The Buddhist Path as the Context for the Four Noble Truths

I’ve been asked to speak about the four noble truths according to Vajrayana. The discussion of them in Vajrayana tradition can be approached in two ways, either specifically in the way in which they are presented in tantra, or we can look at Vajrayana as being a way of referring to the Tibetan tradition of Buddhism that combines the study of both sutra and tantra.

Let’s begin with the way in which sutra and tantra speak of them in common. This is the main way in which they are usually presented in the Tibetan tradition. It is based on the Indian Mahayana tradition from a particular text by Maitreya, a future Buddha. He wrote many texts, including a great commentary on the Prajnaparamita Sutras, or the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, in which there is a great deal of detail concerning the path and all the realizations that one gains along the path to liberation and enlightenment. The title of the text translates as Filigree of Realizations, indicating the multitude of potential realizations along the path.

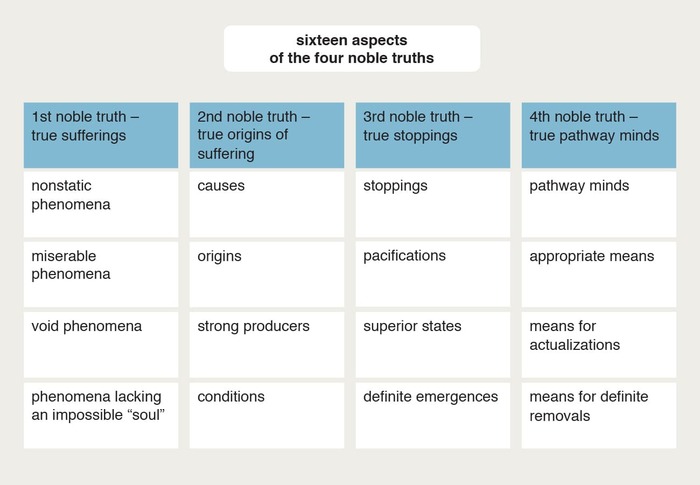

Sixteen Aspects of the Four Noble Truths

The four noble truths have 16 aspects, four to each of the truths. These comprise the main focus of meditation on the path that leads to both liberation and enlightenment. When we speak about liberation and enlightenment, liberation refers to overcoming one set of obscurations that cloud the mind, the emotional obscurations. They include the disturbing emotions and disturbing attitudes like anger, longing desire, naivety, ignorance, confusion, and so on, plus their tendencies. When we overcome all of them and their tendencies, plus the karmic impulses to act under their influence, we gain liberation.

One way that we can gain liberation is as a shravaka, a listener to the teachings, who basically follows what is called, although not a very nice name, a “Hinayana” or Modest Vehicle path. Hinayana has 18 schools and one of them is Theravada. We don’t really have a name inclusive of all 18, but we need to realize that Theravada is only one of them. We can also practice toward liberation as a pratyekabuddha, someone who practices during the dark ages between times when Buddhas are available to teach us. They work on the basis of their instincts without any teacher.

We can follow the path in one of these two ways toward liberation, or we can follow it as part of the bodhisattva path. As a bodhisattva, we would gain liberation and then go beyond to gain enlightenment. To gain enlightenment, not only do we need to overcome these emotional obscurations that prevent liberation, but we also need to overcome a deeper set of obscurations. Although these are described in many ways by the different Buddhist philosophical schools, we can call them the cognitive obscurations. These are the obscurations that prevent us from gaining omniscience.

Disturbing emotions and attitudes are based on confusion about reality, confusion about how we and everything exists. The problem is that our mind makes things appear to exist in a false and confusing way, as though everything is solid and concrete. It’s as if each thing has a big coating in plastic or a big line around it to make it individual and separate from everything else. We think that we exist like that, and we also think, “I am the center of the universe,” and that everything else is “out there” with these big lines around them. That is certainly confusing. Based on believing that, we act in all sorts of inappropriate, unfortunate ways. In order to gain enlightenment, we need to overcome this aspect of the mind that makes things appear in this confusing way, where we don’t see that everything is interrelated. This aspect refers to the constant habits for the disturbing emotions and attitudes. These constitute the cognitive obscurations.

If we can’t see that everything is interrelated, we can’t fully understand how we can really help everybody. To be able to help everybody, we need to understand every little thing that has affected each person from beginningless time. All the different factors of what each being has done in previous lives, what’s happened to them, all the historical factors that have affected them, and so on. Everything is interrelated. We also need to know, if we teach this person something, what the effect of that will be. How will that affect not only this person but everybody that this person meets from now until their liberation? Certainly, this is not very easy to understand. If our mind makes things appear in these little plastic packages, then we don’t see the relation between everything. We can’t really understand all the causes of why something is happening with somebody and all the effects of how we interact with them.

That’s what we need to overcome to become a Buddha. These are cognitive obscurations. What they obscure is Buddha-nature, the nature of the mind, which is capable of understanding everything and seeing all the interconnections. So, as a bodhisattva, we need to overcome not only all the disturbing emotions and confusion, but in addition, we also need to overcome our mind projecting these confusing, false appearances. The mind makes these false appearances, and we believe in them, acting out as if things actually exist that way.

If we are liberated, we become an arhat, a liberated being. As an arhat, our mind still makes all these confusing appearances, but we no longer believe them. We know that they are garbage, that they are not true. They don’t correspond to reality. Knowing this, of course, we don’t get upset, we don’t act out and so on. However, that’s not enough because we still don’t know how to help everybody in the best way.

The Five Pathway Minds

In order to reach liberation and enlightenment, we follow a certain development of mind that is described by the five paths. It’s the development of our understanding and our character. These are actually pathway minds, each being a level of mind that acts as a path for reaching liberation and enlightenment. All of this begins with renunciation.

Renunciation is when we have a strong determination to get free, free from all the terrible and horrible suffering we experience. We have had enough of it and want out. We want to get out not only from the suffering of this lifetime, but also from uncontrollably recurring rebirth with all the same problems over and again.

There are two aspects to renunciation. It’s not just that we want to get out, but don’t want to need to give up anything. We are willing to give up everything, including all the confusion, the disturbing emotions and so on, that are causing our sufferings with uncontrollably recurring rebirth, samsara.

Unlabored Renunciation and Unlabored Bodhichitta: The Beginning

Unlabored renunciation is when no effort is required to logically go through why we want to get out, and so on. With it, renunciation is just part of our whole aim in life, whether we are thinking about it or not. At this point, we begin these pathway minds. This is when we start. Before that, we’re just struggling to get ourselves on to the train, as it were, the vehicle of mind that will bring us to liberation. We actually get on the train when we develop this renunciation in an unlabored way.

In addition, we develop unlabored bodhichitta in the same way. Bodhichitta is when our mind is aimed at our own future enlightenment, not enlightenment in general, not the enlightenment of the Buddha, but our own individual enlightenment, which has not yet happened. We understand, however, that we can attain this enlightenment because of our Buddha-nature, and so on. We focus on that, realizing that we haven’t gotten there yet, but that it is what we are aiming for. We are aiming for that because we want to be able to help everybody as fully as possible, and the only way to accomplish that is to attain enlightenment.

Then, when we have bodhichitta in an unlabored way, when it’s just there all the time without having to think of why and all the reasons for it, we start on the Mahayana five paths. As we progress through these five paths, these five pathway minds, each of them is a level of mind, a level of understanding that will bring us closer and closer to the goal.

The Building-Up Pathway Mind

The first pathway mind is usually translated as “the path of accumulation”; however, accumulation actually means “building up.” We are gathering and building up all the tools we will need for attaining liberation and enlightenment. The tools being built up are shamatha and vipashyana. Shamatha is a state of mind that is stilled and settled, without any wandering, any flying off to things of desire, any dullness or sleepiness, or anything like that. It’s perfectly concentrated with a sense of fitness – an exhilarating sense that we can concentrate perfectly on anything for as long as we want.

Vipashyana is an exceptional perceptive state of mind. When we add vipashyana to shamatha, there is an additional sense of fitness that the mind can understand anything. When we have both these tools focused on a conceptual cognition of the 16 aspects of the four noble truths, we have completed our attainment of this first-level pathway mind.

The Applying Pathway Mind and Seeing Pathway Mind

With an applying pathway mind, usually translated as “the path of preparation,” we apply this concentration and understanding more and more, continuously, on our conceptual cognition of these 16 aspects. When we gain a non-conceptual cognition of these, we attain a seeing pathway of mind, the so-called “path of seeing,” and become an arya.

“Non-conceptual” means to cognize something not through some general idea about it or through a category, but just straightforwardly and without relying on a line of reasoning. An arya is a highly realized being who has this non-conceptual cognition. With this, we begin to rid our mind of one level of the emotional obscurations.

The Accustoming Pathway Mind and Pathway Mind Needing No Further Training

After this, we need to accustom ourselves to this non-conceptual understanding more and more. That’s with an accustoming pathway of mind or “the path of meditation.” With this, we rid our mind of more levels of obscurations until we achieve the goal, the pathway mind needing no further training as either an arhat (a liberated being) or a Buddha. An arhat has rid themselves of just the emotional obscurations, while a Buddha has rid themselves also of the cognitive obscurations.

Focus on the Four Noble Truths

Throughout all of this, we focus on the four noble truths and the lack of an impossible self experiencing them. “Noble” refers to an arya, the one who has this non-conceptual cognition. They are called the noble truths, the arya truths, because ordinary people don’t understand them. The noble truths that the aryas see non-conceptually are completely different from the way that ordinary people understand life. Aryas see that what ordinary people understand is superficial or not true and, instead, they see the true way in which things are in life.

As we work to try to really understand these four noble truths and these 16 aspects, we overcome the 16 distorted ways of understanding them, the 16 wrong views about them. From the Tibetan perspective, we study the four noble truths because they are the main topic of meditation with the pathway minds. We want to understand the 16 aspects to get rid of the 16 wrong understandings. Knowing the wrong and the correct understandings is actually very helpful, and not only when we are at these very advanced levels being discussed. Along with developing a strong motivation of renunciation or bodhichitta, it is also quite helpful to think about these truths and aspects long before we are at those levels.

When we focus on these 16 aspects, there are two parts. First, we focus on the actual details: what the aspects are and that they are true. But, in addition, we also focus on the lack of us, who are experiencing them, existing in some impossible way – such as “me” existing as some separate entity inside our head and these 16 as some other separate entities existing out there, unrelated to us. We need to understand that although our mind makes us appear to exist in all sorts of impossible ways and we believe in them, these false appearances do not correspond to how we actually exist.

In short none of these 16 aspects exist in some impossible way: coated in plastic, by itself, isolated from everything else. There isn’t some “fact” up there that we need to learn in order to pass a test or something like that. And there isn’t a “me,” totally unrelated to these 16, that has to learn about them even though we experience them without knowing. That’s actually what meditation on the spiritual path to liberation and enlightenment is all about, along with a basis of renunciation and bodhichitta, which are based on love and compassion and so on.

The Four Aspects of True Suffering

True Suffering Refers to the Five Tainted Aggregates as Exemplified by Our Body

What are these 16 aspects? To understand them, it is necessary to also understand the four noble truths with a bit more detail. True sufferings, the first of these aspects, refer to the five tainted aggregates, as exemplified by our body as the basis on which we experience them. “Tainted aggregates” is jargon, of course, and we need to also understand what that means.

The aggregates refer to everything that makes up our experience. Every moment of our experience is made up of one or more things that are classified in five groups, in other words, five aggregates. This classification scheme is just a mental construct to help us analyze and understand our experience. In every moment, one or more items from each of these groups are going to be present as part of what we are experiencing.

What do we experience in each moment? Let’s describe this in an order that makes it easier to understand. We have some form of consciousness, whether it is seeing consciousness, or hearing, smelling, tasting, feeling a physical sensation, or mental consciousness, for instance with thinking or dreaming. In every moment, we are on one of these channels, like a channel on the television.

Then, in every moment, there is some form of physical phenomenon that is perceived or known by one of these types of consciousness; it could be a sight, a sound, a smell, a taste, a physical sensation, or we could be thinking about anything. In addition, there is some cognitive sensor, like the photosensitive cells of the eyes that seeing depends on. Of course, our body is there too as the physical location where these cognitions take place, but in the scheme of the five aggregates the body is included only as the sensor of physical sensations.

Next, there is a feeling of a level of happiness. The term “feeling” refers only to that and not to emotions. How do we feel? Is it a feeling of happiness or unhappiness? When we see somebody, do we feel happy seeing them or unhappy? What about when we think of them? Happiness means that we want it to continue, unhappiness means that we want it to stop. Some level of feeling is there every single moment. It doesn’t need to be dramatic; nevertheless, some level is there every moment. Actually, feeling is defined as how we experience the ripening of our karma. For instance, one person eats cheese and feels very happy; the next person eats the same cheese and hates it and feels unhappy. That’s the result of our karma.

In every moment, we also have distinguishing. We need to able to distinguish, for example, the colored shapes of someone’s face from the colored shapes of the wall. If we can’t distinguish that, we can’t actually see the person, can we? What are we looking at? We are looking at dots of colored pixels, aren’t we? We’re seeing colored shapes. We need to be able to put them together to distinguish one thing from another thing. That is also there all the time. That’s sometimes called “recognition,” but that is not a good translation.

Lastly, the fifth one is everything else, such as all our emotions, concentration, sleepiness and so on.

These are the five aggregates. Every moment, we have one or more items from each of these five, and the complex of them is what makes up our experience. What we are experiencing in each moment changes all the time, and each component in each of these five is changing at a different rate. We are seeing, hearing and thinking different things, and our level of happiness and unhappiness goes up and down. We are distinguishing a nose from the rest of the face, for example. Basically, we are distinguishing all sorts of things. Of course, in addition, our emotions, our concentration and our interest change all the time. All these things are changing continually.

We call these aggregates “tainted,” sometimes translated as “contaminated,” which is not a very nice word. What does “tainted” mean? To understand that, we need to look at how these tainted aggregates arise. They arise because of our disturbing emotions, and in that way, they are tainted by them, sort of polluted by the disturbing emotions. Whether it’s attachment, anger, naivety, pride, or jealousy, the five aggregates are tainted by them. The effect of being tainted is that the tainted aggregates perpetuate themselves; they create further moments of themselves. That is true suffering.

What are the four aspects of true suffering?

The First Aspect of True Suffering

The first of the four aspects of true suffering is that the aggregates, as exemplified by the body, are non-static phenomena. Non-static means that they do not stand still; they are changing moment to moment. This body and the continuum of aggregates experienced based on this body are going to come to an end when we die. But then we will have another body and more aggregates in our next lifetime.

In addition to the suffering that this body and lifetime are impermanent and will come to end is the fact that each moment they are getting closer and closer to their end. Of course, there will be continuity; there will be another lifetime and another body, but we are not talking about that. What we’re talking about is within one lifetime, the body and this life will come to an end, and every moment they change and get closer to that end.

The Second Aspect of True Suffering

The second aspect of true suffering is suffering, and although only the word “suffering” is used here, perhaps we need another word, “miserable.” The second aspect is that the aggregates, as exemplified by the body, are miserable. Why are they miserable? They are miserable because, on the basis of our body, we experience all the aggregate moments of the sufferings of birth, sickness, old age and death. We have things happen to us that we don’t want to happen, we often don’t get what we want, and so on.

In addition, as explained in Buddhism, there are three types of suffering in general. One type of suffering is the suffering of unhappiness. It could be unhappiness based on pain or unhappiness based on what we don’t like, or it could be unhappiness for many, many different reasons. We shouldn’t think of this just in terms of physical pain, but mental as well. Pain is just a physical sensation. We are talking about the feeling where we are unhappy about something or some experience, we want to be parted from it and, not being parted, we suffer.

The next type of suffering is the suffering of change, and that refers to our ordinary happiness. Our ordinary happiness is a big problem. Why is it a problem? It’s because it doesn’t last, and we never know when it’s going to end or what is going to come next. It is never enough. It’s frustrating and never satisfies. Our ordinary happiness, although we may enjoy it for a little while, offers no security. Even when our body is strong and healthy, we never know when we will catch a cold, do we? That is the second kind of suffering.

The third kind of suffering, called “all-pervasive suffering,” is what we are especially talking about in Buddhism. All-pervasive suffering refers to the fact that we have this tainted body and experience on its basis these tainted aggregates. Constantly affected by anger, desire, attachment and so on, having a body and experiencing such aggregates perpetuate themselves. This is the basis for continuing to be repeatedly unhappy or to experience this ordinary type of happiness, the suffering of change. That is the real problem. The real problem is repeatedly having such a tainted basis, like our body.

It is said sometimes if we didn’t have a head, we wouldn’t have a headache. The problem is not the headache; the problem is always having the type of head that is going to get a headache. The physical constitution of our body is very delicate and easily gets thrown out of balance. Our emotional stability easily gets upset. That is what we need to get rid of, this “miserable” aspect. In short, these tainted aggregates as exemplified by our body are “miserable” because they are the basis for the other types of suffering.

The Third Aspect of True Suffering

The third aspect of true suffering is that the aggregates, such as our body, are void phenomena. “Void” means that they are missing something. There’s something absent. This is sometimes called “empty.” What is our body missing? What doesn’t it have? It lacks what we would call an impossible “soul.” In Buddhism, it’s mostly translated as a “self.” Nevertheless, if we really look at it, it is talking about the Hindu concept of atman. A “soul” is perhaps the closest that we would say in our Western thinking.

Buddhism asserts that the type of soul believed to exist in these other Indian philosophies is illogical and therefore impossible. We tend to identify with the soul, however, and say that it’s our “self,” “me,” but that is not who we are. What is missing, what the body and aggregates are devoid of, is a soul as defined in the non-Buddhist India philosophies. We exist – Buddhism does not refute that – but we don’t exist as the type of soul as defined by these Indian schools of thought. Buddha was specifically talking about what everybody believed on the Indian subcontinent at his time.

What are the characteristics of a soul that the Buddha was refuting? At Buddha’s time, the belief was that there is a soul that is eternal and unchanging. Buddhism calls this the “coarse impossible soul” or “coarse impossible ‘me.’” Now, Buddhism also says that the individual self, “me,” continues forever with no beginning and no end. The fact that the self goes on forever is not the problem. Nonetheless, to think that the eternal self, “me,” doesn’t ever change and is not affected by anything is what’s impossible.

We might think, for instance, that we are always here. We went to sleep last night and got up this morning, and here we are again, always the same “me.” We haven’t changed. It is still “me.” We might think that someone can hurt our body, but they can’t hurt “me.” These are examples of the belief in a soul or “me” as something that doesn’t change and is unaffected by anything.

The second characteristic of this impossible “soul” or “me” is that it is a monolithic, partless thing. In some Indian philosophies, the belief is that each of us is one with the universe, a partless whole of all of life. We are all "one,” or we are just the whole universe. These are Hindu beliefs and absolutely not Buddhism. Another possibility is that the soul is a tiny partless spark of life that goes from one lifetime to another. It always stays the same. That is also impossible from the Buddhist point of view. There are many parts or aspects of us as a person. There is a physical side to us, an intellectual side, an emotional side, a professional side, and so on.

The third feature of this type of “soul” or “me” is that it is completely separate from the aggregates. In other words, it comes into a body and mind at conception, and like living in a house, it inhabits or lives inside them as a separate entity, unrelated to them, and merely uses them to experience the five aggregates that make up each moment. The self controls them, like somebody sitting at a computer and pressing all the buttons. It is sitting in our head and speaking.

Actually, it feels like that, although that is completely false. We imagine that the one that’s talking inside our head, that’s “me,” this little spark of life that never changes. Whenever we do something, it’s still “me,” looking at this and doing that. We think, “I did that,” and so on. We imagine that this “me” is completely separate, that it controls and uses the body to do things and the brain to think things, and then leaves them and goes to another house, into another body and another brain, and uses them. That’s impossible. The self is totally dependent on having a physical basis and cannot exist without one. So, the third aspect of true suffering is that the body, as the basis on which to experience the five aggregates, is devoid of all three of the characteristics of that kind of impossible “me.”

What is the suffering associated with our body being devoid of this coarse impossible “me?” The suffering is that the “me,” the self, being something that cannot exist independently of a body, is dependent on this body during this lifetime and must take care of it. We can’t ignore it because we think that we’re clean, it’s just our body that’s dirty. We need to clean it and feed it, give it enough sleep and so on. We need to do this despite this body being filled with unclean substances – undigested food, feces, urine, blood, mucous and so on. As the great Indian Buddhist master, Shantideva, said, we are like slaves to our body, having to take care of it all the time.

The Fourth Aspect of True Suffering

The fourth aspect of true suffering is that the body as the basis for experiencing the five aggregates also lacks an impossible “soul.” This is referring to a more subtle level of an impossible “me'.” It’s an impossible “soul” or “me” that can be known all by itself. We all believe in this because automatically it feels like that. For instance, when we think of our very close friend, what do we think? We think that we know our friend, since we can see our friend every day.

What does that mean? We actually see a body. How can we possibly know this friend, or see this person, without seeing their body? How could we know our friend without knowing something about them? It could be their name, or what they look like, or the sound of their voice on the telephone. It’s only on the basis of hearing the sound of a voice on the phone that we can say we’re hearing our friend. It’s only on the basis of seeing their body that we can say that we’re seeing our friend. What is impossible is a “me,” a person, our friend, that we can know all by itself without also knowing any of the aggregates. We can’t just see our friend and not see their body or a photo of their body.

We always think in that false way, however, as in, “You did that to ‘me’; you said that to ‘me.’” It’s as if we can know “you” independent of a body, independent of the sound of the words you said, independent of anything. “You are a terrible person!” What is that? There is no “you” that we can know or think about, accuse of anything, or get angry about separate from the person’s body, speech, or whatever.

It is the same thing with “me.” It is impossible to see or hear or think about our “self,” “me,” without simultaneously seeing some part of our body, hearing the sound of our voice, or thinking about something in our aggregates. We see ourselves in the mirror or our weight on a scale and think, that’s not “me.” “I don’t look that old, I’m not that fat.” The suffering here is that there is no “me” that can be known separately from what our body looks like or weighs, and so we need to deal with our body being old and fat. So, these aggregate factors, such as the body, lack both a coarse and a subtle impossible “soul” or “me.”

Clearly, these types of aggregates, and especially our body, are true suffering. We need to really understand these four aspects, that our body changes all the time, that it is miserable, getting sick and so on, and that it lacks these two types of impossible “me.” If we understand that, then we have identified and understood the real problem, true suffering.

The Four Aspects of the True Origins of Suffering

Next, let’s examine the true origins or the true causes of suffering. This is interesting and very deep. If we speak in general, the true causes of suffering are the disturbing emotions and karma. But here, the true origins of suffering refer to something very specific. It has to do with the mechanism of rebirth through which the tainted body, as true suffering, perpetuates itself.

Overview of the Effects of Karma and the Twelve Links

In Buddhism, how does rebirth work? As presented a bit earlier, true suffering is exemplified by the body that we get over and again with uncontrollably recurring rebirth, samsara, with all the suffering that is involved with having this type of body. The body is the basis for experiencing the aggregates and all the sufferings they contain. Therefore, the real cause that we are investigating is the cause, or the origin, for continuing rebirth with this suffering type of body in whatever life form that entails. It might be as an animal, a ghost, or whatever. So, to identify the true origins of suffering, we need to understand the mechanism of rebirth as described in terms of what are called the “twelve links of dependent arising.” This is another very basic topic in the Buddhist teachings, but there is no need to go through all twelve at this time.

What actually happens in life? We are always thinking that we exist as some impossible “me.” We think, “Here I am, all by myself. I know ‘myself.’” Or we think “I’m going to find “myself.” I am going to express “myself.”’ We believe that this “me” could be known separately from a body or mind or whatever.

Believing that we exist in this impossible way, then based on that confused misbelief we experience disturbing emotions. With anger, we don’t like something, and so we compulsively act in destructive ways. We’re going to hurt it or kill it to get it away from “me.” Or if we have longing desire for something, we’re going to steal it just because we want to get it for “me.” With naivety, we might think that we can act in any way that we like and there will be no effect from our actions on “me.” Based on our misconception of “me,” we even act compulsively in constructive ways, such as being kind to someone so that they will like “me” or think that I am wonderful and love “me.” It is actually very selfish to be nice to somebody or help them when our reasons for being nice are essentially all ego based.

When we act in these compulsive ways, our karmic actions leave certain impressions on our mental continuum. The impressions refer to karmic tendencies to repeat these actions and karmic potentials for experiencing happiness and unhappiness and to get the type of body in a next life that is going to be the basis for experiencing more of these tainted feelings.

However, something has to activate that karmic aftermath, specifically the karmic potentials, at the time of death so that we are thrown into another rebirth. What activates them? This is what the twelve links are talking about, and this where the true origins of suffering come in. “Craving” is the first thing that activates the karmic potentials, and this craving is in response to the tainted feelings we are experiencing specifically at the time of death. If we are experiencing happiness, there is craving directed at it, a strong desire not to be parted from that happiness. The happiness could be from being with our loved ones or from having all our possessions around us, and we don’t want to lose them. When we have that type of strong craving when we are about to die, we don’t want to let go of the happiness we are experiencing on the basis of this body.

We also might have craving to be parted from suffering, from pain. For instance, if we are dying from cancer with a lot of pain, we want to be free from that. If, on the other hand, we are deeply absorbed in an advanced state of concentration, we experience just a neutral feeling and we crave for it not to decline. In addition to these three possible types of feelings we might be experiencing at the time of death, there’s also craving to just continue existing. We don’t want to stop existing with this body.

There is also a second attitude that activates our karmic potential and that follows from craving directed at our tainted feelings. It is called an “obtainer attitude,” an attitude that obtains for us a further rebirth. There are several of these attitudes, but the main one is thinking in terms of ourselves as existing as some sort of impossible “me” experiencing these feelings and, based on that, grasping for that impossible “me” to correspond to reality. Together with craving directed toward these feelings, this obtainer attitude activates the karmic potentials in such a way that a karmic impulse arises that throws our mental continuum into the next rebirth with another body that is going to get sick, grow old, and have all the problems that everyone faces in life.

The true origins of suffering are exemplified, then, by our tainted feelings of happiness and unhappiness, as well as this neutral feeling, which are the objects of our craving and of our misbelief that they are being experienced by an impossible “me.”

We want to rid ourselves of ever having a tainted body – true suffering – and to accomplish that, we need to get rid of these tainted feelings – the true origins of true suffering. If we rid ourselves of tainted feelings, there will be nothing that we will crave after when we die or grasp for an impossible “me” experiencing them when we die, and so there will be nothing to activate our karmic potentials at the time of our death. If nothing activates our karmic potentials at the time of our death, we will not experience a samsaric rebirth with a tainted body thrown by a so-called “throwing karmic impulse” that has arisen from our activated karmic potentials. Instead, our mental continuum and self will continue with an untainted body of an arhat or a Buddha.

What are the four aspects of tainted feelings as true origins of suffering?

The Four Aspects of True Origins of Suffering

The first aspect of true origins of suffering is that our tainted feelings are the cause of our true suffering, meaning that they are the objects of the craving that activates our karmic aftermath, which brings about the true suffering of a tainted body in further rebirths.

The second aspect is that our tainted feelings are the origin of our true sufferings. They are the origin, in the sense that a tainted body is going to arise again and again in further uncontrollably recurring rebirths. It is like a field in which the crops grow season after season.

The third aspect is that our tainted feelings are the strong producer of our true sufferings. This means that praying to a creator god is not stronger than our craving after them at the time of our death, and so praying to a creator god cannot prevent our rebirth with the true suffering of having a tainted body.

The fourth aspect is that our tainted feelings are a condition for the arising of our true sufferings. The arising of tainted feelings at the time of our death are the condition for craving after them to arise, which are what activates our karmic potentials, which gives rise to the throwing karma for taking rebirth with another tainted body. Our tainted feelings are like water and fertilizer as conditions needed for a plant to grow.

Those are the four aspects of the true origins of suffering.

The Four Aspects of the True Cessations of Suffering

The third noble truth is true stoppings or true cessation. What does that mean? A stopping is the absence of something from a basis that it was never an integral part of – for instance, like the absence of dust on a mirror. Dust was never something that was part of the nature of a mirror. In the case of the third noble truth, the true stopping is the absence of some or all of the emotional and cognitive obscurations from the conventional nature of the mind. This occurs only in the case of the mental continuum of an arya. An arya is somebody who has non-conceptual cognition of these 16 aspects of the four noble truths.

The mind, here, refers to mental activity and its conventional nature refers to the activity of giving rise to a cognitive appearance, like a mental hologram, of some object of cognition and a cognitive engagement with that appearance. Giving rise to an appearance and cognitively engaging with it are two different ways of describing one moment of mental activity, and this activity occurs without a separate “me” that is making it happen or observing it happen and without some separate mind, like an apparatus that a separate “me” is using to make it happen.

The two obscurations are not part of the conventional nature of the mind. Although they taint or cloud the mental activity of everyone of lesser attainment than an arya, they are removable, and we can achieve a true stopping of them such that they never return. This is achieved by the power of applying an effective opponent, a true pathway mind. They will not go away just by themselves.

When we become an arya, we achieve a true stopping of a portion of the emotional obscurations. As we proceed to attain higher and higher stages of an accustoming pathway of mind, the path of meditation, we rid ourselves of a larger and larger portion of the emotional obscurations. When we have attained a true stopping of all of them, we become an arhat, and when, on top of that, we achieve a true stopping, step by step, of the cognitive obscurations, we become a Buddha. Those are the true stoppings, and throughout the stages of attaining them, the conventional nature of the mind remains the same. These true stoppings are forever, and they are not going to change or be affected by anything else. This is because the conventional nature of the mind was always free of them. We can see how this is related to the discussion of Buddha-nature, the pure nature of the mind.

What are the four aspects of true stoppings?

The first aspect is that that the conventional nature of the mind naturally has a stopping. The mind’s conventional nature never was tainted or obscured by the fleeting stains of the two obscurations.

The second aspect is that the conventional nature of the mind has a pacification. Pacification means that the obscurations have been quieted down and removed such that they will never arise again. The conventional nature of the mind is an everlasting state of peace.

The third aspect is that the condition of the conventional nature of the mind is a superior state. It is superior to just a temporary removal of some portion of suffering, like the removal of the suffering of unhappiness when we attain rebirth as a god on the plane of ethereal beings, the so-called “form realm.” Unlike the mind in such a rebirth, it has the natural bliss of being free forever of suffering.

The fourth aspect is that the conventional nature of the mind has a definite emergence. It is definitely out of the state of experiencing true suffering and its true origins. The definite emergence is forever.

The Four Aspects of True Pathway Minds

Lastly, the fourth noble truth is true pathway minds, which refers to the discriminating awareness accompanying the levels of mind of an arya focused non-conceptually on voidness. This noble truth is not talking about a path or road like one outside that we walk on. It is talking about a mind that acts as a pathway for attaining true stoppings to reach the goals of liberation and enlightenment.

From the attainment of a seeing pathway mind all the way to attaining a pathway mind needing no further training, the same discriminating awareness of voidness accompanies the non-conceptual cognition of voidness. But with increasing levels of positive force from unlabored renunciation and unlabored bodhichitta and increasing amounts of deep awareness from more and more moments of non-conceptual cognition of voidness, the discriminating awareness gets rid of more and more levels of the obscurations.

What are the four aspects of a true pathway mind? The first aspect is that discriminating awareness of the four noble truths and the voidness or lack of an impossible “me” experiencing them is a pathway mind in the sense that it serves as a way to leave behind being an ordinary being, to become an arya and onwards to become an arhat and eventually a Buddha.

The second aspect is that discriminating awareness is an appropriate means. It’s an appropriate, proper and fitting way to be able to rid us of the emotional and cognitive obscurations. There’s a long discussion of how and why it works, which is important to understand, but we won’t delve into that at this time.

The third aspect is that discriminating awareness is a means for actualization. It is a way to actually make these various attainments of an arya happen. It’s a way to actually attain liberation and enlightenment.

The fourth aspect is that it is a means for definite removals. It is a method for definitely removing forever the two obscurations and so definitely removing forever true sufferings and their true origins.

Summary of the 16 Aspects

These are the 16 aspects of the four noble truths that we focus on in our meditations with a building-up pathway mind up to a pathway mind needing no further training. In meditation we focus on both the details of the 16 and on the voidness of an impossible “me” experiencing them. We do that with renunciation, the strong aim to get out of this suffering and its origins, and a willingness to give up everything. We are doing this as a Mahayana practitioner with bodhichitta. We’re aiming for our own enlightenment with the pathway minds that bring about all these true stoppings. We’re aiming for all the understanding of a Buddha that brings that about, in order to be able to help everybody, as much as is possible, to also overcome true sufferings and their true origin. On the basis of that renunciation and that bodhichitta motivation, along with discipline, perfect concentration and many other tools, we work with these 16 aspects over and over again, going deeper and deeper until we can be non-conceptually aware of them all the time.

We need to understand the details of the true sufferings we face, as exemplified by our tainted body attained over and again with each uncontrollably recurring rebirth, and its true origins, as exemplified by our tainted feelings that we crave after and grasp for an impossible “me” experiencing them at the time of our deaths, which trigger these rebirths.

Basically, this means we want to get rid of the misunderstanding about how “me” and everything exists. We want to get rid of that because, based on that misunderstanding, we have craving and grasping for an impossible “me.” We focus on the truth that there is no such thing as this impossible “me,” a true solid “me” that is suffering, that is afflicted by this origin of suffering, that will attain these true stoppings, and that will do this through gaining these true pathway minds. There’s no true solid “me” that’s involve with any of these.

In understanding all of this, we work to get rid of all the distorted, incorrect ways of our current understanding. Now that’s very interesting to investigate and discuss. What do we think? What is our normal, distorted way of looking at life?

The Four Distorted Ways of Embracing True Sufferings

The first distortion is that we think what is unclean is clean. In other words, the way we view our body as being clean is distorted. If we think about it, when we peel off the skin in our minds, we see that the body is filled with all sorts of unpleasant things. If we look at what is inside our stomach and our intestines, what we would see is not very nice. However, we only think on a very superficial level that the body is beautiful. This way of thinking that our body is clean and wonderful is incorrect. It’s not clean, and it’s not wonderful.

Shantideva, the great Indian master, put it very nicely. He said that if we took some food, even the most delicious food, and we put it into a mouth – our own or someone else’s mouth – and chew it a few times and then spit it out, nobody would consider that clean anymore. Therefore, how can we consider the body that made it that way as something clean? If we think what happens after it’s gone through our digestive system and comes out the other side, then again, what is this body except a very wonderful factory for making waste? That is what it does. We throw things into it, and it changes them into waste that comes out the other end. Clearly, it is not clean.

Don’t beautify the body and think that it is so wonderful. Tibetans use very colorful expressions. How shall we say it nicely? They say that no matter how much we clean a turd, a piece of shit, it’s not going to become clean. Shit is shit; we can’t clean it and make it not what it is. That’s our wrong view about the body.

The second distortion is holding what is suffering to be happiness. We think that our body is a source of happiness. We believe that if we take good care of it, exercise, follow a strict vegetarian diet, have a good sexual life, dress it with the latest fashions, wear the proper make-up, and so on, we will be happy. But whatever worldly happiness we gain in these ways never last. They are just examples of the suffering of change.

If we examine this issue, we don’t want to eat just once in our life; we don’t want to have sex just once and then that’s enough; we want more and more. It is an interesting question. Think of our most delicious favorite food. How much of it do we need to eat in order to enjoy it? We don’t think that just a single taste of it is enough, do we? We want more, a second helping for sure. Of course, then it makes us sick if we eat too much. Even if we have eaten it, then we want to eat it again. Any happiness we gain with our body turns to the suffering of frustration because it always ends and never satisfies.

The third distorted view is holding what is non-static to be static. We think that our body is going to be eternally young and healthy. We want it always to stay the same, but actually our body is very fragile. It is affected by causes and conditions and so the slightest misstep can cause us injury and pain. No matter what we do, our body will develop sicknesses and grow weaker as we get old. Our senses will fade. Because the body doesn’t last forever, but slowly deteriorates and inevitably expires, like a bottle of milk that we don’t know its date of expiration, it is incorrect to consider it to be static.

The fourth distortion is holding what is not established as an impossible “soul” to be an impossible “soul.” We identify this body as “me.” We think of our youthful thin body, and still think that’s “me.” Then, as we look in the mirror when we are older and a little bit fatter with grey hair, we think, “That’s not me. I don’t really look like that. That can’t be me.” We still feel like the young and attractive “me.” We all think like that. That’s this wrong view. The correct understandings of the four aspects of the noble truth of true suffering rids us of these wrong views.

The Four Distorted Ways of Embracing True Origins

The distorted way of thinking about true origins is very interesting. The first has two parts: holding that suffering has no cause at all or that it comes from a discordant cause. We think that our problems are just the way it is in life and there’s no cause. Furthermore, we can think in terms of “bad luck” or that suffering comes from some other discordant cause. In other words, from a cause that doesn’t fit it. This is, for instance, thinking that all our suffering comes from materialistic problems. We think that if we had a beautiful house and money, then we would be happy. All our unhappiness comes from material reasons. That’s a wrong view.

The second distorted view is thinking that suffering comes from a single cause. We do this all the time. Suffering and problems come from a combination of many, many causes and conditions, but we think of only one. We might think that we didn’t do enough to help our child when our child does poorly at school; it’s our fault. The only reason why things happen in the world is because of us. We see ourselves as the single cause. We weren’t good enough. We made a mistake, and that is why everything failed. We think like that, don’t we? That is where guilt comes in. However, that’s false. Things happen because of a million different causes and conditions that all come together, not one single cause.

The third distortion is that suffering is created and sent ahead by the mind of some other being, such as Ishvara, the creator god in some of the Hindu philosophies. This is believing that suffering comes from a creator, a god up in the sky who feels like sending us suffering sometimes, and sometimes doesn’t feel like it. It’s because we are a good boy or good girl; or, if we didn’t obey them, we’re a bad boy or bad girl. It could also be just because God felt like it for no reason at all. This is a false view.

The fourth distorted view refers to something specifically in the Jain philosophy, another school of philosophy in India. Regarding the cause of suffering, there is something permanent by nature, but it changes temporarily according to the occasion. This is to think that we have a permanent soul that is blissful and stays there all the time. We think that it is because of our association with worldly matters and material things that we have suffering and problems. If we could just remove ourselves, detach ourselves completely, and basically don’t do anything, we could gain liberation. They think that we need to starve ourselves to death because if we eat, we may swallow some small living animal. We think that we need to sit unmoving because if we walk, we are going to step on something. If we don’t do anything, that’s liberation. If we could remove ourselves from all these material things, then the temporary suffering that happens wouldn’t happen anymore. We come to the basic nature of the soul, which is blissful. This is a false view.

Buddha rejected that view as being fanatic and extremist. We have the types of bodies where no matter what we do, if we walk on the ground, we are going to kill something. That is the problem of having these types of bodies. If we eat, drink, or breathe, we are going to kill some living organism. The way out of that is not to sit and do nothing. It is to stop the mechanism that throws us into continuing to be reborn with that kind of body. Instead, we want to attain as an arhat a “light body,” whatever that refers to. However, that’s another topic.

The Four Distorted Ways of Embracing True Stoppings

The first wrong view regarding true stoppings is that there’s no such thing as liberation. A lot of people think that. There’s no way out, so we need to just shut up and accept that there’s suffering. Make the best of it and live with it. That’s an interesting view. Do we think like that? We try to minimize our suffering, but basically, we believe we need to learn to live with it. That’s not the Buddhist view. It’s considered a wrong view. There definitely is liberation. There’s definitely a true stopping. We can stop suffering and its causes forever.

The second distorted view is holding that certain specific tainted phenomena are liberation. That is referring to the deepest states of absorbed concentration attained in meditation, what we call in Sanskrit the dhyanas. Once a practitioner has achieved perfect concentration, then they can go deeper and deeper into subtler and subtler levels of absorption in which certain mental factors, like certain feelings, are temporarily stopped. It is not necessarily a Buddhist practice; Hindus do this as well. In these states, we temporarily don’t have any physical or mental suffering or unhappiness. We might just experience mental happiness or just a neutral state of mind. In each of these different levels, we temporarily achieve a stopping of these other levels. Our state becomes finer and finer. We just sit there and don’t do anything else in these absorbed states. It is the false view to think that those states are liberation. They are not. When we come out of meditation, there again are all the same types of problems and suffering.

The third distortion is holding some specific suffering states to be liberation. This refers to one of the higher states of the divine beings, the gods. The god realms are divided into three planes, and the highest of them is the plane of formless beings, the so-called “formless realm.” The gods on this plane of existence lack gross bodies. Their bodies are made of very subtle energy. The distorted view is to think that if we attain such a rebirth, we have reached true liberation. However, this is not the case, because even that kind of rebirth comes to an end.

The fourth wrong view is holding that although there may be a depletion of suffering, it’s something that will recur. In other words, thinking that we can get rid of suffering, but only for a short time because it’s going to come back again. Thinking that there is no such thing as being rid of suffering forever. This isn’t true. These are the four wrong views regarding true stoppings.

It becomes very interesting to think about and really understand what we mean by liberation. It’s very important in the Buddhist studies, if we’re going to aim for liberation and enlightenment, to be convinced that is actually possible. If we don’t think it is possible and if we don’t think that we can do it, we are never going to aim for it. If we think that even though some of those Buddhas in some ancient time in Asia could do it, but we can’t do it, this needs to be examined. It is very important to be convinced that true stoppings actually can happen and that we can attain them and that these wrong views are false.

The Four Distorted Ways of Embracing True Pathway Minds

With respect to the true pathway minds, the first wrong view is holding that there is no such thing as a pathway mind that leads to liberation. In other words, there is no way out. It doesn’t matter what we understand, we think there is nothing that can rid us of uncontrollable recurring rebirth and suffering.

The second distortion or wrong view is to hold that a pathway mind of meditation on the lack of an impossible “soul” is an inappropriate means. In other words, we think that if we meditate on there being no such thing as this static, unchanging “soul” that is the spark of life, or the size of the universe, or any of those incorrect characteristics, that it isn’t going to help. We don’t think that refuting such a “soul” or self is going to lead to liberation, and that it’s the appropriate method.

The third wrong view is to hold that certain specific states of mental stability, the dhyanas, by themselves are pathway minds leading to liberation. We think that if we can attain just these deep meditative absorptions, that is enough, and that getting these by itself will lead to liberation. That’s not true, as these states of mind are only tools that help us; they are not the actual method.

The fourth incorrect viewpoint is that there is no such thing as a pathway mind that can bring about the non-recurrence of suffering. In other words, there is nothing that we can do that could get rid of true sufferings and their true origins forever.

These are the 16 wrong views. This type of study and meditation on them are the foundation for the Buddhist path according to this textual presentation. This is mainly the case in other forms of Buddhism as well. Basically, the four noble truths are what Buddha taught. In Maitreya’s text that we have been examining, it goes into it in much more detail.

Application of the 16 Aspects of the Four Noble Truths in Tantra

Let’s complete this discussion by viewing the 16 aspects of the four noble truths in terms of Vajrayana, or in other words, tantra. First of all, tantra is a very complex and complicated topic. It has four classes of practice and, of these, the one that is relevant here is the highest class, anuttarayoga tantra.

As with sutra, tantra is a Mahayana vehicle of mind leading to enlightenment. What prevents enlightenment is the fact that the mind makes appearances of things existing solidly, encapsulated in plastic all by themselves, unrelated to anything else, as if there were lines around everything. That is what we really need to get rid of because, based on that, we believe the appearances correspond to reality, and then we act out as if things existed that way.

What makes that discordant appearance? This has to do with very subtle levels of the mind. We speak in the highest class of tantra of the subtlest level of mind, which is known as the clear light level of mind. This clear light level provides the continuity to our individual, subjective mental activity. Underlying all grosser levels of mental activity, it continues from moment to moment, through death into the next life. It continues in nirvana and enlightenment as well. It’s what provides the continuity.

This subtlest level of mental activity can be described in terms of a radio, where the radio can be on different channels, and it can have louder or softer volumes and so on. However, this clear light mind is just the level of the radio being on. The radio is on. It doesn’t matter what rebirth state, what station we are on. It doesn’t matter if it’s loud or soft, or how much suffering we have, the radio is always on. That is the clear light level of mind.

That clear light level of mind by itself, in its natural state, is very much what we are referring to when we speak about Buddha-nature. It doesn’t give rise to the appearances of solid existence. It doesn’t make things appear as solid and, of course, it doesn’t believe in them as corresponding to how things actually exist. It doesn’t have any concepts. It’s non-conceptual. In the dzogchen tradition, it is called “pure awareness,” rig-pa. This clear light level of mind doesn’t necessarily understand that these crazy appearances don’t refer to anything real. It doesn’t necessarily have any understanding of that. However, by itself, in its nature, it doesn’t make any of these discordant appearances.

What we want to do in tantra is the same thing as in sutra, we aim to eliminate forever true sufferings and its true origins. What are the true origins here? Remember, we briefly discussed the twelve links of dependent arising, and that we have karmic potentials left from our compulsive karmic behavior. Our craving after feelings and our grasping for an impossible “me” experiencing them activate some of these karmic potentials right before we die, giving rise to a throwing karmic impulse to throw our mental continuum into a next rebirth.

At the moment of our death, all we have is a clear light level of mind and a very subtle level of energy supporting it, like the electricity that powers the radio when it’s on. When the next rebirth state begins, this very subtle level of energy starts to become grosser, and our mental activity also starts to become coarser. The underlying clear light level remains, however. The radio is always on, but with a new rebirth state, it is now on a different channel than the one in our previous life. Again, with these coarser levels of mental activity, our mind starts making these crazy appearances again of solid existence. This is true suffering.

Obviously, what we want to do, as previously discussed, is to stop uncontrollably recurring rebirth and, in the case of tantra, stop the appearance-making of solid existence that takes place with rebirth. As in sutra, we need to have the non-conceptual cognition of there being no solid “me,” no impossible “soul,” giving rise to and experiencing these deceptive appearances. What we are aiming for is to be able to stop the grosser level of mental activity and activate that clear light mind and to do that in meditation and not just in death. We want to stabilize and maintain this clear light level of mind so that the mind doesn’t become coarser and start to make all these crazy appearances again and believe that they correspond to how things actually exist. For the clear light mind to do this requires that it cognizes the voidness of these appearances and of the “me” experiencing them.

In a sense, we could say that in tantra, true suffering is the appearance-making of solid existence and belief in these deceptive appearances that we have with rebirth. The true origin of that is the coarser levels of mind that give rise to them. These coarser levels of mind are tainted by the emotional and cognitive obscurations and these obscurations only occur on those levels. The true stopping is the clear light level of mind that is naturally free of making these appearances and believing in them. And the true pathway minds are, as with sutra, the discriminating awareness of voidness, but here accompanying not only renunciation and bodhichitta but also the various methods for stopping the coarser levels of mind.

In Vajrayana, then, we think more about this whole process of how the mind makes these crazy appearances. We want to stop the mind from making these appearances, and the most efficient method is to stop these grosser levels of mind is through the power of meditation.

What happens ordinarily is that our energies are going crazy through our body. We experience this by feeling nervous, insecure, upset and so on. To put it in a simple way, what we are aiming for in the advanced tantra practices is basically to centralize all that energy and dissolve it. When we do that, these grosser levels of mind also dissolve. When we are so worried and nervous, if we can calm down that energy, then the mind that is worrying and thinking about all these things will stop as well. There are very advanced yoga methods for centralizing, calming down and dissolving that energy.

We are talking about the pathways here to the true stopping of these energies coming out and getting grosser from the clear light mind level. We want to have all the understanding that we have been talking about with the clear light mind level because it is the most effective means for getting rid of the emotional and cognitive obscurations.

That is really the essence in brief of what we are trying to do in tantra. It is all based on the sutra understanding of the 16 aspects of the four noble truths and getting rid of the 16 wrong views. It’s not just about understanding their details, but it’s also about understanding the absence of an impossible “soul,” and impossible “me,” experiencing them.

Concluding Remarks

In working with these 16 aspects of the four noble truths it is very important to understand how cause and effect exists and how it works. A cause isn’t like some ping-pong ball, a piece of solid plastic over here, and the effect is another ping-pong ball over there. If cause and effect were like that, how could one bring about the other? What is connecting cause and effect? Is it like one of the Indian schools of philosophy that says there is a connector, something like a stick that connects them? Buddhism says that’s impossible. The only way that they can possibly connect with each other is if they are not these solid ping-pong balls.

Cause is a combination of a million things that are changing all the time, and the effect is also something that is made of million different parts that are changing all the time. It’s because of that that they can interact, and a cause can bring about an effect. If we think of the true origins incorrectly, that this ping-pong ball is the problem and this other ping-pong ball is the cause, making a big solid thing out of both, how could we ever get rid of them? How could a true pathway mind help us get rid of suffering and its causes? If we think of the pathway mind, we recognize that “This is the antidote. This is cessation. This is the result that I want to achieve.” However, if we make these into something solid, like ping-pong balls, sitting by themselves, we’ll never bring about true stoppings.

We really need to understand what these factors are, how they exist, and how each of us exists in relation to them. To do that, of course, we start with our ordinary level of mind. However, in tantra, we want to do that with the subtlest level of mind, that clear light mind, which we achieve in meditation through complicated yoga methods. We use these methods in order to really get the discriminating awareness of voidness strongly, non-conceptually, and most efficiently. That is what tantra is all about.