Introduction

[As background, see: The Two Truths: Vaibhashika and Sautrantika]

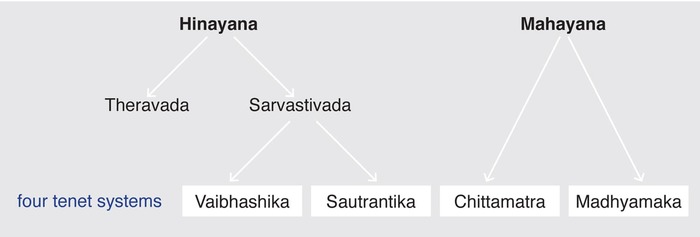

The Tibetans study four tenet systems (grub-mtha’) of Indian Buddhism. Among them, Vaibhashika (bye-brag smra-ba) and Sautrantika (mdo-sde-pa) are Hinayana systems – specifically, subdivisions of the Sarvastivada (thams-cad yod-par smra-ba) school of Hinayana, and not Theravada. Chittamatra (sems-tsam-pa) and Madhyamaka (dbu-ma-pa) are Mahayana.

Each of the four Tibetan traditions presents each of the four tenet systems differently. Here, we shall outline the basic features of the Gelug presentation of the Chittamatra system. To represent this position, we shall rely primarily on the explanations that accord with the textbook tradition of the sixteenth-century master Jetsun Chokyi Gyaltsen (rJe-btsun Chos-kyi rgyal-mtshan), followed by Ganden Jangtse (dGa’-ldan Byang-rtse) and Sera Je (Se-ra Byes) Monasteries. We shall occasionally supplement these with explanations given by Kunkyen Jamyang Zhepa (‘Jam-dbyangs bzhad-pa Ngag-dbang brtson-’grus).

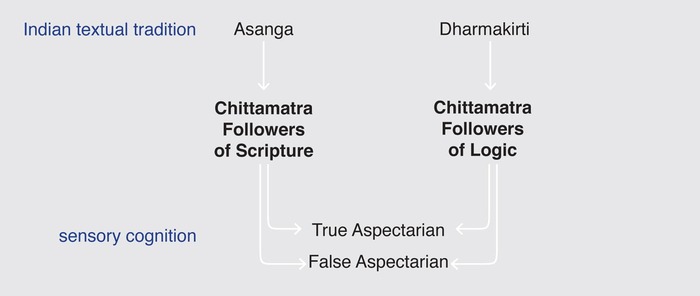

There are two main ways of specifying subdivisions within Gelug Chittamatra.

One division scheme derives from the Indian sources that are followed:

- Chittamatra Followers of Scripture (lung-gi rjes-’brang-gi sems-tsam-pa) follow the Indian textual tradition of Asanga.

- Chittamatra Followers of Logic (rigs-pa’i rjes-’brang-gi sems-tsam-pa) follow the Indian textual tradition of Dharmakirti.

The second division derives from a difference in explanation of sensory cognition:

- True Aspectarian (rnam bden-pa),

- False Aspectarian (rnam brdzun-pa).

The two division schemes overlap. Thus, some Chittamatra Followers of Scripture are True Aspectarians and some are False Aspectarians. The same is the case among Chittamatra Followers of Logic. We shall try to explain the general assertions common to all divisions of Chittamatra, and point out only some of the major differences among the subdivisions.

The two division schemes, together with the three subdivisions of the True Aspectarian division, which will be discussed later in this essay, are also found in Sautrantika.

The Meaning of “Mind-Only”

According to the Chittamatra (Mind-Only) school, the only way the existence or nonexistence of anything can be established is exclusively in terms of its relation to mind (sems). Mind, in Buddhism, refers to the mental activity of merely giving rise (shar-ba) to a cognitive object and, simultaneously, cognitively engaging (‘jug-pa) with it; and not to the instrument that does the cognizing. The former aspect of this activity is called “clarity” (gsal) and the latter “awareness” (rig). “Merely” (tsam) refers to the fact that this activity occurs without there being an independently existing, separate “me” that is actively making this activity happen, or passively observing it.

Thus, everything has an identity-nature established in terms of mind (sems-kyi bdag-nyid) and everything is an aspect of mind (sems-kyi rnam-pa). In the most general terms, this means that everything that exists or does not exist is either a cognitive object (yul, object of cognition) or both a cognitive object and something that cognizes an object (yul-can). It also means that the manner in which any object exists can only be established within the context of the cognition of that object.

An existent phenomenon (yod-pa) is something established as a validly knowable object (tshad-mar grub-pa), or something established as a foundation for valid cognition (gzhi-grub).

A nonexistent phenomenon (med-pa), such as a unicorn or an impossible way of existing, may be cognized, but not validly. It is the involved object (‘jug-yul) cognized by distorted cognition (log-shes). An involved object is the main object that a particular cognition cognitively engages. Thus, whether something is an existent phenomenon or a nonexistent one can only be established in terms of the validity or invalidity of the mind that cognizes it.

[See: The Appearance and Cognition of Nonexistent Phenomena]

Mind-only, or “aspect-of-mind only” (rnam-par rig-pa tsam, Skt. prajnapti), then, does not mean that everything is a way of being aware of something (shes-pa), or that everything exists only in our minds and that no other beings actually exist. If that were the case, compassion for others would be pointless. Mind-only is not a solipsistic view of reality.

Types of Existent Phenomena

An existent phenomenon may be either nonstatic (mi-rtag-pa, impermanent) or static (rtag-pa, permanent), depending on whether or not it is affected by causes and conditions and, thus, whether or not it changes from moment to moment. This is the case regardless of the length of time that a nonstatic or static phenomenon exists.

A nonstatic phenomenon may be either:

- a form of physical phenomena (gzugs),

- a way of being aware of something (shes-pa), or

- a nonstatic abstraction (ldan-min ‘du-byed, non-congruent affecting variable), such as time or a person (gang-zag).

Static phenomena include:

- audio categories (sgra-spyi, audio universals, sound universals) and meaning/object categories (don-spyi, meaning universals),

- spaces (nam-mkha’) – absences of obstructive contact (the absence of any material object that could be contacted in a location and that would obstruct something being there),

- voidnesses (stong-pa-nyid, Skt. śūnyatā, emptiness, absence of impossible ways of existing),

- lack of impossible souls (bdag-med, selflessness, identitylessness).

Three Types of Characterized Phenomena

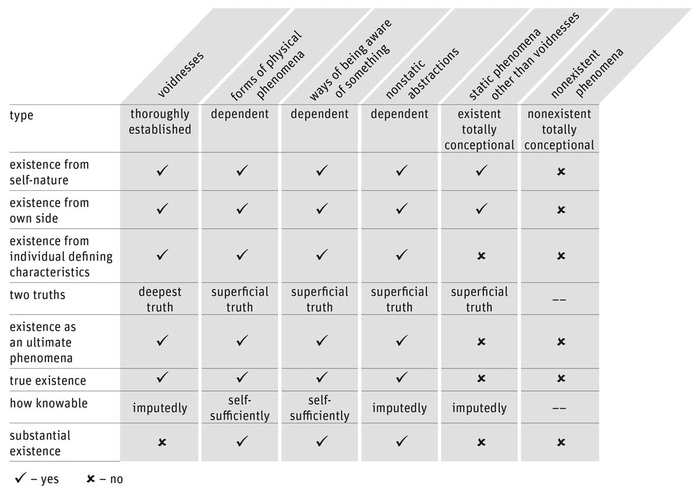

Existent and nonexistent phenomena are divided among the three types of characterized phenomena (mtshan-nyid gsum, Skt. trilakshana):

- phenomena characterized as totally conceptional (kun-brtags-pa’i mtshan-nyid, Skt. parikalpita-lakshana, imaginary objects),

- phenomena characterized as dependent (gzhan-dbang-gi mtshan-nyid, Skt. paratantra-lakshana, other-powered phenomena, relative phenomena),

- phenomena characterized as thoroughly established (yongs-su grub-pa’i mtshan-nyid, Skt. parinishpanna-lakshana, perfect objects).

The three types are called “characterized phenomena” because each of them has its own specific defining characteristics (mtshan-nyid, Skt. lakshana). Let us call them for short “totally conceptional phenomena” (kun-brtags), “dependent phenomena” (gzhan-dbang), and “thoroughly established phenomena” (tongs-grub).

Totally Conceptional Phenomena

Totally conceptional phenomena are defined as phenomena not established as ultimate phenomena (don-dam-par ma-grub-pa), but nevertheless established as having the essential nature of the conceptual cognitions of them (rang-’dzin rtog-pa’i ngo-bor grub-pa).

There are two types of totally conceptional objects:

- Existent totally conceptional objects (yod-pa’i kun-brtags) – namely, all static phenomena other than voidnesses, such as categories and spaces. These are also called “denumerable totally conceptional objects” (rnam-grangs-pa’i kun-brtags), because they are denumerable among validly knowable objects – in other words, they may be counted among objects that can be validly cognized.

- Nonexistent totally conceptional objects (med-pa’i kun-brtags), such as unicorns and impossible ways of existing. These are also called “totally conceptional objects fully cut off from being definitional ones” (mtshan-nyid yongs-su chad-pa’i kun-brtags).

Dependent Phenomena

Dependent phenomena (gzhan-dbang, Skt. paratantra, other-powered phenomena) are those that arise dependently on the power of other phenomena as their causes and conditions. Thus, they encompass all nonstatic phenomena.

Dependent phenomena are defined as the affected phenomena (‘dus-byas, compounded phenomena) – meaning the phenomena affected by causes and conditions – that are the objects of conceptual cognition (rnam-par rtog-pa’i spyod-yul) and the locus (gnas, abode) – in other words, the bases of imputation (gdags-gzhi) – for totally conceptional phenomena, both existent and nonexistent ones.

- Dependent phenomena are the involved objects of conceptual cognition and are what appear (snang-ba) in those cognitions. Although existent totally conceptional objects are the appearing objects (snang-yul) of conceptual cognitions, imputed on these dependent phenomena, they do not actually appear, since they do not have any form.

There are two varieties of dependent phenomena – purified (dag-pa) and unpurified (ma-dag-pa) – each of which includes all three types of nonstatic phenomena: forms of physical phenomena, ways of being aware of something, and nonstatic abstractions.

- Purified dependent phenomena (dag-pa’i gzhan-dbang) do not perpetuate samsara. These include, for example, the various types of non-conceptual deep awareness (rtog-pa med-pa’i ye-shes) – such as the subsequently attained deep awareness of an arya (‘phags-pa’i rjes-thob ye-shes, the wisdom of an arya’s post-meditation period) – as well as the physical features of a Buddha’s corpus of forms (gzugs-sku, Skt. rupakaya, Form Body).

- Unpurified dependent phenomena (ma-dag-pa’i gzhan-dbang) perpetuate samsara. These include the obtainer aggregates (nyer-len-gyi phung-po) of samsaric beings – namely, the aggregate factors that derive from unawareness (ignorance) of voidness, that are mixed with that unawareness, and that perpetuate that unawareness.

Among forms of physical phenomena, Gelug includes both sensibilia (sense data) – moments of colored shapes, sounds, smells, tastes, and physical sensations – and commonsense objects (‘jig-rten-la grags-pa), such as tables and oranges, which pervade the sensibilia of several sense faculties and endure over time.

Thoroughly Established Phenomena

Thoroughly established phenomena include both types of lack of impossible “soul” (bdag-med, identitylessness, selflessness). These lacks of impossible souls – in other words, these voidnesses (emptinesses) or absences of impossible ways of existing – are static phenomena, but not totally conceptional ones. The two types of lack are:

- The lack of an impossible soul of a person (gang-zag-gi bdag-med, identitylessness of a person, selflessness of a person),

- The lack of an impossible soul of phenomena (chos-kyi bdag-med, identitylessness of all phenomena, selflessness of all phenomena).

The lack of an impossible soul of a person encompasses two levels of impossible soul that a conventionally existing person is devoid of existing as:

- The coarse lack of an impossible soul of a person (bdag-med rags-pa) is a person’s absence (voidness) of having existence established as a static, monolithic entity, independent from the aggregates on which it is imputed (rtag-cig rang-dbang-can-gyis grub-pa).

- The subtle lack of an impossible soul of a person (bdag-med phra-mo) is a person’s absence of having existence established substantially as a self-sufficiently knowable phenomenon (rang-rkya thub-pa’i rdzas-yod-kyis grub-pa, existence established as a self-sufficiently knowable phenomenon).

Regarding the lack of an impossible soul of phenomena, Chittamatra does not present a coarse level. The subtle level has two points:

- The absence of forms of physical phenomena, and the valid cognitions that take these forms of physical phenomena as their cognitive objects, deriving from different natal sources (gzugs-dang gzugs-’dzin-pa’i tshad-ma rdzas-gzhan-gyis stong-pa). In other words, the absence of forms of physical phenomena existing in the manner of external phenomena (phyi-don).

- The absence of forms of physical phenomena having existence established by individual defining characteristic marks as foundations on which affix the sound of the words “forms of physical phenomena” (gzugs gzugs-zhes-pa’i sgra rang-gi ‘jog-gzhir rang-gi mtshan-nyid-kyis grub-pas stong-pa). In addition, the absence of forms of physical phenomena having existence established by individual defining characteristic marks as foundations on which cling the conceptual cognitions that take these forms of physical phenomena as their cognitive objects (gzugs gzugs-’dzin-pa’i rtog-pa’i zhen-gzhir rang-gi mtshan-nyid-kyis grub-pas stong-pa). This last absence is sometimes counted as a third type of lack of impossible soul of phenomena.

The above thoroughly established phenomena are called “thoroughly established phenomena that are objects of cognition” (yul-gyi yongs-grub). They will be discussed in more detail later in this essay.

There are also “acquired thoroughly established phenomena” (thob-pa’i yongs-grub), namely all true stoppings (‘gog-bden, true cessations) and all nirvanas (myang-’das). Both thoroughly established phenomena that are objects of cognition and those that are aquired constitute “unchanging thoroughly established phenomena” (‘gyur-med yongs-grub). All of them are static phenomena, and static phenomena do not change.

There are also “thoroughly established phenomena that actualize” (sgrub-pa’i yongs-grub), such as the deep awareness of an arya’s total absorption on voidness (‘phags-pa’i mnyam-bzhag ye-shes, the wisdom of an arya’s meditative equipoise). They are the ways of being aware of something that bring about or “actualize” the previous two types of thoroughly established phenomena. They are also called “non-contradictory thoroughly established phenomena” (phyin-ci ma-log-pa’i yongs-grub), because these deep awarenesses non-conceptually cognize in a manner that does not contradict the actual way in which things exist. Although such phenomena are included among thoroughly established ones, they are not actually thoroughly established phenomena. Thoroughly established phenomena are unaffected phenomena (‘dus-ma-byas, uncompounded) – phenomena unaffected by causes and conditions: in other words, static phenomena.

External Phenomena

An external phenomenon (phyi-don) is a knowable object that comes from a natal source (rdzas) that is different from the natal source of the valid cognition of that knowable object. A natal source of something is that from which something arises, such as a seed for a plant, a womb for a baby, or an oven for a loaf of bread. The natal source that gives rise to the valid cognition of a knowable object is the karmic tendency (sa-bon, karmic seed) on the mental continuum of the person that experiences that valid cognition. More specifically, the natal source is a karmic tendency imputed on the alayavijnana (kun-gzhi rnam-shes, all-encompassing foundation consciousness, storehouse consciousness) of the person.

External phenomena arise from a natal source that is different from the karmic tendency that gives rise to the cognition of that phenomenon. Thus, external phenomena exist before the cognitions of them, acting as the focal objects (dmigs-yul) of those cognitions. In other words, they exist beforehand, outside the context of cognition of them. Awareness meets them and then cognizes them.

Chittamatra asserts that external phenomena are nonexistent totally conceptional objects.

Existence Established by Something’s Self-Nature and Existence Established from Something’s Own Side

Chittamatra defines the various ways of existing in its own special manner, as is the case with the other Indian Buddhist tenet systems.

Existence established by something’s self-nature (rang-bzhin-gyis grub-pa, findably established existence, self-established existence, inherent existence) and existence established from something’s own side (rang-ngos-nas grub-pa) are synonymous terms (don-gcig). If a phenomenon has one of the two types of existence, it also has the other, and vice versa. Both modes of existence are defined as existence established by the fact that when one searches for the referent “thing” (btags-don), the actual “thing” referred to by a name or concept, corresponding to the names or concepts for something, that referent “thing” is findable. The referent “thing” is findable on the side of the object.

The findability of a referent “thing” on the side of an object of cognition does not imply, however, that the referent “thing” is found as an external object. It merely means that the referent “thing” is findable on the side of the object within the context of the valid cognition of that object.

All existent phenomena – namely, all validly knowable phenomena – have their existence established by their self-natures and their existence established from their own sides. In other words, if something is validly knowable, for example a table, its existence as a validly knowable object is established by the fact that the “thing” that corresponds to the name or concept of “a table” – namely, a table – is findable on the side of the cognized table.

Further, something being findable does not imply something being visible or even physical. It means something being findable by a mind that is scrutinizing superficial truths (kun-rdzob bden-pa, conventional truths, relative truths) or deepest truths (don-dam bden-pa, ultimate truths). In other words, the referent “thing” that the name or concept for something corresponds to is able to withstand such scrutiny and does not fall apart. The referent “thing” remains as a validly knowable phenomenon to the mind that is scrutinizing it.

Nonexistent totally conceptional phenomena do not have existence established by their self-natures or existence from their own sides. When one searches for the referent “thing” that corresponds to the name or concept “unicorn” or to the name or concept “an impossible way of existing,” one cannot find the corresponding referent “thing.”

Existence Established by Something’s Individual Defining Characteristic Marks

Among phenomena having their existence established by their self-natures – in other words, among validly knowable phenomena – some also have their existence established by their individual defining characteristic marks (rang-gi mtshan-nyid-kyis grub-pa) and some have their existence not also established by their individual defining characteristic marks (rang-gi mtshan-nyid-kyis ma-grub-pa).

The definitions of these two modes of existence are rather complex. An object of cognition has its existence established by its individual defining characteristic marks if its existence is established from the side of its own unshared way of abiding (mthun-mong ma-yin-pa’i sdod-lugs) as a cognitive object that is not merely imputable by a conceptual cognition. An object of cognition has its existence not established by its individual defining characteristic marks if its existence is not established from the side of its own unshared way of abiding as a cognitive object that is not merely imputable by a conceptual cognition.

Let us examine these definitions. Although the referent “things” corresponding to the names or concepts of all validly knowable objects are findable on the sides of those validly knowable objects, not all validly knowable objects have an unshared manner of abiding on their own sides that has the power to establish them as validly knowable objects. The dividing line is whether or not these objects are merely imputable by valid conceptual cognitions of them.

- The unshared manner of abiding referred to here in the definition is abiding (or existing) with an individual defining characteristic mark (rang-gi mtshan-nyid, Skt. svalakshana) findable on the object’s own side.

- The individual defining characteristic mark referred to here is one that is on the side of an object and which defines or delineates that object as an individual, specific object of cognition. Another way of rendering the technical term for it would be “a characteristic mark defining the individuality of something.” As a gross approximation to help make “an individual defining characteristic mark” more understandable, it can be understood as analogous to a solid line or plastic casing findable around a knowable object and which has the power to delineate the individuality of that object as an individual item that can be cognized.

In general, all knowable objects – whether validly knowable or not – have individual defining characteristic marks; otherwise, they would not be individual objects of cognition. They would all be the same, identical object of cognition. The issue here is whether or not validly knowable objects have the type of individual defining characteristic marks on their own sides that have the power to establish the existence of these validly knowable objects that are characterized by them. Remember, of course, that this is within the context of the objects being validly cognized.

- If a validly knowable object is merely imputable by a valid conceptual cognition of it, then the existence of this validly knowable object is not established by its individual defining characteristic mark.

- If a validly knowable object is not merely imputable by a valid conceptual cognition of it, then the existence of this validly knowable object is established by its individual defining characteristic mark.

The crucial word here is “merely.” If a validly knowable object is imputable by a valid conceptual cognition of it, but not “merely imputable,” then, according to the Chittamatra assertion, its existence is still established by its individual defining characteristic mark.

The basic issue, then, of individual defining characteristic marks in this context concerns whether or not, in the context of a conceptual cognition of a dependent phenomenon, the individual defining characteristic mark of that conceptually implied dependent phenomenon, on which a word (ming) or a label (brda) or an audio category (sgra-spyi) or meaning/object category (don-spyi) is set has the power all by itself to establish the existence of that dependent phenomenon as belonging to that category or being the meaning of that word or label. The subtle voidness of all phenomena is that such characteristic marks are imputed onto the object together with the word, label or category. They are not findable on the side of the object outside of that context.

- A name is a combination of sounds that are assigned a meaning (don).

- A label is a name applied to the knowable objects that the name signifies – whether or not those objects are validly knowable. Unicorns and impossible manners of existence, after all, although nonexistent, have the names and labels “unicorn” and “impossible modes of existence.”

The defining characteristic mark that establishes the existence of something as an individual validly knowable object, however, is found on the side of all validly knowable phenomena, whether or not the phenomenon is imputed on a basis. The issue here is whether the existence of an object is established merely by the power of that defining characteristic mark on the side of the object, or is the existence of an object established by the power of that mark only in the context of the object being imputed on a basis. In the former case, the object has existence established by its individual defining characteristic mark, and in the latter case it lacks such a manner of establishing its existence. Thus,

All dependent phenomena (all nonstatic phenomena) and all thoroughly established phenomena (all voidnesses) have their existence established by their individual defining characteristic marks. This is because they are not merely imputable by the valid conceptual cognitions of them. They can be validly cognized non-conceptually.

All totally conceptional phenomena (all static phenomena other than voidnesses, as well as all nonexistent phenomena) have their existence not established by their individual defining characteristic marks. This is because they are merely imputable by the valid conceptual cognitions of them.

The sets of phenomena having their existence established by their self-natures and phenomena having their existence established by their individual defining characteristic marks constitute a trilemma (mu-gsum). In other words, there are three possibilities:

- Things can have both manners of existence, such as all dependent phenomena and all thoroughly established phenomena.

- Things can have their existence just established by their self-natures, but not have their existence established by their individual defining characteristic marks, such as all existent totally conceptional phenomena.

- Things can have neither manner of existence, such as nonexistent totally conceptional phenomena.

- There is no fourth possibility. There is nothing that has its existence established by its individual defining characteristic marks that does not also have its existence established by its self-nature.

Deepest and Superficial Truths

Deepest truths (don-dam bden-pa, ultimate truths) are those phenomena that are findable by a valid cognition scrutinizing (dpyod-byed, analyzing) what is deepest (don-dam-pa, ultimate). Only thoroughly established phenomena are deepest truths.

Superficial truths (kun-rdzob bden-pa, relative truths, conventional truths) are those phenomena that are findable by a valid cognition scrutinizing what is conventional (tha-snyad, Skt. vyavahara). Dependent and existent totally conceptional phenomena are superficial truths.

Deepest truths and superficial truths share the same essential nature (ngo-bo gcig). In other words, they are the same essential phenomenon, but merely scrutinized from two different points of view. When analyzed from the point of view of convention, one finds a superficial truth – something is a dependent phenomenon or a totally conceptional phenomenon. When analyzed from the point of view of deepest truth, one finds a deepest truth – it is devoid of existing in an impossible manner, namely with an impossible soul. That deepest truth is a thoroughly established phenomenon.

Truly Established Existence and Existence Established as an Ultimate Phenomenon

Among phenomena having their existence established by their self-natures, some have truly established existence (bden-par grub-pa, true existence) and some have not truly established existence (bden-par ma-grub-pa, non-true existence).

An object of cognition has truly established existence if its existence is established as an ultimate phenomenon (don-dam-par grub-pa). An object of cognition has not truly established existence if its existence is not established as an ultimate phenomenon (don-dam-par ma-grub-pa).

All dependent phenomena and thoroughly established phenomena – in other words, all nonstatic phenomena and all voidnesses – have truly established existence. This is because both types of phenomena are ultimate phenomena. All totally conceptional phenomena – all static phenomena other than voidnesses, as well as all nonexistent phenomena – have not truly established existence. This is because they are all non-ultimate phenomena.

Thus, the sets of ultimate phenomena and deepest truths constitute a trilemma:

- Things can be both ultimate phenomena and deepest truths – for example, thoroughly established phenomena.

- Things can be ultimate phenomena, but not deepest truths – for example, dependent phenomena.

- Things can be neither ultimate phenomena nor deepest truths – for example, totally conceptional phenomena.

- Nothing, however, can be a deepest truth without also being an ultimate phenomenon.

There are two ways of specifying which existent phenomena are ultimate phenomena:

- Those with existence established by their individual defining characteristic marks.

- Those that appear to an arya’s total absorption (‘phags-pa’i mnyam-bzhag).

Both dependent phenomena and thoroughly established phenomena have ultimate existence and thus have truly established existence, because both have existence established by their individual defining characteristic marks. Both also appear to an arya’s total absorption, but not simultaneously.

An Arya’s Total Absorption

Total absorption is a state of mind having the joined pair (zung-’brel) of shamatha (zhi-gnas, a stilled and settled state of mind, mental quiescence, calm abiding) and vipashyana (lhag-mthong, an exceptionally perceptive state of mind, special insight), and in which absorbed concentration (ting-nge-’dzin, Skt. samādhi) is focused single-pointedly on the lack of an impossible soul of either a person, phenomena, or both.

- The total absorption of an applying pathway mind (sbyor-lam, path of preparation) is conceptual.

- The total absorptions of a seeing pathway mind (mthong-lam, path of seeing) and an accustoming pathway mind (sgom-lam, path of meditation) are non-conceptual and are the total absorptions of an arya.

[See: Shamatha and Vipashyana: General Presentation]

An arya’s total absorption rids an arya of various levels and degrees of obscuration (sgrib) concerning each of the four noble truths – true sufferings, true causes of suffering, true stoppings (true cessations), and true pathway minds (true paths). In the case of bodhisattva aryas, up through the seventh bhumi-mind, the total absorption gets rid of both emotional obscurations (nyon-sgrib) preventing liberation and cognitive obscurations (shes-sgrib) preventing the omniscience of a Buddha. The eighth through tenth bhumi minds get rid of only cognitive obscurations, but those cognitive obscurations still include the habits of the emotional obscurations.

- Unawareness (ma-rig-pa, ignorance) of the coarse and subtle lacks of impossible soul of a person, and the disturbing emotions and attitudes (nyon-mongs, “afflictive emotions”) that derive from them, as well as the tendencies (sa-bon, seeds) of these unawarenesses and disturbing emotions and attitudes, constitute the emotional obscurations.

- Unawareness of the two types of subtle lack of impossible souls of phenomena, as well as their habits (bag-chags), constitute the cognitive obscurations.

[See: The Five Paths]

Each phase of an arya’s total absorption has several steps. Let us consider, for example, each phase of the total absorption of a bodhisattva arya’s seeing pathway mind. Each phase gets rid of a portion of the obscurations concerning one of the four noble truths.

- First, one focuses on the superficial truth of one of the noble truths.

- Then, one scrutinizes (analyzes), with a mind scrutinizing deepest truths, whether the noble truth has an impossible soul of a person on whose mental continuum the noble truth occurs. In other words, one doesn’t scrutinize whether the noble truth itself exists as an impossible soul of a person, one scrutinizes whether the person on whose mental continuum the noble truth occurs exists has an impossible soul of a person. One also scrutinizes whether or not the noble truth itself exists with an impossible soul of phenomena.

- After decisively cognizing that the noble truth lacks such impossible souls, because these impossible souls are nonexistent, one focuses on the deepest truth of the noble truth – namely, on the lack of an impossible soul of a person concerning this noble truth and also on the lack of an impossible soul of phenomena concerning this noble truth. This step has two parts:

- The uninterrupted pathway mind (bar-chad-med lam), which is the mind that gets rid of the portion of the obscurations to be gotten rid of at this step.

- The liberated pathway mind (rnam-grol lam), which is the mind that is rid of the portion of the obscurations to be gotten rid of at this step.

Thus, despite the fact that total absorption is an absorbed concentration on a lack of an impossible soul, the total absorption of an arya can be divided into:

- An arya’s total absorption on the superficial truths of each of the four noble truths.

- An arya’s total absorption on the deepest truths of each of the four noble truths.

During an arya’s total absorption on the superficial truths of the four noble truths, only dependent phenomena appear and are explicitly apprehended (dngos-su rtogs-pa). During an arya’s total absorption on the deepest truths of the four noble truths, only thoroughly established phenomena appear and are explicitly apprehended. Thus, both dependent phenomena and thoroughly established phenomena are ultimate phenomena and have truly established existence. Moreover, both dependent phenomena and thoroughly established phenomena are ultimate phenomena also because both have existence established by their individual defining characteristic marks.

- Third noble truths, true stoppings, are thoroughly established phenomena. The locus for them is the mental continuum of an arya on which they occur. During an arya’s total absorption on the superficial truth of third noble truths, only the locus of the true stoppings appears and is explicitly apprehended. The true stoppings imputed on that locus and scrutinized do not actually appear and thus are only implicitly apprehended (shugs-la rtogs-pa).

Imputably Knowable Phenomena

Imputedly knowable phenomena (btags-yod) are defined as those validly knowable phenomena which, in order to actually be taken as cognitive objects (dngos-bzung), require their actually being cognitively taken from reliance (rten-pa) on another object.

For something knowable “actually be taken as a cognitive object” it needs to be either explicitly apprehended or implicitly apprehended. A knowable object is apprehended if it is cognized both accurately and decisively by the cognition that takes it as its involved object (‘jug-yul).

- Cognitive objects may be apprehended by valid bare cognition (mngon-sum tshad-ma), valid inferential cognition (rjes-dpag tshad-ma), or subsequent cognition (bcad-shes) of either of the previous two. Bare cognition and inferential cognition are valid cognitions (tshad-ma) – defined as fresh (gsar), non-fallacious (mi-bslu-ba) cognitions of an object. Subsequent cognition is not a valid means of cognition, because it is not fresh. Bare cognition is always non-conceptual; inferential cognition is always conceptual.

- If a knowable object is apprehended explicitly, a mental aspect (rnam-pa) of the object arises (appears) in the cognition. For example, in bare sensory cognition of a vase, a mental aspect representing the vase appears and one explicitly apprehends it.

- If a knowable object is apprehended implicitly, a mental aspect representing the object does not arise (appear) in the cognition. For example, in bare auditory cognition of the words “a person dies and is reborn,” although a mental aspect representing the existence of past and future lives does not appear, one implicitly apprehends their existence with hearing these words.

[See: Apprehension of Validly Knowable Phenomena]

Imputedly knowable phenomena include:

- Among dependent phenomena, only nonstatic abstractions.

- Among totally conceptional objects, only existent ones. Nonexistent totally conceptional objects are not validly knowable and therefore cannot be apprehended explicitly or implicitly.

- All thoroughly established phenomena.

Moreover,

- Nonstatic abstractions and thoroughly established phenomena may be apprehended either conceptually or non-conceptually.

- Existent totally conceptional phenomena occur only in conceptual cognition, where they are the appearing objects (snang-yul). They are not what cognitively appears (snang) in the cognition, because they cannot actually appear to mental consciousness, even through a mental aspect representing them. They are not apprehended by the conceptual cognition themselves, but are nevertheless apprehended within the context of the conceptual cognition in which they occur. The existent totally conceptional phenomena in a conceptual cognition are apprehended by the reflexive awareness (rang-rig) that accompanies the conceptual cognition. The reflexive awareness apprehends them nonconceptually, but only implicitly, because a mental aspect of them does not actually appear. Reflexive awareness will be discussed in part two of this essay.

The phrase “reliance on another object” in the definition means that during the first step of the cognition, the basis for imputation of the imputedly known phenomenon is apprehended by itself. Only by relying on that prior apprehension does the apprehension of the imputedly known phenomenon occur during a subsequent step.

In the case of apprehending a nonstatic abstraction or an existent totally conceptional phenomenon, during the final step both the basis for imputation and the imputedly cognized phenomenon are apprehended simultaneously.

- In the case of nonstatic abstractions, the apprehension requires two steps. Consider the example of valid cognition of a person, either conceptually or non-conceptually. (1) During the first step, one explicitly apprehends the aggregate factors, such as the body, that serve as the basis for imputation of a person. (2) During the second step, one simultaneously apprehends, explicitly, both the body and the person imputed on the body.

- In the case of existent totally conceptional phenomena other than space, the apprehension requires three steps. Consider the example of valid conceptual cognition of the meaning/object category (don-spyi) table, as when seeing an object with the physical features of a flat top supported by legs and thinking of it as a “table.” (1) During the first step, with non-conceptual visual bare cognition, one explicitly apprehends an object with a flat top supported by legs. (2) The second step is a series of steps that are too complex to be discussed in this essay, but involve the cognition of the name or label table. (3) During the final phase, in the context of a conceptual cognition, mental consciousness explicitly apprehends the physical object, while reflexive awareness simultaneously implicitly apprehends, non-conceptually, the meaning/object category table. The name or label table is imputed on the meaning/object category table and the meaning/object category table is imputed on the object with physical features that actually appears in the thought.

- In the case of the existent totally conceptional phenomenon space, the apprehension also requires three steps. (1) During the first step, a cow, for instance, explicitly apprehends with non-conceptual visual bare cognition, an “in-between area” (bar-nang), such as the area in between the two sides of an open doorway in the barn. (2) During the second step, with conceptual cognition, the cow’s mental consciousness cognizes the in-between area through the medium of the concept (rtog-pa) space, imputed on the in-between area. The conceptual cognition explicitly apprehends the in-between area and the reflexive awareness that accompanies that conceptual cognition implicitly apprehends, non-conceptually, the space there. (3) During the third step, while still conceptually cognizing the space imputably knowable on the basis of the in-between area, the cow, with non-conceptual visual cognition, explicitly cognizes the in-between area. In this manner, the cow explicitly apprehends the in-between area non-conceptually while simultaneously implicitly apprehending the space conceptually (i.e., within the context of a conceptual cognition). Thus, the cow knows that she can walk through the open door. In this case, the imputation occurs without the need for reliance on a name or a label. The cow did not need to learn the name or label “space” in order to be able to walk successfully through an open doorway.

In the case of apprehending a thoroughly established phenomenon non-conceptually, during the final step the basis for imputation does not need to be apprehended any longer. The imputedly known lack of an impossible soul may be explicitly apprehended by itself, with valid bare yogic cognition (rnal-‘byor mngon-sum tshad-ma). Bare yogic cognition is a valid non-conceptual cognition that arises from the dominating condition (bdag-rkyen) of a state of combined shamatha (zhi-gnas, a stilled and settled state of mind) and vipashyana (lhag-mthong, an exceptionally perceptive state of mind). Although it occurs with mental consciousness, it does not arise, in the manner of mental consciousness, from the dominating condition of mental sensors (yid-kyi dbang-po).

- Consider an arya’s total absorption on the voidness of a body having a different natal source from the valid cognition that takes the body as its cognitive object. A body is an example of the first noble truth, true suffering. (1) During the first step, with bare visual cognition, one explicitly apprehends the physical form of a body, non-conceptually. Imputable on the body is its existence established as having a singular natal source common to both the body and the valid cognition of the body. Imputable on that manner of existence is the nonexistent totally conceptional phenomenon: existence established as having a different natal source from the natal source of the valid cognition of the body. Existence established as having a singular common natal source is not apprehended, since it is totally obscured by the deceptive appearance of existence established as having a different natal source. Existence established as having a different natal source is also not apprehended, because it is a nonexistent totally conceptional phenomenon. (2) During the second step, one scrutinizes existence established as having a different natal source and decisively concludes that it is a nonexistent totally conceptional phenomenon. (3) During the final step, simultaneously with decisively cutting off the imputation of this nonexistent totally conceptional phenomenon, one explicitly apprehends, with non-conceptual bare yogic cognition, the thoroughly established phenomenon: the absence of existence established as having a different natal source. One does not apprehend at all, either explicitly or implicitly, the physical form of the body, which is the basis for this voidness (stong-gzhi). The non-conceptual bare yogic cognition implicitly apprehends existence established as having a singular common natal source, but one does not apprehend at all the singular natal source itself – the karmic tendency (sa-bon, seed) – that the body shares in common with the valid cognition of the body.

- Because of this difference between thoroughly established static phenomena and totally conceptional static phenomena, Chittamatra asserts that during an arya’s total absorption on deepest truths, only deepest truths appear and are explicitly apprehended. Because Sautrantika defines imputedly knowable phenomena differently, it asserts that during an arya’s total absorption on a lack of an impossible soul, the basis for imputation of this lack must appear and be explicitly apprehended by the non-conceptual yogic bare cognition, while the lack of an impossible soul is simultaneously implicitly apprehended, non-conceptually, by the reflexive awareness that accompanies the yogic bare cognition.

Self-sufficiently Knowable Phenomena

Self-sufficiently knowable phenomena (rdzas-yod, substantially and self-sufficiently knowable phenomena) are defined as functional phenomena (dngos-po) able to stand here (tshur-thub gyi dngos-po), or functional phenomena having existence established as something able to stand here (tshur-thub grub-pa’i dngos-po), or functional phenomena able to stand in their own place (tshugs-thub-gyi dngos-po). The three terms are synonymous.

A functional phenomenon is a nonstatic phenomenon. It is functional in the sense that it is able to perform a function (don-byed nus-pa). A functional phenomenon able to stand here or able to stand in its own place is one which, in order actually to be taken as a cognitive object, does not require actually being cognitively taken from reliance on another object. Self-sufficiently knowable phenomena can be apprehended in one step.

Self-sufficiently knowable phenomena include:

- forms of physical phenomena,

- ways of being aware of something.

Although forms of physical phenomena, as wholes, are imputable on their physical parts, and ways of being aware of something are imputable on their temporal parts, they are not imputedly knowable. One does not need first to apprehend the parts and then, from reliance on that apprehension, apprehend the wholes. One apprehends the parts and the whole simultaneously.

[See: Self-Sufficiently Knowable and Imputedly Knowable Objects]

Individually Characterized and Generally Characterized Phenomena, and Existence Established as Being Individually Characterized

Individually characterized phenomena (rang-mtshan) are those validly knowable phenomena that have their existence established from the side of their own individual manner of abiding (rang-gi sdod-lugs-kyi ngos-nas grub-pa), without depending on being merely imputed by words or conceptual cognition. In the Sautrantika system, individually characterized phenomena are known as objective entities and include all nonstatic phenomena.

Generally characterized phenomena (spyi-mtshan) have their existence established by their being merely imputed by conceptual cognition (rtog-pas btags-pa-tsam-du grub-pa). In the Sautrantika system, generally characterized phenomena are known as metaphysical entities and include all static phenomena, including the lack of an impossible soul of a person.

In the Chittamatra system, although totally conceptional phenomena are generally characterized phenomena, dependent phenomena and thoroughly established phenomena are individually characterized phenomena. This is because the existence of dependent phenomena and thoroughly established phenomena is not established merely by their being imputed by words and concepts, or merely by their being dependent on words and labels. Both types of phenomena have existence established by individual defining characteristic marks that are findable on their own sides. Thus, the lack of an impossible soul of a person is classified as an individually characterized phenomenon in the Chittamatra system, but as a generally characterized phenomenon in the Sautrantika system.

In the Chittamatra system, then, if something has existence established by individual defining characteristic marks, it is pervasive that it also has existence established as being individually characterized (rang-mtshan-gyis grub-pa). Note that if something has existence not established as being individually characterized, it is not necessarily the case that it is an existent phenomenon. This is because nonexistent totally conceptional phenomena also have existence not established by individual defining characteristic marks. Nonexistent totally conceptional phenomena, after all, are merely imputed by words and concepts.

Substantially Established Existence

Substantially established existence (rdzas-su grub-pa, substantial existence) means existence established by the ability to perform a function. Since all functional phenomena (all nonstatic phenomena) perform a function – they all produce effects – all functional phenomena have substantially established existence.

The sets of substantially established phenomena and self-sufficiently knowable phenomena, then, constitute a trilemma (mu-gsum).

- Things can be substantially established, but not self-sufficiently knowable, such as nonstatic abstractions.

- Things can be both substantially established and self-sufficiently knowable, such as forms of physical phenomena and ways of being aware of something.

- Things can be neither substantially established, nor self-sufficiently knowable, such as thoroughly established phenomena and totally conceptional phenomena.

- There is no fourth possibly. There is nothing that is self-sufficiently knowable, but not substantially established.

Diagram of Types of Phenomena and Ways of Existing