Review of Mental Urges in Karmic Actions of the Mind

In the previous part of this series, we modified Vasubandhu’s Sautrantika presentation of the division between performer impulses (byed-pa’i las, Skt. kāritrakarma) and exertional impulses (rtsol-ba-can-gyi las, Skt. vyavasāyakarma) and applied the terms to his Vaibhashika presentation of mental urges as impulses of the mind.

- A “performer non-karmic impulse” is the mental factor of an urge (sems-pa, Skt. cetanā) that affects and drives a mental consciousness in a non-conceptual or conceptual cognition or one of the five types of sensory consciousness (which occur only in non-conceptual cognition), together with its other accompanying mental factors, to move toward a cognitive object and to cognize it.

- A “karmic exertional impulse” is the mental factor of an urge that affects and drives a mental consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors in a conceptual cognition during the course of a karmic action of the mind that engages the body or speech by thinking about and deciding to commit a specific karmic action with one of the two.

- A “non-karmic exertional impulse” is the mental factor of an urge that affects and drives a sensory consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors in a non-conceptual cognition during the course of a karmic action of the body or speech that engages the body or speech in committing the karmic action.

The mental factor of an urge is able to perform either of these two functions – the non-karmic one of a performer impulse and the karmic or non-karmic one of an exertional impulse – by sharing five congruent features in common (foundation, focal object, aspect, time, and substantial entity) with the consciousness involved and its other accompanying mental factors.

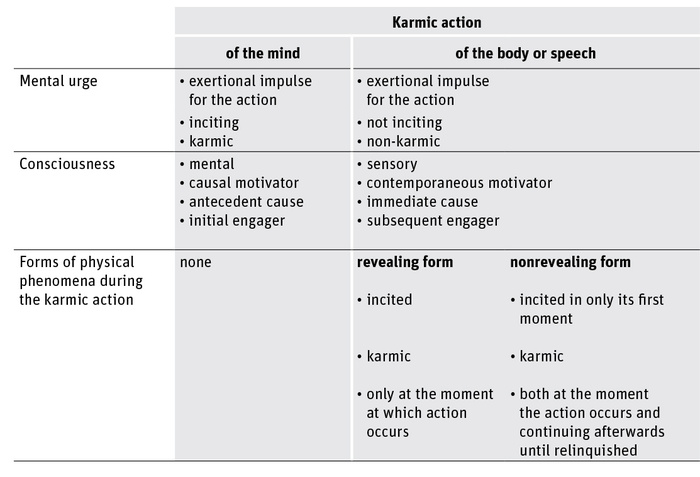

In the presentation of the ten destructive and ten constructive actions of body, speech and mind, the consciousness in one of the three destructive or three constructive actions of the mind is:

- A mental consciousness

- The causal motivator (rgyu’i kun-slong, Skt. hetūttāna) and antecedent cause (brgyud-rgyu) for the arising of a subsequent destructive or constructive revealing form (rnam-par rig-byed-kyi gzugs, Skt. vijñaptirūpa) of the body or speech.

- The initial engager (rab-tu ’jug-byed-pa, Skt. pravartika) of the body or speech.

- The mental urge that drives this mental consciousness is a karmic exertional impulse.

The consciousness in one of the three destructive or three constructive actions of the body or speech is:

- One the five types of sensory consciousness

- The contemporaneous motivator (dus-kyi kun-slong, Skt. tatkṣaṇotthāna) and immediate cause (dngos-kyi-rgyu, Skt. sakṣātkāraṇa) for the arising of the destructive or constructive revealing form in the action.

- The subsequent engager (rjes-su ’jug-byed, Skt. anuvartika) of the body or speech.

- The mental urge that drives this sensory consciousness is a non-karmic exertional impulse.

What is the relation between a performer urge and an exertional urge? Let us first analyze when the exertional urge is a karmic one.

Analysis of the Relation between a Performer Non-Karmic Impulse and a Karmic Exertional Impulse in a Karmic Action of the Mind

Consider the case, for instance, of thinking covetously about stealing a specific watch. The mental urge in this karmic action of the mind operates as a performer non-karmic impulse since, in thinking over and deciding to steal this watch, it causes the mental consciousness and its accompanying other mental factors to move in a conceptual cognition toward the specific watch one thinks to steal and the shape of the hand snatching it. Again, this conceptual cognition must be understood as occurring with that watch and that shape of the hand arising simultaneously with the mental urge, the mental consciousness and the other accompanying mental factors that cognize them.

While moving the mental consciousness in this conceptual cognition of covetous thinking such that the consciousness cognizes the watch one thinks to steal and the shape of the hand snatching it, the mental urge is simultaneously driving the mental consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors during the course of thinking over and deciding to steal the watch. In doing so, it engages the body in the sense that it considers stealing the watch by means of a certain shape of the body – this shape of the body snatching the watch. In this way, the mental urge operates as both a performer non-karmic impulse and a karmic exertional impulse.

Conceptual Cognition According to Vaibhashika

How does Vaibhashika explain the watch or the shape of the hand snatching it that are focusing upon by a conceptual mental consciousness and its accompanying mental factors during the destructive karmic action of the mind of covetously thinking about and deciding to steal this watch? Further, how do such objects cognized by a conceptual mental consciousness when thinking about stealing the watch compare with the objects cognized by a non-conceptual eye consciousness when actually stealing it? To understand this, we need to look at another Vaibhashika assertion. To simplify the discussion, let us restrict our consideration to just the watch as the object of focus.

Among the Buddhist tenet systems, Vaibhashika uniquely asserts that all validly knowable phenomena, including material objects such as a watch, exist as substantial entities in all three times and, as such, function in all three times (at least minimally as the source of a cognition of it). Thus, all validly knowable phenomena exist, literally, first as not yet come about (ma-’ong-pa, Skt. anāgata), then as presently occurring (da-lta-ba, Skt. vartamāna) and, after that, as already passed (’das-pa, Skt. atīta).

In the case of material objects such as a watch, those that have not yet come about or that have already passed are not located anywhere, whereas material objects that are presently occurring performing functions such as indicating the time and ticking are located somewhere.

In the context of the Prasangika tenet system, which refutes substantially established entities, I have consistently translated these terms for the three times as “not yet happening,” “presently happening” and “no longer happening.” For the sake of consistency, I shall also use these translation terms here in the context of Vaibhashika, but as having the connotations just explained.

In the case of the watch that one intends to steal, then, there exist as cognizable substantial entities the not-yet-happening watch, the presently-happening watch and the no-longer-happening watch. They are externally existent, nonstatic, performer phenomena that are each comprised of the four great elements (earth, water, fire and wind) and that can each perform the function of serving as objects of cognition.

Only the sight of the presently-happening watch, however, can be detected and “seen” by the eye-sensors (the photosensitive cells of the eyes) and cognized by eye consciousness. The sights of the not-yet-happening watch and of the no-longer-happening watch are not visible to the eye-sensors. They can be cognized and thought about, however, by mental consciousness in a conceptual cognition. However, just as eye consciousness, being nonmaterial, cognizes the sight of the presently-happening watch when stealing it without representing that sight with a mental aspect resembling a mental hologram of a watch, likewise conceptual mental consciousness cognizes the sight of the not-yet-happening watch when thinking about and deciding to steal it, also without representing that sight with a mental aspect resembling a mental hologram of a watch. In both cases, the consciousness cognizes its object directly without taking on an aspect of that object.

Analysis of the Relation between a Performer Non-Karmic Impulse and a Non-Karmic Exertional Impulse in a Karmic Action of the Body or Speech

In the case a karmic action of the mind, such as when covetously thinking about and deciding to steal a watch, the mental urge that drives the conceptual consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors during the course of the action operates as both:

- A performer non-karmic impulse cognizing the not-yet-happening watch and the not-yet-happening shape of the hand snatching it

- A karmic exertional impulse driving the mind to think about and decide to steal it.

Thus, there is only one mental urge involved in the covetous thinking. Although there can be performer non-karmic impulses that are not also exertional ones – for instance, when simply looking at your watch to know the time – it is unclear in the texts whether the non-karmic exertional urges for karmic actions of the body and speech are also performer ones. Let us analyze the karmic action of the body stealing a watch, for example, and explore whether there is only one mental urge involved or there are two.

The Case of There Being Two Mental Urges

Consider first the case of there being two mental urges involved in the karmic action of the body in stealing the watch:

- A performer non-karmic urge – a mental urge that moves the eye consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors to cognize the sight of the shape of the hand snatching the watch and the watch in the hand snatching it, as detected and “seen” by the photosensitive cells of the eyes.

- A non-karmic exertional urge – a mental urge that moves another sensory consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors to cause the karmic action of the stealing to occur by causing the arising of the revealing form of the shape of the hand snatching the watch.

If that were the case, which of the five types of sensory consciousness would the consciousness be that the non-karmic exertional urge moves to cause the stealing to occur and what is the object that it cognizes?

Whether snatching someone else’s watch when stealing it or picking up your own watch when putting it on your wrist, body consciousness cognizes the physical sensation of the hand contacting the watch when the physical sensation-sensitive cells of the hand detect and “feel” that physical sensation. That physical sensation is a physical sensation of the ripened body, not the physical sensation of the revealing form of the shape of the hand. The revealing form of the shape of the hand – whether the destructive one when stealing the watch or the unspecified one when merely picking up your own watch – is a visible sight, not a physical sensation.

Vasubandhu, however, in his Autocommentary to “A Treasure House of Special Topics of Knowledge” (Chos mngon-pa’i mdzod-kyi bshad-pa, Skt. Abhidharmakośa-bhāṣyā) (Gretil 194.22–23, Derge Tengyur vol. 140, 167B–168A), makes it clear that a revealing form of the body (the shape of the body as a method implemented for causing the action of the body to take place) cannot be cognized by both an eye consciousness and a body consciousness. It can only be cognized by an eye consciousness:

If, when something visual has been seen and makes itself understood as being “long,” it also has been physically sensed (as being long) by a body sensor, then it would lead to its being cognitively taken (as a cognitive object) by two (types of consciousness). But there is no (such thing as the) cognitive taking of a cognitive stimulator that is a sight (as a cognitive object) by two (types of consciousness).

(Skt.) cakṣuṣā hi dṛṣṭvā dīrghamityavasīyate kāyendriyeṇāpi spṛṣṭveti dvābhyāmasya grahaṇaṃ prāpnuyāt / na ca rūpāyatanasya dvābhyāṃ grahaṇamasti

(Tib.) mig gis mthong na yang ring po’o snyam du shes par ’gyur la/ lus kyi dbang po reg na yang shes par ’gyur bas ’di dbang po gnyis kyi gzung bar ’gyur ba zhig na/ gzugs kyi skye mched la ni gnyis kyis ’dzin pa med do//

A cognitive stimulator that is a sight (gzugs-kyi skye-mched, Skt. kāyendriya) includes:

- The sights of presently-happening material objects, which are visible and can be detected and “seen” by the eye-sensors and cognized non-conceptually by eye consciousness, but not by any other type of sensory consciousness

- The sights of both not-yet-happening and no-longer-happening material objects, which are invisible to eye consciousness, but which can be cognized by mental consciousness in a conceptual cognition by means of an aspect representing them.

Furthermore, the consciousness that causes a revealing form of the body or speech to arise in a karmic action of the body or speech can be any of the five types of sensory consciousness, including eye consciousness, and not just body consciousness. So, we can rule out there being two mental urges involved in the karmic action of the body in stealing the watch – one a performer non-karmic urge driving an eye consciousness and its accompanying mental factors and one a non-karmic exertional urge driving a body consciousness and its accompanying mental factors. This is because the revealing form of the shape of the hand stealing the watch, as a visible sight, can only be cognized by an eye consciousness and not by a body consciousness. The body consciousness cognizing the physical sensation of the hand contacting the watch, then, cannot be the consciousness causing (motivating) the revealing form to arise.

This is quite different from cognizing with eye consciousness the sight of the watch while snatching it and simultaneously cognizing with body consciousness the physical sensation of the watch in one’s hand while snatching it. In that case, there are two simultaneously occurring cognitions by two different types of sensory consciousness of two different types of objects, and thus two different non-karmic exertional urges affecting the cognitions.

The Case of There Being Only One Mental Urge

Consider the case of there being only one mental urge. In such a case, the mental factor of an urge operates both as a performer non-karmic impulse and as a non-karmic exertional impulse.

Operating as a performer non-karmic impulse, the mental urge moves the eye consciousness and its accompanying mental factors to cognize the presently-happening sight of the watch one intends to steal. It does this by sharing five congruent features in common with the eye consciousness and the other accompanying mental factors.

Operating also as the non-karmic exertional impulse for this karmic action of the body, the mental urge cannot share five congruent features in common with another consciousness – for instance, a body consciousness – and its set of other accompanying mental factors while also sharing five congruent features with the eye consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors in cognizing the watch. A mental urge cannot simultaneously be congruent with two different types of consciousness and two different sets of other mental factors. Thus, the performer non-karmic mental urge, operating in its capacity as a non-karmic exertional urge, also moves the eye consciousness to engage the body such that it causes the arising of the revealing form of the karmic action (the shape of the hand snatching the watch) while cognizing the watch.

The eye consciousness, accompanied by the mental factor of attention (yid-la byed-pa, Skt. manasikāra), is focused on the sight of the watch and not on how to hold the hand in a position with such a shape that it can snatch the watch. Knowing how to hold the hand in such a position with such a shape as to be able to pick up something comes from familiarity with that position of the fingers gained from infancy and what, in the West, might be called “muscle memory.”

This conclusion that a mental urge moves eye consciousness, for example, to simultaneously cognize an object – referred to as “the basis for a karmic action,” such as the watch in our example – and engage the body in committing a karmic action of the body (stealing the watch) explains how eye-hand coordination works. The explanation holds true not only for the seven destructive and seven constructive karmic actions of the body and speech, but also for all actions of body and speech requiring eye-hand coordination or coordination between any cognitive sense and any part of the body.

For example, when playing the piano while looking at a sheet of music, one does not focus one’s attention on body consciousness moving the fingers; one just focuses one’s attention in each moment on eye consciousness reading the notes on the sheet music. Of course, to be able to do this, one needs to have trained the hands to play the notes that correctly correspond to the sheet music, but then “muscle memory” takes over.

The same mechanism occurs with looking at the road while one’s hand moves the steering wheel, looking at the digital display while playing a video game, listening to a song and singing along with it, and physically sensing a partner’s movement when ballroom dancing and following their steps.

In short, whether it is a karmic action of the mind, body or speech, there is only mental urge that is driving one type of consciousness and one set of other accompanying mental factors in committing the action:

- In a karmic action of the mind, the mental urge drives a mental consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors and functions as both a performer non-karmic impulse and a karmic exertional impulse.

- In a karmic action of the body or speech, the mental urge drives a sensory consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors and functions as both a performer non-karmic impulse and a non-karmic exertional impulse.

Analysis of Types of Impulses According to Sanskrit Grammar

Sanskrit, the original written language of the material we are examining regarding karma, like many other languages, uses many terms and phrases that have several meanings. Confusion often arises from not applying the intended meaning in a specific passage. Let us try to untangle some of the possible confusion that may arise.

The Term “Karma”

For example, we have seen that the Sanskrit term karma means an impulse. An impulse can be:

- An impulse of the mind, in which case “karma” refers to the mental factor of an urge, or

- An impulse of the body or speech, in which case “karma” refers to a revealing form (rnam-par rig-byed-kyi gzugs, Skt. vijñaptirūpa) or a nonrevealing form (rnam-par rig-byed ma-yin-pa’i gzugs, Skt. avijñaptirūpa).

Further, an impulse of the mind (the mental factor of an urge) may be:

- A performer non-karmic urge in the context of the mental or sensory cognition of a cognitive object

- A karmic exertional urge that drives a mental consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors during a karmic action of the mind that thinks over and decides whether to commit a karmic action of the body or speech by means of engaging the body or speech

- A non-karmic exertional urge that drives a sensory consciousness during a karmic action of the body or speech and engages the body or speech to commit the karmic action.

Only exertional impulses (mental urges) in a karmic action of the mind and impulses of the body or speech (revealing and nonrevealing forms) in karmic actions of the body or speech are examples of the second noble truth, true origins of suffering. We shall therefore restrict the term “karmic impulse” to refer only to an exertional impulse of the mind and to a revealing or nonrevealing form.

The Term “Manas”

We have also seen that the Sanskrit term manas, mind, has both:

- A general meaning as mental and sensory consciousness, and

- A specific meaning as only mental consciousness.

Further, manas in either its general or specific meaning in the term manaskarma, impulse of the mind, has both:

- A general usage to refer to both performer and exertional impulses, and

- A specific usage to refer to only exertional impulses.

In the following discussion, let us restrict the meaning of manaskarma to just its specific usage to refer to only exertional impulses.

The Terms “Kāyakarma,” “Vākkarma” and “Manaskarma”

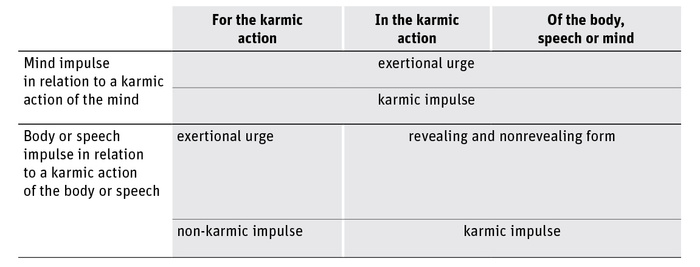

The terms kāyakarma, vākkarma and manaskarma translate literally as “body impulse,” “speech impulse” and “mind impulse.” Each of these three terms is a Sanskrit compound made of two words that may be connected in several ways. These impulses may be presented as impulses:

- For the body, speech or mind – meaning for (actions of) the body, speech or mind

- In the body, speech or mind – meaning in (actions of) the body, speech or mind, or

- Of the body, speech or mind – meaning in the nature of the body, speech or mind.

This variety of meanings arises because, according to Sanskrit grammar, these three compound nouns are so-called tatpuruṣa compounds. The two words in such compounds may be connected in a variety of grammatical ways. In this case, the two words comprising the compounds – (1) kāya, vāk or manas (referring either to body, speech or mind or to actions of the body, speech or mind) and (2) karma (impulses) – may be connected in either a dative, locative or genitive sense.

- In the dative sense, the impulses are “for the sake of” or, more simply, “for” karmic actions of the body, speech or mind. They are the exertional impulses that arise for the sake of driving karmic actions of the body, speech or mind and thus are all the mental factor of an urge. In the Vaibhashika system, only the exertional impulses (the mental urges) that are for driving karmic actions of the mind are karmic. The exertional impulses (the mental urges) that are for driving karmic actions of the body or speech are non-karmic.

- In the locative sense, the impulses are “in the location of,” “in the context of” or, more simply, “in” karmic actions of body, speech or mind. The impulses in karmic actions of the mind are exertional impulses (mental urges), while the impulses in karmic actions of the body or speech are revealing and nonrevealing forms. With this usage of the terms, the impulses in karmic actions of the body, speech and mind are all karmic impulses.

- In the genitive sense, the impulses are aspects “of” the body, speech or mind, in the sense of being in the nature of the body, speech or mind. Impulses of the mind include both performer and exertional urges, while impulses of the body or speech are revealing and nonrevealing forms. In this sense, as well, only exertional impulses of the mind and impulses of the body and speech are karmic impulses.

Inciting and Incited Karmic Impulses

Let us examine more deeply the karmic impulses “in” karmic actions of body, speech and mind. In this context, the karmic impulses in karmic actions of the mind are the mental factor of an urge. The karmic impulses in karmic actions of the body and speech are forms of physical phenomena – namely, revealing forms and nonrevealing forms.

The karmic impulses (urges) in actions of mind are of two types:

- In the context of the presentation of the ten destructive and ten constructive actions, the karmic impulses in the three destructive and three constructive actions of the mind are the exertional urges that engage conceptual mental consciousness in thinking over and deciding to enact or to refrain from enacting one of the seven destructive or seven constructive actions of body and speech. The mental consciousness in this karmic action of the mind is the causal motivator and antecedent cause for the arising of a revealing form of the body or speech in a subsequent karmic action of the body or speech and is also the initial engager of the body or speech. The karmic action of the body or speech, however, may or may not be subsequently enacted. In either case, the exertional urges that are these karmic impulses are called in Sanskrit cetanākarma (Tib. sems-pa’i las), which literally translates as an “urging karmic impulse.” For the sake of clarity, let’s call them “inciting karmic impulses.”

- The karmic impulses in actions of the mind may also not be inciting karmic impulses, as in the case of the mental factor of an urge that is a throwing karmic impulse (’phen-byed-kyi las) at the end of a lifetime, which propels the mental consciousness to a next rebirth. Such a karmic impulse of the mind falls outside the scope of the karmic impulses of the mind in one of the three destructive or three constructive actions of the mind; it does not drive a mental consciousness and its other accompanying mental factors to think over and decide to commit a karmic action of the body or speech. Although a throwing karmic impulse is a true origin of suffering, it also falls outside the scope of exertional urges since it does not drive a consciousness in committing a karmic action.

Out of the revealing and nonrevealing forms that are the karmic impulses in actions of the body and speech, the revealing forms are also of two types:

- The first phase of a revealing form in a karmic action of the body or speech subsequent to a karmic action of mind in which the karmic impulse (the karmic exertional urge) was an inciting one is called in Sanskrit cetayitvākarma (Tib. bsams-pa’i las) – literally, a “karmic impulse being caused by an urging.” The “urging” here is by means of an inciting karmic impulse. Let’s call this first phase of a revealing form an “incited karmic impulse.”

- The karmic impulse in a karmic action of the body or speech may also not be an incited one, as in the case of the revealing form of the body or speech in (1) an unplanned, spontaneous karmic action of the body or speech or in (2) a karmic action of the body or speech arising in accord with subsequently keeping monastic vows after having requested and taken them on.

- The sensory consciousness that the non-karmic exertional impulse (a mental urge) drives to engage the incited revealing form of the body or speech is the contemporaneous motivator and immediate cause for the arising of the revealing form in the karmic action and the subsequent engager of the body or speech.

A nonrevealing form arises only with an incited revealing form, in which case the first moment of the nonrevealing form is also an incited karmic impulse. Subsequent moments in the continuum of the nonrevealing form, however, are not considered incited karmic impulses. This will be explained in a later part of this series.

Vasubandhu introduces inciting and incited karmic impulses in A Treasure House of Special Topics of Knowledge, Put in Verses (Chos mngon-pa’i mdzod-kyi tshig-le’ur byas-pa, Skt. Abhidharmakośa-kārikā) (IV.1) (Gretil ed., Derge vol. 140, 10B):

The diversity of (external and internal) mundane (phenomena) is generated from karmic impulses: an urge and that which is made (to arise) by it. An urge is a mental karmic impulse. Those generated by it are karmic impulses of the body and speech.

(Skt.) karmajaṃ lokavaicitryaṃ cetanā tatkṛtaṃ ca tat, cetanā mānasaṃ karma tajjaṃ vākkāyakarmaṇī.

(Tib.) las las ’jig rten sna tshogs skye/ de ni sems pa dang des byas/ sems pa yid kyi las yin no/ des bskyed lus dang ngag gi las/

Vasubandhu elaborates the second part of this verse in Autocommentary (Gretil. 192.5–12, Derge 166A):

Suppose you ask further what that karmic impulse is. It is “an urge and that which is made (to arise) by it.” As it says in a sutra, “There are two (kinds of) karmic impulses: an inciting karmic impulse and an incited one.” That which is an incited one is made (to arise) by an inciting one. These two (when divided) become three (types of) karmic impulses – karmic impulses of the body, speech and the mind.

(Skt.) kiṃ punastatkarmetyāha / cetanā tatkṛtaṃ ca tat / sūtra uktaṃ "dve karmaṇī cetanā karma cetayitvā ce"ti / yattaccetayitvā cetanākṛṭaṃ ca tat / te ete dve karmaṇī trīṇi bhavanti / kāyavāṅmanaskarmāṇi /

(Tib.) /las de yang gang zhig ce na/ de ni sems pa dang des byas/ /mdo las ni gnyis te/ sems pa dang bsams pa’i las so zhes gang gsungs pa la/ bsams pa gang yin pa de ni/ sems pas byas pa de yin no/ /las gnyis po de dag ni gsum yin te/ lus dang ngag dang yid kyi las rnams so/

Sthiramati elaborates in The Meaning of the Facts, An Annotated Subcommentary to (Vasubandhu’s) “Autocommentary to ‘A Treasure House of Special Topics of Knowledge’” (Chos mngon-pa mdzod-kyi bshad-pa’i rgya-cher ’grel-pa don-gyi de-kho-na-nyid, Skt. Abhidharmakoṣa-bhāṣyā-ṭīkā-tattvārtha) (Derge Tengyur vol. 210, 3A):

As for “an urge and so on,” if you wonder what this is, that which is spoken of in the sutra as “an incited (one)” is explained here in this treatise (by Vasubandhu) as “that which is made (to arise) by an urge.” The meaning is that it is caused to arise (motivated) by an urge. As for “from these two (types of) karmic impulses there are three,” (the three refer to) karmic impulses of body, speech and mind.

(Tib.) /sems pa dang zhes bya ba na/ ’di ni ’di lta bu zhig tu bya’o snyam du’o/ /mdo las/ bsams par bshad pa gang yin pa de ni ’dir bstan bcos las sems par byas pa zhes bshad de| sems pas kun nas bslang ba zhes bya ba’i don to/ /gsum zhes bya ba ni sems pas byas pa’i las la rnam pa gnyis su phye ba’i phyir ro/

In A Commentary to “A Treasure House (of Special Topics of Knowledge)”: A Filigree of Abhidharma (Chos mngon-mdzod-kyi tshig-le’ur byas-pa’i ’grel-pa mngon-pa’i rgyan) (Sera Je Library ed., 294), Chim Jampeyang explains further:

As for the {collective and individual person’s} karmic impulses spoken of (in this verse by Vasubandhu, they are) an inciting karmic impulse and that which is made (to arise) by an urge – in other words, an incited karmic impulse caused to arise (motivated) by it. Out of the two (types of) karmic impulses, an inciting karmic impulse is one that is congruent with mental cognition. {It causes the mind to move to an object} because it is the mental factor that affects the karmic impulses of the body and speech. It is a mental karmic impulse, and “mind” here is the mind that is a cognitive stimulator.

(Tib.) smras pa {thun mongs dang so so’i} las de ni sems pa’i las dang sems pa des byas pa {ste des kun nas bslang ba} bsam pa’i las gnyis las sems pa’i las ni yid shes dang mtshungs ldan {yid yul la g.yo bar byed pa} lus ngag gi las mngon par ’du byed pa’i sems byung yin pa’i phyir/ yid kyi las yin no/ yid ni ’dir skye mched kyi yid yin no/

A “cognitive stimulator” (skye-mched, Skt. āyatana) is a phenomenon that acts as a focal condition (dmigs-rkyen, Skt. ālaṃbanapratyaya) or a dominating condition (bdag-rkyen, Skt. adhipatipratyaya) for a cognition to arise. It includes the six types of cognitive objects (the focal conditions) and the six types of cognitive sensors (dbang-po, Skt. indriya) (the dominating conditions). The mind that is a cognitive stimulator refers to a mind-sensor.

A “mind-sensor” (yid-kyi dbang-po, Skt. mana-indriya) is any of the six types of consciousness (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, or mind consciousness) in the moment immediately preceding a cognition.

In the above cited verse (Treasure House IV.1), Vasubandhu does not use the Sanskrit compound manaskarma, a mind impulse, but rather the phrase manasam karma, a mental impulse. Manasam, mental, is an adjective derived from the noun manas, mind. By using the adjectival form of “mind,” Vasubandhu is restricting his more commonly used term manaskarma, “mind karma,” to mean “a karmic impulse that is a type of mind.”

When Chim Jampeyang glosses Vasubandhu’s phrase “mental karmic impulse” with “mind here is the mind that is a cognitive stimulator,” he is limiting a mind-sensor to only the mental consciousness in the karmic action of the mind driven by an inciting urge. This mental consciousness in that karmic action of the mind is an antecedent cause for the arising of the incited karmic impulses (the revealing and nonrevealing forms) in a subsequent karmic action of the body or speech. Because of that, this mental consciousness could be said to be a mind-sensor that is an immediately preceding condition for the arising of the sensory consciousness that is driving the karmic action of the body or speech containing the incited karmic impulse – although perhaps not in the exactly immediate moment of cognition.

Differentiating the Three Types of Karmic Impulse

In the Sautrantika system, all exertional impulses are included as true origins of suffering and thus are karmic. This includes the exertional urges that drive both karmic actions of the mind and karmic actions of the body and speech. Although Vaibhashika does not use the term “exertional impulse,” we have applied it to the Vaibhashika presentation in order to highlight the difference between its assertions and those of Sautrantika regarding karmic impulses, as well as to differentiate such urges from the urges that affect the consciousness and accompanying mental factors in the cognition of an object. But the question naturally arises as to why the Fourth Buddhist Council, when codifying the Vaibhashika tenets concerning abhidharma, soundly rejected the Sautrantika view of the topic, especially concerning karma.

Addressing this question, the Vaibhashika masters focused on how the Sautrantika assertion that all exertional urges are karmic renders the karmic impulses in actions of the body, speech and mind as all the same type of impulse and therefore not distinguishable from one another. These masters then explained how the Vaibhashika assertion is free of this fault.

Sanghabhadra (dGe-’dun bzang-po, Skt. Saṅghabhadra), Vasubandhu’s teacher and critic, begins the discussion of how to differentiate the karmic impulses in actions of the body, speech and mind by giving three possible criteria in his Lamp for Topics of Knowledge (Skt. Abhidharmadīpa) put in verses, with an autocommentary, An Extensive Commentary to “A Lamp for Topics of Knowledge,” A Subcommentary of Light (Skt. Abhidharmadīpa-vibhāṣāprabhāvṛtti) (Gretil ed., commentary to verse 158). He gives one interpretation of these criteria whereby each criteria renders all three types of karmic impulses into only one type, with each criterion rendering the three into a different single type. He then gives the Vaibhashika interpretation of these criteria, which implicitly rejects this interpretation:

How is the classification of these three (types of karmic impulse made)? (If) from their foundation (rten, Skt. āśraya), there would be a oneness of all (three types) because of having the body as their foundation. If from their essential nature (ngo-bo-nyid, Skt. svabhāva), they would become one as a karmic impulse of speech. If from their motivator (what makes them arise) (kun-nas slong-pa, Skt. samutthāna), they would all become one as a karmic impulse of mind because of all of them being something caused to arise in the mind. But Vaibhashika says, “It is in fact by the three.”

Further, the first two of these are divided into two, two for each of the karmic impulses by themselves. How? They are delineated like this [in my Lamp for Topics of Knowledge, verse 158]:

“The former two (those classified from their foundation and from their essential nature) have revealing and nonrevealing (forms). For the karmic impulse of the body, (there are) indeed the revealing (form) of the body and the nonrevealing (form) of the body. For the karmic impulse of speech, (there are), as well, the revealing (form) of speech and the nonrevealing (form) of speech. The third karmic impulse, an urge, is a function of the mind.”

It has been said by the Bhagavan Buddha (the One Who Overcame and Gained All), “(There is) an inciting karmic impulse and an incited (one).” Further, it was said that (karmic impulses) are threefold, “(There is) a karmic impulse of the body, a karmic impulse of speech, and a karmic impulse of the mind.”

How much more can the essential nature of a karmic impulse of body be than the essential nature of the body? That which is a karmic impulse of speech is in the essential nature of speech. How can a mental impulse of the mind, which is something other than (a mental impulse) of the body, be anything other than a mental impulse of the mind?

(Skt.) kathaṃ punareṣāṃ trayāṇāṃ karmaṇāṃ vyavasthānam ? yadyāśrayataḥ, sarveṣāṃ kāyāśritatvādekatvam / svabhāvataścet, vākkarmaivaikaṃ prāptam / samutthānataścet, manaḥkarmaikaṃ prāptam / sarveṣāṃ manasotthāpitatvāt / tribhirapīti vaibhāṣikāḥ // te punarete prathame dve karmaṇī pratyekaṃ dviprabhede / katham ? tadapadiśyate, pūrve vijñaptyavijñaptī kāyakarma khalu kāyavijñaptiḥ kāyāvijñaptiśca / vākkarmāpi vāgvijñaptirvāgavijñaptiśca / tṛtīyaṃ tu karma cetanā mānasī kriyā // uktaṃ hi bhagavatā- "cetanā karma cetayitvā" / tatpunastridhoktam- "kāyakarma vākkarma manaskarma ca" iti / kiṃ svabhāvaṃ punaridaṃ kāyakarma kiṃ tāvatkāyasvabhāvam ? yathā vākkarma vāksvabhāvam, āhosvitkāyādanyadyathā manaskarma manasonyadityetadāha /

In his Autocommentary (Gretil 192, Derge 175A), Vasubandhu expands his teacher’s explanation:

How is the classification of these three (types of karmic impulse made)? It could perhaps be from their foundation, from their essential nature or from their motivator (what causes them to arise).

[1] If it is from their foundation, they (all) come down to (being) one, (namely) a karmic impulse of body, because of their all being things that have the body as their foundation (on which they occur).

[2] If it is from their essential natures, they (all) come down to (being) one, (namely) things that are karmic impulses of speech, because of their all being things in the essential nature of a karmic impulse (that comes) from a command.

[3] If it is from their motivator, all of them come down to (being) things that are karmic impulses of mind, because of their all being things that have been motivated (caused to arise) by the mind.

The Vaibhashikas, however, say that they are (set) by means of the three causes in accord with their order.

Further, out of these, an inciting karmic impulse is a karmic impulse produced from the mind and so it is known as “an inciting karmic impulse of mind.” It gives rise to karmic impulses of body and speech [revealing and nonrevealing forms]. That which an inciting karmic impulse has given rise to is called “an incited karmic impulse.” Karmic impulses of body and speech are to be known as that.

(Skt.) kathameṣāṃ karmaṇāṃ vyavasthānam, kimāśrayataḥ āhosvit svabhāvataḥ samutthānato vā, āśrayataścedekaṃ kāyakarma prāpnoti, sarveṣāṃ kāyāśritatvāt svabhāvataścedvākkarmaikaṃ prāpnoti, vacasaḥ karmasvabhāvatvāt, samutthānataścenmanaskarmaikaṃ prāpnoti, sarveṣāṃ manaḥ samutthitatvāt, yathākramaṃ tribhiḥ kāraṇaistrayāṇāmiti vaibhāṣikāḥ. tatra punaḥ cetanā mānasaṃ karma cetanā manaskarme ti veditavyam. tajjaṃ vākkāyakarmaṇī yattaccetanājanitaṃ cetayitvā karmetyuktaṃ kāyavākkarmaṇī te veditavye.

(Tib.) /las ’di dag ji ltar rnam par gzhag ci rten las sam/ ’on te ngo bo nyid las sam/ ’on te kun nas slong ba las gal te rten las yin na ni thams cad lus la brten pa’i phyir lus kyi las gcig pur ’gyur ro/ /gal te ngo bo nyid las yin na ni de dag gi las gcig pur ’gyur ro/ /gal te kun nas slong ba las yin na ni thams cad kyang yid kyi kun nas bslang ba’i phyir yid kyi las gcig pur ’gyur ro zhe na/ bye brag tu smra ba rnams na re rgyu gsum gyis go rims bzhin du gsum rnam par gzhag go zhes zer ro/ /de la/ sems pa yid kyi las yin no/ /sems pa ni yid kyi las yin no zhes bya bar rig par bya’o/ /des bskyed lus dang ngag gi las/ /sems las skyes pa gang yin pa bsams pa’i las zhes gsungs pa de dag ni lus dang ngag gi las su rig par bya’o/

In The Clarified Meaning, An Explanatory Commentary on (Vasubandhu’s) “Treasure House of Special Topics of Knowledge” (Chos mngon-pa’i mdzod kyi ’grel-bshad don-gsal-ba, Skt. Sphuṭārtha Abhidharmakośavyākhyā) (Gretil 345, Derge Tengyur vol. 143, 2A), Jinaputra Yashomitra states this Vaibhashika position clearly regarding these three criteria:

As for “by means of the three causes,” they are “from the foundation, from the essential nature and from the motivator (of the three).” As for “of the three,” they are of the karmic impulses of body, speech and mind.

[1] The one that is (a karmic impulse) from its foundation is a karmic impulse of body. In other words, (as was said), “A karmic impulse that has the body as its foundation is a karmic impulse of body.”

[2] The one that is (a karmic impulse) from its essential nature is a karmic impulse of speech. (As was said), “Speech itself is actually a karmic impulse.”

[3] The one that is (a karmic impulse) from its motivator is a karmic impulse of mind. In other words, as was said, “What the mind has motivated.” They are being determined (like this).

(Skt.) tribhiḥ kāraṇair iti. āśrayataḥ svabhāvataḥ samutthānataś ceti. trayāṇām iti. kāyavāṅmanaskarmaṇām. āśrayataḥ kāyakarma. kāyāśrayaṃ karma kāyakarmeti. svabhāvato vākkarma. vāg eva karmeti. samutthānato manaskarma. manaḥsamutthitam iti kṛtvā.

(Tib.) /rgyu gsum gyis zhes bya ba ni rten dang ngo bo nyid dang kun nas slong bas so/ /gsum zhes bya ba ni/ lus dang / ngag dang / yid kyi las rnams so/ /rten las ni lus kyi las te/ lus la rten pa’i las ni lus kyi las zhes bya’o/ /ngo bo nyid kyi las ni ngag gi las te/ ngag nyid ngag gi las zhes bya’o/ /kun nas slong ba las ni yid kyi las te/ yid kyis kun nas bslang ba’i phyir ro/

In short, Vaibhashika asserts:

- In general, all three types of karmic impulses rely on the body as the foundation on which they occur. But only the karmic impulses of the body, being the revealing and nonrevealing forms of the body, actually are aspects of the body that a karmic impulse of mind gives rise to.

- In general, all three have the essential nature of coming from a command – namely, the command of the consciousness they accompany, together with the emotion that also accompanies the consciousness, and which cause these karmic impulses to arise as (motivates them to be) destructive, constructive or unspecified. But only the karmic impulses of speech actually have the essential nature of being a command.

- All three come from motivators – as in the previous case, all three are caused to arise (motivated) by a consciousness with an accompanying emotion. But only the karmic impulses of mind are directly caused to arise (motivated) by this antecedent motivator. The karmic impulses of body and speech are indirectly caused to arise (motivated) by them, through the intermediary of a non-karmic exertional urge and an immediate motivator consciousness with an accompanying emotion.

Summary

In the Vaibhashika system:

- The mental factor of an urge may be a performer impulse or an exertional impulse

- Only an exertional impulse (exertional urge) for a karmic action of the mind is included as a true origin of suffering and is therefore a karmic impulse

- An exertional impulse (exertional urge) for a karmic action of the body or speech is not included as a true origin of suffering and is therefore a non-karmic impulse

- A karmic impulse may be an exertional urge for a karmic action of the mind or a revealing or nonrevealing form in a karmic action of the body or speech

- A karmic exertional urge may or may not be an inciting karmic impulse

- A revealing form may or may not be an incited karmic impulse.