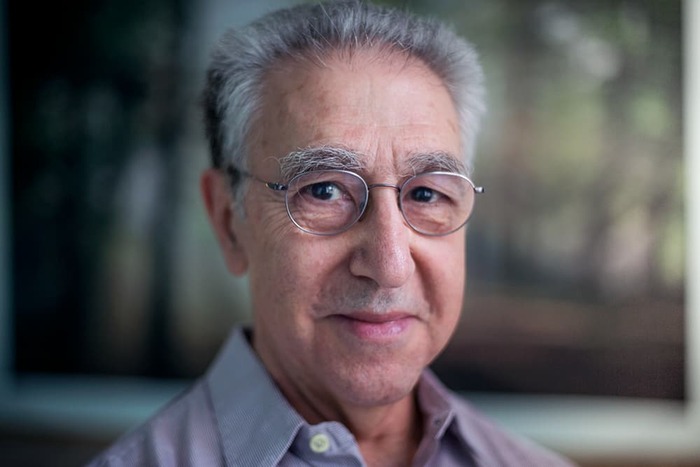

It’s Sunday morning, and I’m in a car driving through the unusually quiet streets of Berlin. Next to me sits Dr. Alexander Berzin, and we’re heading to the MindSpace office in the center of Berlin to hold an interview. We arrive and, as predicted, the office is empty. I set up all of the equipment – I’ve forgotten the tripod and so the camera is actually resting on top of piled up books – and begin probing the mind of arguably one of the modern era’s greatest Western Buddhist teachers. Any guesses? This time, we’re turning the spotlight on Dr. Berzin himself.

Dr. Alexander Berzin is a prolific Buddhist scholar, teacher, lecturer, writer, translator and, of course, he is the founder of this very website. Going to India at the height of the hippie movement in 1969 – however, not as a hippie! – to do research with the Tibetans for his Harvard PhD, Dr. Berzin moved to Dharamsala in 1972 once he received his degree. There, he studied with the most pre-eminent Tibetan Buddhist teachers of the 20th-century and became a close disciple and interpreter for Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche, one of the tutors of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Over the next 29 years in India, Dr. Berzin accumulated a vast amount of material – more than 30,000 pages of unpublished manuscripts of books, articles and transcriptions. He moved to Berlin and decided to set up the Berzin Archives website to make it all available to everyone. The website evolved in 2015 into Study Buddhism, publishing content in 32 languages and reaching the entire world.

With 60 years of Buddhist wisdom, Dr. Berzin is a fountain of knowledge and is truly able to make the Buddha’s teachings accessible in our modern age. Having taught in over 70 countries, he was a pioneer in the preparation of basic Buddhist texts in colloquial Mongolian to help with the revival of Buddhism in Mongolia and spearheaded the initiation of a Buddhist-Muslim dialogue in universities in the Islamic world.

In this interview, I speak with Dr. Berzin about how spiritual teachers and therapists differ, how to express our emotions healthily, and the role of analytical meditation in understanding our minds. Enjoy!

Study Buddhism: The last decade has seen an explosion in meditation centers and online meditation apps. In the West, meditation is often seen as a way to relax or “stop thinking,” or at best as a tool to develop mindfulness and to calm the mind. This ignores the analytical aspect of meditation, which is an important practice especially in the Tibetan Buddhist traditions. What kind of potential does meditation hold for Western practitioners?

Dr. Berzin: Yes, many people look at meditation primarily as a way to calm down, to quiet the mind and to gain a certain level of inner peace. And of course this is very important as a start, especially if our minds are all over the place with disturbing thoughts and emotions going wild, but that is only a start, really. In general, meditation means to build up a beneficial habit of mind.

Of course, we need concentration too, but as His Holiness the Dalai Lama says, the main emphasis needs to be on analytical meditation, on understanding what is going on in our minds, to familiarize ourselves so that we build up more positive attitudes and we deal with the shortcomings that we might find in ourselves.

Therefore, we need to examine ourselves in meditation, developing the habit of contemplating, “What am I doing with my life, what is my main aim, what is my main motivation? Is what I discover something that is helpful to me or is it something that’s causing me problems with how I deal with other people?”

By learning the various Buddhist methods, we then try to familiarize ourselves with them in analytical meditation. We don’t just look at the negative things that we’ve done, but we also look at the positive things and familiarize ourselves further with them.

For instance, appreciating the precious life that we have and appreciating our own kindness to ourselves, like all the effort that we put in to learn how to do things, to learn how to read, to learn how to use our minds, to learn how to relate to people, to learn how to just do mechanical things, like drive a car, work a computer, type on a keyboard and so on. In recalling all this, we come to appreciate that, actually, we’ve been very kind to ourselves. It’s not that we’re so horrible and never learned anything and don’t have any value or anything like that.

The main thing is to apply our contemplation and meditation to our lives by building up as a habit familiarizing ourselves with such realizations and reminding ourselves about them in quiet meditation. His Holiness the Dalai Lama emphasizes this as well, that the main point of meditation is actually building up these beneficial habits, which are active habits, active ways of thinking and acting, not just quieting down. Quieting down is just the start.

If we meditate in this way, then, automatically, what we’ve familiarized ourselves with is going to start to come up in our daily lives. When we start feeling sorry for ourselves and we start feeling negative, we’ll remember, “Hey, you know, actually, I’ve done pretty well!” And this gives us some encouragement.

Apart from meditation, one of Buddhism’s core concepts – that of Buddha-nature – has actually had a massive influence on the Western self-help movement. Are there any issues with treating Buddhism simply as a self-help method?

Yes, nowadays, many people are using Buddhism as a type of self-help or therapy. I think that this is problematic.

It’s true that we can derive a great deal of benefit from using the Buddhist teachings in this way, they can give us a great deal of insight into our behavior and our way of thinking. But what using Buddhism simply for self-help does is it eliminates the role of the spiritual teacher, and the spiritual teacher is very, very important on the Buddhist path. Of course, we need to have a qualified Buddhist teacher, and it is quite rare to have someone who is well-qualified. It requires a great deal of examination before accepting a spiritual teacher. A spiritual teacher is somebody who has excellent qualities, not just vast knowledge of the Buddhist teachings, but also somebody who has developed themselves, worked on themselves, who has achieved some emotional balance, who has achieved calmness, understanding and kindness.

With a qualified spiritual teacher, we need to develop, based on respect for these qualities, confidence and trust that they in fact have these qualities and appreciation and gratitude for their kindness in teaching us, guiding us, helping us.

When we develop respect for their good qualities and appreciation for their kindness, this allows us to then transfer that respect and appreciation to ourselves. If we don’t have any respect for ourselves and our own good qualities – appreciating our own kindness to ourselves in the past, that we learned how to read so that we can read books and can understand them, we learned how to communicate, we learned how to deal with people – then it is very hard to develop further good qualities, such as those of our teacher. So, working on and developing the good qualities of mind and emotion of respect, appreciation, gratitude and so on with respect to our teacher allows us to develop them with respect to ourselves. Then, we can extend this respect and appreciation from the teacher and ourselves to all others around us.

Having a very positive attitude, seeing and acknowledging good qualities of others, is also a basis for ethical behavior. It is important, then, that we respect both ourselves and others and we appreciate the kindness of both us and them. This gives us the feeling that we’re not alone – another great benefit.

Another danger of treating Buddhism just as a self-help method is that we don’t have any control to check our practice. We don’t have any feedback as to how we’re actually applying these teachings. People also tend to choose and pick from the teachings those points that they like and ignore those points that they don’t like. So, they already have an agenda beforehand of what they would like to achieve, whereas, with Buddhism, when you’re working with a teacher, you’re working with the teachings that your teacher chooses to impart. Your teacher takes you outside of your comfort zone so that you work on the difficult points that you have.

In the mind training texts, one of the pieces of advice is to work on your most serious disturbing emotion first, really tackle and deal with it. If you’re doing just self-help, you might treat yourself a little bit like a baby and not really go deeply enough into the areas where you really need the most work.

You just mentioned the importance of working with a qualified and trusted spiritual teacher, and your book, Relating to a Spiritual Teacher: Building a Healthy Relationship, reissued as Wise Teacher, Wise Student, has been very helpful for many people. In the West, we like to share a lot of personal issues with our spiritual teachers and can easily come to view them as a sort of therapist. Are these roles comparable?

Aside from the spiritual teacher serving as a role model, I think the whole interaction with a spiritual teacher is very different from that of a therapist.

When we’re working with a therapist, we’re speaking about ourselves, we’re speaking about our problems that are very personal. We share many personal facts with the therapist. With a spiritual teacher, if we look at it in the traditional way in which it has been carried out, we find that you don’t do that at all.

The teacher gives you instructions, explains the teachings, and then it’s up to you to apply them yourself in your own life. Although some Westerners like to report back to the teacher all the personal things that they’re dealing with and ask personal questions, that’s quite a Western thing. Traditionally, that’s not really what is done. The teacher might quiz you, which they very often do, and they will test you and will put you in situations in which you’re very challenged. That doesn’t happen with the therapist, so it’s a very, very different dynamic.

You were a very close disciple of Tsenshap Serkong Rinpoche for the last decade of his life. Was your relationship this traditional teacher-student one that you described? If so, did you not miss being able to share your personal issues?

I had a very close relation with my main teacher Serkong Rinpoche, but he never asked me one question about my personal life, and I never spoke with him about my personal life. It seemed totally irrelevant.

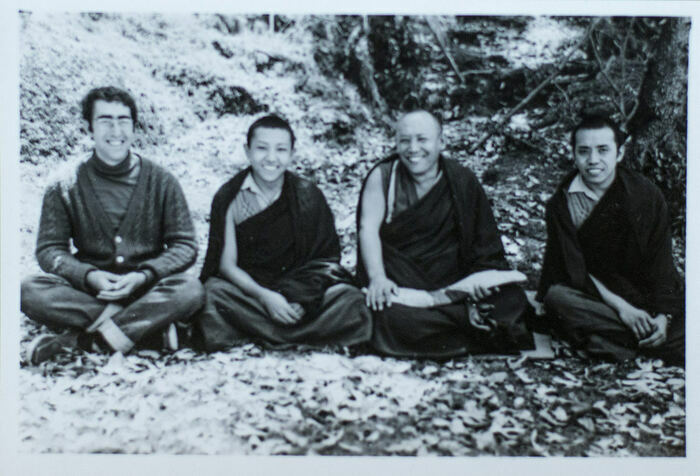

When I went to India, I went as a graduate student to do research for my PhD dissertation. At that time, in the late ‘60s, Buddhism, specifically Tibetan Buddhism, was presented as a dead area of study, like ancient Egyptian studies. In India, I saw that it was all for real. I met His Holiness the Dalai Lama; I met his teachers – at that time it was very easy to meet the greatest lamas that had received all their training in Tibet – and I realized that Buddhism is very much alive, these high Tibetan lamas knew what its teachings actually meant and that it is just too wonderful not to share with the world.

What I wanted to do was to develop myself to the point where I would be able to help make these teachings available to everyone, and that required, first of all, learning Tibetan better. I’d already had the foundation for being able to read the language from my studies at Harvard, but not the spoken language. So, I worked on that during my first years in India before I started studying with Serkong Rinpoche and became able to translate for him.

I explained to Serkong Rinpoche when I first started to study with him that “I am like a donkey! I don’t really deal with people in a very diplomatic way, in a very sociable way.” I was basically an academic nerd and said, “Please train me to be able to be of benefit to others, to be able to help transmit your teachings.” From my side, the main purpose of the relationship with him was to basically develop myself to the point where I would be able to make his teachings available to the world. This was the same attitude, or the same approach that I had with His Holiness the Dalai Lama as well.

I was very focused on this, so my relationship with Serkong Rinpoche had nothing to do really with what my personal past was and, unlike with a therapist, dealing with “Because my parents did this or my classmates did that,” therefore I feel like this. That was totally, totally irrelevant. The task was to benefit others, and this was very clear. I think this is one of the reasons why he spent such a great deal of time and effort training me.

You’ve worked a lot on making the Buddhist teachings accessible to Westerners, especially in terms of emotional hygiene, and you developed a course, Developing Balanced Sensitivity, which offers incredibly useful techniques to achieve emotional balance. How can we express our emotions healthily and deal with negative emotions such as anger when they arise?

If we feel a great deal of aggression and anger, we can do some sort of sport or something else that utilizes that aggressive energy. If that aggressive energy calms down through that process, then if there’s something that annoys us, something that somebody said that hurt us, we can think more clearly how to deal with it when our mind is calmer, more peaceful. When we are under the influence of anger and feeling really hurt, we don’t use our discrimination and we say things or do things that we often are going to regret later. So, it’s very important to calm down first.

As I said, if, in order to calm down, we need to release that aggressive energy, we should release it in healthy way, such as through sports or running and then deal with the problem. If we are annoyed with someone, we need to use our intelligence and sensitivity to the other person to know what the best thing to say would be, and of course choose the right time. You know, the right move at the wrong time doesn’t work. So, you have to choose the right time as well, when the other person is receptive, not when they’re very upset and angry with us.

In terms of expressing affection, again you have to be sensitive to what the mode of the other person is with which they can accept affection. There are some people who like to be hugged, other people who don’t like to be touched. There are many ways of showing affection, in terms of doing things for others, helping them. It’s a matter of using our discrimination. It’s not all about what will make us feel better but what will make the other person feel better.

So, we need to discriminate between what we feel like doing in the moment and what would be the better thing to do, and this can mitigate our urges to behave destructively. This leads us to your views on karma, where you describe it as a sort of compulsiveness and not as “action,” as it is so often translated. How does this compulsiveness manifest and what can we do about it?

“Karma” is usually translated in the West as “actions.” The main reason why it’s usually explained like that is because the classical Tibetan word for karma is the colloquial Tibetan word for actions. However, if karma is just actions, then what follows from that is that if you just stop doing anything then you’ll be free of all problems. That’s not at all the meaning of karma.

If you think more deeply about it, what karma as referring to is the compulsiveness of our behavior. Because of our previous behavior and conditioning, we compulsively act, speak and think in certain ways. If we don’t use discrimination to see whether what we are about to say or do is beneficial or harmful, then we get into a great deal of trouble.

This is where the problems come, whether we’re talking about compulsive destructive behavior or even compulsive constructive behavior, like being a perfectionist or wanting to correct everybody. This can also go way overboard and cause problems. So, this is really what karma is talking about: the compulsiveness of our actions, the compulsiveness of our behavior. That’s something that we need to overcome so as to avoid causing problems to ourselves and to others.

The relevance of trying to understand karma is that we often tend to act without thinking and so we need to examine our behavior. When are we compulsively acting in certain ways – whether constructive or destructive, whether as a perfectionist or somebody who is just very negative and criticizing others all the time – we need to examine and evaluate what the effects of our behavior are. What the effects are on others and what the effects are on ourselves.

We need to discriminate between when what we feel like saying or doing is going to be harmful and when it’s going to be beneficial. If you look at the teachings on karma, what they describe is that first the thought comes up to say something or to do something. This is often followed indiscriminately by the feeling or wish to say or do it. Sometimes when such a feeling comes up, we first think about it and decide to say or do it, and sometimes we speak or act without thinking beforehand. But it’s only after that wish comes up that the mental impulse, or urge, arises that compulsively draws us into acting on it. That mental impulse or urge is called “karma.” I call it a “karmic impulse” and it is compelling and brings about compulsive behavior. But, there’s a space between these two – between the thought and the wish to say or do something and between the wish and the arising of the karmic impulse that draws us into acting it out. Through meditation to train ourselves to slow things down and, with introspection to become more aware of what it going on in our minds, we become able to recognize those spaces and use those spaces as opportunities to discriminate whether or not to pursue the thought or feeling. With increasing familiarity of doing this in the controlled environment of meditation, we become able to do this in our daily lives.

If, when we evaluate what we think to say or do or what we feel like or wish to say or do and realize that it is going to be detrimental and harmful, then, as the great Indian master Shantideva says, “Just act like a block of wood.” Don’t do it. It’s not a matter of repression and suppressing. It’s not that we’re policemen with ourselves but rather that we use our intelligence. This is our greatest gift as human beings: we have the intelligence to be able to discriminate between what’s helpful and what’s harmful. We need to cultivate that, and this is what Buddhism teaches us very well how to do.

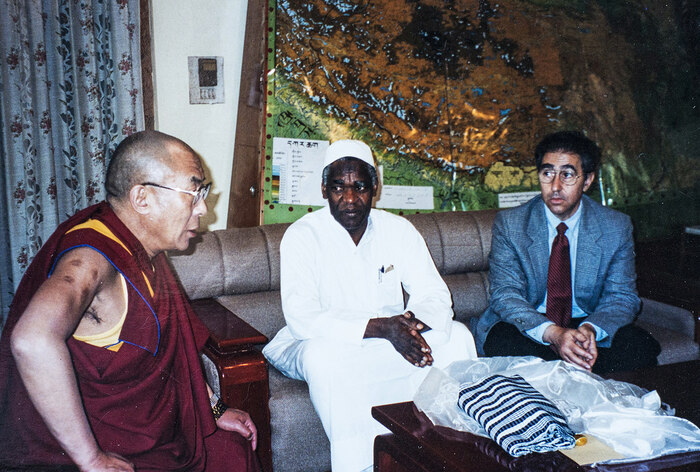

You became involved with Islamic-Buddhist dialogue after an extensive lecture tour throughout Central Asia in 1994. You came to understand how dialogue has the potential to lead to more understanding between religious practitioners as well as to increased political stability in areas where two or more diverse groups live in close proximity. What inspired you to take on this ground-breaking work?

Originally, in the ‘90s, I was looking at the situation in Central Asia and I saw that there existed there Islamic, Buddhist and Orthodox Christian civilizations. There had already been a lot of work in terms of Christian-Buddhist relations but hardly anything in terms of Buddhism and Islam. I was thinking, in terms of geopolitical considerations, that the Buddhists and Muslims need to somehow work together in order to live in harmony in this area.

That was my original consideration and, thinking in terms of how the history between Buddhism and Islam has been presented traditionally, I saw that the emphasis was very much on how the Muslim conquerors in India had destroyed the Buddhist monasteries and I thought that this was really a very one-sided way of looking at the interaction between the two civilizations..

So, I did a great deal of research, discussing with professors and religious leaders during my lecture tours in the Middle East and Central Asia, trying to understand really what the economic considerations were, what the political considerations were in that interaction. As it turns out in any sort of historical analysis, you see that the main motivation behind any sort of conquest is political and economic. This stimulated my interest further. As time passed, various terrorist acts started happening and Muslims became more and more demonized. I thought this was extremely unfortunate, so I continued my research and discussions with scholars and leaders in the Islamic world and started lecturing there about Buddhism.

For example, I lectured on introduction to Buddhism at Cairo University and 300 students came. They kept on telling me, “We’re so isolated,” in terms of lack of information, “we want to know what’s going on.” This led to the idea to make information available about Buddhism in the Islamic world and also to make information about Islam known in the Buddhist circles, because the source of conflict is usually misunderstanding and lack of information.

I reported this to His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and he was very interested in this. Once I had moved to Berlin and had started my website – called Berzin Archives at that time – His Holiness encouraged me to make the basic Buddhist teachings available there in the main Islamic languages. Not that we want to convert anybody to Buddhism – this is especially something that you don’t want to do in the Muslim community – however his point, which I understood very well, was that the cause of most misunderstanding was lack of information. As I traveled around in various Islamic countries, this was the main feeling that I had had.

I’ve been very much involved with this work since then, and I have found that it has been very positive, very rewarding. There is a great deal in common between the two belief systems in terms of the emphasis on the development of love, the development of service and help for others. The philosophical views behind this are quite different, but the effect is very much the same.

You’ve taught Buddhism all over the world, and I wonder if you’ve found that different countries like to focus on different aspects of Buddhism? What have the main differences been that you’ve witnessed in how different cultures approach Buddhist practice?

Cultural differences show up in things such as some people putting more emphasis on devotional practices while others place more emphasis on more analytical, rational types of practices. In certain places, some people like to have things set out as a course, almost like something at university, as this gives them a certain type of structure and discipline. In other places, people like to just have emotional types of experiences. It’s hard to really generalize when you go around teaching, but what I’ve always tried to do in different places is ask the people themselves what they are interested in.

You find that some people are very interested in dealing with their own individual personal problems, other people are looking to Buddhism as some sort of diversion from actually dealing with things in their life. For such persons, Buddhism becomes almost like a hobby. This is, of course, quite natural to understand, because people are very busy at work, very busy with family and they don’t have so much time for Buddhist study or practice. So, it’s sort of a timeout when they go to a teaching or when they try to do meditation.

But I think what’s very important is to try to present the Buddhist teachings in a way in which you show people how it applies to their daily lives and to put the emphasis on: “That is your practice: your practice is your daily life.” Teachings on patience, on forgiveness, on being calm, calming down need to be applied in daily life, and this is what I try always to emphasize.

Thank you, Dr. Berzin, for sharing with us your thoughts and experiences!