temple was built in St. Petersburg, which was perhaps the first Buddhist temple in Europe as a whole. This temple was built partly for political purposes, as the Russian government was interested in widening contacts in Asia with the local people who were Buddhist. When the 13th Dalai Lama escaped from the British troops in Tibet, there was an idea that a temple would be built for him, and he could find temporary refuge in Russia. The mediator was the Buryat Agvan Dorzhiev, one of the Assistant Tutors and Debate Partners of the 13th Dalai Lama and a kind of envoy of his. It was perhaps Dorzhiev’s idea or at least one of his main objectives to build a decent Buddhist temple in St. Petersburg.

There is a legend that this temple was a Kalachakra temple, but I personally do not believe that. When the 14th Dalai Lama came to Russia for the first time and was told about this temple, which he actually even visited in 1992, he asked me, "Why do you say it is a Kalachakra temple?" I didn't know what to say, because it was just a kind of legend, and when I tried to find the origins of this legend, I didn't find any.

When Dorzhiev was arrested and died in 1938 in Stalin's Great Purge, his nephew, who officially inherited this temple, immediately wrote a letter to the government, saying, "Please take this temple and these counter-revolutionary people who live there," and the temple was given to the state. It was used for different purposes such as a laboratory for the Biological Institute and even as a radio station. In the 1960s, when George de Roerich returned to Moscow, he started campaigning to make better use of this temple. It was decided that the temple would be turned into a storehouse for Tibetan block prints and manuscripts, which until then had been kept at the Oriental Institute.

But de Roerich unexpectedly died, and the temple stayed as a laboratory for the Biological Institute for a long time, until 1987, I think. In 1987, the Leningrad Buddhists, during the Gorbachev era, claimed that the temple should be returned to the Buddhist community. We had some difficulties, but still we managed

to get it a year and a half after we applied. Since then, it belongs to the local Buddhists.

What unites the Buddhist traditions of Kalmykia, Buryatia, and Tuva, and what distinct cultural elements have emerged in each region? For instance, Buryatia and Tuva are thousands of miles away from Kalmykia, so how has this geographic separation shaped their practices over time?

Buddhist practices in Buryatia, Kalmykia and Tuva had much in common yet they had differences, of course. They had the same Tibetan Buddhist origin. But still, geographically being so far apart from each other they started to choose slightly different texts or wordings of those texts, or different melodies for chants. In Kalmykia, they also had a different calendar, which was not in use in Buryatia. Otherwise, the Buddhism practiced was very much the same.

The whole system of education, which is the basic foundation of the Tibetan tradition, was the same. This system was introduced in the Buryatian datsans, copied from the Gomang tradition and sometimes the Labrang tradition, and reproduced there. Students of Buddhism could receive degrees. Meanwhile, in Kalmykia, they didn't have this opportunity for a long time. Only in the beginning of the 20th century were two learning centers established.

In Tuva, they didn't have any learning centers at all, so they had to go to Mongolia for their studies. So, the level of development was different, but the tradition and practices were the same.

During Soviet times, how much of the Buddhist teachings and traditions were actively preserved in these regions and how did people maintain their Buddhist identity? Did any traces of Buddhist knowledge and practice remain intact?

The local people all identified themselves as Buddhists but at the same time didn't actually know much about Buddhism. They just had some memories. For example, when I was working at the museum in the end of the 1970s, we were giving tours around the museum, and I had a group of Kalmyks, who said, "We are Buddhists from Kalmykia, please show us the Buddhist exhibition." I was very excited. I thought, “How could I, a simple person, explain to Buddhist people about Buddhism?” But once we started the tour, I understood that they didn't know anything about Buddhism. Not even about the life of the Buddha! They just had this feeling that they are Buddhists, but they didn't know what it meant.

When I was travelling in Buryatia in 1981 as a researcher with the Museum of the History of Religion, it was explained to me that there were about 100 former lamas still alive. Only two or three of them were still performing rituals for the local people, and they were closely observed by the local KGB.

In Tuva, the situation was the worst, because Buddhism had been severely persecuted there. One wouldn't see anything Buddhist in people’s houses. When I visited former lamas in Tuva in the 1970s, there were only two places where I saw some Buddhist books in Tibetan and some painted images. The rest of the people didn't have anything Buddhist, but still they remembered, "We are Buddhist.”

How did Buddhism interact with traditional shamanistic practices? Was it coexistence, cooperation, or competition?

The influence of shamanism was quite different in all three Buddhist republics of Russia.

In Kalmykia, shamanism was already totally forbidden in the 18th century. Shamans had to bring their belongings and instruments to the main square to be burned. So, there was no contact with shamanism at all.

In Buryatia, there was competition between shamans and lamas, and this continues up to the present day actually! Recently, for example, when we had forest fires in Siberia, shamans and lamas were performing their own rituals to bring rain, to stop the fires. I don't know who did better!

In Tuva, there was no competition at all, and in fact there was a friendly, close relationship between shamanists and Buddhists. The number of Buddhist teachers and shamans was approximately the same. There were even special training centers in the Buddhist monasteries for the shamans. They were asked to go around the villages and preach some basic Buddhist ideas and to spread Buddhist values. Very often, families comprised both lamas and shamans, who were very closely related.

Tibetan medicine has traditionally been a part of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. Was this system integrated into the Buddhist practices of Kalmykia, Buryatia, and Tuva, and how was it adapted to meet local needs?

Traditional medicine in the Buddhist areas of Russia had its roots entirely in Tibetan medicine. In Buryatia, they started to practice traditional medicine very early, sometime in the beginning of the 19th century, maybe earlier even. There were centers for studying medicine, such as in Atsagat Datsan and some other places.

They borrowed the tradition from Mongolia, so in Buryatia they had to substitute certain ingredients in medicines.

So, while it was not exactly the same as Tibetan medicine, the theory was the same and it was widely practiced in all the Buddhist republics. I don't know about Kalmykia, but in Tuva and Buryatia, it was actually the main medical service available to people. In Buryatia, there were at least two schools, or manba datsans, where traditional medicine was taught and studied according to the books of Tibetan medicine.

Given the historical influence of Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhism in Kalmykia, Buryatia, and Tuva, did each region have its own spiritual head? Was there any interaction or cooperation between the local leaders, and what role did figures like the Dalai Lama and the Jetsundamba play in their spiritual hierarchy?

The people in Buryatia, Kalmykia and Tuva always remembered that they were subordinate to Mongolian Buddhism, and further up, to the Dalai Lama in Tibet. All the ethnic Buddhists knew of the Jetsundamba (the title given to the spiritual head of the Gelug lineage of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia). It was unanimously accepted that these two people are the real heads of the tradition.

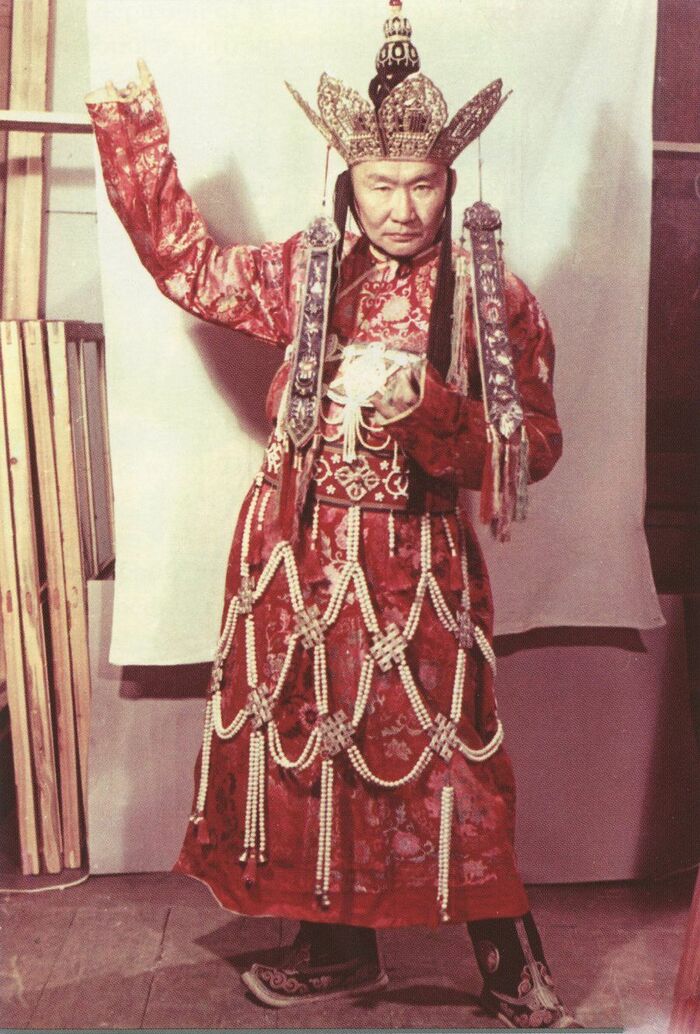

Yet they had their own heads too. In Buryatia, this was the Bandido Khambo Lama. In Kalmykia, it was Shajin Lama, or the Lama of the Kalmyk people, as it was rendered in Russian. But in Tuva, they didn't have one. They had one Khenpo at the monastery of Chadan Khuree, who was considered the most authoritative. But he didn't possess any administrative powers in Tuvinian Buddhism, just moral authority. Religiously, they were subordinate to Jetsundamba Khutuktu, and then to the Dalai Lama.

In fact, the leaders of Buryatia, Kalmykia and Tuva didn't have much contact. They lived so far from each other and travelling in that period was difficult. They were mainly interested in the pilgrimages to the holy land of Mongolia or Tibet. So, contact between them was very rare as far as I know.

The situation has changed, and of course spiritual heads now have contact with each other, but they have not really joined together as one community, even if their practices and traditions are so similar.

How closely connected, if at all then, were the monasteries in Buryatia, Kalmykia, and Tuva with those in Tibet and Mongolia?

The monasteries of Buryatia and Tuva were very closely connected with Mongolian and Tibetan monasteries. In fact, Tuvinian Buddhism was a part of Mongolian Buddhism in the minds of people and was subordinate to Jetsundamba Khutuktu, also known as Bogd Gegeen, the head of Mongolian Buddhism.

The Buryats, however, were not allowed to have their head outside of the country, so they had their own centralized organization, headed by the Bandido Khambo Lamas. In Kalmykia they also had their own centralized Buddhist organization. They were not subordinate to either Mongolian or Tibetan leaders, but the system of education was always Tibetan. And not just Tibetan, but traditionally in Buryatia, Kalmykia and Tuva, they were all linked specifically to Drepung Gomang monastery in Tibet, which educated monks from Mongolia and Mongolian tribes in Russia. So, the connection was very close.

How would you describe the current status and revival of Buddhism in Russia today? Reflecting on the experiences of the last century, is there hope for the future?

The situation of Buddhism in Russia at the present time is very multifaceted and not so easy to generalize about. During his visits in 1991 and 1992, His Holiness the Dalai Lama said that when he saw all the destruction, he thought, "Russia will become one of the main countries of Buddhism in the near future." I couldn't believe my ears! I asked him if he really meant that, and he said he did because the enthusiasm of people was so great, among both ethnic and non-ethnic Buddhists.

From 1990 onwards, Buddhist centers started to spring up in many places all over Russia. Not only in the big cities, but also in smaller ones, primarily in the ethnic areas of Buryatia, Kalmykia, and Tuva. Now, we have more than 200 groups, all over Russia.

In the Tsarist time, we had only one version of Buddhism, which was the Gelug school's Gomang tradition. Now, you can find anything. Not only Tibetan Buddhism, there's also Theravada Buddhism, there are Vietnamese and Burmese groups, and the whole spectrum of Buddhist teachings.

Thank you, Andrey, for sharing your invaluable insights and personal experiences. It was fascinating to gain this rare glimpse into the resilience and revival of Buddhism in Russia!