List of the Five Pathway Minds

There are five stages of mind developed as we progress along the spiritual path to reach liberation and enlightenment. For all practitioners, progress is in terms of these “five paths” (lam-lnga), referring to five levels of pathway minds we achieve, which lead to our goal:

- A building-up pathway mind (tshogs-lam, path of accumulation)

- An applying pathway mind (sbyor-lam, path of preparation)

- A seeing pathway mind (mthong-lam, path of seeing)

- An accustoming pathway mind (sgom-lam, path of meditation)

- A pathway mind needing no further training (mi-slob-lam, path of no more learning).

The main and most extensive explanation of the five studied in Tibetan Buddhism is that given by Maitreya in Filigree of Realizations (mNgon-rtogs rgyan, Skt. Abhisamayalamkara; Ornament of Realizations), and its Indian and Tibetan commentaries. This text presents the five pathway minds from the point of view of sutra. According to Sakya and Nyingma, the text explains the sutra path from the general Madhyamaka point of view. Within Madhyamaka, Gelug asserts that it is specifically Svatantrika-Madhyamaka and, even more specifically, Yogachara-Svatantrika-Madhyamaka.

Here, we shall outline Maitreya’s presentation, and indicate the main variations that occur among the Indian tenet systems, following primarily the Gelug presentation of them. The Indian systems include two Hinayana ones (Vaibhashika and Sautrantika) and two Mahayana (Chittamatra and Madhyamaka), and within Madhyamaka, three divisions: Sautrantika-Svatantrika, Yogachara-Svatantrika, and Prasangika. Since Gelug regards Maitreya’s text as specifically Yogachara-Svatantrika, we shall also indicate the major differences between the Panchen (Pan-chen bSod-nams grags-pa) and Jetsunpa (rJe-btsun Chos-kyi rgyal-mtshan) interpretations of this school. Neither the Jetsunpa nor the Panchen textbook tradition, however, gives a clear presentation of the Sautrantika-Svatantrika system. Therefore, for this school, we have referred to the works of Kunkyen Jamyang Zhepa (Kun-mkhyen ‘Jam-dbyangs bzhad-pa). For the Sakya and Nyingma positions, which take Maitreya’s text as representative of the Madhyamaka system in general, we shall follow Gorampa (Go-ram-pa bSod-nams seng-ge) and Mipam (Mi-pham rgya-mtsho) respectively.

I have been unable to gather the relevant information concerning the Karma, Drugpa and Drikung Kagyu presentations as given by the Eighth Karmapa, Pemakarpo (‘Brug-chen Pad-ma dkar-po) and the Single Intention (dGongs-gcig) commentaries respectively. Therefore, we shall limit our discussion to the Gelug, Sakya, and Nyingma assertions.

Occasionally, we shall also mention the Chittamatra variants concerning certain points, such as the two sets of obscuration and the stages through which each is gotten rid of. For this, we shall follow the Gelug presentation of Chittamatra.

Progressively Developing the Five Pathway Minds as a Shravaka, Pratyekabuddha, or Bodhisattva

We may progressively develop the five pathway minds on three different levels, depending on our motivation and style of practice. The first two levels are as Hinayana practitioners; the third is the Mahayana level.

Motivation (kun-slong) entails two mental factors (sems-byung, subsidiary awareness). One is the mental factor of intention (‘dun-pa) – the intention to reach a certain goal for a certain purpose. The second is the mental factor of the positive or negative emotion, such as love and compassion, or jealousy and greed, which accompanies the intention and moves us to attain a goal.

- Shravakas (nyan-thos, listeners) strive to attain liberation (thar-pa, Skt. moksha) from uncontrollably recurring rebirth (‘khor-ba, Skt. samsara, cyclic existence). Their motivating intention to reach that goal is renunciation (nges-byung) of true suffering and the true origins (true causes) of it, and the determination to be free from them. The motivating emotion is disgust (yid-byung) with their samsaric existence, filled with suffering. Listening to the teachings of a Buddha with this motivating emotion, they work to achieve their aim.

- Pratyekabuddhas (rang-rgyal, self-realizers) also strive, with renunciation and disgust with samsara, to attain liberation. They live during dark ages when the teachings of a Buddha are no longer available. They do not study with Buddhist spiritual teachers, because there are none at such times, and they teach others only subtly, through gestures, since people are not receptive. Living either singly (“like a rhinoceros”) or in small groups, they must rely on their instincts from previous lives to recall and master the Dharma.

- Bodhisattvas (byang-chub sems-dpa’) strive to achieve enlightenment, and the ability that comes with it, to be of as much benefit to all limited beings (sems-can, sentient beings) as is possible. The motivating intention to reach this goal is called “bodhichitta” (byang-sems). The motivating emotions are love (byams-pa) (the wish for everyone to have happiness and the causes for happiness), compassion (snying-rje) (the wish for everyone to be free of suffering and the causes of suffering), and an exceptional resolve (lhag-bsam) (taking responsibility to help everyone achieve these goals by attaining enlightenment).

Moreover, each of the three goals is called “bodhi” (byang-chub), a purified state. Buddhahood (enlightenment) is also called “samyaksambodhi” (yang-dag-pa rdzogs-pa’i byang-chub), the full, perfectly purified state.

The Building-up Pathway Mind

Depending on our situations and motivations, we achieve one or the other of the two Hinayana building-up pathway minds when we attain unlabored (rtsol-med) renunciation as our primary motivation in life. “Unlabored” means that this mental factor arises without needing to work ourselves up to it by relying, step by step, on a line of reasoning. We achieve a Mahayana building-up pathway mind when we attain, in addition, unlabored bodhichitta.

- According to the Gelug Jetsunpa textbooks, labored (rtsol-bcas) bodhichitta is not actually bodhichitta. The only definitional bodhichitta is the unlabored variety.

- According to the Gelug Panchen textbook tradition, both labored and unlabored bodhichittas are actually bodhichitta.

Having renunciation or both renunciation and bodhichitta as our “primary motivations in life” means that we have them manifest (mngon-gyur-ba) all the time, even when asleep. Having them manifest does not necessarily mean being conscious or attentive of them every moment from then on. Nor does it mean that we do not have other short-term motivations simultaneously, such as the motivation to go to the store to buy bread. Nevertheless, even when we are not consciously thinking about renunciation or bodhichitta, we still have the intention to achieve liberation or to achieve both liberation and enlightenment and to benefit all limited beings. We never lose that intention as the primary motivation in our lives, no matter what we do.

Further, to attain a building-up pathway mind, we need to have gained beforehand two levels of discriminating awareness (shes-rab, wisdom) of the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths:

- That which arises from hearing correct information about them (thos-byung shes-rab), so that we can focus conceptually on the sixteen through the appropriate accurate audio categories (sgra-spyi, acoustic universal), but without any associated meaning to them

- That which arises from pondering them (bsam-byung shes-rab), so that we understand and can focus conceptually on them through the appropriate accurate meaning/object categories (don-spyi, meaning universal).

Both levels of discriminating awareness are in regard to both the details of each of the sixteen aspects and the lack of an impossible soul (bdag-med, selflessness) in relation to each. The lack of an impossible soul is defined differently by each of the Hinayana and Mahayana schools of tenets (grub-mtha’).

[See: The Sixteen Aspects of the Four Noble Truths.]

The building-up pathway mind has nine stages or levels of mind – three initial, three intermediate, and three advanced. As we progress from one stage mind to the next, we “build up” first to the attainment of “shamatha” (zhi-gnas, a serenely stilled and settled state of mind, calm abiding) focused conceptually on the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths. We follow that with building up to the joined pair (zung-‘brel) of shamatha and “vipashyana” (lhag-mthong, an exceptionally perceptive state of mind, special insight) similarly focused.

- In a Hinayana context, we may focus either on the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths themselves, or on the sixteen aspects as devoid of an impossible soul of a person (gang-zag-gi bdag-med, selflessness of a person, identitylessness of a person).

- In a Mahayana context, we may focus either on the superficial truth (kun-rdzob bden-pa, conventional truth, relative truth) of the sixteen aspects or on their deepest truth (don-dam bden-pa, ultimate truth), namely on the voidness of each.

We may or may not have already achieved shamatha and vipashyana focused on some other object before attaining a first pathway mind. In fact, their attainment is not exclusively Buddhist. Non-Buddhist meditators also practice and achieve shamatha and vipashyana, but not focused on the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths. Here, when we achieve shamatha focused on the sixteen aspects, we achieve an advanced building-up pathway mind.

The Applying Pathway Mind

When we achieve the joined pair of shamatha and vipashyana focused conceptually on the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths and thus gain the discriminating awareness of the sixteen that arises from meditation (sgom-byung shes-rab), we have achieved the second pathway mind. This is an applying pathway mind. With it, we apply our joined shamatha and vipashyana in meditation so that, progressing in stages, we will eventually gain joined shamatha and vipashyana focused non-conceptually on the sixteen aspects. When we have gained that non-conceptual joined pair, we will have gained the third pathway mind – a seeing pathway mind.

With an applying pathway mind, we have achieved a conceptual joined shamatha and vipashyana focused on the sixteen aspects that does not need to rely directly, step by step, on a line of reasoning for generating decisive awareness (nges-shes) of its object. In this sense, our certitude in understanding the sixteen is unlabored, although it derives from a line of reasoning. With a building-up pathway mind, we needed to rely directly on a line of reasoning to gain the same certitude.

The applying pathway mind has four stages:

- “Heat” (drod), with which we have joined shamatha and vipashyana on the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths while awake. This stage is called “heat” since the fire of the non-conceptual discriminating awareness of a seeing pathway mind will soon be generated.

- “Peak” (rtse-mo), with which we have it even when dreaming. This stage is called “peak” since one has reached the endpoint of the stage at which the roots of our constructive force (dge-ba’i rtsa-ba, roots of virtue) are susceptible to being devastated (bcom). Before this stage, anger at a bodhisattva, for instance, can devastate the positive force (merit) we have built up. "Devastate" means that this positive force will never ripen into what it would have otherwise ripened into and that its ripening, instead, into something much weaker will be severely delayed. Such devastating disturbing emotions never arise from this stage onwards.

- “Patience” (bzod-pa), with which we have no more fears that our discriminating awareness might nullify completely any validly knowable “me.” Because of this lack of fear, this stage is called “patience.” With the attainment of this stage of pathway mind, we no longer will be reborn in any of the three worse rebirth states – as a trapped being in a joyless realm (hell being), clutching ghost (hungry ghost), or creeping creature (animal).

- “Supreme Dharma” (chos-mchog), with which we are able to apply our joined shamatha and vipashyana on the sixteen aspects to the nature of mind itself. This stage is called “supreme Dharma” since it is the highest level of ordinary beings (so-so’i skye-bo). Those who have not yet become aryas are termed “ordinary beings,” even if they have achieved one of the first two pathway minds.

Attaining a Seeing Pathway Mind and Becoming an Arya

When we achieve joined shamatha and vipashyana focused non-conceptually on the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths during our total absorption (mnyam-bzhag, meditative equipoise) on them, we attain a seeing pathway mind. Non-conceptual joined shamatha and vipashyana focused like this is called “yogic bare cognition” (rnal-‘byor mngon-sum). At this point, depending on the level of motivation with which we have been progressively developing the five pathway minds, we become aryas (‘phags-pa, highly realized beings, “noble ones”):

- Arya shravakas

- Arya pratyekabuddhas

- Arya bodhisattvas.

We continue to hold the name arya even when we have achieved the purified states that have been our goals. Thus, shravaka, pratyekabuddha, and bodhisattva arhats (Buddhas) are included among aryas.

The Two Sets of Obscuration

General Assertions

As an arya with a seeing pathway mind, we begin to have on our mental continuums true stoppings (‘gog-bden, true cessations) and true pathway minds (lam-bden, true paths) – in other words, third and fourth noble truths. The true pathway minds are our non-conceptual cognitions of the four noble truths; the true stoppings are riddances (spang-ba, abandonments) of various factors that we need to rid ourselves of in order to attain liberation and enlightenment. True pathway minds are both the causal minds that bring about true stoppings as well as the resultant minds that have these true stoppings.

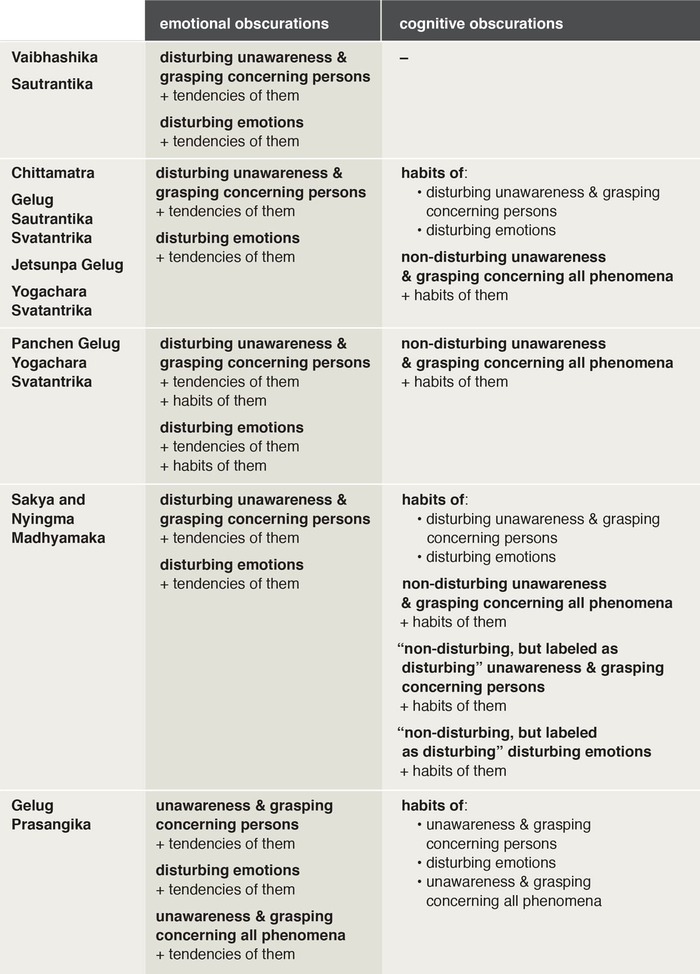

The Mahayana tenet systems classify the factors that we need to rid ourselves of two sets of obscuration (sgrib-gnyis):

- Emotional obscurations (nyon-sgrib) – obscurations that are disturbing emotions and attitudes, and which prevent liberation,

- Cognitive obscurations (shes-sgrib) – obscurations regarding all knowables, and which prevent omniscience.

The two Hinayana tenet systems do not assert the two sets of obscuration. They accept that in order to attain either liberation or enlightenment, aryas need to rid themselves of all the factors included among the emotional obscurations, but they do not call them emotional obscurations. For ease of discussion, we shall use the term emotional obscurations in reference to their presentations as well.

The two Mahayana tenet systems assert both sets of obscuration.

Each tenet system presents only one assertion concerning the items that constitute each set of obscurations. Whether they are outlining the shravaka, pratyekabuddha, or bodhisattva arya pathway minds, they specify the same sets of obscuration in reference to all three arya types. Thus, for example, it is not the case that, in any system, shravaka, pratyekabuddha, and bodhisattva aryas work on ridding themselves of differently defined sets of emotional obscuration.

Items Constituting the Emotional Obscurations

In the two Hinayana tenet systems, the emotional obscurations include (1) unawareness (ma-rig-pa, ignorance), referring to misknowing how persons exist, and its tendencies (sa-bon, seeds). This entails grasping for an impossible soul of persons (gang-zag-gi bdag-‘dzin, grasping for the self of persons), and its tendencies. (2) Disturbing emotions and attitudes (nyon-mongs, Skt. klesha, afflictive emotions), and their tendencies. For ease of discussion, we shall sometimes refer to grasping for an impossible soul of persons merely as “grasping concerning persons.” We shall always refer to disturbing emotions and attitudes merely as “disturbing emotions.”

Within Mahayana, Gelug Prasangika adds (1) unawareness is also misknowing how all phenomena exist, including persons, and its tendencies. This entails grasping for the impossible soul of all phenomena (chos-kyi bdag-‘dzin, grasping for the self of all phenomena), including persons, and its tendencies. For ease of discussion, we shall sometimes refer to grasping for an impossible soul of all phenomena merely as “grasping concerning all phenomena.”

All Mahayana tenet systems assert that the items Hinayana includes among the emotional obscurations also have habits (bag-chags, instinct, constant habit). Thus, all Mahayana tenet systems assert (1) habits of unawareness and grasping concerning persons, and (2) habits of the disturbing emotions.

- Except for Panchen Yogachara-Svatantrika, all other Mahayana systems include these habits of the emotional obscurations among the cognitive obscurations.

- Panchen Yogachara-Svatantrika includes the habits of the emotional obscurations among the emotional obscurations.

[For the finer distinctions between tendencies and habits, see: The Distinction between Tendencies and Habits: Gelug Usage.]

Definitions of Grasping for an Impossible Soul of Persons

All Hinayana and Mahayana tenet systems except Gelug Prasangika share the same assertion:

- Coarse grasping concerning persons is for persons to exist as static, monolithic souls independently of the aggregates (rtag-gcig-rang-dbang-gi bdag).

- Subtle grasping concerning persons is for persons to exist as self-sufficiently knowable souls (rang-rkya thub-‘dzin-pa’i bdag).

Gelug Prasangika asserts:

- Coarse grasping concerning persons is the same as the subtle grasping concerning persons asserted by the other schools.

- Subtle grasping concerning persons is for the existence of persons to be established by their being truly findable (bden-par grub-pa).

Disturbing and Non-disturbing Unawareness

According to abhidharma (special topics of knowledge), there are two types of defiling unawareness (kun-nas nyon-mongs-pa’i ma-rig-pa): one that is a disturbing mental state (nyon-mongs-can) and one that is a non-disturbing one (nyon-mongs-can min-pa). The former is included among the disturbing emotions, the latter is not. For ease of discussion, we shall call the former “disturbing unawareness” and the latter “non-disturbing unawareness.”

- Disturbing unawareness accompanies destructive actions and states of mind,

- Non-disturbing unawareness accompanies constructive and unspecified actions and states of mind.

This formulation implies that disturbing unawareness accompanies only destructive actions and states of mind; whereas non-disturbing unawareness accompanies not only constructive and unspecified actions and states of mind, but also destructive ones as well.

According to Vaibhashika:

- Unawareness (ma-rig-pa) is a stupefying, anti-knowing mental factor. It functions as a mental block preventing the cognition of the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths with a seeing pathway mind and nothing else. It is based on accepting the misinformation of the non-Buddhist assertions of them and is only doctrinally based. It entails only gross grasping concerning persons and is present only in destructive minds or minds thinking with a deluded outlook toward a transitory network. Although Hinayana does not assert emotional obscurations, if it did, it would be included in them.

- Non-disturbing unawareness is not knowing all the profound and extensive features of what only a Buddha knows. It does not prevent liberation, but does prevent omniscience. Vaibhashika does not specify non-disturbing unawareness as constituting a separate set of obscurations.

According to Sautrantika:

- Disturbing unawareness is misknowing the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths. It entails both gross and subtle grasping concerning persons. It underlies all disturbing emotions and is included in what would be the Hinayana equivalent of the emotional obscurations.

- Non-disturbing unawareness is asserted the same way as it is by Vaibhashika.

Chittamatra and Yogachara-Svatantrika assert disturbing unawareness as not knowing how persons exist.

Chittamatra and Gelug Svatantrika assert that non-disturbing unawareness concerns how all phenomena exist. They include the latter as a cognitive obscuration.

Sakya and Nyingma Madhyamaka agree that non-disturbing unawareness is a cognitive obscuration. However, they assert two types of non-disturbing unawareness: one concerning all phenomena and one concerning persons. The one concerning persons is a subcategory of the one concerning all phenomena. Non-disturbing unawareness concerning persons is a “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” state of mind (nyon-mongs-kyi ming-btags-pa). Based on this unawareness, these two schools also specify “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” disturbing emotions. All of these are included among the cognitive obscurations.

Sautrantika-Svatantrika and Prasangika assert unawareness as misknowing.

Gelug Prasangika does not assert non-disturbing unawareness. According to its presentation, whether unawareness concerns persons or all phenomena, it is disturbing and thus included among the emotional obscurations.

- When Gelug Prasangika uses the term “non-disturbing unawareness” and includes it among the cognitive obscurations, it refers to the factor on a mental continuum that prevents that continuum from cognizing manifestly and explicitly the two truths about any phenomenon simultaneously. This factor is not a way of cognizing anything, but rather is a noncongruent affecting variable (ldan-min ‘du-byed). Therefore, it is only called an unawareness, but is not actually an unawareness, since an unawareness is a way of cognizing something.

Items Constituting the Cognitive Obscurations

In all Mahayana systems, except Gelug Prasangika, the cognitive obscurations include (1) non-disturbing unawareness concerning how all phenomena exist, and its habits. This entails grasping concerning all phenomena and its habits.

Gelug Prasangika includes only the habits of grasping concerning all phenomena.

All Mahayana systems, except Panchen Yogachara-Svatantrika, add (1) the habits of the disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning persons, and (2) the habits of the disturbing emotions.

Sakya and Nyingma Madhyamaka further add (1) “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” unawareness and grasping concerning persons, and their habits, and (2) “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” disturbing emotions, and their habits.

Definitions of the Grasping for an Impossible Soul of All Phenomena

Chittamatra asserts two types of grasping for an impossible soul of all phenomena, both of which are subtle. It does not assert a gross level of this grasping:

- Subtle grasping for forms of physical phenomena and the ways of taking them as cognitive objects to exist as phenomena (“souls”) deriving from different natal sources (rdzas). The natal source of something is that from which it comes – for instance, an oven in relation to a loaf of bread and a seed in relation to a flower. Although this grasping is specified in terms of forms of physical phenomena, it applies to all nonstatic (impermanent) phenomena. Static phenomena do not derive from natal sources.

- Subtle grasping for phenomena to exist as “souls” having on their own sides the individual defining characteristics of the names and concepts for them, which would serve as the basis for applying specific sounds to them as names.

In Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika,

- Coarse grasping is the first form of subtle grasping asserted by Chittamatra.

- Subtle grasping is for phenomena to exist as truly unimputed “souls.”

Gelug Sautrantika-Svatantrika accepts only the subtle grasping that Yogachara-Svatantrika asserts. It does not present gross and subtle forms of this grasping.

In Sakya and Nyingma Madhyamaka grasping is for phenomena to exist (a) as truly unimputed “souls,” (b) as devoid of being truly unimputed “souls,” (c) as both, or (d) as neither. All four extremes are merely categories knowable only by conceptual cognition. The voidness (emptiness) or absence of phenomena existing as any of these four impossible “souls” is beyond words and concepts.

In Gelug Prasangika, grasping is for phenomena to exist as truly findable “souls” that are the referent objects of the names and concepts for them.

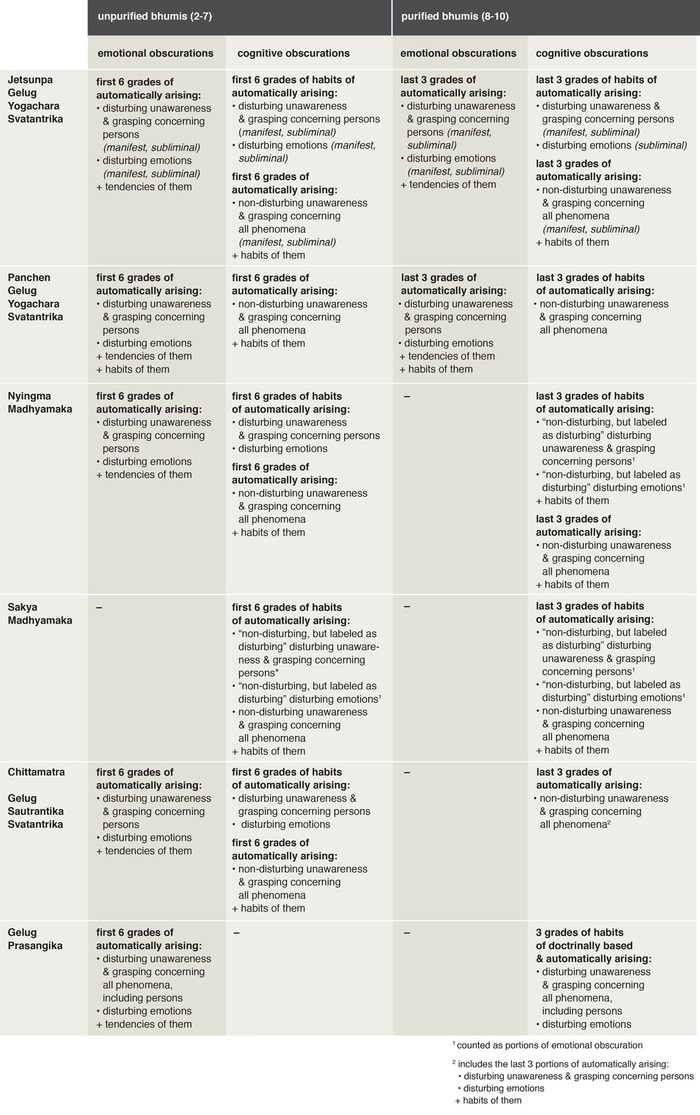

Chart of the Items Constituting the Two Sets of Obscuration

Which Arhats Are Rid of Them

According to the two Hinayana systems:

- Shravaka and pratyekabuddha arhats have rid themselves of what, in their systems, are equivalent to the emotional obscurations.

- Buddhas have additionally rid themselves of non-disturbing unawareness concerning the profound and extensive features of what only a Buddha knows.

Chittamatra, Gelug Sautrantika-Svatantrika, and Gelug Prasangika assert:

- Shravaka and pratyekabuddha arhats have rid themselves of only the emotional obscurations.

- Buddhas have rid themselves of both sets of obscuration.

According to Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika:

- Shravaka arhats have rid themselves of only the emotional obscurations.

- Pratyekabuddha arhats have also rid themselves of the gross cognitive obscurations.

- Buddhas have additionally rid themselves of the subtle cognitive obscurations.

According to Sakya Madhyamaka:

- Shravaka and pratyekabuddha arhats have rid themselves of only the emotional obscurations. However, included among the emotional obscurations are not only the gross and subtle grasping concerning persons, but also a partial aspect of grasping concerning all phenomena. That partial aspect is grasping for their five aggregates to exist only in the first of the four extreme impossible ways – as truly unimputed “souls.”

- Buddhas have additionally rid themselves of the cognitive obscurations.

According to Nyingma Madhyamaka:

- Shravaka and pratyekabuddha arhats have rid themselves of only the emotional obscurations. However, included among the emotional obscurations are not only the gross and subtle grasping concerning persons, but also a partial aspect of grasping concerning all phenomena. That partial aspect is grasping for their five aggregates to be a partless whole (phung-po-lnga ril-por ‘dzin-pa).

- Buddhas have additionally rid themselves of the cognitive obscurations.

Dormant Factors within the Obscurations

Except in Gelug Prasangika, both sets of obscuration contain both ways of being aware of something (shes-pa) and dormant factors (bag-la nyal).

- The ways of being aware of something that constitute the emotional obscurations are disturbing emotions.

- The ways of being aware of something that constitute the cognitive obscurations are non-disturbing states of mind.

- The two sets of obscuration have no common basis (gzhi-mthun, common locus). There are no phenomena that are in both sets. Thus, the cognitive obscurations do not include any disturbing emotions or attitudes.

In Gelug Prasangika, cognitive obscurations include only dormant factors.

Dormant factors are nongruent affecting variables – nonstatic abstractions that are neither forms of physical phenomena nor ways of being aware of something. Being nonstatic, they arise from causes and produce results.

- In all tenet systems, the emotional obscurations have both tendencies and habits; the cognitive obscurations have only habits.

- In all tenet systems, the dormant factors within the emotional obscurations include all tendencies. Panchen Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika also includes the habits of unawareness and grasping concerning persons and the habits of the disturbing emotions.

- Those included within the cognitive obscurations are habits.

The Hinayana tenet systems do not assert habits of obscurations.

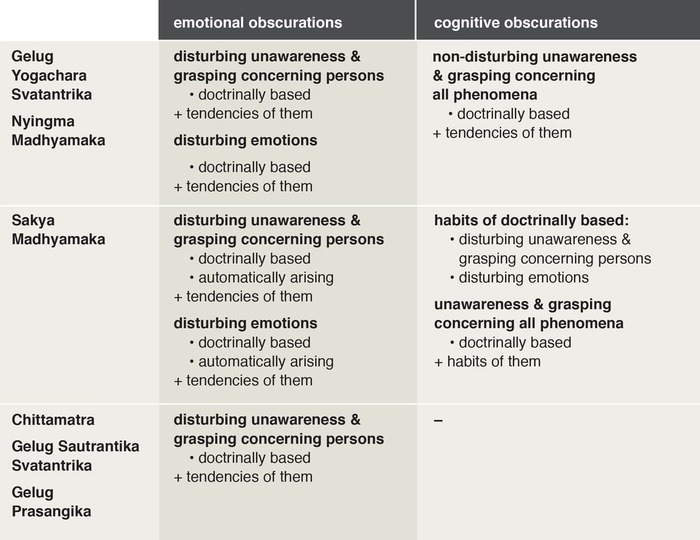

Doctrinally Based and Automatically Arising Obscurations

The ways of being aware of something in both sets of obscuration include two types: doctrinally based (kun-brtags, conceptually based) and automatically arising (lhan-skyes).

- Doctrinally based obscurations come from learning and accepting certain assertions of an incorrect non-Buddhist Indian tenet system. Gelug Prasangika asserts that they may also come from learning and accepting certain assertions of a lower Buddhist tenet system. Even if we have not studied any such tenet system in this lifetime and do not have them manifest now, everyone has dormant tendencies deriving from study in some previous life. This follows from the assertions that previous lives are without beginning, and that there was no such thing as a first time when either the non-Buddhist or Buddhist tenet systems were taught. Doctrinally based obscurations may also derive from non-Indian systems that assert the same tenets as Indian ones do, and even from our misunderstandings of correct Buddhist tenet systems.

- Automatically arising obscurations come independently of having learned and accepted any incorrect tenet system of beliefs.

- Because Gelug Prasangika asserts the cognitive obscurations as including only habits, the division of doctrinally based and automatically arising obscurations does not apply to this set in its system.

- Doctrinally based emotional obscurations have only tendencies.

- Automatically arising emotional obscurations have both tendencies and habits.

- Cognitive obscurations, both doctrinally based and automatically arising, have only habits.

What a Seeing Pathway Mind Gets Rid Of

Shravakas

Among the emotional obscurations, what shravaka seeing pathway minds get rid of (mthong-spang, abandonments of the path of seeing) are:

- In all tenet systems, the doctrinally based forms associated with minds on each of the three planes of samsaric existence (khams-gsum, three realms), and their tendencies.

- The Hinayana systems summarize the entire list of doctrinally based emotional obscurations and represents it as the three yokes (kun-sbyor gsum): (1) a doctrinally based deluded outlook toward a transitory network, (2) a doctrinally based holding of deluded morality or conduct as supreme, and (3) doctrinally based indecisive wavering. These latter two can only be doctrinally based and do not automatically arise.

The three planes of samsaric existence are:

- The plane of sensory objects of desire (‘dod-khams, desire realm)

- The plane of ethereal forms (gzugs-khams, form realm)

- The plane of formless beings (gzugs-med khams, formless realm).

The latter two are called the two higher planes of samsaric existence (khams gong-ma, higher realms). Note that these emotional obscurations associated with the two higher planes of samsaric existence are present not only in the minds of beings whose bodies and minds are both in those planes, but also in the minds of those whose bodies are on the plane of sensory objects of desire, but whose minds are on one of the two higher planes. The minds of such desire realm beings are on the higher planes of samsaric existence when they are totally absorbed in one of the four levels of mental stability (bsam-gtan, Skt. dhyāna) – the “four dhyanas” – associated with the plane of ethereal forms, or in one of the four balanced absorptions (snyoms-‘jug) associated with the plane of formless beings.

Among the cognitive obscurations, shravaka seeing pathway minds get rid of:

- In all tenet systems, nothing.

Pratyekabuddhas

Among the emotional obscurations, a pratyekabuddha seeing pathway mind gets rid of:

- In all tenet systems, the doctrinally based forms associated with minds on the three planes of samsaric existence (khams-gsum, three realms), and their tendencies.

Among the cognitive obscurations, a pratyekabuddha seeing pathway minds gets rid of:

- In Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika, the doctrinally based form of the gross obscurations, and their habits.

- In all other Mahayana tenet systems, nothing.

Bodhisattvas

Among the emotional obscurations, a bodhisattva seeing pathway mind gets rid of:

- In all Mahayana tenet systems, the doctrinally based forms associated with minds on the three planes of samsaric existence (khams-gsum, three realms), and their tendencies.

- In Sakya Madhyamaka, in addition to the doctrinally based forms associated with the three planes of samsaric existence, and their tendencies, also the automatically arising forms associated with minds on the three planes of samsaric existence, and their tendencies.

Among the cognitive obscurations, a bodhisattva seeing pathway minds gets rid of:

- In Gelug Yogachara Madhyamaka, the doctrinally based form of these obscurations, and their habits. Thus, bodhisattvas begin to rid themselves of both sets of obscuration simultaneously.

- In Sakya Madhyamaka, in addition, the habits of the automatically arising emotional obscurations.

- In Chittamatra, Gelug Sautrantika-Svatantrika and Gelug Prasangika, nothing.

The Hinayana tenet systems assert that a seeing pathway mind gets rid of 88 doctrinally based disturbing emotions:

- In association with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire, there are 36:

- Ten in relation to the first noble truth (true suffering): (1) longing desire, (2) anger, (3) arrogance, (4) unawareness concerning persons, (5) indecisive wavering, and the five deluded outlooks: (6) a deluded outlook toward a transitory network, (7) an extreme outlook, (8) holding a deluded outlook as supreme, (9) an outlook of holding deluded morality or conduct as supreme, and (10) a distorted outlook.

- Seven in relation to the second noble truth (true origins of suffering): the above ten, omitting (6) a deluded outlook toward a transitory network, (7) an extreme outlook, and (9) an outlook of holding deluded morality or conduct as supreme.

- Seven in relation to the third noble truth (true stoppings): the same seven as in relation to the second noble truth.

- Eight in relation to the fourth noble truth (true pathway minds): the same seven as in relation to the second and third noble truths, but including (9) an outlook of holding deluded morality or conduct as supreme.

- In association with minds on the planes of ethereal forms and formless beings, there are 31 for each. They include the same doctrinally based disturbing emotions as are associated with the plane of sensory objects of desire, but omitting (2) anger in relation to each of the four noble truths. Thus, there are nine in relation to the first noble truth, six in relation to the second, six in relation to the third, and seven in relation to the fourth.

All Mahayana systems assert that a seeing pathway mind gets rid of 112 doctrinally based disturbing emotions:

- In association with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire, there are 40, ten each in relation to each of the four noble truths. The ten are the same list as asserted by the Hinayana systems in relation to the first noble truth.

- In association with minds on the planes of ethereal forms and formless beings, there are 36 for each. They include the same doctrinally based disturbing emotions as are associated with the plane of sensory objects of desire, but omitting (2) anger in relation to each of the four noble truths. Thus, there are nine in relation to each of the four noble truths.

- Gelug Prasangika asserts that (4) unawareness also is concerning how all phenomena exist.

Chart for What a Bodhisattva Seeing Pathway Mind Gets Rid Of

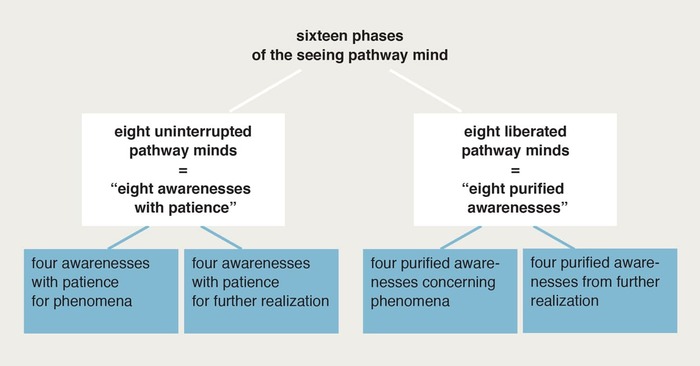

The Sixteen Phases of the Seeing Pathway Mind

Total absorption on the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths with a seeing pathway mind has sixteen phases (skad-cig, moments):

- Eight uninterrupted pathway minds (bar-chad med-lam) – pathway minds having non-conceptual cognition of the sixteen

- Eight liberated pathway minds (rnam-grol lam) – pathway minds having separations (bral-ba, partings), true stoppings, or riddances (abandonments) of what a seeing pathway mind gets rid of.

Thus, the eight uninterrupted seeing pathway minds get rid of what a seeing pathway mind gets rid of, and the eight liberated seeing pathway minds are rid of them.

The eight uninterrupted seeing pathway minds are also called the “eight awarenesses with patience” (bzod-pa brgyad). The eight liberated seeing pathway minds are also called the “eight purified awarenesses” (shes-pa brgyad).

The eight purified awarenesses include:

- The four purified awarenesses concerning phenomena (chos-shes bzhi), one each for each of the four noble truths concerning the phenomena of the plane of sensory objects of desire

- The four purified awarenesses from further realization (rjes-shes bzhi, rjes-su rtogs-pa’i shes-pa bzhi), one each for each of the four noble truths concerning the phenomena of the two higher planes of samsaric existence.

The eight awarenesses with patience are patient for achieving the eight purified awarenesses, and include:

- The four awarenesses with patience for phenomena (chos-bzod bzhi) or, more fully, the four awarenesses with patience for the purified awarenesses concerning phenomena (chos-shes-pa’i bzod-pa bzhi)

- The four awarenesses with patience for further realization (rjes-bzod bzhi) or, more fully, the four awarenesses with patience for the purified awarenesses from further realization (rjes-su rtogs-pa’i shes-pa’i bzod-pa bzhi).

The order of the sixteen phases, then, is first an uninterrupted seeing pathway mind (an awareness with patience) regarding the first noble truth in association with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire, followed by a liberated seeing pathway mind (a purified awareness) regarding the same. A similar sequence follows for the other three noble truths in association with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire, one noble truth at a time. When everything that a seeing pathway mind gets rid of associated with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire has been gotten rid of, a similar sequence follows regarding the four noble truths in association with minds on the two higher planes of samsaric existence.

The Accustoming Pathway Mind

With an accustoming pathway mind, we accustom ourselves to the non-conceptual cognition of the four noble truths that we have gained with a seeing pathway mind. In all tenet systems, from among the emotional obscurations, we rid ourselves of the automatically arising disturbing emotions and their tendencies. The only exception is Vaibhashika, which does not assert automatically arising disturbing emotions.

Vaibhashika asserts that there are 10 disturbing emotions that an accustoming pathway mind gets rid of (sgom-spang, abandonments of the path of meditation). These are the disturbing emotions that can occur either with mental cognition or sensory cognition. Unlike the disturbing emotions that a seeing pathway mind gets rid of, which can occur only with mental cognition, there is no division according to the noble truths that they are in relation to.

- In association with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire, there are four: (1) longing desire, (2) anger, (3) arrogance, and (4) unawareness concerning persons.

- In association with minds on the planes of ethereal forms and formless beings, there are three each. These are the same four as in association with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire, but omitting (2) anger.

Sautrantika asserts that there are 13, since it asserts an automatically arising deluded outlook toward a transitory network in association with minds on each of the three planes of samsaric existence.

All Mahayana tenet systems assert 16 automatically arising disturbing emotions that an accustoming pathway mind gets rid of. To the 13 that Sautrantika asserts, Mahayana adds an automatically arising extreme outlook in association with minds on each of the three planes of samsaric existence. Gelug Prasangika asserts that unawareness is also concerning how all phenomena exist.

All tenet systems, however, agree that there are nine grades of what an accustoming pathway mind gets rid of. An accustoming pathway mind gets rid of them progressively. Thus, there are different levels of accustoming pathway minds according to the number of grades of obscuration it is rid of.

What Shravaka and Pratyekabuddha Accustoming Pathway Minds Get Rid Of

Shravakas

In all tenet systems, the nine grades of what a shravaka accustoming pathway mind gets rid of are nine grades of emotional obscurations. Specifically, they are nine grades of automatically arising disturbing emotions, and their tendencies. First, a shravaka accustoming pathway mind gets rids of the nine grades of them that are associated with a mind in the plane of sensory objects of desire. Only then does it get rid of the nine grades associated with a mind in the two higher planes of samsaric existence.

In all tenet systems, a shravaka pathway mind does not get rid of any level of cognitive obscuration.

Pratyekabuddhas

In all tenet systems, a pratyekabuddha accustoming pathway mind gets rid of the same nine grades of obscurations, and through the same stages and progression, as does a shravaka accustoming pathway mind.

The cognitive obscurations also have nine grades. Among these obscurations, a pratyekabuddha accustoming pathway mind progressively gets rid of:

- In Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika, the automatically arising gross forms, and their habits. The stages and progression are exactly the same as those for getting rid of the automatically arising forms of the emotional obscurations, and their tendencies.

- In all other tenet systems, nothing.

Stream-Enterer, Once-Returner, Non-Returner, and Arhat

The division scheme of aryas into stream-enterer (rgyun-zhugs), once-returner (phyir-‘ong), non-returner (phyir mi-‘ong), and arhat (dgra-bcom) is unique to shravaka and pratyekabuddha aryas. It does not apply to arya bodhisattvas.

- Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika asserts that this division scheme applies only to shravaka aryas, since it delineates stages of ridding oneself of only emotional obscurations.

What a Hinayana accustoming pathway mind gets rid of includes nine grades of the automatically arising form of emotional obscurations associated with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire and nine grades associated with minds on the two higher planes of samsaric existence.

Each of the four arya shravaka and arya pratyekabuddha stages has an enterer (zhugs-pa) and resultant abider (‘bras-gnas) state, thus making eight enterer and resultant levels of Hinayana aryas (zhugs-gnas brgyad).

- Enterer stream-enterers attain a seeing pathway mind and aim with the eight awarenesses with patience (uninterrupted seeing pathway minds) to get rid of the doctrinally based emotional obscurations associated with minds on the three planes of samsaric existence, and their tendencies.

- Resultant abider stream-enterers have achieved the eight purified awarenesses (liberated seeing pathway minds) and are rid of all doctrinally based emotional obscurations, and their tendencies. At this stage, they still have seeing pathway minds.

- Enterer once-returners have achieved an accustoming pathway mind. Of the nine grades of automatically arising emotional obscurations associated with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire, and their tendencies, they aim to get rid of the first six grades.

- Resultant abider once-returners are rid of all six grades. Because they will attain arhatship after only one more lifetime, they are called “once-returner.” In other words, they will return with another samsaric rebirth only one more time.

- Enterer non-returners aim to get rid of the last three of the nine grades of the automatically arising emotional obscurations associated with minds on the plane of sensory objects of desire, and their tendencies.

- Resultant abider non-returners are rid of all three grades. They are called “non-returner” because they will attain arhatship in this lifetime, without returning once more with a samsaric rebirth.

- Enterer arhats aim to get rid of all nine grades of automatically arising emotion obscurations associated with minds on the two higher planes of samsaric existence, and their tendencies. They still have accustoming pathway minds.

- Resultant abider arhats get rid of all nine grades. Now, rid of all emotional obscurations, they reach their goals of either shravaka or pratyekabuddha arhatship.

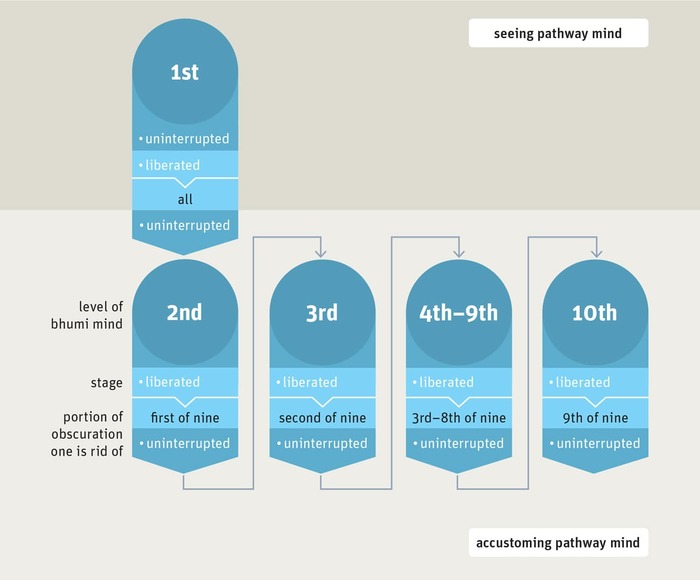

The Ten Bhumi Minds of Arya Bodhisattvas

The Mahayana seeing and accustoming pathway minds span ten “bhumis” (sa-bcu) – ten levels of arya bodhisattva minds achieved before Buddhahood. Each of the ten has an uninterrupted pathway mind and a liberated pathway mind. The Hinayana seeing and accustoming pathway minds are not divided into bhumi minds, although they too are divided into phases in which they progressively aim to get rid of a portion of something to be rid of and then progressively are rid of it.

The names of the ten bhumi mind levels are:

- Extremely joyous (rab-dga’-ba)

- Stainless (dri-med)

- Illuminating (‘od-byed-pa)

- Sparkling light (‘od-‘phro-ba)

- Difficult to cleanse (sbyang dka’-ba)

- Forward facing (mngon-du phyogs-pa)

- Far gone (ring-du song-ba)

- Immovable (mi-g.yo-ba)

- Most intelligent (legs-par blo-gros)

- Cloud of Dharma (chos-sprin).

The uninterrupted and liberated pathway minds distribute among the ten bhumi mind levels as follows:

- A first-level bhumi mind encompasses first-level uninterrupted and liberated seeing pathway minds, and a first-level uninterrupted accustoming pathway mind for achieving a second-level bhumi mind. Thus, a first-level bhumi mind encompasses the two phases of a seeing pathway mind and the first phase of an accustoming pathway mind. Only in its second phase, as a first-level liberated seeing pathway mind, is it first rid of what a seeing pathway mind is rid of. All the rest of the bhumi mind levels have only two phases and are levels of an accustoming pathway mind.

- The two phases of a second-level bhumi mind include a second-level liberated accustoming pathway mind and a second-level uninterrupted accustoming pathway mind for achieving a third-level bhumi mind. Both phases of a second-level bhumi mind are rid of the first of the nine grades of what an accustoming pathway mind is rid of.

- A third-level bhumi mind encompasses a third-level liberated accustoming pathway mind and a third-level uninterrupted accustoming pathway mind for achieving a fourth-level bhumi mind. Both phases of a third-level bhumi mind are rid of the second grade of what an accustoming path is rid of.

- The subsequent levels of bhumi minds continue in the same fashion. Thus, the two phases of a tenth-level bhumi mind include a tenth-level liberated accustoming pathway mind and a tenth-level uninterrupted accustoming pathway mind for achieving Buddhahood. Both phases of a tenth-level bhumi mind are rid of the ninth and final grade of what an accustoming pathway mind is rid of.

Chart for the Ten Bhumi Minds

The first seven-level bhumi minds are called the “unpurified bhumi minds” (ma-dag-pa’i sa), while the eighth through the tenth-level bhumi minds are the “purified bhumi minds” (dag-pa’i sa). The various tenet systems have different presentations of what “unpurified” and “purified” mean in this context, and the four Tibetan traditions differ in their explanations of several of these systems. In general, the purified bhumi minds are purified of what the unpurified bhumi minds get rid of.

What a Bodhisattva Accustoming Pathway Mind Gets Rid Of

Maitreya specified that there are nine grades of disturbing emotions that an accustoming mind gets rid of. Just as shravaka and pratyekabuddha accustoming pathway minds finish getting rid of all nine with the attainment of liberation, a bodhisattva accustoming mind finishes getting rid of them with the attainment of enlightenment. Each of the nine uninterrupted bhumi levels of mind, from the second through the tenth, rid arya bodhisattvas of one of the nine portions of what an accustoming pathway mind gets rid of. Each portion is associated with the three planes of samsaric existence all together, not one at a time. The various Mahayana tenet systems and the various interpretations of them by the different Tibetan traditions have expounded different manners in which a bodhisattva accustoming mind accomplishes this task.

In Chittamatra and Gelug Sautrantika-Svatantrika, (1) each of the six portions that the six unpurified bhumi minds get rid of is a portion of both sets of obscuration. Although this completes getting rid of the unawareness concerning persons, the disturbing emotions, and the tendencies of both, it does not complete getting rid of their habits. The habits of the emotional obscurations are included among the cognitive obscurations. Although these habits are not actually disturbing emotions or attitudes, these systems count them as grades of disturbing emotions gotten rid of by a bodhisattva accustoming mind. (2) The three purified bhumi minds, then, get rid of three portions, each of which is a portion of only the cognitive obscurations, but which include a portion of the habits of the emotional obscurations. Thus, a bodhisattva accustoming pathway mind starts to get rid of portions of both sets of obscuration simultaneously, finishes working on the side of the actual emotional obscurations first, but finishes getting rid of both sets simultaneously with the attainment of enlightenment.

In Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika, (1) each of the six portions that the six unpurified bhumi minds get rid of is also a portion of both sets of obscuration. (2) However, the three purified bhumi minds get rid of three portions, each of which is also a portion of both sets of obscuration. Thus, a bodhisattva accustoming pathway mind starts to get rid of portions of both sets of obscuration simultaneously and finishes getting rid of the complete two sets simultaneously with the attainment of enlightenment.

- According to Jetsunpa Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika, each of the items in each of the two sets of obscuration has manifest and subliminal forms. Within the emotional obscurations, the disturbing emotions and their tendencies have nine manifest and nine subliminal grades; whereas unawareness concerning persons, and its tendencies, has nine subliminal, but only six manifest grades. Similarly, within the cognitive obscurations, unawareness concerning all phenomena, and its habits, has nine subliminal, but only six manifest grades. Thus, a bodhisattva accustoming pathway mind starts to get rid of both the manifest and subliminal forms of the two sets of obscuration simultaneously. It gets rid of the manifest forms of all the cognitive obscurations before getting rid of the manifest forms of all the emotional obscurations. But, it finishes getting rid of the subliminal forms of both sets of obscuration simultaneously.

- According to Panchen Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika, each of the items of the two sets of obscuration has only manifest forms. Panchen does not assert subliminal forms of any of them. The manifest forms of the items in each of the two sets have six grades, whereas their tendencies and habits have nine grades. Thus, a bodhisattva accustoming pathway mind starts to get rid of both sets of obscuration simultaneously. It gets rid of the manifest forms of both sets of obscuration simultaneously, but before it finishes getting rid of the tendencies and habits of both sets simultaneously.

In Nyingma Madhyamaka, (1) each of the six portions that the six unpurified bhumi minds get rid of is likewise a portion of both sets of obscuration. Here, however, this completes getting rid of the emotional obscurations. Like Chittamatra and Gelug Sautrantika-Svatantrika, Nyingma Madhyamaka asserts that only the first six grades of the disturbing emotions gotten rid of by a bodhisattva accustoming pathway mind are actual disturbing emotions. Here, however, the last three grades are “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” disturbing emotions. They are included among the cognitive obscurations. (2) The three purified bhumi minds, then, get rid of three portions, each of which is a portion of the cognitive obscurations, including a portion of “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” disturbing emotions. Thus, a bodhisattva accustoming pathway mind starts to get rid of portions of both sets of obscuration simultaneously, finishes getting rid of the emotional obscurations before finishing getting rid of the cognitive obscurations, but finishes getting rid of the disturbing emotions simultaneously with the attainment of enlightenment.

In Sakya Madhyamaka, a bodhisattva seeing pathway mind gets rid of all the emotional obscurations. To satisfy Maitreya’s specification, this system asserts nine grades of “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” disturbing emotions, which are included among the cognitive obscurations. These constitute the nine grades that Maitreya specified. (1) The six unpurified bhumi minds get rid of six portions, each of which is a portion of only the cognitive obscurations, including a portion of “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” disturbing emotions. (2) The three purified level bhumi minds get rid of three portions, each of which is constituted in the same way as with the six unpurified levels. Thus, a bodhisattva accustoming mind gets rid of only the cognitive obscurations. However, it finishes getting rid of the nine grades of disturbing emotions gotten rid of by a bodhisattva accustoming mind only with the attainment of enlightenment.

[For a fuller explanation, see: Ridding Oneself of the Obscurations: Nyingma and Sakya.]

In Gelug Prasangika, (1) each of the six portions that the six unpurified bhumi minds get rid of is only a portion of the emotional obscurations. None of them get rid of portions of the cognitive obscurations. This completes getting rid of the emotional obscurations. (2) The three purified level bhumi minds get rid of three portions, each of which is only a portion of the cognitive obscurations. The cognitive obscurations, however, include the habits of the disturbing emotions. Although Prasangika accepts that there are nine portions of what an accustoming pathway mind gets rid of, it does not assert a division of the disturbing emotions into nine portions. Nevertheless, six grades of disturbing emotions and their tendencies, plus three grades of habits of the disturbing emotions makes nine grades that are finished gotten rid of only with the attainment of enlightenment.

The Items Constituting the Nine Portions of What a Bodhisattva Accustoming Pathway Mind Gets Rid Of

Simultaneously Starting and Simultaneously Finishing Getting Rid of Both Sets of Obscuration

Among those presentations in which a bodhisattva accustoming pathway mind, progressively through nine levels, starts to get rid of both sets of obscuration simultaneously and finishes getting rid of them simultaneously, each of the two sets of obscuration has nine portions that an accustoming pathway mind gets rid of, one portion from each set simultaneously at a time.

In Jetsunpa Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika:

- The nine portions of emotional obscurations gotten rid of are (1) six portions, each of which includes both manifest and subliminal automatically arising disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning persons, and their tendencies, and then three portions, each of which includes merely the subliminal variety, and their tendencies, and (2) nine portions, each of which includes both manifest and subliminal automatically arising disturbing emotions, and their tendencies.

- The nine portions of cognitive obscurations gotten rid of are (1) six portions, each of which includes a portion of both manifest and subliminal automatically arising non-disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning all phenomena, and their habits, and then three portions, each of which includes a portion of merely the subliminal variety, and their habits, (2) six portions, each of which includes a portion of the habits of both manifest and subliminal automatically arising disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning persons, and then three portions, each of which includes a portion of the habits of merely the subliminal variety, and (3) nine portions, each of which includes a portion of the habits of both manifest and subliminal automatically arising disturbing emotions.

[For the distinction between manifest and subliminal ways of being aware of something, see: Dormant Grasping for True Existence: Gelug Madhyamaka]

In Panchen Gelug Yogachara-Svatantrika:

- The nine portions of emotional obscurations gotten rid of are (1) six portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning persons, and both their tendencies and habits, and then three portions, each of which includes a portion of merely their habits, and (2) six portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising disturbing emotions, and both their tendencies and habits, and then three portions, each of which includes a portion of merely their habits.

- The nine portions of cognitive obscurations gotten rid of are (1) six portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising non-disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning all phenomena, and their habits, and then three portions, each of which includes a portion of merely their habits.

In Nyingma Madhyamaka:

- The nine portions of emotional obscurations gotten rid of are (1) six portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning persons, and its tendencies, and (2) six portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising disturbing emotions, and their tendencies.

- The nine portions of cognitive obscurations gotten rid of are (1) nine portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising non-disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning all phenomena, and their habits, (2) six portions, each of which is a portion of the habits of automatically arising unawareness and grasping concerning persons, (3) six portions, each of which is a portion of the habits of automatically arising disturbing emotions, (3) three portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” unawareness and grasping concerning persons (and counted as an emotional obscuration), and its habits, (3) three portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” disturbing emotions (and counted as an emotional obscuration), and its habits.

In Sakya Madhyamaka:

- The nine portions of cognitive obscurations gotten rid of are (1) nine portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising unawareness and grasping concerning all phenomena, and their habits, (2) nine portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” unawareness and grasping concerning persons, (which are included among the emotional obscurations), and their habits, (2) nine portions, each of which is a portion of automatically arising “non-disturbing, but labeled as disturbing” disturbing emotions (which are included among the cognitive obscurations), and their habits.

Simultaneously Starting and Consecutively Finishing Getting Rid of Both Sets of Obscuration

Among those presentations in which a bodhisattva accustoming pathway mind, progressively through nine levels, starts to get rid of both sets of obscuration simultaneously, finishes getting rid of the emotional obscurations first, but finishes getting rid of the disturbing emotions of the cognitive obscurations simultaneously:

- The nine portions that an accustoming pathway mind gets rid of are six portions, each of which contains a portion of both sets of obscuration and then three portions, each of which contains a portion of only cognitive obscurations.

- Nevertheless, since the last three portions contain, among the cognitive obscurations, a portion of the habits of the emotional obscurations, these presentations fulfill Maitreya’s specification that a accustoming pathway mind gets rid of nine portions of disturbing emotions.

- In a sense, then, this presentation of a bodhisattva accustoming mind gets rid of the actual emotional obscurations before getting rid of the cognitive obscurations, but actually finishes getting rid of the two obscurations in general simultaneously.

In Chittamatra and Gelug Sautrantika-Svatantrika:

- The six portions of emotional obscurations are gotten rid of are (1) six portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning persons, and their tendencies, and (2) six portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising disturbing emotions, and their tendencies.

- The nine portions of cognitive obscurations gotten rid of are (1) six portions, each of which include a portion of automatically arising non-disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning all phenomena, and their habits, and then three portions, each of which includes only their habits, (2) nine portions, each of which includes a portion of the habits of automatically arising disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning persons, and (3) nine portions, each of which includes a portion of the habits of the automatically arising disturbing emotions.

Finishing Getting Rid of One Set of Obscurations before Starting to Get Rid of the Other Set

Among those presentations in which a bodhisattva accustoming pathway mind, progressively through nine levels, finishes getting rid of the emotional obscurations before starting to get rid of the cognitive obscurations:

- The nine portions that an accustoming pathway mind gets rid of are six portions, each of which includes a portion of only emotional obscurations and then three portions, each of which includes a portion of only cognitive obscurations.

In Gelug Prasangika:

- The six portions of emotional obscurations gotten rid of are (1) six portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning all phenomena (including persons), and their tendencies, and (2) six portions, each of which includes a portion of automatically arising disturbing emotions, and their tendencies.

- The three portions of cognitive obscurations gotten rid are (1) three portions, each of which includes a portion of the habits of both doctrinally based and automatically arising disturbing unawareness and grasping concerning all phenomena (including persons), and (2) three portions, each of which includes a portion of the habits of both doctrinally based and automatically arising disturbing emotions.

Chart for What a Bodhisattva Accustoming Pathway Mind Gets Rid Of

A Pathway Mind Needing No Further Training

With a pathway mind needing no further training, we have reached the level of bodhi that was our aim. Progressing through the five pathway minds as Hinayana practitioners, we become either a resultant abider shravaka arhat or a resultant abider pratyekabuddha arhat, rid of the emotional obscurations.

If we have been progressing as bodhisattvas, we achieve enlightenment with a Mahayana pathway mind needing no further training and become bodhisattva arhats (Buddhas), rid of both the emotional obscurations and the cognitive obscurations.

Concerning whether Hinayana arhats eventually develop bodhichitta and achieve enlightenment:

- In Vaibhashika and Sautrantika, it is not possible.

- Within the divisions of Chittamatra, according to the Chittamatra Followers of Scriptural Authority, only some will do.

- According to Chittamatra Followers of Logic and Madhyamaka, they all eventually will do.

In those systems that assert Hinayana arhats may achieve enlightenment, shravaka and pratyekabuddha arhats who develop unlabored bodhichitta enter the bodhisattva path with their development of:

- According to Chittamatra Followers of Logic, Sakya and Nyingma Madhyamaka, and Gelug, a bodhisattva building-up pathway mind, but only provided they have also gained the discriminating awarenesses that arise from hearing and pondering a correct explanation of the voidness of all phenomena as defined individually by these systems. Although they have already gained joined shamatha and vipashyana, and can focus it conceptually on this voidness, they still need to build up sufficient positive force (bsod-nams) to gain non-conceptual cognition of it. This requires a zillion (grangs-med, countless) eons of helping others. Nevertheless, they are free of all disturbing emotions, and their tendencies.

- In Gelug Prasangika, an eighth-level bhumi mind.