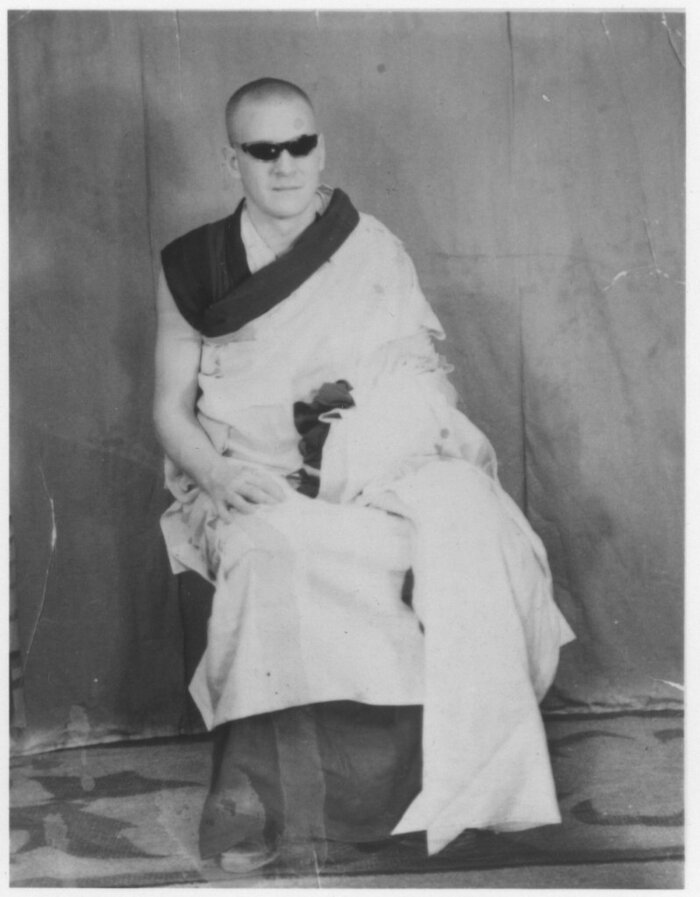

Professor Robert Thurman’s reputation as a trailblazer in bringing Tibetan Buddhism to the West precedes him. A student of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and a scholar with decades of teaching at Columbia University, his path to Buddhism began with his ordination as the first Westerner to become a Tibetan Buddhist monk, personally ordained by the Dalai Lama in 1965. Though he eventually returned to lay life, this experience shaped his perspective on how Buddhism can bridge the spiritual and the secular, the ancient and the modern.

60 years later, his passion for making the Buddhist teachings accessible without diluting their essence has been a hallmark of his work. From ethics and compassion to mindfulness and meditation, he explains how these principles can be integrated into contemporary life without requiring monasticism.

In our conversation, Thurman unpacks Buddhism's unique approach to understanding reality, emphasizing its empirical, rational nature. Drawing on Buddhist history, he explores the pragmatic flexibility of the tradition, from its scientific approach to exploring the mind to its adaptability in different cultural contexts. He also reflects on the relevance of the middle way as a remedy for the extremism and divisiveness of modern society. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: You’re a renowned professor, so let’s begin with education, something the Buddha placed great importance on. How does Buddhism view education and its purpose in our lives? What’s the value of studying Buddhist philosophy?

Professor Robert Thurman: Everything is laid out in the Buddha’s Eightfold Path, which is the fourth of his Four Noble Truths. The Eightfold Path has eight branches that fit into three higher educations. Śikṣā means education or learning something. Atiśikṣā means intense education or higher education. The three higher educations are: education in ethics, education in mind (the control and understanding of the mind), and education in wisdom, which involves the investigation and exploration of the nature of reality.

Higher education in ethics corresponds to politics, sociology, society, and so on. Higher education in the mind is related to psychology, but it also covers something we don't focus on much in the West—training in how to use the mind. Finally, the most important of these is the education of wisdom, which involves exploring reality to achieve liberation and freedom from suffering. This is, in a way, a scientific process.

You are studying an ancient way of examining the nature of reality with the mind as the primary tool. It isn't a spiritualistic or non-rational pursuit or based on blind faith, as people often assume religion to be. Instead, it is a critical, rational, logical, but also empirical, experiential, and perceptual training in understanding reality. Learning about the use of the mind is essential for improving your most important investigative tool—your own consciousness. Ethics, meanwhile, deals with how you should behave to avoid a turbulent lifestyle of conflict with others by being more other-sensitive, which means being ethical and “other-regarding.”

Studying Buddhism improves your ability to use your mind to investigate reality, to see how others have explored it, and to understand the theories they developed. Buddhist scientists, philosophers, yogis, and great masters like the Buddha did not develop dogmatic theories about the nature of reality. They understood that reality is beyond being pinned down by theory. Theories are helpful for orienting yourself toward experiencing and investigating reality, but they cannot fully capture its nature. Reality is beyond theory, though it is not beyond experience.

We do experience reality, but we tend to misinterpret our experiences. This was Buddha’s insight, which he called ignorance or mis-knowing. The goal is to correct this mis-knowing to fully and accurately know the nature of reality—a process that, according to one Buddhist theory, is entirely achievable.

The best way to study Buddhism is not as a religion, but as a set of scientific theories, practices, texts, and traditions you can use to explore reality on your own.

That’s a fascinating way to look at it, but for many people, Buddhism still seems more like a religion than a science. How do you see this? Can Buddhism be both?

I would not say that Buddhism is a science. The “ism” part relates to being a religion, like Hinduism, Confucianism, or Daoism. So “ism” automatically assumes a religion. I agree that Buddhism is a religion for those who do not use its educational system very fully.

In Asian history, most societies for a long period of time were semi-literate or entirely non-literate. Later, once Buddhism became established in these societies, Buddhist monks and nuns were literate. For an illiterate farmer who had been taught a sermon by a Buddhist monk or learned basic ethical precepts, they might observe the example of Buddhist monks being self-restrained, not over-emotional, and not angry. For them, it’s a religion. They believe the Buddha must have been a good person, perhaps enlightened—whatever they think enlightenment might mean. They have divinities. Buddhism never took people’s divinities away from them, but it de-absolutized them, relativized them, and perhaps made them less fanatical.

So, for them, it’s definitely a religion. But was Buddha’s main purpose to found a religion? I don’t really think so. He was rebelling against what I call “Vedism,” which held that the Vedas were the word of God. They followed priests and injunctions without the idea that one should rationally understand them. The Buddha rebelled against that. He believed a human being could understand their world and their reality, and he was definitely trying to do so.

Unfortunately, reality is beyond encapsulation in any theory. Theories are useful, however, in giving you an orientation toward developing valid experience. But ultimately, experience rules.

In the modern world, religions are all rubbing up against each other in the same cities, the same communities, the same towns. Religious pluralism seems to be the only social practice conducive to social harmony. The leaders of Buddhism I respect most—those who are the most reasonable about the reality of modern societies—are like the Dalai Lama, who says he doesn’t want to convert people to Buddhism. It’s not necessary to try to convert each other.

We should be imploring secularists not to try to convert people to their materialist theories, but rather to see the good things they have achieved with their own perspectives. Share those achievements, and let others adopt them if they choose. Similarly, we offer the services of Buddhist sciences that could help in a scientific approach toward the nature of reality. That is to say, our activity is focused on seeking to know what is real, to differentiate it from what is unreal, and to develop wisdom. This wisdom is ultimately scientific in the sense that it is oriented toward understanding reality.

The middle way is such a central teaching in Buddhism, but it feels particularly relevant now, in our increasingly divided world. Can you explain what the middle way means and how it applies to today?

There are at least two kinds of middle ways. One of them is the middle way that the Buddha first mentioned after his enlightenment. He said, “When I was a prince, I was very self-indulgent. The world was very indulgent with me. I experienced every pleasure; everyone catered to my ego and what I wanted. So, I was overindulged with sensory pleasure. Then, when I became an ascetic, a seeker, I went to the opposite extreme and decided my body was the problem. I was mortifying my body to the absolute, and by inflicting pain and damage upon myself, I thought I would discover whatever enlightenment there was to be found in pain. I was extremely self-mortifying and overly ascetical.”

He went on, "My first middle way was the middle way where I restrained myself from excessive sensory indulgence, and I also restrained any tendency to self-punish or self-mortify.” That is the first middle way.

The second middle way was unpacked in the Transcendent Wisdom Sutras (Prajnaparamitas) and even the Pali suttas. This is the middle way between absolutism, or what is sometimes called eternalism (when you focus on the impermanence–permanence duality), and nihilism, where you believe that nothing exists at all. These are two extremes of worldview. Absolutist theism, absolutist self-centrism—there are many ways of seeing things as absolute. The opposite is nihilism, where you see everything as dissolving into nothing, with no consequences for anything.

The middle way between absolutism and nihilism is a good kind of relativism, where things are relational. There are strong rules and relative absolutes within that relativity, but they are never absolutely absolute. And there is no such thing as “nothing”; everything is relative. Nothing is the only thing that doesn’t exist—there is no nothingness, in other words, except as a concept.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on anger. It’s often seen as one of the most destructive emotions, but can it ever be helpful? For instance, can anger fuel positive change?

Anger has a degree where you lose self-control and blow up. Unfortunately, when you're angry, you crash into a situation without being under any kind of control. Anger sweeps you away from your normal rational self-control, and you become possessed by it. Studies today suggest that when you are angry, you lose 85% of your good judgment. Shantideva also agrees that your body, mind, and speech become tools of your anger, and anger dominates you.

Your anger becomes like a demon, compelling you to say things you don’t mean, deeply hurting people, and leaving you feeling regretful afterward. You might do physical things and hurt people you didn’t intend to harm. You lose control—you hit people, hurt people, or even kill people. Or you hurt yourself. You might do something like bang your head against the wall or angrily drive your car into something and kill yourself. You break things that you value and feel regretful afterward.

Mentally, anger creates a hostile mind, where you destroy something or someone in your imagination. All of these outcomes have very negative results for you and for the situation. They don’t lead to good results. From the Buddhist perspective, anger never helps. It is always destructive.

However, if you define anger as a kind of heat or vigor, a strong energy that arises when you see something wrong and want to fix it, then there can be a positive side. This kind of righteous, strong feeling about ethics or helping others—thinking, “This won’t do, this won’t stand”—allows you to remain able to make judgments.

This can be a positive determination. There can be willpower, where you remain in charge of your emotions. Shantideva says, “Intervene in the situation while you’re still cheerful.” Your good cheer is the source of positive actions, so don’t let it be eroded by frustration.

When you start feeling frustrated, act on it. If there’s nothing you can do about the situation, Shantideva advises, “Get away from the situation.” It doesn’t help to blow up, become really angry, or freak out because you feel impotent in a situation. Just move on—leave the situation.

Of course, the ultimate way of overcoming anger is to no longer feel angry because you feel sorry for the people who harm you or cause you anger. You may still resist them and act forcefully, but you won’t feel anger because you’re not trying to eradicate them from the universe. Instead, you’re just trying to stop them from doing something harmful. You recognize that there’s more to them than their anger or actions.

The one thing Shantideva says you’re allowed to be angry with is anger itself. You’re destroying the fury that causes you to act non-relationally. The people who are most violent and destructive when they’re angry are those who maintain a sense of absolute identity. Their inner voice says, “You’ve got to get that person. You can’t be in the same world as them. This town isn’t big enough for the both of us.”

These individuals are caught up in the self-absolutizing habit pattern—what I call the “identity habit.”

You were personally ordained by His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1965, becoming the first Western Tibetan Buddhist monk. Later, you disrobed after meeting your wife and returning to the USA. How essential is monastic life for someone committed to the Buddhist path?

You have to, of course, be in a society where people will support your life, feed you, offer you shelter, and allow you freedom from social duties in order to live that way. You need to have a level of prioritization, even if you are not a formal monk or nun, where you become determined that this is the high priority of your life: “I’m going to develop my compassion. I am not going to give in to my anger, my lust, my greed, my envy, and my pride.” You make these resolves and prioritize undoing the things that cause suffering and hold us back from enlightenment, which means awareness of reality.

But is this possible in the modern economy, especially in countries where monks and nuns are not really respected? In societies that believe the only valuable goods in life are material things you have to acquire during this lifetime, there won’t be social support for people who prioritize their spiritual evolutionary development. Therefore, in those societies, I think it would be possible for a person to earn a livelihood, save enough wealth, and then be able to go on retreat year after year, living as part-time monks or nuns, or as monks or nuns for a few years.

In that case, you don’t need to be a formal monk or nun. In a way, for some period of time, you can live as the equivalent of a monk or a nun.

I always say, when people ask, “Has Buddhism reached the West?” that Buddhism will have truly reached the West when Buddhist monasticism is fully respected and supported by Western Buddhists, at least. If even Buddhists don’t support it, then I would say Buddhism is not really present. Buddhist ideas and practices might exist, but Buddhism itself isn’t truly there until there is genuine respect for the vocation of the monk and the nun.

Buddhist monasticism has a rich history, but I imagine its relationship to sexuality and sensuality can be complex. How do Buddhist monks and nuns approach this aspect of life? Can monasticism accommodate or work around it?

In Buddhist history, especially in the latter phase of Indian Buddhism and in Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhism subsequently, certain practices could sometimes become obstacles for some monks and nuns—for example, practices related to sensuality. Therefore, there is a tradition, as in the case of Naropa and many other famous adepts in India, where individuals resigned from monasticism because they were infringing on certain basic rules, often those related to sensuality.

In such cases, the vocation of being a monk or nun is not necessarily permanent. However, these cases are very carefully noted in the tradition as exceptional. Otherwise, young people—especially when they are sexually vibrant—might think, “I can have a girlfriend or boyfriend and still focus on my spiritual practice.” If this were widely accepted, many would leave the monkhood.

Those who leave at that stage are often not yet at the level required to maintain such a practice. There is a clear definition of what that stage is. They need to have already developed a visceral understanding of selflessness, emptiness, identitylessness, or realitylessness—concepts central to Buddhist philosophy. They need to have at least a taste of this understanding, if not the full realization, which comes only with full enlightenment. Additionally, they need to have a positive attitude, embodying the bodhisattva spirit: wanting to make love the highest priority, being loving, gentle, and tolerant toward all beings, and refraining from harming or violating anyone in any way.

In the Buddhist tradition, even if one engages in sensuality, which a monk or nun typically would not, it is done with the purpose of attaining enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. It is about becoming a perfect Buddha for the benefit of all beings and accelerating that evolutionary development—whether in this life, future lives, or over several lifetimes.

If someone has been a strong monk or nun and then reaches a stage where they need to interact more with others in a less rule-governed way, it is acceptable for them to resign as a monk or nun.

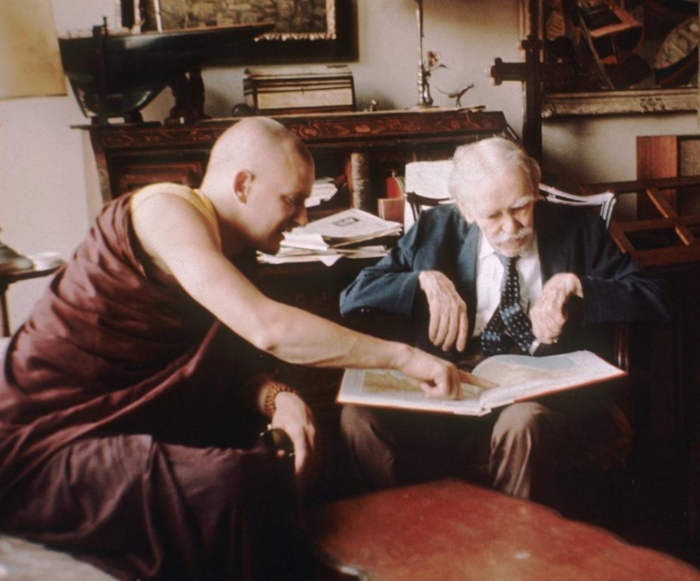

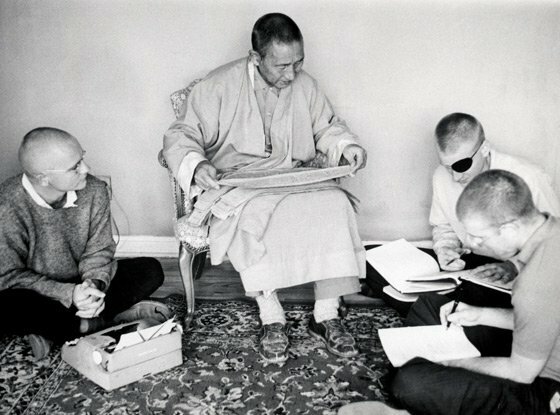

Geshe Wangyal, often referred to as “America’s first lama,” founded a Buddhist center in New Jersey in 1958. You and Study Buddhism’s founder Alex Berzin both studied under him in the late ’60s and early ’70s. He seems to have had a profound impact on your life. Could you tell us more about his influence?

Geshe Wangyal was a wonderful mentor and a wonderful model. Meeting him in the 1960s was a total earthquake for me.

He had a geshe degree and was very learned. In fact, he had taught language at Columbia University before I knew him. He wasn’t trying to create an empire of Dharma centers. He was truly there to benefit those who sought his help. He didn’t think everyone should be a Buddhist either. He would tell people to go and see their rabbi or go back and help their mother. He didn’t try to recruit people to become monks or nuns, but he wouldn’t oppose it if he thought it would be helpful for them.

In my case, he knew I sincerely wanted to be a monk, but he also knew I wouldn’t have enough support, and that it wasn’t my destiny to follow that path. He was clairvoyant—I know that for a fact. I could tell by the way he intervened in various situations in my life. He always knew exactly what was going on in my head. He was truly a great person.

I’ve met holy gurus who are luminous at times, but often you feel like a little nothing next to them, and they are entirely focused on themselves and how you fit into their agenda. I was always suspicious of that dynamic. I didn’t want to take on the role of a follower or devotee, and I didn’t want to be “religious” in the way many people think of religion—following someone else blindly, expecting them to solve your problems.

Geshe Wangyal wasn’t like that. He didn’t have an agenda for me beyond seeking an English teacher for his young lamas who had been sent to his lamasery in New Jersey to learn English. The goal was for them to serve as interpreting monks for the Dalai Lama.

He was centrifugal as a teacher. People would come to him, and he would serve them as best he could, then encourage them to return to what he felt they really needed to do in life: their jobs, their families, or their communities. He wanted them to integrate into their own environments, whether they were Christian, Jewish, Muslim, or something else.

He was very much like His Holiness the Dalai Lama in that way. His significance is immense; he’s a kind of emanation of the great Avalokiteshvara, just like His Holiness.

Thank you so much, Professor Thurman, for your time and sharing your insights and experiences with us!