[For background, see: Shamatha and Vipashyana: General Presentation. See also: Concentration Terminology]

Objects of Shamatha

Shamatha (zhi-gnas, Skt. śamatha, calm abiding) is a stilled and settled state of mind that has the accompanying mental factor (sems-byung, subsidiary awareness) of a sense of physical and mental fitness (shin-sbyangs, flexibility). This is an exhilarating feeling of fitness to be able to concentrate on anything for as long as we wish.

Shamatha is settled on an object or in a state of mind. It can be a sense object, such as the breath, or a visualized mental object, like a Buddha. In Anthology of Special Topics of Knowledge (Chos mngon-pa kun-las btus-pa, Skt. Abhidharma-samuccaya), the fourth- or fifth-century Indian master Asanga emphasizes concentrating only on a mental object.

- In following that instruction, the Gelug tradition mostly uses a visualized Buddha as the object of focus.

- The Kagyu and Sakya traditions also employ what Gelug would consider sense objects, such as paintings of Buddhas, flowers, pebbles, and so on. This does not violate Asanga’s instruction. In the non-Gelug traditions, the objects of sensory cognition are only sensibilia, such as patches of colored shapes, not decisively determined as being a “this” or a “that.” Because such patches need to be mentally constructed into a Buddha image or a flower, focus on a Buddha image or flower is exclusively with mental cognition.

Nevertheless, most meditation masters of all Tibetans traditions recommend choosing a Buddha – whether a visualized one or an actual image – since it helps with safe direction (refuge), bodhichitta, and tantra. While focusing on a Buddha, we may also focus on a Buddha’s good qualities (yon-tan). We may then accompany our focus with belief in the fact (dad-pa, “faith”) that Buddhas have these qualities, and we may pay attention to them as features that we aspire to attain ourselves.

For attaining shamatha, we may also focus on other objects, pay attention to them in other beneficial ways, and accompany our focus with other constructive emotions and attitudes. For example:

- With the four immeasurable attitudes (tshad-med bzhi), we focus progressively on ourselves, friends, strangers, and those we dislike, and we pay attention to them with equanimity, love, compassion, and then joy.

- With equalizing and exchanging our attitudes about self and others (bdag-gzhan mnyam-brje), we focus on ourselves and all others, and pay attention to everyone as being equal. Continuing our focus, we then pay attention to others with the strong caring concern that we previously reserved for ourselves, and to ourselves with the weak caring concern that we previously had for others. These are the objects of concentration that Shantideva explains in Engaging in Bodhisattva Behavior.

- With the four close placements of mindfulnesses (dran-pa nyer-bzhag bzhi), we focus on the body as unclean, feelings as suffering, mental states as impermanent, and all phenomena as lacking true identities.

- With the four noble truths, we focus on our changing aggregates in terms of true problems and true causes of problems, and on our minds in terms of true stoppings (cessations) and true paths.

Alternatively, our focus may remain unaimed at any specific object (dmigs-med). We may remain focused:

- In a state of love and compassion, unaimed at any specific being, but extending out to everyone, like sunshine emanating from the sun,

- On voidness (emptiness), unaimed in the sense of not being aimed at true existence,

- On mind (mental activity) itself, unaimed at objects of cognition as if they existed on their own.

The latter method of focusing for attaining shamatha is used in mahamudra (phyag-chen, great seal) and dzogchen (rdzogs-chen, great completeness) meditations. There are at least four major manners of meditating:

- In the Karma Kagyu tradition of mahamudra, we focus first on commonsense objects constructed from the sensibilia of each of the senses (the sight of an orange, the smell of an orange, the taste of an orange, and so on) and then on a visualized object. When we gain a stable level of concentration, we then focus with it on the mind itself, but without being aimed at the mind as an object. We do this by settling down into the mind’s natural state of bliss (bde-ba), clarity (gsal-ba), and bareness (stong-pa).

- In the Sakya tradition of mahamudra, we stare at a visual object and then focus on just the clarity aspect (gsal-ba) of the cognition, which is the aspect that is giving rise to the cognitive appearance.

- In the Gelug/Kagyu tradition of mahamudra, we focus on the superficial nature (kun-rdzob, conventional nature) of mind as the mental activity of merely giving rise to cognitive appearances and cognitively engaging with them (gsal-rig-tsam, mere clarity and awareness).

- In the Nyingma tradition of dzogchen, we settle down into the natural state in between thoughts.

Regardless of the object we choose, we need to stay with that object until we achieve shamatha, and not switch objects part way through the process.

Conducive Conditions

To practice and achieve shamatha, we need to gather six conditions conducive for it:

- A conducive place (yul).

- Little attachment – to people, friends and loved ones, food, clothing, our own bodies, affection, comfort, praise, blame, sleep, and so on.

- Contentment with the food, clothing, weather conditions, and so on that we have.

- Being rid of the busy work (’du-’dzi) of having many distracting activities, such as carrying out business and other worldly affairs, gardening, elaborate cooking, chatting with fellow practitioners, speaking on the telephone, writing letters or email, and so on.

- Pure ethical self-discipline.

- Being rid of obsessive prejudiced thoughts (rnam-rtog) about what we usually consider desirable to do, such as watching television or videos, looking at the Internet, listening to music, reading novels, reading about astrology, medicine, and so on.

In Filigree for the Mahayana Sutras (mDo-sde rgyan, Skt. Mahāyānasūtra-alaṃkāra), Maitreya gives the five qualities of the first of the above six conducive conditions (a conducive place):

- Easy availability of food and water.

- An excellent spiritual situation (gnas), having been approved and sanctified by our own spiritual mentor or by previous masters who have meditated there.

- An excellent geographic situation (sa), being secluded, quiet, distant from people who upset us, with a pleasant long-distance view of nature, no sound of running water or the ocean to mesmerize us, and a good climate.

- The excellent company of friends similarly engaged and either living nearby or practicing with us.

- The items required for a happy bonding (Skt. yoga) with the practice, namely having the full teachings and instructions for the practice and having thought about and understood them beforehand so that we are free of questions and doubts.

The Five Deterrents to Concentration

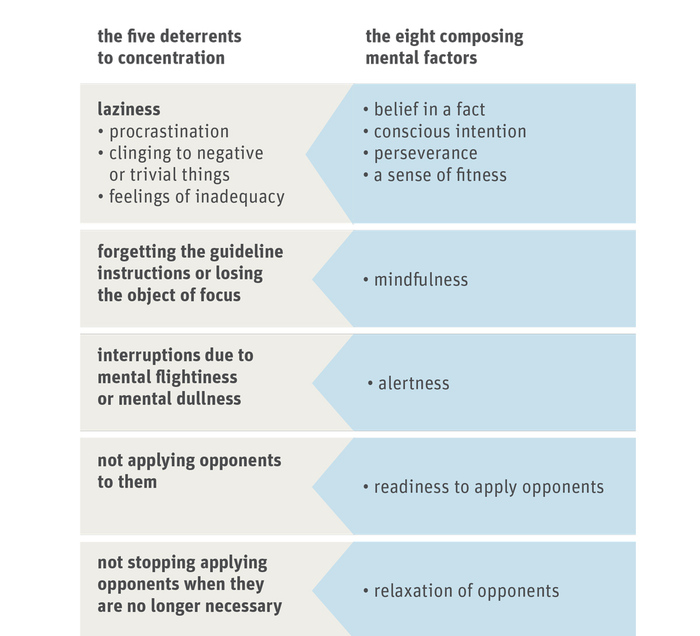

Having the full teachings and instructions for shamatha refers primarily to having detailed teachings on the five deterrents to concentration (nyes-pa lnga) and the eight composing mental factors (’du-byed brgyad) for overcoming them. Maitreya delineated these deterrents and factors in Differentiating the Middle from the Extremes (dBus-mtha’ rnam-’byed, Skt. Madhyānta-vibhaṅga).

The five deterrents to concentration are:

- Laziness (le-lo), of three types:

- Putting meditation off until later because we do not feel like doing it (sgyid-lugs),

- Clinging to negative or trivial activities or things (bya-ba ngan-zhen), such as gambling, drinking, friends who are bad influences on us, going to parties, and so on.

- Feelings of inadequacy (zhum-pa).

- Forgetting the guideline instructions or losing the object of focus (gdams-ngag brjed-pa)

- Interruptions due to mental flightiness or mental dullness (bying-rgod)

- Not applying opponents to them (’du mi-byed)

- Not stopping applying opponents when they are no longer necessary (’du-byed).

Levels of Mental Flightiness and Mental Dullness

The mental hold (’dzin-cha) on an object of focus has two aspects, mental placement (gnas-cha, mental abiding) and appearance-making (gsal-cha, clarity). The latter aspect gives rise to the cognitive appearance of the object.

Mental flightiness (rgod-pa, agitation), a subcategory of mental wandering (rnam-g.yeng) or distraction (’phro-ba), is a fault of the mental placement on the object due to desire or attachment. There are two levels:

- With gross flightiness of mind, we completely lose mental placement on the object because our mental hold on it is so weak that it is lost.

- With subtle flightiness of mind, we keep the hold, but not tightly enough, so that there is an undercurrent of thought about the object or about something else. Even if there is no undercurrent of thought, yet because the hold is slightly too tight, we feel restless and are “itching” to leave.

Mental dullness (bying-ba, sinking) is an interruption to concentration due to a fault in the appearance-making factor of the mental hold. It has three levels:

- With gross mental dullness, we lose the object because the appearance-making factor is too weak to give rise to it. This can be with or without foggy-mindedness (rmugs-pa) (heaviness of body and mind), and with or without sleepiness (gnyid).

- With middling mental dullness, we give rise to an appearance of the object, but the hold is not tight and so it lacks sharp focus (ngar).

- With subtle mental dullness, we give rise to an appearance of the object and have sharp focus, but because the mental hold is still not sufficiently tight, it is not fresh (gsar). Being “spaced out” can refer to all three levels of dullness.

The Eight Composing Mental Factors

To overcome laziness, we need to apply the first four of the eight composing mental factors:

(1) Belief in a fact (dad-pa), namely in the advantages of achieving shamatha.

(2) This leads to the conscious intention (’dun-pa) to concentrate.

(3) This leads to perseverance (brtson-’grus), making vigorous effort to do something constructive.

(4) This leads to a sense of fitness (shin-sbyangs), which gives us the flexibility to apply ourselves to the practice.

Shantideva explains four supports (dpung-bzhi) and two forces (stobs-gnyis) to enhance perseverance:

- Firm aspiration (mos-pa) – being firmly convinced of the benefits of the goal and the drawbacks of not achieving it, so that aspiration to attain it cannot be swayed

- Steadfastness (brtan) or self-confidence (nga-rgyal) – from examining if we are capable of achieving the goal and, being convinced that we are, applying ourselves steadily, even though progress goes up and down

- Joy (dga’-ba) – not being satisfied with just a little progress, but taking joy in advancing, with a sense of self-satisfaction

- Rest (dor) – taking a break when tired, but not out of laziness, in order to refresh ourselves

- Naturally accepting (lhur-len) – naturally accepting what we need to practice and what we need to rid ourselves of in order to reach our goals, and naturally to accept the hardships involved, having examined them realistically

- Taking control (dbang-sgyur) – taking control of ourselves and apply ourselves to what we wish to achieve.

To overcome forgetting the instructions or losing the object of focus, we need to apply:

(5) Mindfulness (dran-pa) – remembering, keeping the mental hold on the object of focus (dmigs-rten), like “mental glue.”

To overcome mental flightiness or mental dullness, we need to apply:

(6) Alertness (shes-bzhin) – to check the condition of our mindfulness. If the mental glue becomes undone due to gross flightiness or dullness, so that we lose the object, alertness triggers the restoring attention (chad-cing ’jug-pa’i yid-byed) to focus once more on the object. Alternatively, it triggers tightening the grip or loosening the grip of mindfulness in the case of middling and subtle dullness or subtle flightiness.

To overcome the deterrent of not applying the opponents for them, we need to apply:

(7) Readiness to apply opponents (’du-byed) – this comes from the two powers to enhance perseverance: naturally accepting what has to be done and what has to be gotten rid of, and taking control to apply ourselves.

To overcome not stopping applying opponents when they are no longer necessary, we need to apply:

(8) Relaxation of opponents (’du mi-byed) – knowing when to take a rest, knowing not to push more than is appropriate.

Concentration and Alertness as Automatic Features of Mindfulness

For achieving shamatha, we need to put our main energy on maintaining mindfulness (mental glue) on our object of focus. This means making effort primarily on holding on to the object. With mental glue, we automatically have concentration. Mental glue and concentration are merely two ways of describing the same mental activity. Mental glue describes it from the point of view of the mental hold on the object of focus; concentration describes it from the point of view of mental placement (mental abiding) on the object.

Moreover, if we liken mental glue to the sun, then alertness is like the sunlight – it is automatically present. In other words, if we are able to maintain a mental hold on an object of focus with mental glue, this implies that we are automatically keeping a check to see if the hold is proper.

Occasionally, however, we need to apply a second type of alertness, one that makes a spot check of the condition of the mental hold on the object. When doing so, however, we only use a corner of our attention, so as not to be distracted from having the main focus of our attention be on the object of the meditation.

The Nine Stages of Settling the Mind

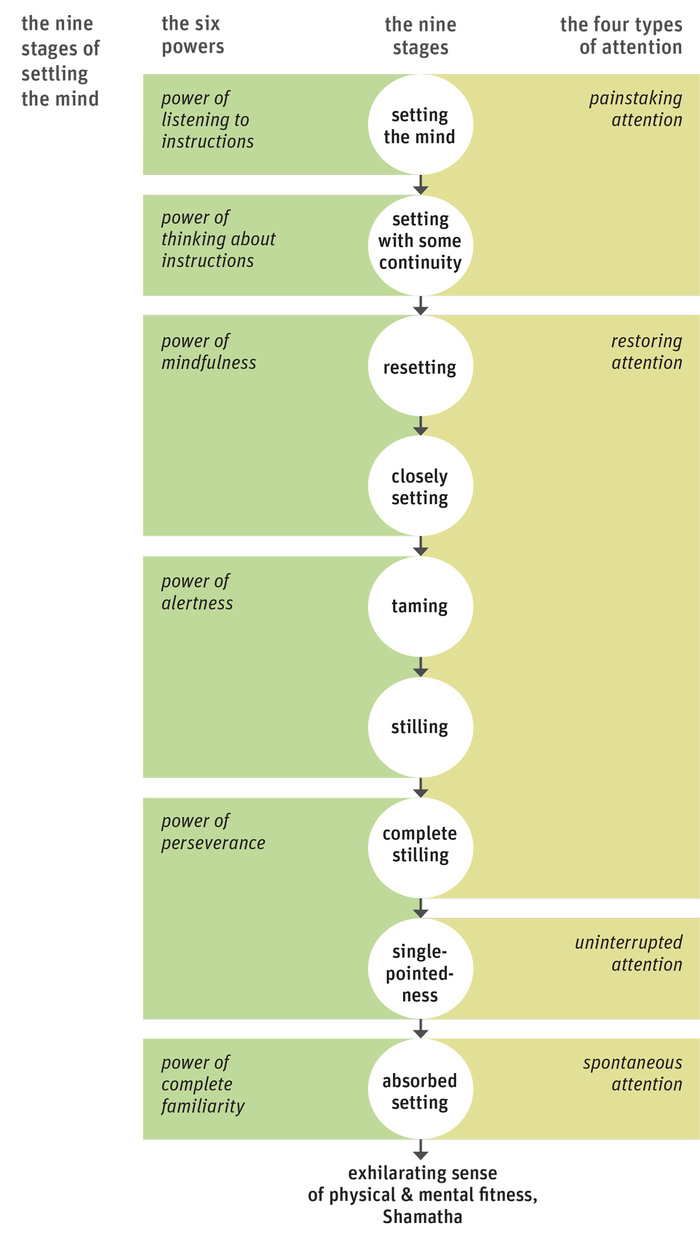

There are nine stages of settling the mind (sems-gnas dgu) into a state of shamatha:

- Setting the mind (sems ’jog-pa) on the object of focus. At this stage, we are merely able to set or place our attention on the object of focus, but are unable to maintain it.

- Setting with some continuity (rgyun-du ’jog-pa). Here, we are able to maintain our mental hold on the object with some continuity, but only for a short time before losing it. It takes some time before we recognize that we have lost the object and before we can reestablish our focus.

- Resetting (glan-te ’jog-pa). Here, we are able to recognize as soon as we have lost our mental hold on the object, and we are able to reset or restore our focus immediately.

- Closely setting (nye-bar ’jog-pa). Here, we do not lose our mental hold on the object, but because the subtle mental flightiness of an undercurrent of thought and middling dullness are strong dangers and can still occur, we need to maintain their opponents very strongly.

- Taming (dul-bar byed-pa). Here, we no longer experience gross flightiness, the subtle flightiness of an undercurrent of thought, or gross or middling dullness. However, because we have overstrained to concentrate and have sunk too deeply inwards, we have relaxed the appearance-producing factor giving rise to the appearance of the object of focus. Consequently, we experience subtle dullness. We need to refresh and uplift (gzengs-bstod) the mental hold by remembering the benefits of gaining shamatha.

- Stilling (zhi-bar byed-pa). Here, although there is no longer great danger of subtle mental dullness, nevertheless in uplifting the mind, we became too excited and the mental hold became too tight. Consequently, we experience the subtle flightiness of itchiness to leave the object of focus. We need to use strong alertness to detect this and to relax our mental hold slightly.

- Complete stilling (rnam-par zhi-bar byed-pa). Here, although the danger of subtle flightiness or dullness is minimal, we still need to exert effort to rid ourselves of them completely.

- Single-pointedness (rtse-gcig-tu byed-pa). Here, by just relying on a slight effort to apply mental glue at the beginning of the session, we are able to sustain our concentration uninterruptedly throughout the session, without experiencing any level of flightiness or dullness.

- Absorbed setting (mnyam-par ’jog-pa). Here, we are able effortlessly to maintain concentration, free of any interruptions, throughout the entire session. This is the attainment of absorbed concentration (ting-nge-’dzin, Skt. samādhi).

When, in addition to absorbed concentration, we gain the mental factor of an exhilarating sense of mental and physical fitness to concentrate perfectly on anything for as long as we wish, we gain shamatha.

The Six Powers

We gain the nine stages of settling the mind by relying on six powers (stobs-drug):

- We gain the first stage by relying on the power of listening to the instructions (thos-pa’i stobs).

- We gain the second stage by relying on the power of thinking about the instructions (bsam-pa’i stobs).

- We gain the third and fourth stages by relying on the power of mindfulness (dran-pa’i stobs).

- We gain the fifth and sixth stages by relying on the power of alertness (shes-bzhin-gyi stobs).

- We gain the seventh and eighth stages by relying on the power of perseverance (brtson-’grus-kyi stobs).

- We gain the ninth stage by relying on the power of complete familiarity (yongs-su ’dris-pa’i stobs).

The Four Types of Attention

In the process of progressing through the nine stages of settling the mind, we use four types of attention (yid-byed bzhi), which are four ways of taking the object of focus to mind:

- During the first two stages, we use painstaking attention (bsgrims-te ’jug-pa’i yid-byed), with which we use great control and force to take the object of focus to mind.

- During the third through the seventh stages, we use restoring attention (chad-cing ’jug-pa’i yid-byed), with which we repeatedly bring our focus back to the object or repair our focus if there is some fault.

- During the eighth stage, we use uninterrupted attention (chad-pa med-par ’jug-pa’i yid-byed), with which we can focus on the object without interruption.

- During the ninth stage, we use spontaneous attention (lhun-gyi ’grub-pa’i yid-byed), with which we can maintain our focus on the object effortlessly.