Review of Tibetan Relations with China

Tibet and China had first established diplomatic relations in 608 C.E. when Emperor Songtsen-gampo’s father, Namri-lontsen (gNam-ri slon-mtshan), had sent the first Tibetan mission to the Chinese court at the time of the Sui Dynasty (581 – 618 C.E.). Songtsen-gampo, in turn, had sent a mission to the Tang court in 634 C.E. and had married the Han Chinese princess, Wencheng (Wade-Giles: Wen-ch’eng), in 641 C.E. Four years later, he had commissioned the first Tibetan temple on Wutaishan (Wade-Giles: Wu-t’ai shan, Tib. Ri-bo rtse-lnga), the sacred Chinese Buddhist mountain southwest of Beijing. Since then, Tibet had periodically sent further envoys to the Tang court, despite frequent warfare between the two empires.

Emperor Me-agtsom, a century later, had been particularly interested in Han Chinese Buddhism, undoubtedly due to the influence of his Han Chinese Buddhist wife, Empress Jincheng. Despite the weak state of Buddhism in Tang China after the restrictions imposed upon it by Emperor Xuanzong in 740 C.E., Me-agtsom had sent a mission there in 751 C.E. to learn more about the religion. The interest in Buddhism that his young son, the future Tibetan emperor Tri Songdetsen (Khri Srong-lde-btsan) (742 – 798 C.E.), had shown also purportedly prompted his delegation of the mission. It was led by Ba Sangshi (sBa Sang-shi), the son of a previous Tibetan envoy to Tang China.

In 755 C.E., xenophobic opposition ministers assassinated Emperor Me-agtsom. This was the same faction that sixteen years earlier had expelled the Han Chinese and Khotanese monks from Tibet that the ethnic Han Chinese Empress Jincheng had invited. The assassination occurred in the same year as the An Lushan (Wade-Giles: An Lu-shan) rebellion and, as before, the ministers probably feared that the Emperor’s leanings toward Buddhism and Tang China would bring disaster to Tibet. Perhaps, also, the Abbasid overthrow of the Umayyad Caliphate in 750 C.E. and the An Lushan rebellion encouraged their bold move. Reminiscent of the attack against Han Chinese Buddhism perpetrated by An Lushan, the xenophobic ministers instigated a suppression of Buddhism in Tibet that lasted six years. Its aim, however, was more likely the pro-Tang faction in court.

The Invitation of Shantarakshita to Tibet

The delegation to China, led by Ba Sangshi, returned to Tibet in 756 C.E., bringing with them Buddhist texts. Ba Sangshi temporarily hid the texts, because of the anti-Buddhist atmosphere of the times, but encouraged Tri Songdetsen, still a minor at that time, in the direction of Buddhism.

In 761 C.E., Tri Songdetsen reached adulthood and, upon ascending the throne, officially proclaimed himself a Buddhist. He then sent a delegation to the recently founded Pala Empire (750 - end of the twelfth century) in northern India. He entrusted the mission, headed by Selnang (gSal-snang), to invite the Buddhist master Shantarakshita, the Abbot of Nalanda, to Tibet for the first time.

Shortly after the Indian abbot’s arrival, a smallpox epidemic broke out in Tibet. The xenophobic faction in court blamed the foreign monk for the epidemic and expelled him from Tibet, as they had done to the Han Chinese and Khotanese monks in Tibet when a similar epidemic had erupted in 739 C.E.

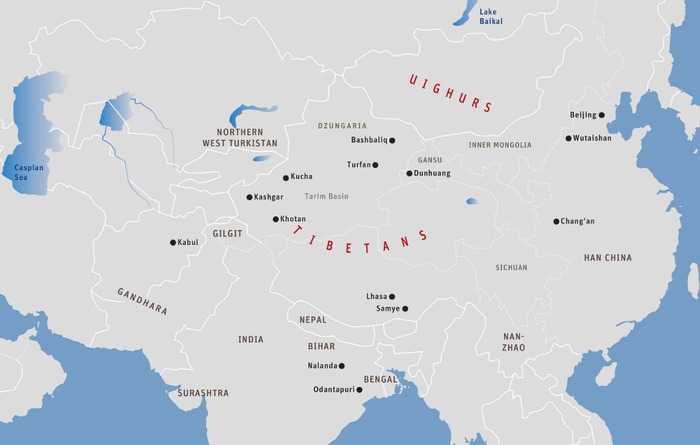

Emperor Tri Songdetsen was not to be thwarted, however, in his intent to strengthen the position of Buddhism in his realm. He was an extremely powerful and ambitious leader. During his reign, Tibet followed an aggressive expansionist policy. Taking advantage of Tang weakness after the An Lushan rebellion, he recaptured large portions of northeastern Tibet that Tang China had previously taken. He even held the Tang capital, Chang’an, briefly in 763 C.E., the year after the conversion to Manichaeism of the Uighur qaghan, Bogu.

Emperor Tri Songdetsen then moved into the Gansu Corridor, blocking Tang China’s direct access to the Silk Route, the main northern branch of which lay between Tang outposts in Turfan and Kucha. This forced Chinese trade to circumvent the Tibetan-held territory by passing to the north through Uighur lands in Inner Mongolia. The Tibetans then entered a protracted three-way war against the Uighurs and Tang China for control of Turfan and Beshbaliq, where the Tang government maintained only nominal charge. Chinese trade, diverted through Inner Mongolia, needed to pass through these two cities to reach the main northern Silk Route.

With his confidence and power bolstered by his military victories, Tri Songdetsen once more dispatched Selnang to India to reinvite Shantarakshita. This time, the Indian abbot brought with him Padmasambhava (Guru Rinpoche), to tame the spiritual forces in Tibet that were inimical to the establishment of Buddhism.

The Building of Samye Monastery

The great Indian Buddhist monastic universities of Bihar, such as Nalanda, the home institution of Shantarakshita, had enjoyed unbroken state support for several centuries, even through changes of political dynasties. Emperor Harsha (606 – 647 C.E.) of the previous Gupta Dynasty had supported a thousand Nalanda monks at his court and had even touched the feet of the Han Chinese monk, Xuanzang (Wade-Giles: Hsüan-tsang), as a sign of respect.

The current Pala Dynasty was patronizing Buddhism to an even greater extent. Its first emperor, Gopala (750 – 770 C.E.), had founded the Buddhist monastic university of Odantapuri, while its second, Dharmapala (770 – 810 C.E.), established Vikramashila and Somapura. Even though Dharmapala had extended his empire to the borders of Gandhara in the west and Bengal in the east, he had never involved the Buddhist monasteries in the political and military vicissitudes of the state. Nor had he tried to regulate them. The monasteries of northern India enjoyed total freedom to pursue religious training.

In 766 C.E., Emperor Tri Songdetsen, inspired by the example of the Indian Emperor Gopala, commissioned Samye Monastery to be built on the model of Odantapuri. It was to be the first Buddhist monastery of the country devoted to use primarily by Tibetans. During the course of its construction, the first seven native Tibetans were ordained as monks and, by the time of its completion in 775 C.E., over three hundred countrymen had joined their ranks. Prior to this, there had only been Buddhist temples in Tibet and a few minor monastic facilities built for foreign monks, such as the Khotanese and Han Chinese refugees of 720 C.E.

Although the Tibetan monks were ordained in the Indian tradition, Emperor Tri Songdetsen pursued a policy of cultural synthesis. Part of his motive for this policy, however, might have been political expediency. He needed to balance demands from three vying factions in his court – native Tibetan, pro-Indian, and pro-Chinese. Thus, he had the main temple at Samye built in three stories, with one story each in the architectural style of Tibetan, northern Indian, and Han Chinese cultures. One is reminded of the founder of his dynasty, Emperor Songtsen-gampo, attempting a similar balance by marrying for political purposes princesses from Zhang-zhung, Nepal, and Tang China.

Cultural Contacts with China

Although Emperor Tri Songdetsen fought against China to gain control of the western end of the Silk Route, he seemed to lack cultural bias against the Han Chinese, particularly regarding Buddhism. His military motives were primarily political and economic.

After the An Lushan rebellion was put down and imperial rule restored, the subsequent Tang emperors not only lifted the restrictions imposed on Buddhism by Emperor Xuanzong, but also patronized the religion. Unlike the case in Pala India, however, the Han Chinese Buddhists, in turn, likewise supported the state. It is unclear whether this came from the Buddhists own initiative or from a state policy to exploit the popularity of Buddhism to bolster support for its rule. The latter seems more likely, given the precedents of the Sui Dynasty founder declaring himself a chakravartin emperor and the Tang Empress Wu declaring herself Maitreya Buddha.

In 766 C.E., the Chinese Emperor Daizong (Wade-Giles: Tai-tsung, r. 763 – 780 C.E.) founded a new monastery on Wutaishan called “The Golden Pavilion Temple that Protects against Demonic Forces and Defends the Nation.” A popular new Han Chinese Buddhist text appeared, The Sutra of the Bodhisattva King Who Defends the Nation. The Tang Emperor reimposed further persecutions against the Manichaeans in 768 and 771 C.E., to defend the “purity” of Buddhism from this religion branded a false imitation.

These developments followed the pattern of northern Chinese Buddhism during the Six Dynasties Period (280 – 589 C.E.). At that time, the non-Han rulers of northern China strictly controlled the Buddhist monasteries and sponsored them to perform rituals for their military success. The monks, in turn, requiring imperial protection to survive the dangerous times, were obliged to acknowledge these rulers as Buddhas, serve their governments, and compromise the purity of the Buddhist teachings so as to sanction even these leaders’ most severe policies.

Emperor Tri Songdetsen was interested to learn more about these recent developments in China, in accord with his policy of pursuing a cultural synthesis of Tibetan, Indian, and Chinese customs. Thus, in the late 760s C.E., he dispatched not only Ba Sangshi, but also Selnang on a second mission to Tang China. On their return, the Emperor built the Nang Lhakang (Nang Lha-khang) Buddhist temple at Dragmar (Brag-dmar). The site was near the imperial court, close to Samye Monastery, which was still under construction. The temple was modeled after the new Golden Pavilion Temple that Protects against Demonic Forces and Defends the Nation. The implication was that Buddhism would take a second place to the state, as in Han China, and be obliged to serve the interests of the ever-growing Tibetan imperial power.

The Completion of Samye Monastery

Samye was completed in 775 C.E. and the Emperor appointed Shantarakshita as its first abbot. Padmasambhava, however, left shortly before its completion. He felt that the Tibetans were not yet ready for the most profound Buddhist teachings, particularly concerning dzogchen (rdzogs-chen, the great completeness). Therefore, he hid texts on the subject in the walls and pillars of the monastery, for later recovery when the times would be riper.

Both northern Indian and Han Chinese teachers were now invited to Samye to help translate and teach Buddhist texts. Originally, however, Samye was not devoted exclusively to Buddhism. Its activities encompassed a larger spectrum of culture. Masters of the indigenous, pan-Tibetan tradition were present as well, to translate materials from the Zhang-zhung language into Tibetan. In this sphere too, Samye reflected the imperial policy of cultural synthesis.

In 779 C.E., the Emperor declared Buddhism the state religion of Tibet. He exempted certain rich families from taxes and assigned them instead the financial support of the fast-growing monastic community. Two hundred families were to provide the resources for the main temple’s offerings in Lhasa, and three families were to donate the provisions for supporting each monk.

Tri Songdetsen was perhaps inspired to take this move by the example of King Shivadeva II (704 – 750 C.E.) of the Nepali Licchavi Dynasty. In 749 C.E., this Nepali king, although not declaring Buddhism the state religion, had assigned an entire village to support his personal monastery, Shivadeva Vihara. Although the Maitraka and Rashtrakuta kings of Saurashtra had a similar policy of support for the monasteries of Valabhi, it is less likely that Tri Songdetsen was aware of this precedent.

Peace with China and Establishment of the Tibetan Religious Council

The Tibetan Emperor, still pursuing a cultural synthesis, requested the new Tang emperor, Dezong (Wade-Giles: Te-tsung, r. 780 – 805 C.E.), in 781 C.E., to send two monks every other year from Han China to Samye to instruct the Tibetans. Two years later, in 783 C.E., Tang China and Tibet, after decades of war over Turfan and Beshbaliq, signed a peace treaty, leaving the Tang forces in control of the two East Turkistani cities.

Shantarakshita, the Indian abbot of Samye, died shortly afterwards, also in 783 C.E. Before passing away, he warned Tri Songdetsen that, in the future, the Buddhist teachings would decline in Tibet because of Han Chinese influence. He advised the Emperor to invite from India his disciple, Kamalashila, to settle the problem at that time.

Tri Songdetsen appointed Selnang to succeed Shantarakshita as the first Tibetan abbot of Samye. In the same year, 783, the Emperor established a Religious Council headed by the Samye Abbot, to decide upon all religious issues. This was the beginning of the Tibetan form of government eventually having both lay and ordained ministers.

Analysis of the Policy of the Tibetan Religious Council

There were three main factions in the Tibetan imperial court at this time – the pro-India, the pro-Tang China, and the xenophobes – each supported by specific clans. Selnang was a member of the clan that led the pro-India faction. Having headed imperial missions to both Pala India and Tang China, he knew how favorably the situation of Buddhism in the former compared with that in latter. In Pala India, the monasteries received state sponsorship and enjoyed total autonomy, without any obligation toward the state. Neither was involved in each other’s affairs. Moreover, since Selnang’s visit, the Pala emperors were sending tribute payments to the Tibetan court, although this description might well have been a euphemism for sending trade delegations. Nevertheless, the hope might have been there that the Pala State would also support Buddhist institutions in Tibet. In Tang China, on the other hand, the Buddhist monasteries received state support only at the price of government control.

Buddhism had frequently been under joint government sponsorship and control in Han China, particularly in the north. However, since the ruling houses were frequently challenged and overthrown, the religion was often on unstable grounds. For example, the Toba Northern Wei Dynasty (386 – 535 C.E.) had a government bureau to administer the Buddhist monasteries in the realm, with a head monk chosen by the emperor. This bureau had the power to expel from the monasteries corrupt monks who flaunted monastic discipline and abused their position. Often the bureau exercised its regulatory functions according to law. However, when the government came under the control of ministers jealous of imperial favor toward Buddhism, the bureau was dissolved and full-scale religious persecutions followed against the Buddhists, for example in 446 C.E.

In establishing a Religious Council, Emperor Tri Songdetsen was perhaps following the Han Chinese model, but he blended certain Indian and Tibetan elements with it. In accord with Indian-Nepali precedents, the state would support the monasteries by exempting certain families from tax and assigning them to provide provisions for the monasteries and monks instead. As in Han China, the monasteries, in turn, would perform rituals for the welfare of the state. This accorded as well with the long-standing Tibetan custom of having priests of Tibet’s native pre-Buddhist tradition serving in the imperial court, performing rituals. As in the Han Chinese model, the bureau would regulate internal Buddhist affairs; but, as in the Indian model, it would enjoy autonomy from government regulation.

Selnang, as a member of the main pro-India clan in the Tibetan court and the first head of the Religious Council, naturally favored closer ties with India and weaker bonds with Tang China. Further, he was especially concerned with avoiding Han Chinese-style government control or persecution of Buddhism. However, Emperor Tri Songdetsen had just bowed to Tang China on the political front. This strengthened the hand of the pro-China faction in the Tibetan court. The situation was ripe for this faction to push the Emperor to implement a Han Chinese-style policy of government control of the monasteries. It was also ripe for the xenophobes at court to react against the strong connection being forged with Tang China and to renew its own purge of foreign influences, including Buddhism.

Selnang and the Religious Council needed to act quickly and decisively. The solution would be to strengthen the Council’s position so that not only would be it autonomous, it would also have a strong influence on the government itself. Thus, Selnang convinced Emperor Tri Songdetsen to allow the members of the Religious Council to attend all ministerial meetings and to have the power to overrule his ministers. Under the Tibetan Abbot’s initial guidance, the Religious Council soon became more powerful than the Emperor’s Council of Ministers itself.

Purge of the Xenophobes

As a first move, in 784 C.E., the Religious Council instituted a purge of the conservative xenophobes, sending its leaders into exile in Gilgit and Nanzhao (Wade-Giles: Nan-chao), present-day northwestern Yunnan Province in the Peoples’ Republic of China. Since this faction had assassinated the Emperor’s father twenty-nine years earlier and had instigated a six-year persecution of Buddhism, they clearly posed the greatest threat.

Twelfth-century C.E. Tibetan Buddhist historical chronicles describe the event as a persecution of the Bon priests who were opposed to Buddhism. Although the later presence of adherents of organized Bon in Gilgit and Nanzhao indicates that many who were sent into exile followed the pre-Buddhist Tibetan tradition, the purge was essentially political in nature. It was not based on religious doctrinal differences. Before the end of the eleventh century C.E., Bon, after all, was not an organized religion and the term bon simply referred to this opposition, xenophobic faction at the imperial court.

Masters of Buddhism and the native Tibetan tradition had worked side by side translating their respective texts at Samye up until then. However, because the political situation was extremely unstable at this point, Drenpa-namka (Dran-pa nam-mkha’), the main spiritual leader of the indigenous system at Samye, hid copies of most of his tradition’s texts for safekeeping in crevices within the monastery walls. Later Tibetan Bon histories, supporting the report of a religious persecution, say that he feigned accepting Buddhism in order to remain at Samye and safeguard these texts. Regardless of his motives, however, it is clear that this native master did stay on at the monastery. After the purge, he taught a hybrid of his tradition and Buddhism to such famous Tibetan masters as the translator Vairochana.

The Tibetan Bon and Buddhist religious histories often depict events in light of their own political agendas. No Tibetan source, however, says that either Drenpa-namka or any of his fellow practitioners of the native tradition were forced to renounce their customs and beliefs and convert to Buddhism. It is much more likely that the Tibetan indigenous tradition and Buddhism had been mixed with each other since at least the time of Emperor Songtsen-gampo. The first Tibetan Emperor had ordered rituals of both traditions to be performed, and Drenpa-namka simply continued and perhaps even furthered this trend. The mutual influence of each religious system on the other would in any case have naturally occurred and grown due to the presence of spiritual masters of both at Samye.

Most, if not all of the xenophobic political faction that had been purged from the imperial court may have followed the Tibetan native tradition. That does not necessarily mean, however, that all practitioners of its rituals or all elements of its system were banished from Tibet, as the religious histories would lead us to believe. In 821 C.E., a second peace treaty with Tang China was concluded with full rituals from the native tradition, including animal sacrifice. The founders of the organized Bon religion and eclectic Bon/Buddhist masters at the beginning of the eleventh century C.E. uncovered the texts hidden by Drenpa-namka. These two facts clearly indicate that the Tibetan Religious Council did not implement a policy of forced conversion to Buddhism. They also indicate that the native faith continued to be tolerated in central Tibet even after the purges of 784 C.E.

Neutralization of the Pro-Tang China Faction

After the purge of 784 C.E., the Tibetan government was left with two opposing factions. Some ministers came from the powerful clan from northeastern Tibet that favored Tang China and from which Empress Dowager Trima Lo had come. The other faction, to which Selnang belonged, came from a rival clan from central Tibet that was distrustful of the Tang court, encouraged continuing wars against it, and sought closer links with Pala India and a strong Religious Council.

In 786 C.E., the three-year peace with Tang China ended. The Uighurs had aided the Jucu (Wade-Giles: Chü-ch’u) rebellion (783 – 784 C.E.) against the Tang ruling house, and the Tibetans had helped the Tang forces defeat them. The Tang court had promised to hand over Turfan and Beshbaliq to the Tibetans as a reward for their help, but when the Tang emperor ignored their agreement, the Tibetans attacked.

Over the next five years, the Tibetans took Dunhuang (Wade-Giles: Tun-huang), from Tang China, eliminated the Tang forces from the competition with the Uighurs for Turfan and Beshbaliq, and reasserted its strong hold over the southern Tarim Basin states, particularly Khotan. The Uighurs took advantage of the situation and, driving their nominal vassals, the Qarluqs, out of Dzungaria and parts of northern West Turkistan, took from Tang China Kucha as well. The Tang forces continued to challenge, however, Tibetan control of the Gansu Corridor.

At this juncture in Sino-Tibetan relations, the Tibetan emperor, Tri Songdetsen, convened the famous debate at Samye (792 -794 C.E.), at which representatives of northern Indian Buddhism defeated the Han Chinese Buddhist monks. This decided once and for all that the main form of Buddhism to be practiced in Tibet would be northern Indian, not Han Chinese. A similar debate and outcome occurred with respect to the medical system to be adopted as well. This development, however, was just as much a triumph of the political view of the anti-Tang China faction as it was of the Indian Buddhist philosophical tenets and practice of medicine. The Religious Council undoubtedly backed the pro-India over the pro-Tang China faction. Furthermore, the fact that Selnang was the interpreter for much of the debate indicates the opportunity he had to influence the outcome.

Summary of Tibetan Policy in Sogdia

Emperor Tri Songdetsen retired in 797 C.E. and died the next year. He was succeeded by his son Muney-tsenpo (Mu-ne btsan-po) (r. 797 – 800). He, in turn, was succeeded by a second son, Tri Desongtsen (Khri lDe-srong-btsan) (r. 800 – 815), also known as Saynaleg (Sad-na-legs). During the latter’s reign, Caliph al-Ma'mun had been fully justified in seeing Tibet as a powerful nation posing a threat, especially when Tibet and its allies were menacing Sogdia and supporting revolt. However, his analysis of Tibet’s motives and his subsequent declaration of the conflict as a holy war were incorrect.

Having reestablished its hold on East Turkistan, Tibet was certainly seeking to extend its territory into West Turkistan and therefore would certainly try to destabilize the rule of its enemies. However, Tibet was not concerned with undermining its enemy’s religion. The Religious Council of monks was obsessed with gaining unopposed internal power within Tibet to ensure the growth of Buddhism in the country. Once it had rid the government of factions that might oppose or try to control it, its main activities were compiling a dictionary for standardizing translations from Sanskrit into Tibetan and regulating which texts to translate so that Buddhism would be best understood and remain pure. It was not concerned with other religions or spreading Buddhism either inside or outside Tibet.

Furthermore, in supporting the Sogdian followers of Musalemiyya Islam and Manichaean Shia in their anti-Abbasid rebellion, Tibet was not at all showing its favor toward their religious sects. Emperor Tri Songdetsen’s edicts concerning the choice of Indian Buddhism as the mainstay for Tibet clearly rejected Manichaeism as well. They repeat the critique of the Tang Chinese Emperor Xuanzong that Manichaeism is a shallow imitation of Buddhism and is based on a lie.

Emperor Tri Ralpachen

One of the main reasons the Abbasids were able to defeat the Tibetan vassal, the Shah of Kabul, in 815 C.E. and make further incursions into Tibetan-held Gilgit in the following years was undoubtedly the death of Tri Desongtsen that year. The new Tibetan emperor, his son Tri Ralpachen (Khri Ral-pa-can, r. 815 – 836 C.E.), ascended the throne as a young child and Tibet did not have strong leadership at the time. Soon afterward, however, as Tri Ralpachen matured, he became extremely powerful and strengthened the position of Buddhism even further.

The Abbasids withdrew from Kabul and Gilgit in 819 C.E., with the founding of the Tahirid state. In 821 C.E., Tibet signed a second peace treaty with Tang China and in the next year reached a similar agreement with the Uighurs. The Tibetans kept the Gansu Corridor and Dunhuang, as well as Turfan and Beshbaliq. The latter two cities had changed hands between the Tibetans and Uighurs several times in the preceding three decades.

Boosted by his victories, Emperor Tri Ralpachen built many new Buddhist temples in celebration of the peace and moved his capital from the Yarlung Valley to Lhasa, the site of the main Buddhist sanctuary in Tibet. According to Tibetan pious histories, Tri Ralpachen also founded a Translation Bureau to compile a Sanskrit-Tibetan dictionary and to standardize the terminology and style of translating Buddhist texts. Actually, these projects began under his father, Emperor Tri Desongtsen. The pious histories ascribed them to him, however, to support their identification of Songtsen-gampo, Tri Songdetsen, and Tri Ralpachen as the three main imperial patrons of Buddhism at the time and thus incarnations of the Buddha-figures Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, and Vajrapani. This echoes these histories ascribing the three Buddha-figures as the patron Buddhas of Tibet, China and the Manchus, and Mongolia, respectively, and the Gelug founder, Tsongkhapa (Tsong-kha-pa Blo-bzang grags-pa, 1357 – 1419 C.E.), as the embodiment of all three.

Like the fierce figure Vajrapani, however, Emperor Tri Ralpachen became slightly fanatic in his religious fervor. He not only increased the number of families assigned to support each monk from three to seven, putting a serious strain on the state economy, but decreed that anyone pointing a derisive finger at a monk would have it cut off. With Buddhism in such a strong position and the Abbasids’ attention diverted elsewhere, the conversion to Islam of the Shah of Kabul had little lasting impact on the spread of Islam to Tibet or its vassal states in Kabul or Gilgit.

The Breakup of the Tibetan Empire

In 836 C.E., Emperor Ralpachen of Tibet was assassinated by his brother, Langdarma (gLang-dar-ma, r. 836 – 842). Assuming the throne, the new emperor instituted a severe repression of Buddhism throughout Tibet. It was aimed at ending the Religious Council’s interference in politics and the drain on the economy made by Tri Ralpachen’s policy of legislating ever more grandiose public support of the monasteries. Emperor Langdarma closed all the monasteries and forced the monks to disrobe. He did not physically destroy these complexes, however, or their libraries. Even without access to the scriptural literature, Buddhism continued among many Tibetan lay practitioners.

In 842 C.E., Langdarma was assassinated by a monk who, according to one scholar, was the deposed head of the Religious Council and former abbot of Samye. Civil war ensued over succession to the throne, resulting in the breakup of the Tibetan Empire. Over the next two decades, Tibet gradually withdrew from its holdings in Gansu and East Turkistan. Some became independent political entities - first Dunhuang, which became known as the state of Guiyijun (Wade-Giles: Kuei i-chün, 848 – 890s C.E.) governed by a local Han Chinese clan, and then Khotan (851 – 1006 C.E.) ruled by its own, unbroken royal line. In others, local Han Chinese took initial control but did not establish a strong rule, for instance Turfan, starting in 851 C.E. By 866 C.E., however, the Uighur immigrant communities in these former Tibetan holdings had become strong enough to establish their own rule.

The Situation in the Tibetan Regions

Meanwhile, central Tibet was slowly recovering from the civil strife that had followed the assassination of Langdarma in 842. After several weak reigns of the last emperor’s adopted son and his successors, Tibet divided in 929 C.E. into two kingdoms. One continued on a weak political level in central Tibet and the other, the Ngari (mNga’-ris) Dynasty, established itself in the old Zhang-zhung homeland in the west. Eventually, both became interested in reviving the Buddhist monastic tradition from the monks in Tsongka (Tsong-kha), northeastern Tibet.

Buddhism in Tsongka had continued to thrive, unaffected by Langdarma’s persecution. In 930 C.E., Tibetans from this area began to help translate Buddhist texts from their language into Uighur. This was five years after the Khitans had adopted the Uighur script as their second writing system and, thus, was the period when Uighur cultural influence on the Khitans was reaching its height. It is unclear if the religious cooperation of the Tsongka Tibetans with the Uighurs was exclusively with their immediate neighbors to the north, the Yellow Yugurs, or also with the Qocho Uighurs further to the west. The two Turkic groups shared the same language and culture.

Tibeto-Uighur religious contact and translation work increased during the second half of the tenth century C.E., especially during the time when the Tibetans and Yellow Yugurs were allied in war against the Tanguts. The Han Chinese pilgrim, Wang Yande (Wade-Giles: Wang Yen-te), visited the Yellow Yugur capital in 982 C.E., the year the Tangut Empire was founded, and reported more than fifty monasteries.

King Yeshe Ö’s Efforts to Revitalize Buddhism in Western Tibet

The Buddhist monastic lineage of ordination was revived in central Tibet in the mid-tenth century C.E. from the central Tibetan monks who had fled to Tsongka and then moved on to Kham.

[See: The Origin of the Yellow Hat]

Subsequently, the Ngari kings of western Tibet made great efforts to restore Buddhism even further to its previous level. In 971 C.E., King Yeshe Ö (Ye-shes 'od) sent Rinchen Zangpo (Rin-chen bzang-po, 958 – 1055 C.E.) and twenty-one youths to Kashmir for religious and language instruction. They also visited Vikramashila Monastic University in the central part of northern India.

Kashmir, at this time, was in the final phases of the Utpala Dynasty (856 – 1003 C.E.) that had followed Karkota rule. The Utpala period had witnessed much civil war and violence in Kashmir. Certain aspects of Buddhism had become mixed with the Shaivite form of Hinduism. However, by the beginning of the tenth century C.E., Kashmiri Buddhism had received new impetus with the revival of Buddhist logic from the northern Indian monastic universities. A brief setback had occurred during the rule of King Kshemagupta (r. 950 – 958 C.E.), when this zealous Hindu ruler had destroyed many monasteries. However, by the time of Rinchen Zangpo’s visit, Buddhism was slowly being reestablished.

Although Buddhism had recently reached its high point in Khotan, which had for centuries been closely connected with western Tibet, the armed struggle between Khotan and the Qarakhanids had begun in Kashgar in the year of Rinchen Zangpo’s departure. Khotan was no longer a safe place for Buddhist study. Furthermore, the Tibetans wished to learn Sanskrit from its source in the Indian subcontinent and translate themselves from the original tongue. Khotanese renditions of Sanskrit Buddhist texts were often paraphrases, whereas the Tibetans, plagued by confusion about Buddhist doctrine, wished for more accuracy. Thus, despite Buddhism also being in a precarious position in Kashmir, it was the only relatively safe, nearby place where the Tibetans could receive reliable instruction.

Only Rinchen Zangpo and Legpay-sherab (Legs-pa'i shes-rab)survived the journey and training in Kashmir and the northern Indian Gangetic Plains. Upon his return to western Tibet in 988 C.E., Yeshe Ö had already established several Buddhist translation centers with the Kashmiri and Indian monk scholars that Rinchen Zangpo had sent back to Tibet with numerous texts. Monks invited from Vikramashila started a second line of monastic ordination.

In the last years of the tenth century C.E., Rinchen Zangpo built several monasteries in western Tibet, which at that time included portions of Ladakh and Spiti in present-day trans-Himalayan India. He also visited Kashmir twice more to invite artists to decorate these monasteries so as to attract the devotion of the common Tibetan. This was despite a change of dynasty in Kashmir, with the founding of the First Lohara line (1003 – 1101 C.E.). The dynastic transition was peaceful and did not disturb the situation of Kashmiri Buddhism.

The Qarakhanid siege of Khotan had begun in 982 C.E., six years before Rinchen Zangpo’s return. On his arrival, many Buddhists were already flocking to western Tibet as refugees, which undoubtedly also helped with the revival of Buddhism there. They were probably from Kashgar and the areas between there and Khotan that lay along the Qarakhanids’ line of supply. Although most who fled would have passed through Ladakh on their way to Tibet, they did not turn to the west and settle in nearby Kashmir, a much less difficult and shorter journey. This was perhaps due to the Ngari Kingdom appearing to be more politically and religiously stable in face of Yeshe Ö’s strong rule and patronage. Another factor may have been the long cultural ties between the region and Tibet. In 821 C.E., Khotanese monks had also fled to western Tibet seeking refuge from persecution.

Tibetan Military Aid to Khotan

The western Tibetan Ngari Kingdom was just a few years old when the Qarakhanids of Kashgar converted from Buddhism to Islam in the 930s C.E. Having arisen as a political entity from a split with central Tibet over a succession issue in 929 C.E., Ngari was at first militarily weak. It could hardly risk enmity with the Qarakhanids because of religious differences. In order to survive, it would have had to maintain friendly relations with its neighbors.

According to later Tibetan Buddhist histories, however, King Yeshe Ö of Ngari went to the aid of besieged Khotan around the turn of the eleventh century C.E. This was undoubtedly due as much to fear of further Qarakhanid political expansion as it was to concern for the defense of Buddhism. Although the Tibetans and Qarluq/Qarakhanids had been allies for centuries, they had never threatened each others’ territories. Furthermore, Tibet had always considered Khotan within its legitimate sphere of influence. Therefore, once the Qarakhanids overstepped the boundary of this sphere, relations between the two nations changed.

According to traditional Buddhist histories, King Yeshe Ö was taken hostage by the Qarakhanids (Tib. Gar-log, Turk. Qarluq), but did not allow his subjects to pay the ransom. He advised them to let him die in prison instead and use the funds to invite more Buddhist teachers from northern India, specifically Atisha from Vikramashila. Many Kashmiri masters were visiting western Tibet at the beginning of the eleventh century C.E. and several were spreading corruptions of Buddhist practice there. As this was compounding the already poor level of understanding of Buddhism in Tibet due to the destruction of the monastic centers of study at the time of Langdarma, Yeshe Ö wished to clear this confusion.

There are many historical inconsistencies in this pious account of Yeshe Ö’s sacrifice. The siege of Khotan ended in 1006 C.E., while Yeshe Ö issued a final edict from his court in 1027 C.E. to regulate the translation of Buddhist texts. Thus, he did not die in prison during the war. According to Rinchen Zangpo’s biography, the king died of sickness in his own capital.

Nevertheless, this apocryphal account indirectly indicates that the western Tibetans were not a strong military power at the time. They were not effective in lifting the siege of Khotan and did not pose a serious threat to any future Qarakhanid expansion along the southern Tarim branch of the Silk Route. They would not be able to defend the Tibetan nomads living there.

[See: The Life of Atisha]

The Disappearance of Buddhism in Khotan

Accounts of the Qarakhanid occupation of Khotan, following the siege and subsequent uprising, are marked by a silence concerning the native population. One year after the insurrection was crushed, the Khotanese trade and tribute mission sent to Han China contained only Turkic Muslims. The Turkic language of the Qarakhanids totally replaced Khotanese and the entire state became Islamic. Buddhism completely disappeared.

The Tibetans lost contact with their former possession to such an extent that the Tibetan name for Khotan, Li, lost its original meaning and came to refer to the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal as an acronym for its former ruling dynasty, the Licchavi (386 – 750 C.E.). All the Buddhist myths concerning Khotan were transferred to Kathmandu as well, such as its founding by Manjushri draining a lake by cleaving a mountain with his sword. By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries C.E., the Tibetans lost sight that these myths had ever been associated with Khotan. Thus, the Tibetan Buddhist accounts of the sacrifice of King Yeshe Ö have his imprisonment by the “Garlog,” i.e. the Qarakhanid Qarluqs, anomalously occurring in Nepal. Although there was a civil war in Nepal between 1039 and 1045 C.E., there were hardly any Turkic tribes there, yet alone Qarluqs at the time.

The Revival of Buddhism in Central Tibet

Throughout the eleventh century C.E., a steady stream of Tibetans went to Kashmir and northern India to study Buddhism. Many brought back with them masters from these regions to help revive Buddhism in newly constructed monasteries in their land. Although the initial activity in this direction came from the Ngari Kingdom of western Tibet, it soon spread to the central part of the country as well, starting with the founding of Zhalu (Zha-lu) Monastery in 1040 C.E.

Each Indian master or returning Tibetan student who arrived in Tibet brought with him or her lineage of a particular style of Buddhist practice. Many of them built monasteries around which crystallized not only religious, but also secular communities. It was not until the thirteenth century C.E. that clusters of these transmission lineages consolidated to form the various sects of the so-called “New Period” schools of Tibetan Buddhism – Kadam (bKa’- gdams), Sakya (Sa-skya) and a number of different lines of Kagyu (bKa’- brgyud).

Other eleventh century C.E. Tibetan masters began to discover the texts that had been hidden for safekeeping in central Tibet and Bhutan during the turbulent years of the late eighth and early ninth centuries C.E. The Buddhist ones found became the scriptural basis for the “Old Period” or Nyingma (rNying-ma) school, while those from the indigenous Tibetan tradition, recovered slightly earlier, formed the foundation for establishing the organized Bon religion. Several masters discovered both types of text, which were often very similar to each other. Organized Bon, in fact, shared so many features in common with both the New and Old Translation Buddhist schools that subsequent masters from each of the religions claimed that the other had plagiarized from them.

The Ngari royal family continued to play an important role in sponsoring not only the translation of Buddhist texts freshly brought from Kashmir and northern India, but also the revision of previous translations and the clarification of misunderstandings about certain delicate points of the religion. The Council of Toling (Tho-ling), convened by King Tsedey (rTse-lde) at Toling Monastery of Ngari in 1076 C.E., gathered together translators from the western, central and eastern regions of Tibet, as well as several Kashmiri and northern Indian masters, and was instrumental in coordinating the work. The 1092 C.E. edict of Prince Zhiwa Ö (Zhi-ba ‘od) set the standards for determining which texts were reliable.