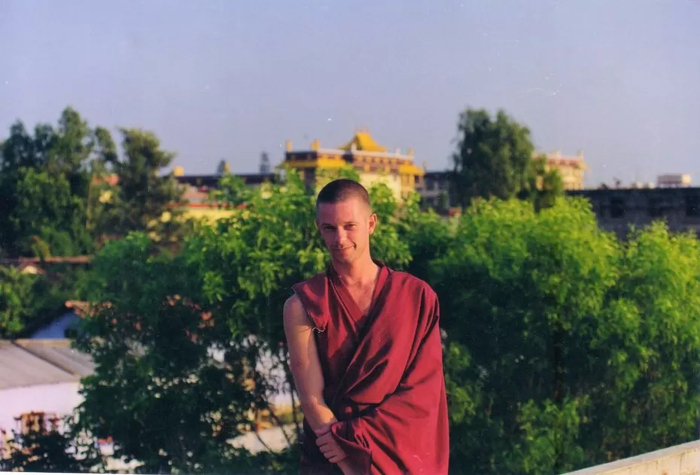

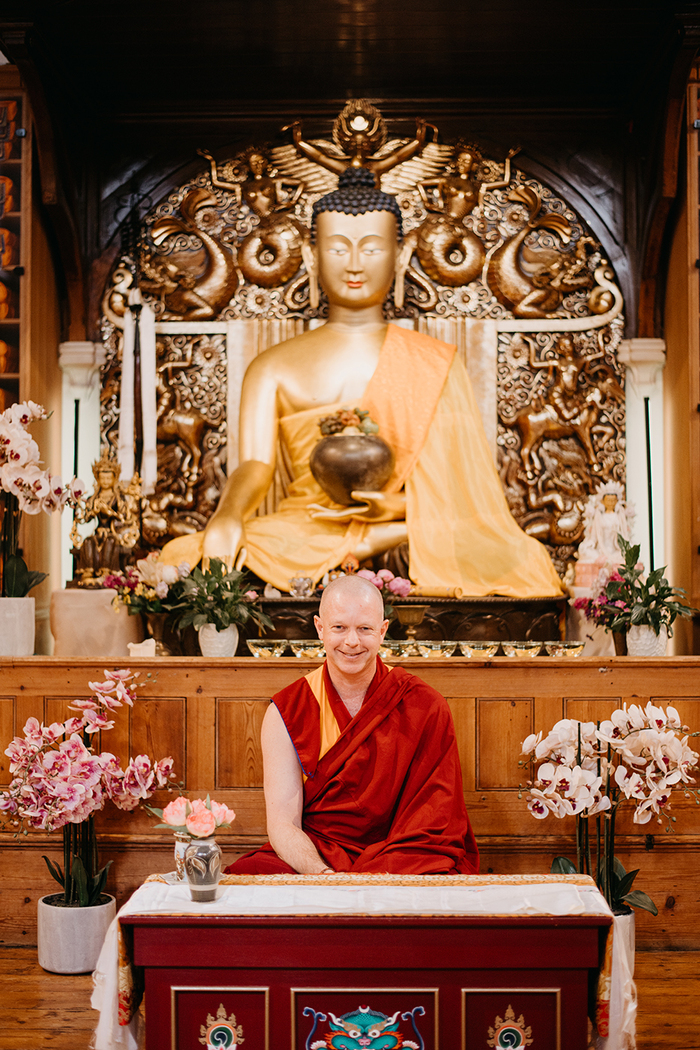

Situated in the heart of London’s Elephant and Castle, Jamyang Buddhist Centre is a sanctuary of Tibetan Buddhism, a place where people from all walks of life can discover ancient wisdom – and the place where I first truly encountered the impressive depths of the Buddhist teachings more than two decades ago with Geshe Tashi Tsering (read his interview here). I visited in the summer of 2022 to meet with Jamyang’s new resident teacher, Geshe Tenzin Namdak, for an in-depth interview on his life and experiences.

Born in the Netherlands and with a background in mathematics and hydrology, Geshe Namdak embarked on a path that few Westerners – or even Tibetans for that matter – have even contemplated, let alone completed: the grueling 20-year Geshe degree at Sera Jey Monastic University in India. This degree, which we go into during the interview, is a monumental undertaking. Imagine studying multiple doctorates while living in the austere conditions of a traditional Tibetan monastery, and you’ll get the idea. Geshe Namdak became the first Westerner to complete the degree at one of the three traditional “great monasteries” – in this case, Sera Jey.

In our conversation with Geshe Namdak, we explore his extraordinary journey, with an admission from that start that he never initially aspired to even become a Geshe. We move on to speak about the three poisons and how to overcome them, why taking vows can be so beneficial, and dive into one of Buddhism’s most profound topics: ultimate reality. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: How did you come to undertake the unique challenge of completing the 20-year Geshe degree at Sera Jey Monastic University in India, and what were the key challenges you faced in persevering through this rigorous program?

Geshe Namdak: I never wanted to become a Geshe, but my own teachers encouraged me to pursue this path. It has the benefit of achieving something substantial, in that it's like a university degree where you feel you've accomplished something significant. However, the Geshe degree is more than just a title; it's about making lasting imprints on your mind over 20 years through studying the various subjects of the Buddhist doctrine.

The 20 years of the Geshe study program is a life-transforming process. It's essentially like being in retreat for two decades. It’s challenging due to its intensity, but it’s also transformational because you study the mind and its philosophy. Though it may seem lengthy, if enlightenment is considered to be many eons away, investing in study is essential. You learn to deal with destructive emotions and work towards eliminating ignorance.

In the monasteries, you find all types of people, and not everyone completes the entire program. Some may drop out halfway. At Sera Jey Monastery, we had about a 75% dropout rate over the 20 years; for Westerners, the dropout rate is slightly higher. Not everyone can endure it because the discipline it requires and the studies are demanding, and each day feels like a daily exam. It’s a rigorous lifestyle, but if you adapt, it can be very beneficial. Anyhow, many of those who do not pursue in-depth studies and drop out contribute to the monastery and community in other ways. There are opportunities to help with health-care centers, libraries, or interfaith events and so on. There are various ways to live a monastic life.

Could you walk us through the curriculum covered during the Geshe degree?

We study epistemology, which is essentially the language of philosophy used to analyze concepts. I have a background in mathematics and statistics from my studies in hydrology, but epistemology is an entirely different field. In epistemology, it is crucial to understand the exact meaning of each term, to memorize their definitions, and thereby understand what a person means by a particular term. This allows for precise and in-depth debate.

Apart from epistemology, we study the Pramana texts, as we call them, and the Prajnaparamita, or Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, for about seven years, depending on the monastic institution. The Perfection of Wisdom Sutras teach the stages of the path to enlightenment, or what we call the grounds and paths. They form the building blocks for what we refer to as the lam-rim, a practical summary of the entire Buddhist path. The Perfection of Wisdom Sutras are fundamental to our practice, providing a clear map of what we need to do until liberation and enlightenment.

Regardless of the path you follow, wisdom is needed to eliminate ignorance. At Sera Jey monastery, we studied the view of ultimate reality for four years because the teachings on emptiness are among the Buddha’s most important teachings, as they address ignorance, the root of samsara. Following that, depending on the monastic institution, you study monastic discipline and rules, known as Vinaya, for three years, as the Geshe and Geshema programs are designed for monks or nuns.

We then study the Abhidharma for about two years. The Abhidharma mainly covers karma, various aspects of consciousness and mental factors, and how they interact with each other. It explores their definitions, nature, and functions, providing insights into Buddhist psychology.

You've mentioned that epistemology is crucial for a clear and accurate understanding of Buddhist concepts, especially in the context of debate. Since debate is a fundamental part of Tibetan Buddhist monastic training, could you explain what makes this practice so beneficial?

Debate, especially in the Tibetan tradition, is a very essential aspect of the path. For example, in the monastic system, we might have two or three classes of philosophy each week, each lasting one to one and a half hours. For the rest of the time, it’s hours of debate every day.

Discussions are beneficial because talking through and analyzing the material provides more clarity and helps with retention. Most of the traditional texts we study are based on a debate format, so missing out on the debate means missing certain aspects of the texts' explanations. In this regard, debate can be extremely beneficial.

You need to invest time into it because to truly benefit from a debate, you must memorize terms and definitions and be very familiar with the material. You can’t bring a book to the debate courtyard; everything has to come from the mind.

When you read the root text, the commentaries, and attend teachings, you get an idea of the interpretations of the more difficult sections in the text. Then, when you sit down for a debate and someone asks about the interpretation of a point, such as, “What is the nature of ultimate reality?” you delve deeper. The more detailed the discussion becomes, the more interpretations are possible. You might think you understand it and provide an answer, but your classmates, especially those sitting on the side, may say, "This is going in the wrong direction. I need to correct him!" They then get up and present different forms of logic. Debate, therefore, is not only a good practice for clarifying aspects of the teachings but also for managing the ego.

In debates, scriptural references are important, but reasoning is crucial. Various scriptural references may differ, especially when combining different tenet systems. Different scriptures offer different perspectives, and you need to analyze them. Thus, reasoning is actually much more important than mere scriptural reference.

That’s why logic is so incredibly important in this tradition. As the Buddha himself said, "Don’t accept my words just because I am a respected person. You should analyze my words like you analyze gold by breaking it, rubbing it down, and melting it," meaning you should use various forms of valid cognition and reasoning to determine whether what the Buddha says is true.

Having studied at Western universities and spent decades as a monk, how would you describe life in a monastery? In what ways does it differ from a typical university education?

If I compare life in the monastery to life at university, it's more intense because you get up early and go to bed late. Of course, we had a bit of a siesta after lunch due to the climate, but the day is full of pujas, prayers, studying, and especially debating. As I just mentioned, debate is like a daily exam, so if you didn’t study or memorize well that day, you’ll have a hard time in the debate courtyard!

Additionally, you live with roommates in a small room, so there is no privacy at all. For a Westerner, this can be quite challenging initially. You can never say, "No, I want to be by myself." That’s simply not possible. You’re always with people, in a real community. You need to get used to that, but it provides incredible support. It’s much easier to study and keep going when the energy is high with many people.

Initially, the conditions were not as good as they are now. We had only a water pump, so there wasn’t a shower in our compound – just a bucket to wash with. Another challenging aspect at the beginning, but one that brought great benefit in the long term, was that Tibetans are very good at teasing each other, especially regarding the ego. They would go deep, almost to the point of making you angry, then say, "Hey, look, there it’s coming!" The more uptight you are, the more you become the center of attention. But it’s a very playful way of teasing the ego. The culture itself has a very relaxed atmosphere, though it’s also quite tense. However, people know how to relax by teasing each other and joking around.

Also, at first, it was quite challenging for me because Westerners are behind language-wise. I had studied a bit of colloquial Tibetan in Dharamsala, but debate uses a fast-paced, specialized language.

You ordained almost 30 years ago. What advice do you have for someone who wishes to become a monk or nun?

You shouldn't rush into becoming a monastic. It should be grounded in a thorough understanding of the lam-rim, or the stages of the path to enlightenment. There should be a form of renunciation born from understanding the nature of suffering and recognizing that you can address this within monastic life.

It’s best to live in a community as a monastic since you need support, especially at the beginning. I have been involved with a project with His Holiness the Dalai Lama's Private Office to screen Western candidates for ordination with His Holiness. The rules have become stricter over the years, which is important because you don’t want to rush into such a decision. One of the prerequisites is to stay in a community.

Some think becoming a monk or nun is easy, but staying ordained and training according to the discipline takes effort. When you become a monk or nun, it must come from within yourself. You shouldn't be forced by someone else; it has to be a genuine motivation, based on understanding the lam-rim and the path to enlightenment to some extent. Alongside motivation, it is essential to have faith in the ritual that establishes the vows. You must be aware when the vow is established, and then you can rejoice. His Holiness always emphasizes that it is crucial to rejoice and feel incredibly fortunate when you ordain, as there is an unbroken lineage of vows for self-liberation all the way from Shakyamuni Buddha to the present day.

You just mentioned vows. Could you explain what a vow is and how it can be beneficial? Are vows something that laypeople should take as well?

There are a variety of vows for both monastics and laypeople. Generally speaking, vows are classified into three categories: vows for self-liberation, bodhisattva vows, and Vajrayana vows.

A vow is essentially a promise not to engage in negative behavior. The Buddha had profound insight into karma, which is not something magical or fabricated but rather a principle of interdependence. There is dependent origination within the continuity of consciousness. Just as external dependent origination involves a seed growing into a plant and producing fruit or flowers, internal dependent origination occurs within the mind. This cause-and-effect relationship produces specific results. For example, getting angry leads to disturbance. This cause-and-effect relationship within the continuity of consciousness is what we call "karma." The Buddha understood this law of cause and effect and taught that by living in accordance with it and creating the right conditions, you can generate happiness, especially by abandoning the causes of suffering. Vows are thus a way to help abandon these causes of suffering.

A vow is not a form of imprisonment. Living according to vows actually brings more happiness because it clearly defines behaviors you should avoid. For instance, you might wish not to engage in the act of killing, whether it's a human being or a mosquito. Making a promise not to do so turns that wish into a vow.

Often, people think, "Vows are so difficult to keep!" However, it's not that difficult at all: not killing, not stealing, not engaging in sexual misconduct, not lying, and not taking intoxicants. By promising not to engage in these actions, you make a stronger commitment to yourself and increase the number of good deeds you perform. If you study the vows carefully, you'll find they are simply about not harming others or yourself. Vows are methods to help us become happier and to progress on the path to enlightenment.

The teacher-student relationship is central to Tibetan Buddhism. What are the key benefits of having a spiritual teacher, and how can someone seeking to deepen their Buddhist practice find the right teacher?

The teacher-student relationship is very important in Tibetan Buddhism. In the Buddhist path, we have a practice called guru devotion or relying on the virtuous friend. The term "virtuous friend" is actually the literal translation of the Tibetan "gewai shenyen," which essentially means teacher. Why “virtuous friend”? Because it is through the teacher that we learn how to transform our mind. This aspect is quite important in Buddhism.

You can find this practice in Asian cultures, though it is now somewhat diminishing. In earlier times, there was always a great deal of respect for the teacher, as they were the source of knowledge. In Buddhism, being an ancient and traditional system, it is crucial to respect the person who helps you eventually transform your mind. One aspect I always find inspiring is seeing the teacher as an example or manifestation of the teachings. For instance, observing His Holiness the Dalai Lama, you see a genuine embodiment of love, kindness, compassion, and wisdom. If you find this inspiring, you develop trust in this person, who has demonstrated realization of the teachings. Because of this trust, you can rely on them for advice and further instructions. Faith in the teacher, however, is not blind faith. It is based on reasoning, with the understanding that this person can help you comprehend the Dharma.

To develop a relationship with a teacher, it is important to analyze and evaluate them carefully and over time. You should ask: does the teacher possess the qualities described in the lam-rim? Are they practicing what they preach?

You do not need to be in direct contact initially. You can simply attend a lecture and observe. Over time, you can build a relationship by asking questions and noting how the teacher responds. This is a slow process that should not be rushed. If a genuine connection is established over time, there can be great benefits.

The training you underwent traces back to Indian monastic institutions like Nalanda University, which for nearly a thousand years shaped Buddhist philosophy, logic, ethics, and contemplative practices. How is the tradition of Nalanda connected to Tibetan Buddhism today?

Especially in northern India, there were monastic universities like Nalanda, Vikramashila, and Taxila. These were among the earliest universities in the world, where an in-depth study of philosophy and psychology, primarily within the Buddhist tradition, took place. At that time, many students from various countries came to study Buddhism there.

There are essentially five main topics of the sutra system of the Nalanda tradition that were taught, which are the topics I described earlier as part of my Geshe degree training. Nalanda had a rich tradition in Pramana, or logic and epistemology, which is essentially the language used to describe Buddhist philosophy and psychology. Just as mathematics is fundamental in science, epistemology is fundamental in the Indian Buddhist tradition. The Perfection of Wisdom Sutras outline the path to liberation and enlightenment. Madhyamaka philosophy, or the middle way philosophy, provides understanding of ultimate reality, selflessness, and emptiness. Then we have discipline, or Vinaya, which covers morality. The fifth system, Abhidharma, explores various aspects of the mind and mental factors. Additionally, Vajrayana was also studied at Nalanda, carrying a rich tradition of the complete teachings of the Buddha preserved in Sanskrit during the early days.

The entire Nalanda tradition was originally in Sanskrit and was later translated into Tibetan. That’s why, although we refer to it as "Tibetan Buddhism," it is actually the Nalanda tradition that has been preserved by the Tibetans over many generations. We should be very thankful for this preservation, as it represents the complete teachings of the Buddha.

The Tibetan language itself is similar to Sanskrit in that a few terms can summarize or contain much more meaning. We sometimes struggle to translate certain terms into European languages because we can never fully cover a term; it always requires additional description. This highlights the extreme richness of the Tibetan language.

However, to benefit from knowing Tibetan for studying Buddhism, one must invest a significant amount of time. Studying Tibetan thoroughly, both colloquial and classical, is essential. We are fortunate to have these complete teachings, thanks to the Tibetans, who have kept this rich tradition alive and preserved the transmissions and initiation rites.

What are the “three poisons” that we often hear about in the Buddhist teachings, and how does meditation help to counteract them?

We use meditation to eliminate destructive emotions and mental states, which in Buddhism are referred to as “the three poisons”: anger, attachment, and ignorance.

Attachment is a mind that overestimates the qualities of its object – qualities that are not actually present. You create a mental image, believing that the qualities you attribute are inherently part of the object. You mentally construct this image and then perceive it as the object itself. When the pizza arrives and it’s not as warm or as tasty as you expected, you feel disappointed. When you overestimate the qualities of the object of your attachment and your expectations are not met, you experience distress. You don’t find what you’re looking for.

Anger is another poison. Anger is a state of mind that does the opposite of attachment. It exaggerates or superimposes faults onto the objects. These are faults that you mentally create about a person or situation. You choose not to see the good qualities of the person and focus only on their faults.

Attachment and anger are states of mind that are out of alignment with reality, which is why they cause problems. This is even truer for the third poison, ignorance, which is a fundamental misunderstanding of reality. This can manifest in modern mental issues like anxiety, fear, and depression, where you believe in a reality that doesn’t actually exist, and this misunderstanding of reality leads to problems.

Ignorance is the root of all suffering. Why? Because anger and attachment are rooted in ignorance, which is based on the concept of "I" and "mine." With this "I" and "mine," the question arises: does it exist in the way it appears? The way it appears causes problems. Buddhism teaches that there is no inherent entity existing from its own side, neither in external objects nor in our body or mind. Everything is characterized by dependent origination. That’s why the Buddha, 2,500 years ago, talked about the view of emptiness or ultimate reality – that everything is dependent and nothing exists from its own side. Not realizing this, the "I" and "mine" appear to exist inherently, which is why we get angry and develop attachment.

These findings are echoed in modern science, particularly in quantum mechanics. Physicists like David Bohm and Carlo Rovelli tell us that there is no concrete entity to be found anywhere. David Bohm once said that self-identity is a self-deceptive thought, just a convincing show, which is why people take it as an apparent reality. We believe it’s there, and that’s why we accept it. But if we analyze it, we cannot truly find a concrete "I" or "mine." Buddhist teachings explain how to eliminate this ignorance, which is the root of all forms of afflictions.

So, it’s possible to not only decrease our destructive emotions but to actually eliminate them entirely?

In the Abhidharma, a destructive emotion is called an affliction. An affliction is defined as that which disturbs the peace of mind. For example, anger disturbs your peace; you're not in control anymore, you are emotionally hijacked. But if you analyze the destructive emotions well, you will see that it's possible to eliminate them because destructive emotions are not an innate part of the mind. They're like clouds obscuring the blue sky. The clouds are not a part of the blue sky at all. Since destructive emotions are not an innate part of the mind, they can be removed.

The second point about disturbing emotions is that they are temporary. You know how you get triggered by reading a message, seeing a person, or hearing something? You get irritated, and that triggers the process of disturbing emotions. But if you play with causes and conditions, you can prevent that emotional hijack from coming into being.

The third point is that destructive emotions are not in accord with reality. We fabricate a mental image of a person or situation we dislike: "Oh, this person is bad because of this, because of that, because of this!" We create more faults in the mental image than the person actually has. The main problem is thinking that this mental image is the person. And then we create many problems. So, you see that destructive emotions are also not in accord with reality; they're just a mental fabrication.

By using reasoning, we can transform the entire process. That's why reasoning is very important in this aspect of the training.

And what about meditation? Does meditation play any role here?

In Buddhism, we have two types of meditation: concentration meditation, sometimes translated as placement meditation, and analytical meditation. Placement meditation helps us to concentrate the mind on a particular object, which is needed. We need to focus. You know when you read a book, and a few lines down, you think, "What did I just read?!" It's the same with meditation: if you don't have concentration, you're wasting your time.

Distraction is a waste of time. So, you need to concentrate, you need to develop placement meditation, concentration meditation. Eventually, if you accomplish samadhi, you can focus on the object according to your wish. The more focused you are, the more progress you make in your analytical meditation.

Even if you accomplish samadhi, even if you’re capable of staying on your object according to your wish, and it's a very pleasant and blissful state, you cannot stay in that state all the time. When you come out of that state, although your mind is much calmer and more aware, which are benefits, they don’t eliminate destructive emotions. For that purpose, we need analytical meditation.

Why do we need analytical meditation? Because our destructive emotions use logic. "I don't like this person because of this. Because of that." "I don't like this situation because of this, because of that." Although the reasons are not valid, the mind is capable of reasoning within a few split seconds and then believing it. That's what destructive emotions do.

Meditation in Tibetan is the term "gom," which means to habituate yourself to positive patterns. And that's exactly what happens in analytical meditation. It is only possible to transform destructive emotions like anger, attachment, ignorance, and to transform mental difficulties like anxiety, fear, depression, by the power of reasoning. If you do reasoning in a very structured, concentrated way– and that's why you need concentration meditation – then the transformation does happen over time. And then eventually, in order to cut ignorance, you have to realize ultimate reality.

Can you explain the concept of ultimate reality in Buddhism and how it differs from conventional reality? Why is understanding these two aspects crucial for overcoming suffering?

The ultimate nature of reality or the view of emptiness is very essential in Buddhism. Why is it so essential? Because it eliminates ignorance. Ignorance is the root of all forms of suffering; it's the root of all afflictions and destructive emotions. This ignorance, as I explained earlier, is a concept or mind that apprehends or holds on to an "I" and "mine" that exists independently, that exists from its own side, that exists inherently, that exists very solidly. But there is nothing that can exist in such a solid, independent way because everything is in the nature of dependence, right?

If you look in your body or in your mind, you cannot find anything as solid as the "I" appears. So, the "I" that appears as very solidly existing from its own side, inherently, is the particular "I" or self that is not there.

So, that particular self does not exist in the way it appears. It appears in a particular way, but it doesn't exist exactly as it appears – very concrete and existing from its own side. So that's why we say that we are empty of that self.

But there is a conventional body, a conventional mind, and a conventional imputation based on this mere collection of the body and mind. We say that I am Tenzin Namdak, right? That means there is something there, and we know that. We feel things and have experiences, so there is a body, a mind, and an experience.

But there's no solid entity, existing from its own side, or inherent "I" to be found. So, the distinction we should make is that there is no self that exists from its own side because everything is in the nature of dependent origination. But, on the conventional level, there is a mere kind of "I" or mere person or mere self that is just imputed or labeled or named upon the mere collection of the body and the mind.

And we see many things are just merely imputed. I'll give one very simple example. I went recently to a garden party with the Queen at Buckingham Palace with a friend of mine, and we came out of the gate, with a lot of people standing outside, tourists and people looking in. As we were coming out of the gate, they saw us, and they probably thought, "Oh, important persons!" I said to my friend, "Look, now they think we are important!" And then we passed the gate, and we were with the people together. And then I told my friend, "You see, now we are just normal people, right?"

So, you can see that at a particular time, people grasped onto, "Oh, this is an important person." But then you mix with the important person, and people don't notice you anymore, and you can see that it was all just merely imputed by the mind. It appears very concrete at that particular time, but it doesn't exist in that way. It's just a label.

Ultimate reality is very important in Buddhist doctrine, and conventional reality is also very important. The two truths help us to understand what exists and how things exist. His Holiness the Dalai Lama often indicates that the best way to proceed in Buddhism is to first start with the two truths, then the four noble truths, and then understanding refuge. And why is that so? Because if you study the two truths, you understand how ignorance creates an affliction, and how afflictions create particular activity or karma, and how that produces suffering. That's conventional reality. Then, ultimate reality comes into the picture. You see that destructive emotions can be eliminated by the correct understanding of reality. So, you understand, basically, the four noble truths: the truth of suffering, the cause of suffering, the true cessation, and the true paths.

In fact, you realize: “I can accomplish that. I can eliminate destructive emotions. I can realize ultimate reality.” And that is, for a Buddhist practitioner, the real refuge. The refuge in your own accomplishment of the abandonment of afflictions, your own accomplishment of the realization of ultimate reality or emptiness. And so that's kind of how you structure the two truths, the four noble truths, and going for refuge eventually.

For someone new to Buddhism who might feel overwhelmed by its depth and all the various schools and traditions, what practical advice do you have to help them begin their practice?

Buddhism is very profound; it’s detailed, with a lot of philosophy and a lot of psychology, and there are various traditions. We should see what we can study and put into practice. Initially, it’s good to examine the traditions well and come to a conclusion to study one particular tradition, get a good understanding of it, and then stick with that tradition for some time. After that, you can study some other things on the side.

For me, Buddhism was something where I could find all the answers, as it’s so rich in mind science and philosophy. Even when combined with modern scientific findings, there’s a lot of common ground. Mind science in Buddhism is similar to what we call Buddhist psychology. Buddhist mind sciences are extremely rich and extremely clear for understanding more about destructive emotions, how to deal with them, and how to actually achieve a more sustainable form of happiness. You gain knowledge from the scriptures and from the explanatory texts and teachings, and then you have to put it into practice by analyzing destructive emotions.

Does a destructive emotion like anger really produce a mind that is unhappy? Does it really produce a mind that is not clear? Does it really produce a mind that gets irritated so that you might verbally abuse a person? These are the aspects you have to analyze, and that’s what we call practice.

At the same time, we cannot live like Milarepa. We have to be realistic about how much we can study Buddhism and how much we want to put it into practice. The main purpose is to put it into practice because academic studies alone don’t bring benefits. That’s why it’s essential to use the teachings in our daily life, especially with the emotional aspects of our well-being.

Jamyang Buddhist Centre is renowned for its excellent philosophy courses, including medium and long-term programs. Can you provide an overview of the various courses that you offer here?

If you really want to gain a deep understanding of one particular tradition, it's important to invest your time. That’s why, at Jamyang, we started with the vision of offering long-term programs. We have a five-year, a three-year, and a two-year program with different levels of Buddhist philosophy and practice. You can see people change over time, which is very inspiring.

Especially now, with the hybrid system, people from various countries and locations around the globe can participate. These study programs are not only crucial for Buddhism’s preservation but also for individuals to gain a good understanding of the Buddhist path and practice it.

We offer a five-year program called the Basic Program, though it’s not basic. We cover the Middle Length Lam-rim by Tsongkhapa, the Bodhisattvacharyavatara by Shantideva, and delve into aspects of traditional philosophy, such as tenet systems, as well as psychology, the mind, and mental factors.

This is how we present the Buddhist teachings in the West. We work with weekend courses, meaning one weekend a month. In the monastic system, we have six days a week for study. So, you can imagine the depth of the studies differs. We adjust these programs because no one here can dedicate 20 years full-time. We summarize the essential, important points for transforming the mind.

We also include some secular elements in programs like Exploring Buddhism, which are designed to be more accessible to those new to Buddhism and include aspects of science.

I was advised by my own teacher to take it easy, because if you have a vast plan and you have this incredibly vast vision, then you know you're not going to change your mind overnight. It's going to take time, especially when you think about realizations. And then you think that it's not only this life, you think you'll do this for a few lifetimes, and then things will happen. So that vision is very important to cut down this short-sighted aspect we all walk around with.

And then, if you have this vast vision within Buddhism, you get this idea that you don't have to rush and you don't have to push yourself too much. You take it easy, but you continue.

So, you make sure you make plans according to this vast vision, and then you do it in a structured way where you can believe the results of it by seeing these incredible beings. And that becomes a very enjoyable way of studying and practicing!

Thank you, Geshe Namdak, for condensing your decades of intense studying into such relatable nuggets of wisdom for us all!