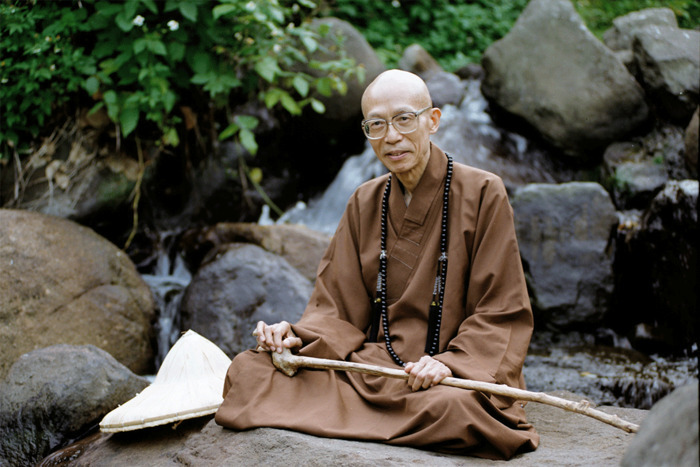

About an hour’s drive northeast of Taipei sits the home of Dharma Drum Mountain, one of Taiwan’s “Four Great Mountains,” which refers to the four most prominent Buddhist organizations in the country. Founded by the revered Chan Master Sheng Yen, who helped to ignite a renaissance of Buddhism in Taiwan, Dharma Drum Mountain has grown to become one of the most influential Buddhist organizations in modern Chinese Buddhism. I’m driving through winding mountain roads on my way to meet the new Abbot President, Venerable Guo Huei.

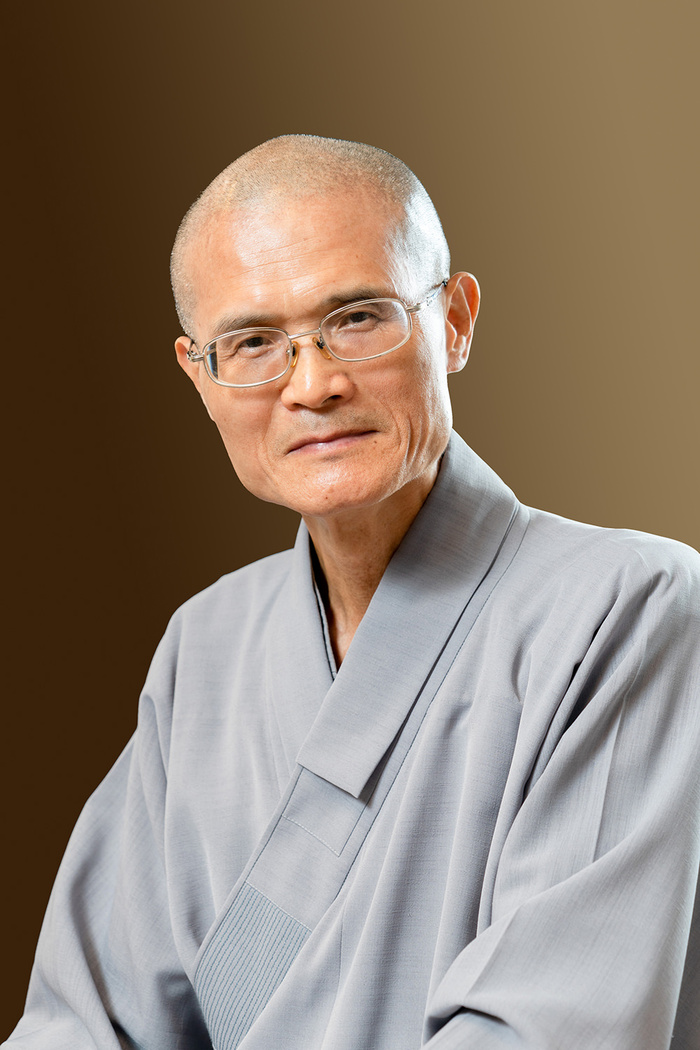

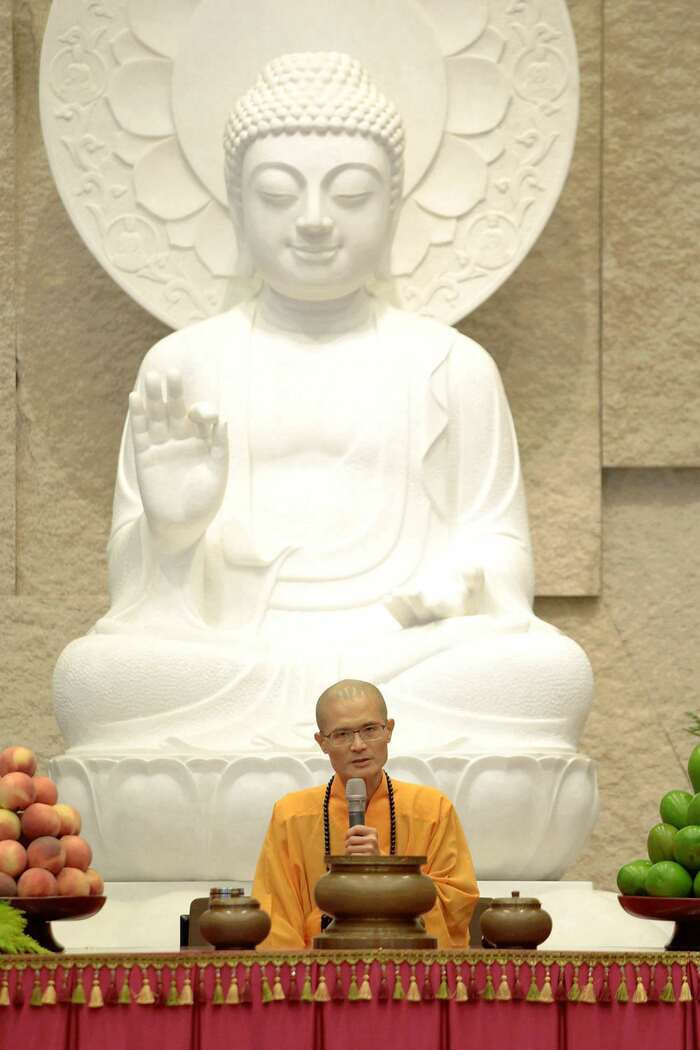

Venerable Guo Huei became ordained as a monk more than three decades ago and is now the sixth Abbot President of Dharma Drum Mountain. Holding a PhD from Japan’s Rissho University, he is carrying forward Master Sheng Yen’s legacy of promoting Chan Buddhism around the world and, in their own words, “striving to uplift the character of humanity and build a pure land on earth.” He also has responsibility for upholding Dharma Drum’s extensive academic education and social care programs. And, truth be told, I am a little nervous to meet him! But, face-to-face, Venerable Guo Huei is nothing but warm and compassionate, with the wisdom of Chan Buddhism flowing forth like nectar for the ears.

In this interview, we talk about the down-to-earth and approachable characteristics and practices of Chan Buddhism, what pure lands really are, and how we can lead a truly meaningful life.

Study Buddhism: Taiwan is predominantly a Buddhist country. Did you grow up in a religious household and always imagine that you’d end up being a monk?

Venerable Guo Huei: In the countryside of Taiwan where I was born, Buddhism was not very widespread. I joined a Buddhist society while at university, but I didn't believe in Buddhism at first, I was just interested in religion and philosophy. I was studying at National Taiwan University, which is Taiwan’s best school, and all of my classmates seemed to have their own future arrangements: either studying abroad, or finding a job, or continuing their studies in Taiwan. At that time, I wasn’t interested in any of these options. At the pre-graduation ball I wasn’t at all in the mood to dance. All I could think was, “After graduation, what should I do with my life?” Sitting outside by myself, while my friends danced inside, I recited the name of Guanyin Bodhisattva (Avalokiteshvara). After the party, on the way back home on the bus I had some sort of experience while reciting Guanyin Bodhisattva’s name. I recited until my body was gone, my body disappeared, I couldn’t feel it at all. And then there was empty space, even the bus was gone. After having this spiritual experience, I became determined to become a monk and follow this path.

You are now the Abbot President of Dharma Drum Mountain, an international Buddhist organization founded by the revered Chan Master Sheng Yen. What is Chan Buddhism and what are its unique characteristics?

Buddhism originated in India, but when it arrived in different countries and regions, it became localized. It can be said that Chinese Buddhism is the combination of Buddhism with Chinese culture. In Chinese culture, we also have Confucianism and Daoism. Confucianism attaches great importance to how it can benefit the present world and likewise in Chan practice, we don’t talk much about the past or the future, but rather we focus on the present, and how it can be helpful for our body and mind now.

The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch (known in Chinese as the Liuzu Tanjing) tells us, “The Dharma exists in the world, enlightenment is not apart from the world. To search for Bodhi apart from the world, is like looking for horns on a rabbit.” Therefore, Chan Buddhism values the fact that each of us can apply the Buddha’s compassion and wisdom to help ourselves and, at the same time, to help others. This is a very useful concept and method of practice. To help yourself, you need to use wisdom. To help others, you need to use compassion.

So how can we help ourselves? How can we have emotional balance? Through the basic Buddhist practice called the “four foundations of mindfulness.” How? Anytime, anywhere, we stay aware of our body and its condition. We observe what kinds of feelings we have at any time, wherever we are. And we can go even further and look more closely at our mind. The Study Buddhism website also advocates emotional balance, finding stability in our emotions, which is incredibly important. Emotional balance helps us to stabilize our body and mind so that we don’t end up always using the left side of our brain which tends to be competitive. The right side of our brain is more sensitive, allowing us to share our lives with the power of sensitivity, instead of always competing, wanting more property, wanting more wealth, wanting more fame and fortune.

Through meditation, we can relax, and we can also bring others happiness, so meditation is extremely beneficial. The basic methods of practice are also easy, such as simply being relaxed wherever we are. The next step is to feel your breath as you breathe, just to know where your breath is. Master Sheng Yen would say, “As long as you still have one breath, it is life’s greatest happiness.” Our existence is because of the existence of causes and conditions. As Buddhism tells us, there is no independent “I” that exists inherently, everything comes from the relationship between causes and conditions. So, even one minute of our existence is supported by innumerable causes and conditions. Therefore, we should feel thankful and enjoy our human life. On the other hand, we need to experience our human life and question what is ultimately the self? Then, we can let go of many of the external things, like wealth, fame, status, and property, because this is the external world. It is our inner world that is most important.

Therefore, by applying the Dharma, using Chan Buddhism, we can stay present wherever we are, at whatever time of the day. We can enjoy the present and relax in the present moment. We can focus on the breath and enjoy our breathing. Or we can use the method of recitation of the name of the Buddha. For example, in Chinese Buddhism, we can recite the name of Guanyin Bodhisattva or Amitabha Buddha, which helps to keep our mind stable and calm. After calming down, we can focus our mind from the external world to the internal world and, in this way, we can return our body and mind to a stable state away from its usual competitive, struggling state. Then we’ll be able to examine where our innermost, intrinsic value is and how we can use it to help ourselves and to help others, without just following the flow of the waves.

Similarly, could you tell us what Pure Land Buddhism is all about, and what its relationship to Chan Buddhism is?

Chan and Pure Land can be said to be two major characteristics of Chinese Buddhism. We can see Chan and Pure Land as two major representative schools.

The whole concept of “pure land” is actually a kind of vow. Bodhisattvas and Buddhas made vows to actualize their pure lands. We can use the modern example of a company. For instance, a good company is set up by a boss, recruiting employees for work. They’ll produce and manufacture goods that serve everyone. The same is true of pure lands. They come about from the vows of the Buddhas and the Bodhisattvas to create such a place, allowing everyone to come and engage in practice.

Therefore, one idea of pure lands is that we can use aspirations to achieve one and to allow everyone to come together to engage in practice. We believe that there are Buddhas’ pure lands in the ten directions of the universe. Dharma Drum Mountain also promotes the idea of a pure land on earth. Still, Buddhas’ pure lands enable people to practice in a more conducive place after they pass away and are reborn there. This is something we can imagine, and we can make an analogy.

For example, Dharma Drum Mountain was established in 1989. Before that, there was actually no Dharma Drum Mountain. This whole piece of land was desolate. After more than a decade of construction — it took 16 years in the end — the campus was completed and opened in 2005, and now we have this place of practice where we can organize activities to purify human minds. Isn’t this representative of a pure land on earth?

Similarly, in this world that we call Jambudvipa, through practice and through a common aspiration, we can create a better world for people to practice the Dharma. Thus, the meaning of pure land is to achieve a place for people to jointly engage in practice.

Some people make great wishes, just like the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas made great vows to help more people to practice. In the shravaka and pratekyabuddha vehicles, the focus is on practicing by oneself, it’s not necessary to have a place. Pure land practice emphasizes the place, not just about focusing on one’s inner world, but also about creating a place where everyone can come together to practice.

It’s very interesting to hear of this idea of creating a pure land on earth, a place where people can come to practice the Dharma here and now. So now that Dharma Drum Mountain has this beautiful location here in Taiwan and many others across the globe, what kinds of practices do students engage in?

Dharma Drum Mountain advocates the idea of a “pure land on earth,” using modern language, and concepts instead of using profound Buddhist terms that many would find hard to understand. The Buddhadharma can be used in everyone’s daily life. It helps to enhance people’s character in society as a whole as an effort to build a “pure land on earth.”

We have a number of practices that build character. Following Master Sheng Yen, we use the “Four Ways to Cultivate Blessings,” which are recognizing our blessings, cherishing our blessings, nurturing blessings, and sowing the seeds of blessings. We also have the “Four Practices for Helping Oneself and Others”: gratitude, thankfulness, transformation, and inspiration. Then we have the “Four Guidelines for Dealing with Desires,” which are need, can have, want, should have. There’s also the very useful “Four Steps for Handling a Problem,” which means to face problems, accept them, deal with them, and then let them go. We have the “Four Fields for Cultivating Peace,” which are a peaceful mind, peaceful body, peaceful family, and peaceful activity. These are all very easy Buddhist practices that can be used by many people everywhere.

For example, let’s take the “Four Steps for Handling a Problem”: face it, accept it, deal with it, let it go. It’s very useful! Our society is very competitive and fierce. If we can distinguish between what we can do and what we can’t do, it doesn’t matter whether it’s good or bad, we need to accept it, as we all live in this environment together, no one can escape it. But we can distinguish between what we’re able to do and what we’re not able to do. We are still alive, we are still breathing, so we can still improve ourselves and help others.

You just mentioned about a practice to cultivate blessings. I think a lot of people misunderstand blessings, as though there is some external figure bestowing gifts upon us whenever we pray or meditate! What does blessing mean in the Buddhist context?

In Chinese, the word that we use for blessings actually means “gratitude.” Buddhism is a religion of graciousness, gratitude, and thankfulness, and so our basic attitude towards the world we live in can be said to be one of “kindness and compassion have no enemies.” Anyone and everyone is the beneficiary of our compassion. Because we have gone through many lives over many eons, many people have helped us. Even without many lives and many eons, even in this one life, so many people have helped us.

So, our basic attitude is to have a mind of gratitude, a mind of gratefulness, which itself will give us a sense of happiness. For instance, you’ve come here today to interview me, and because your website is doing meritorious work, by doing this interview, we can provide some benefit to people. So, I want to thank you for this interview!

The Fivefold Spiritual Renaissance Campaign proposed by Master Sheng Yen includes the “Four Ways to Cultivate Blessings.” These are recognizing our blessings, cherishing our blessings, nurturing blessings, and sowing the seeds of blessings. We have to know that all of us are blessed. If we were not blessed, then there’s no way we could be born as humans!

Among beings, not everyone is born with a human life, there are animals, and some are born as ants. Buddhism believes that there are six realms of existence. Apart from the human realm, there are animals, hungry ghosts, and the hell and asura realms. Therefore, the fact that you have been born a human means that you certainly have done good and kind deeds in your past lives, otherwise you simply could not appear now as a human. So being able to be grateful at all times and to repay the kindness of others, we will definitely be happy. Gratitude is so easy to practice, and it should be our basic attitude.

This is a fascinating answer. And scientific research has shown that feeling gratitude is strongly associated with greater feelings of personal happiness, so it’s such an easy way to benefit ourselves. What is the best way to benefit others?

The best way is to develop great compassion. Bodhichitta is the development of the Bodhisattva mind, and that’s what we should vow to develop. Our lives do not exist just by themselves, they exist in relation to all others, and so we don’t have any kind of independent existence. Every day, every breath, every second, we can view the world with a sympathetic mind, and we can view other beings with an empathetic mind. In this way, we can give rise to great compassion.

We can see with our own eyes that there are many poor people and many sick people. It doesn’t matter whether it’s physical illness or mental illness. Even in the modern world, technology and medicine are becoming so developed, and while many physical problems can be cured, psychological problems seem to be growing stronger all the time.

We use Buddhism to help other people, to show them compassion and empathy, to bring ourselves one step closer to developing great compassion. When we see any other person, we’ll want to help them and, in this way, we also benefit ourselves. When we’re helping others, we won’t have time to worry about our own issues. Actually, our own troubles will gradually reduce, because we’re busy helping others. This is the meaning of bodhichitta.

We can also learn to relax anytime, anywhere, and keep a smiling face. I am still training myself to smile frequently! Smiling can give others a good impression, can help others, care for others, and help prevent misfortune and pain from happening.

You just said that when we develop compassion for others, our own troubles can start to disappear. But what if we are at a stage where it is really difficult to overcome our own issues and we can barely generate compassion for ourselves?

We must remember that we ourselves are one part of everyone. So, while we have to care for others, basically, we have to start by caring for ourselves.

Before aiming for something big, first we need to focus on the small things. Our goal might be ambitious, but when we’re walking this path, we need to walk step-by-step. Step-by-step means that we need to start by helping ourselves. How can we help ourselves? By using wisdom. For instance, say that maybe we feel ugly, that we aren’t pretty. In particular, many women feel the need to wear make-up every day, or think they need to have a lot of beauty treatments. Some people think they don’t earn enough money, that their wages aren’t as high as other people’s and so feel unsatisfied and unfulfilled.

We need to use the “Four Steps for Handling a Problem” the first of which is to “face it.” That’s how I am. Even if I don’t like the way I am now, this is who I am, so I need to accept myself. Accepting oneself is to face oneself. The Buddhadharma tells us that everything changes. In fact, there is no fixed “I,” and the me that exists now is simply the creation of a variety of causes and conditions. These causes and conditions are also changing non-stop, we ourselves can cause them to change, and so we can change ourselves.

How to change oneself? Just use the ‘Four Steps,” [face it, accept it, deal with it, let it go]. We should be very clear which aspects of ourselves can be changed, and which aspects cannot. For example, you think you’re not beautiful enough. It’s not just women who think that. Many guys also think they’re not handsome enough. If you have some money, you could have some beautifying treatments and change your appearance for the better. Of course you can. But the Buddhadharma tells us that it’s the internal aspect, how we change from within, that can make us much more beautiful. The exterior is just an appearance, and the manifestation of this appearance is actually created from our interior. Therefore, it is important to change from the inside, which can affect our external appearance.

For instance, developing and practicing compassion makes our faces beautiful, unlike make-up which is just temporary. Once you remove your make-up, your original face is still there. Internal change is the most important. However, I’m not saying that people shouldn’t wear make-up! For instance, on social occasions, men sometimes do need to dress like gentlemen and wear an elegant suit, so as to be presentable. But what we should value the most is internal change.

External things, especially beauty and ugliness, are all very subjective judgments. You might think you’re ugly, but I might think you’re beautiful or handsome. This is all subjective. There is no absolute beauty or ugliness, as the Dharma tells us, “All things are created by the mind alone.”

This is really beautiful advice. And it’s true – it’s so easy to see the beauty in people who are kind and compassion and generous. So, do you think that this is the meaning of life? Or what would you say is the real purpose of life?

The Dharma tells us that the greatest purpose of life is to be able to dedicate our life for the benefit of others. This is the greatest meaning of life, and it brings us the greatest happiness, because we won’t be preoccupied with our own self-interests or problems. The main aim of life is to help others and to reduce self-grasping. In fact, if we do this, we ourselves will benefit the most, because we can attain great wisdom, the great perfect mirror-like wisdom, the wisdom of the Bodhisattvas and the omniscient wisdom of the Buddhas.

The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch tells us, “The body is like a Bodhi tree, the mind like a mirror stand, I constantly wipe it, so it doesn’t become covered with dust.” We can say that this represents a gradual approach to practice. We can gradually help ourselves more and more, and gradually help others more and more too.

The other is the “sudden approach,” which the Sixth Patriarch Huineng himself practiced. He said, “The Bodhi has no tree, the mirror also has no stand, there are no objects, so nothing can become dusty.” This represents the sudden approach to practice. We can contemplate that when we help other people, there are actually no other people being helped. That’s because while there is form, everything is impermanent and in the nature of no-self or non-ego. Helping other people is the practice of all the Bodhisattvas, and seeing that ultimately there are no objects of our help forms a kind of wisdom.

By reducing our grasping, by reducing our self-attachment, we can develop wisdom. Helping others represents the Bodhisattva mind, bodhichitta, and it helps us to achieve the Buddhas’ pure lands. Like this, one will be able to help many more people. If we haven’t developed the Bodhisattva mind and just work to benefit ourselves, the results of our practice will be very, very small and limited. It’s like a small little lamp compared to the sun. They’re both forms of light, their quality of being light is the same, but it’s the quantity and the brightness that are completely different. The meaning of developing the Bodhisattva mind is to tell us not to just be a small light bulb, but to be like the sun that sends its light everywhere.

You just mentioned the concept of no-self, which ties in with my next question. What is voidness, and why is it so easily misunderstood?

Voidness is a fundamental Buddhist teaching. In Sanskrit, it’s called śūnya or śūnyatā. The meaning of voidness isn’t that there’s nothing at all. In English, it’s generally translated as “empty,” which doesn’t really seem correct – it’s not absolute nothingness.

The meaning of voidness, as Master Sheng Yen told us, is that everything exists, but there is no self. My “ego” doesn’t exist, but everything else is there. From the Chan point of view, it’s not right to say that everything is a complete illusion, that nothing whatsoever exists at all.

Voidness means that there’s nothing to grasp at, that we shouldn’t grasp at our existence.

So, where does this voidness come from? Voidness comes from impermanence, that everything is changing, everything is in the process of constantly arising and ceasing, arising and ceasing. Furthermore, because impermanence implies no-self, then there is no self or ego in existence. That is voidness. Voidness means that we can be free, liberated, that we can attain ease and freedom in life.

Voidness represents wisdom, not nothingness. This is something that most people misunderstand. Through the law of causality, looking at the deep relationship between causes and effects, we see that all phenomena do not have independent existence. Because of the relationship between cause and effect, nothing exists independently, everything is changing moment by moment.

Modern science can actually already prove some of this. For instance, atoms, nuclei, quanta, and the cells in our human bodies are changing all the time. Therefore, there is no single thing that is permanent and unchanging. That is voidness.

Thus, everything that we see is a temporary phenomenon. We are able to see; thanks to light and shadow and color, our eyes see forms. But they don’t have substantive existence, just temporary existence. When we can understand this truth, it helps to reduce our disturbing emotions and attachments. Of course, it takes practice!

It definitely takes practice! How can we bridge a simple understanding of voidness with the actual experiencing of it?

One thing is the concept, and the other thing is needing practice, for instance through meditation. The concept is knowing causality and then, with a compassionate mind, reducing our disturbing emotions and, with our cultivation of karmic merit, we reap the reward of practice where we can experience empirically what voidness actually is. So, what voidness really represents is the most important Buddhist idea – wisdom.

In Mahayana Buddhism, voidness is an expedient means, it is not an end. A very important function of voidness is that it allows us to have more expedient ways to help others. So, understanding voidness is not the sole purpose. Voidness enables us to be free from disturbing emotions and helps us generate greater power – that of compassion. From this mind of compassion born from voidness, we can help more people. This is a more proactive meaning of voidness.

Earlier on, you spoke about how the concept of voidness is tied in with impermanence. How does Buddhism talk about impermanence?

We can talk about impermanence from three different aspects. Firstly, we have the phenomenon of life, with birth, aging, sickness, and death. If we are born, we will most definitely die. Some people live to 100, some people might not reach 50. This is the reality of impermanence.

Secondly, in terms of physical space, or the circumstantial space in which we live in, impermanence manifests in four stages: arising, abiding, cessation, and voidness. Now, modern scientific knowledge tells us that there are countless extra-terrestrial planets, among which our planet is one, and all came into existence about several billions years ago. But one day, our planet will die and disappear. It undergoes arising, abiding, cessation, and voidness. Earth might not disappear after one or two years, it might take millions of years, but one day it will definitely die. Thus, because of impermanence, our planet Earth will die, it will evaporate into nothingness.

Thirdly, on a more subtle level of the mind, our thoughts are constantly arising and ceasing whenever and wherever we go. A thought arises and my mind immediately changes. Right now, we think, “Yes!” And the next moment we think, “No!” Change happens very quickly. Especially with friendship circles, or boyfriends and girlfriends, we change our minds. Change happens very swiftly!

So, our thoughts are changing all the time and wherever we are. Most people can’t really see it, but through meditation, we can see very clearly how the mind is constantly changing, always transforming. By observing this process of change, we can perform a kind of introspection. When we see that we have destructive thoughts, we can work to reduce them, and we can try to cultivate beneficial, wholesome thoughts, like compassion and wisdom. Unwholesome or destructive thoughts indicate that we have too much desire. The desire that fulfills basic needs is fine, but when we have too many wants, it brings us a lot of trouble.

So, all of this change is impermanence. The most subtle and minute form of impermanence is that of the mind’s constant changing. Therefore, the Buddha taught us that perception is suffering. The meaning of suffering here isn’t a negative pessimism, it’s just a judgment of value. Because everything is changing, you can never grasp or catch hold of any specific thing, and so the result is that we definitely suffer. Suffering doesn’t mean that eating ice cream is suffering. That’s not what it means! We’re eating something sweet, and you can’t say that it is suffering! But the Buddha’s teachings tell us that even if we eat until we’re full, we still need to eat again for the next meal; there is no such thing as a perfectly fulfilling meal. That is impermanence.

By contemplating one’s mind as impermanent, as constantly changing, we can begin to control our minds, to be the driver of our minds, so that it doesn’t just run around everywhere. To be in control of one’s own mind is the happiest state. When our mind runs amok outside, in Chinese we have a saying that goes, “Unable to find home, because of wandering around everywhere.” But happiness is at home when we find the home of our mind. When our mind runs around outside, it may be windy and rainy out there, there are a lot of dangers! Finding one’s home is the safest and happiest state. This is contemplating one’s mind as impermanent.

And finally, we can contemplate all phenomena as without a self. To understand this, one needs to really understand the Dharma, the law of cause and effect, as well as causes and conditions. Ultimately, we will know that everything really is empty of inherent existence. Then, what is there to be afraid of, and what is there to be attached to? The Heart Sutra tells us, “There is no fear, having transcended all illusions,” and “There is no wisdom and no attainment.” Even this thing called wisdom doesn’t truly exist, so there is really nothing to grasp! This is voidness. All of our anxiety and grasping comes from this innermost grasping to our lives. Because of this self-grasping mind, we have attachment to our bodies. And then we become attached to our wealth and property, because we need money to support our bodies.

With cause and effect, is this related to karma? In the West, a lot of people see karma as some sort of punishment or reward for our actions. What would you say to that?

We believe in [yin-guo] cause and effect. In Chinese, “yin” is cause and “guo” is effect. Many people encounter situations where you do a lot of good deeds, a lot of kind acts, but then you end up with negative results. One reason is due to the karma accumulated in previous lives.

A more positive way to think is that these encounters train us to grow. Good results are great, but bad results are just a challenge that allow me to grow as a person. Therefore, the blows we receive become a kind of training, a discipline. If it’s a good situation, it’s just like taking a free ride. A bad blow is like going upstream, rather than downstream. Going downstream is very relaxing but going against the current is very hard. Although it is so hard to go upstream, it helps to train our bodies and minds to be healthier, it trains our bodies to be strong, and it trains our minds to have fortitude. So, actually, from the point of view of Chan Buddhism, all kinds of circumstances we find ourselves in are good. There is no such thing as a bad circumstance.

Therefore, when we encounter bad things, we should regard them as a kind of training or exercise, not necessarily as past-life karma. We believe in karma, but a bad situation might not necessarily be karma. In Buddhism’s view of life, we see everything as good, there’s nothing bad. When we think of it as good, then it is good. Everything comes from our mind.

As the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch says, “A true practitioner never sees the faults in the world.” Highly developed Buddhist practitioners don’t see faults in the external world, nor do they notice the mistakes of other people. The Brahmajāla Sūtra also has a saying, “Evil things for yourself, good things for others.” This means that whatever bad things there are, I will bear them myself. And all of the good things that exist, I will share them with other people. This is the way to practice the Bodhisattva’s path.

Therefore, those who practice this Bodhisattva path can use the bad things they experience as a way to help them grow and learn, to develop their wisdom, to enhance their compassion. We can say that whether an experience is good or bad, to someone practicing the Bodhisattva path and cultivating their compassion and wisdom, every experience is good.

Do you have a final message to our readers?

Because our world and our society promote competition by whatever means necessary, even leading to war, we really need more happiness, more peace, more blessings to improve the character of every single person, to improve the quality of society. This will make the world more peaceful, more at ease, more blessed, and happier. Thank you!

Venerable Guo Huei, thank you so much for your time and insight into Chan Buddhism!