Definition of “True Existence”

All Madhyamaka tenet systems assert that there is no such thing as existence established as true (bden-par grub-pa, true existence, truly established existence). When reading or hearing the translation term true existence as a convenient abbreviation for “existence established as true,” it is important not be confused by the language into thinking that it refers simply to a mode of existence. It refers to a mode of establishing (proving) that something exists. “Exists” means “exists as a validly knowable phenomenon.” Although the Sautrantika – but only according to the assertions of the Jetsunpa (rJe-btsun Chos-kyi rgyal-mtshan) textbook tradition – and Chittamatra systems assert that some existent phenomena lack true existence, Madhyamaka asserts that no validly knowable phenomenon has existence established in this impossible manner.

The Gelug tradition of Tibetan Buddhism divides Madhyamaka into Svatantrika and Prasangika, and Svatantrika into Yogachara-Svatantrika and Sautrantika-Svatantrika. The two Svatantrika divisions in common and Prasangika define true existence in two different ways.

(1) According to Svatantrika, “existence established as true” means existence established by something’s own uncommon manner of abiding on its own side, without its also being imputable there by the power of the mind projecting it. “Uncommon” means unshared with anything else. Because it is not enough that something has individual defining characteristics on its own side in combination with them being also imputable there by a conceptual mind, the lower Buddhist tenet systems assert that certain things have these defining characteristics totally independently of them being imputable.

Svatantrika, however, does assert that all phenomena have existence established by their own individual defining characteristics (rang-gi mtshan-nyid-kyis grub-pa), defined as existence established from the side of an uncommon manner of abiding that has not been merely imputed by a conceptual mind. The crucial word in this definition is “merely.” In other words, Svatantrika asserts that the existence of all validly knowable phenomena is established by individual defining characteristics findable on their own sides in combination with them being imputable (applicable) there.

(2) According to Prasangika, “existence established as true” means existence established by a manner of abiding on the side of an object, unshared with anything else, because it is not enough that defining characteristics are merely imputable (applicable). Because the lower Buddhist tenet systems believe it is not enough, they assert that certain things have them on their own sides either in combination with their being imputable there (Svatantrika) or totally independently of their being imputable there (Chittamatra and below). Thus, Prasangika considers existence established by something’s own individual defining characteristics to be existence established as true.

Regardless of definition, however, the Madhyamaka schools share a common explanation of the manner in which grasping for true existence (bden-’dzin) occurs.

Two Meanings of the Term Grasping for True Existence

The Tibetan term usually translated as “grasping for true existence,” bden-‘dzin, has two different meanings. It is used both for cognition of true existence and for cognition that something truly exists. Literally, however, it means “cognitively taking true existence (as a cognitive object).” When it is used for “cognition of true existence,” it is short for “cognitively taking as a cognitive object an appearance of true existence” (bden-snang ’dzin-pa) – in other words, merely cognizing true existence. When it is used for “cognition that something truly exists” (“grasping for true existence”), it is short for “cognitively taking as a cognitive object existence established as true” (bden-grub ’dzin-pa).

To avoid confusion, we shall translate bden-‘dzin as “cognition of true existence” when it means “cognition of an appearance of true existence.” We shall restrict the translation grasping for true existence to the second meaning of bden-‘dzin, “cognition of existence established as true.” As an umbrella term to encompass the two forms of bden-‘dzin, we shall call it “cognitively taking true existence.”

The constant habits (bag-chags) of cognitively taking true existence give rise to both types of cognitively taking true existence. When they give rise to cognizing true existence, they simultaneously give rise to appearance-making of true existence (bden-snang). The two are inseparable and merely two ways of describing one phenomenon. The constant habits also give rise to grasping for true existence. When they do, they simultaneously also give rise to appearance-making and cognition of true existence. Moreover, although consciousness in conceptual cognition as well as in non-conceptual cognition other than non-conceptual cognition of voidness always has appearance-making and cognition of true existence, only consciousness in conceptual cognition has grasping for true existence.

Both Svatantrika and Prasangika accept that the constant habits of cognitively taking true existence are included among the cognitive obscurations (shes-sgrib) that prevent omniscience. These constant habits do not stop giving rise to appearance-making and cognition of true existence until the true stopping (’gog-bden, true cessation) of this set of obscurations. That only occurs with the attainment of enlightenment. Svatantrika and Prasangika differ, however, as to when these habits stop giving rise to grasping for true existence. Svatantrika asserts that they stop doing this with enlightenment, Prasangika asserts that this happens with liberation.

- Appearance-making and cognition of true existence occur manifestly in every moment of cognition of a limited being (sentient being), except during non-conceptual total absorption (mnyam-bzhag, meditative equipoise) on the voidness of true existence. Grasping for true existence, however, occurs manifestly only during conceptual cognition. Conceptual cognition does not end until the attainment of enlightenment and not all conceptual cognition has manifest grasping for true existence. The last moment of an applying pathway mind (sbyor-lam, path of preparation) totally absorbed conceptually on voidness immediately prior to the attainment of a non-conceptual total absorption on voidness lacks manifest grasping for true existence. When arya bodhisattvas achieve the eighth of the ten levels of bhumi mind (sa, Skt. bhūmi), their conceptual cognition also lacks manifest grasping for true existence. At such times, the constant habits of cognitively taking true existence give rise merely to the appearance-making and cognition of true existence, but no longer give rise to manifest grasping for true existence.

- According to Svatantrika, grasping for true existence is included among the cognitive obscurations preventing omniscience. Therefore, they are not gotten rid of forever (spang-ba, abandoned) until the attainment of enlightenment. In the Yogachara-Svatantrika system, the attainment of liberation and enlightenment is simultaneous. In the Sautrantika-Svatantrika system, according to the Kunkyen (Kun-mkhyen ’Jam-dbyangs bzhad-pa rdo-rje II, dKon-mchog ’jigs-med dbang-po) textbook tradition, the attainment of liberation occurs before enlightenment. In the case of bodhisattvas, it occurs with the achievement of an arya bodhisattva eighth level bhumi mind.

- According to Prasangika, grasping for true existence is included among the emotional obscurations (nyon-sgrib) preventing liberation. Thus, a true stopping of grasping for true existence occurs with the attainment of liberation, and liberation is attained before enlightenment. Arya bodhisattvas attain it when they achieve the eighth of the ten bhumi-levels of mind. Shravaka arhats also attain liberation without attaining enlightenment.

The questions that need to be answered are:

- How is the continuity of grasping for true existence maintained during non-conceptual cognition, both sensory non-conceptual cognition (dbang-mngon) and non-conceptual total absorption on voidness, before attaining enlightenment according to Svatantrika, and before attaining liberation according to Prasangika?

- How is the continuity of appearance-making and cognition of true existence maintained during non-conceptual total absorption on voidness before enlightenment according to both Madhyamaka divisions in general?

Non-conceptual cognition also occurs with mental consciousness and, according to Yogachara-Svatantrika, also with cognition by reflexive awareness (rang-rig). Since the explanations of grasping for true existence during these two further types of non-conceptual cognition are the same as those for during sensory non-conceptual cognition, there is no need to discuss them separately. For ease of discussion, we shall speak only of sensory non-conceptual cognition to cover all three. We shall also restrict our discussion primarily to the Prasangika assertions.

Dormant Factors

The term dormant factor (bag-la nyal) means, literally, something that is “asleep to the taste of the mind.” They are affecting variables, associated with mental continuums, which are “lying down” and not rushing to manifest mind (consciousness).

Dormant factors include three types of nonstatic phenomena:

- subliminal awareness (bag-la nyal),

- tendencies (sa-bon, seeds),

- habits (bag-chags).

Note that the same Tibetan term, bag-la nyal, is used both as a general umbrella term for all three types, and also to signify one specific type, subliminal awareness.

Subliminal awareness is a way of knowing something (shes-pa), while tendencies and habits are noncongruent affecting variables (ldan-min ’du-byed) that are neither forms of physical phenomena nor ways of being aware of something.

[See: Types of Karmic Aftermath: Usage of Technical Terms. See also: Congruent and Noncongruent Affecting Variables]

Simultaneous Cognitions

Several cognitions, having different objects, can occur simultaneously. For example, seeing the sight of a friend talking to us occurs simultaneously with hearing the sound of his or her voice. Both cognitions are manifest (mngon-gyur-ba). Two cognitions can even be manifest simultaneously with one being non-conceptual and the other conceptual, such as seeing a friend while thinking about something else. The amount of attention (yid-la byed-pa) accompanying each manifest cognition will vary.

[See: Relationships with Objects]

- Single-minded concentration (ting-nge-’dzin) is a concentration that is free of all mental wandering, mental agitation, and mental dullness. It does not mean that it is the exclusive manifest cognition occurring at the moment. While single-mindedly concentrating conceptually on a mental image of a Buddha-figure, such as when seeing everyone as Avalokiteshvara, we can also manifestly see the body of the person whom we are viewing as this figure. However, we are not distracted, even in the slightest, by that simultaneously manifest visual non-conceptual cognition.

Subliminal cognition can also occur simultaneously with manifest ones, and often does. For example, while looking at and listening to a friend speaking to us, we may have only subliminal cognition of the physical sensation of the clothing on our bodies. In such cases, the manifest cognition is with a manifest awareness (consciousness), and the subliminal cognition is with a subliminal awareness (consciousness). They are different consciousnesses and different cognitions, not the same consciousness and not the same cognition.

To understand the difference between manifest and subliminal cognition requires understanding one of the characteristics of persons (gang-zag), individual beings with a mental continuum.

The Difference between Manifest and Subliminal Cognitions

Minds – referring specifically to mind consciousness (yid-kyi rnam-shes) – and persons (gang-zag) both cognitively take cognitive objects (’dzin-pa), uninterruptedly. Only minds, however, give rise to cognitive appearances (snang-ba) of the cognitive objects taken. A cognitive appearance is a fully transparent mental hologram (rnam-pa, mental aspect) used to represent a cognitive object in order to cognize it, even non-conceptually.

This distinction between minds and persons accords with the defining characteristics of mind (mental activity, cognition). Mind is defined as “mere clarity and awareness” (gsal-rig-tsam), which means the automatically occurring activity of simultaneously giving rise to cognitive appearances and cognitively taking them as cognitive objects, without a truly existent entity (such as a mind or person) making that happen. A person is the validly knowable “me” that is merely imputable on a functioning network of aggregates as a convention.

[See: Objects of Cognition: Gelug Presentation]

In manifest cognition, the consciousness of the manifest cognition gives rise to a mental hologram of a cognitive object, which it may explicitly apprehend. The cognitive object appears, through that hologram, both to the person and to the consciousness of the manifest cognition. Both the person and the manifest consciousness cognitively take it – both cognize or “know” it.

A manifest cognition may both explicitly and implicitly apprehend objects. Although the manifest cognition does not give rise to a mental aspect of the object that it implicitly apprehends, nevertheless the implicit apprehension is manifest. Both the manifest consciousness and the person have implicit apprehension of an object.

In subliminal cognition, the consciousness of the subliminal cognition – in other words, subliminal awareness – gives rise to a mental hologram of a cognitive object. The cognitive object appears, through that hologram, only to the consciousness of the subliminal cognition and only that consciousness cognizes it. The cognitive object of the subliminal cognition does not appear to the person and is not cognized by the person. Nor does it appear to or is it cognized by the consciousness of the manifest cognition that is simultaneously occurring and overpowering the subliminal cognition.

For example, while asleep, the sound of the alarm clock ticking appears to our ear consciousness and our ear consciousness hears it. But, it does not appear to us and we do not hear it. The ear consciousness is attentive (yid-la byed-pa) of sounds, but we are not attentive of them. If our ear consciousness were not at all attentive to sounds, it would be impossible for us to hear the sound of the alarm clock ringing.

- The subliminal cognition of the sound is a non-determining cognition of what appears to it (snang-la ma-nges-pa). Because it lacks certitude in its taking the sound as a cognitive object, the ear consciousness cannot determine that the sound is “this” and not “that.”

Subliminal cognition also occurs while we are awake. For example, while listening to music, we can have subliminal cognition of the sight of the wall in front of us. Our eye consciousness takes the sight of the wall as a cognitive object, but we do not see it. We pay no attention to it.

We can have other subliminal cognitions simultaneously with manifestly listening to music and seeing the wall only subliminally, for example, subliminal body consciousness of the sensation of the chair on which we are sitting.

- Among the five types of sensory cognition, a simultaneously occurring manifest and subliminal cognition can not be of the same sense faculty. Inattentiveness of many items or details in a field of vision and peripheral vision are not forms of subliminal cognition.

All Gelug textbook traditions accept subliminal cognition of the various types of sensory consciousness while awake and asleep. The Jetsunpa, Tendarwa (mKhas-grub bsTan-pa dar-rgyas), and Kunkyen textbook traditions also assert subliminal cognition of grasping for true existence – namely, during sensory non-conceptual cognition and non-conceptual cognition of voidness.

The Panchen (Pan-chen bSod-nams grags-pa) textbook tradition does not accept subliminal cognition of grasping for true existence.

Here, we shall restrict our discussion of subliminal cognition to the subliminal cognition of grasping for true existence and not analyze subliminal sensory cognition. Let us look first at the Panchen explanation, since it was the earlier of the two. His contemporary, Jetsunpa, formulated the other position in refutation of the Panchen position. Since their younger contemporary, Tendarwa, and, centuries later, Kunkyen accepted this alternative explanation, we shall refer to it as the Jetsunpa position.

The Panchen Position

Panchen explained that, for limited beings, during sensory non-conceptual cognition and non-conceptual total absorption on voidness, the continuity of grasping for true existence is maintained on a mental continuum merely in the form of the constant habit of cognitively taking true existence, which has always been imputable there. During non-conceptual total absorption on voidness, the continuity of appearance-making and cognition of true existence is maintained on a mental continuum also merely in the form of the constant habit of cognitively taking true existence.

During sensory non-conceptual cognition, the constant habit gives rise to manifest appearance-making and cognition of true existence. It does not give rise to grasping for true existence at all. In Svatantrika, this is also the case with the three levels of pure pathway minds (arya bodhisattva eighth, ninth, and tenth level bhumi mind) during their conceptual cognition.

During nonconceptual total absorption on voidness, the constant habit of cognitively taking true existence gives rise to neither appearance-making and cognition of true existence, nor grasping for true existence.

The Jetsunpa Objection to the Panchen Position

Jetsunpa asserts that grasping for true existence is present as an awareness without any break all the way up to, but not including, the attainment of liberation. Similarly, appearance-making and cognition of true existence as an awareness are also present, without any break, all the way up to, but not including, the attainment of enlightenment. When Panchen asserts that they are dormant in the form of the imputable constant habit of cognitively taking true existence, Jetsunpa asserts that they are dormant then as subliminal cognition.

Jetsunpa’s main objection to the Panchen position concerns the basis of imputation (gdags-gzhi) for imputing the constant habit of cognitively taking true existence during non-conceptual total absorption on voidness. Even within the context of the Prasangika assertion that tendencies and constant habits are imputed on the mere “me,” the problem is still on what is the mere “I” imputed at this time. The primary consciousness during non-conceptual total absorption on voidness is a true pathway mind (lam-bden, a noble path), a fourth noble truth. As such, it is an untainted deep awareness (zag-med ye-shes, uncontaminated wisdom) and all mental factors congruent with it would likewise be untainted. The constant habit of cognitively taking true existence is a tainted phenomenon (zag-bcas). Being tainted means it was produced by unawareness (ma-rig-pa). The deep awareness of an arya’s non-conceptual total absorption on voidness was not produced by unawareness.

A tainted phenomenon cannot be imputed on an untainted phenomenon, and doubly so when that tainted phenomenon is an “obtainer phenomenon” (nyer-len). This is the case even when the tainted phenomenon is imputed on an unspecified item (lung ma-bstan, neutral), such as on the mere “me” and that unspecified item is imputed on a tainted phenomenon. Obtainer phenomena are not only themselves tainted, but they also give rise to further tainted phenomena. It is unreasonable for something imputed on untainted deep awareness to give rise to further moments of appearance-making and cognizing true existence and to further moments of grasping for true existence. Therefore, on what tainted phenomenon present during non-conceptual total absorption on voidness are the constant habits of cognizing true existence imputed?

- Panchen asserts that no other ways of being aware of something, including bodhichitta, and not even non-revealing forms (rnam-par rig-byed ma-yin-pa’i gzugs) of vows or of karmic force are present with the mental continuum during non-conceptual total absorption on voidness. They all transform into imputed habits.

- Jetsunpa asserts that the constant habits of cognitively taking true existence are imputable on the unbroken continuity of appearance-making and cognition of true existence, whether in manifest or subliminal forms.

The Jetsunpa Position

When the subliminal cognition of grasping for true existence occurs simultaneously with a manifest cognition, the two cognitions share five congruent features (mtshungs-ldan lnga, five things in common).

According to Vasubandhu’s Treasure House of Special Topics of Knowledge (Chos mngon-pa’i mdzod, Skt. Abhidharmakośa), the five congruent features are:

- reliance (rten) – relying on the same cognitive sensor (dbang-po) as the dominating condition (bdag-rkyen) for their arising,

- object (yul) – cognitively aiming at the same focal object (dmigs-yul) as the focal condition (dmigs-rkyen, objective condition) for their arising,

- mental aspect (rnam-pa) – giving rise to the same cognitive semblance of the focal object as the aspect of the focal object cast on them and which they assume or take on,

- time (dus) – arising, abiding, and ceasing simultaneously,

- natal source (rdzas, natal substance) – coming from their own individual natal sources, referring to their individual tendencies (sa-bon, seed).

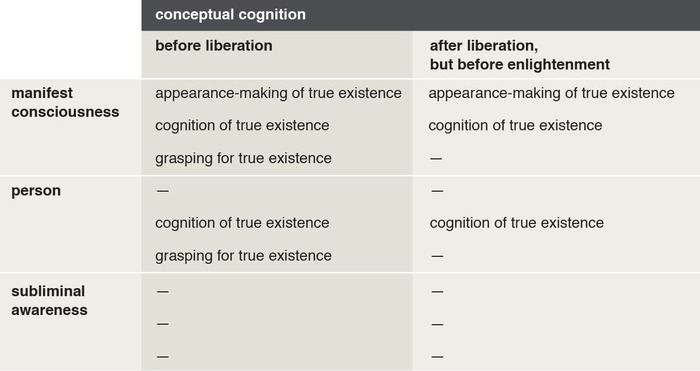

Conceptual Cognition

During conceptual cognition before liberation, the consciousness of a manifest conceptual cognition has appearance-making of true existence. The manifest consciousness and the person both have cognition of true existence and grasping for true existence. There is no subliminal appearance-making of true existence and thus no subliminal cognition of grasping for true existence.

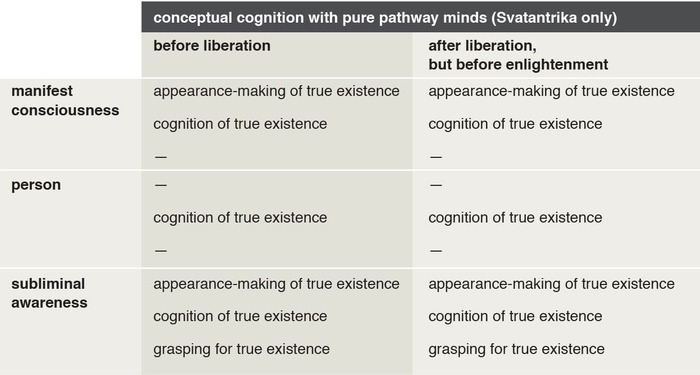

In Svatantrika, during conceptual cognition with the three pure level bodhisattva pathway minds, the consciousness of a manifest conceptual cognition has appearance-making of true existence. The manifest consciousness and the person both have cognition of true existence, but neither has grasping for true existence. But since Svatantrika includes grasping for true existence as a cognitive obscuration, totally gotten rid of only with enlightenment, it asserts that grasping for true existence still continues with the three pure level bhumi minds, but now only in a subliminal form. This is the case whether liberation is attained simultaneously with enlightenment, as Yogachara-Svatantrika asserts, or with the attainment of the eighth-level bhumi mind as Sautrantika-Svatantrika asserts according to Kunkyen. Thus, during manifest conceptual cognition with the three pure level bhumi minds, subliminal awareness has subliminal conceptual cognition with appearance-making and cognition of true existence, as well as with subliminal grasping for true existence.

In Prasangika, during conceptual cognition after liberation but before enlightenment, the consciousness of the manifest conceptual cognition has appearance-making of true existence. The manifest consciousness and the person both have cognition of true existence. Neither has grasping for true existence. In this regard, Prasangika and Svatantrika share the same assertion. However, since Prasangika includes grasping for true existence as an emotional obscuration, totally gotten rid of with liberation, there is no grasping for true existence with the three pure level bhumi minds, even in a subliminal form, and, consequently, no subliminal appearance-making of true existence or subliminal cognition of true existence.

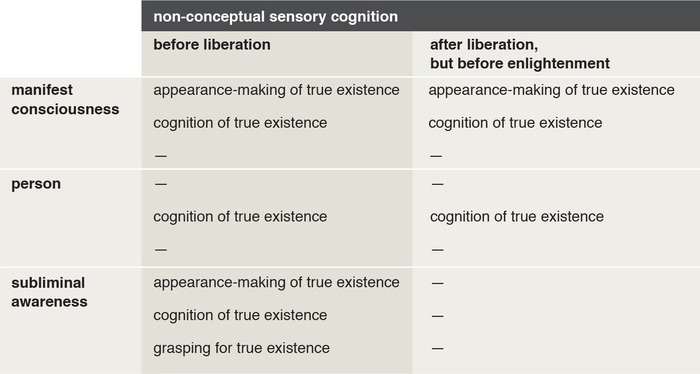

Non-Conceptual Sensory Cognition

During non-conceptual sensory cognition before liberation, the consciousness of the manifest non-conceptual sensory cognition has appearance-making of true existence, and both that manifest consciousness and the person cognize it, but without grasping for it. The manifest non-conceptual sensory cognition is accompanied by a subliminal conceptual cognition that not only makes an appearance of true existence and cognizes it, but also grasps for true existence. Thus, only the subliminal consciousness has grasping for true existence.

During non-conceptual sensory cognition after liberation but before enlightenment, the consciousness of the manifest non-conceptual sensory cognition has appearance-making of true existence, and both that manifest consciousness and the person cognize it. Not only is there no manifest grasping for true existence by either the manifest consciousness or the person, but there is also no accompanying subliminal awareness with appearance-making and cognition of true existence, let alone grasping for true existence.

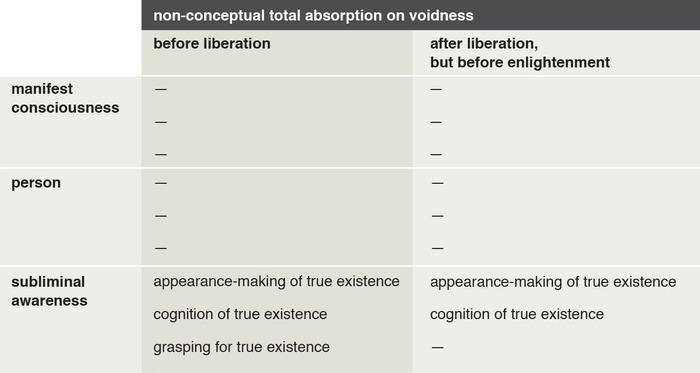

Non-Conceptual Total Absorption on Voidness

During non-conceptual total absorption on voidness before liberation, the consciousness of the manifest non-conceptual total absorption does not have appearance-making of true existence. Neither that manifest consciousness nor the person has either cognition of true existence or grasping for true existence. However, the subliminal awareness in an accompanying subliminal conceptual cognition does make an appearance of true existence and both cognizes and grasps for it.

During non-conceptual total absorption on voidness after liberation but before enlightenment, the consciousness of the manifest non-conceptual total absorption does not have appearance-making of true existence. Neither that manifest consciousness nor the person has either cognition of or grasping for true existence. The subliminal awareness in an accompanying subliminal non-conceptual cognition, however, still makes an appearance of true existence and cognizes it, but does not grasp for it.

The Jetsunpa Position in Chart Form

Conceptual Cognition before and after Liberation

Conceptual Cognition with Pure Pathway Minds (Svatantrika Only) before and after Liberation

Non-Conceptual Sensory Cognition before and after Liberation

Non-Conceptual Total Absorption on Voidness before and after Liberation